Полная версия

Полная версияEverything Begins In Childhood

“Do you recognize me?”

Observing the rules of honor, they didn’t start a big brawl. Sergey was the only one whose mug was smashed. Judging by everything, it was Vova who did it, the rest of them playing the role of jury. The jury was so authoritative that none of Sergey’s friends even moved an inch.

We also heard that Sergey, Big Visor, had apologized to Vova Oparin loudly in front of everyone. That was an integral part of Operation Retribution.

That guy never showed his face in our neighborhood again.

Chapter 44. “Dev Borin”

I woke up from a slight touch. It was Grandpa, who had just gotten up, covering me with the blanket up to my chin. Only he could adjust the heavy padded blanket with such ease. Oh, how warm and cozy it was under it in the predawn chill of this winter morning, especially on the side of the bed that retained Grandpa’s heat.

It wasn’t bad at all to sleep in the same bed with Grandpa, particularly in winter. When I was the first to get into bed, it would be cold, even somewhat damp. Shaking, I curled up into a ball, closed my eyes, trying to get warm, and thought, “I wish he would get into bed sooner. What is he dawdling over?” At last, the bed shook slightly – aha, Grandpa had sat on it. The bed began to rock – he got into it. And from that second on, blissful warmth began to envelop me as if it were coming from a well-heated stove, the only difference being that a stove cools off, and Grandpa never did. My body absorbed that warmth, relaxed, became soft and light… How great it felt!

I was surprised that such warmth didn’t accumulate in my body. I was also astonished that Grandpa would fall asleep as soon as his head touched the pillow, as if someone had turned him off. I tried to close my eyes and fall asleep, but it didn’t work. I think that Grandpa got very tired, especially in winter when he spent the whole day in his cold, unheated shoemaker’s booth.

That’s what I was thinking as I began to doze off, soaking blissfully in the aura of heat emitted by Grandpa. It was so good. And if Grandpa Yoskhaim didn’t snore, the night would be just splendid. That night was exactly that way, or perhaps I fell asleep so quickly that I didn’t hear Grandpa’s snoring. Now, after adjusting the blanket, Grandpa sat down on the edge of the bed and set about his morning routine – it would be more correct to call it a ritual.

He began it with a slow, sweetly resounding scratching, just the way he did it before bedtime. Then, came the delightful long yawning as Grandpa’s mouth stretched into an oval revealing two rows of white teeth, his beard dipping and beginning to tremble, as if informing other parts of the body that morning had arrived and they would soon need to start moving. Then, he squinted, joining his eyebrows together, slightly wiggled his neck, bent his head down and uttered a long, quiet, almost inaudible sound that resembled a moan. After that, he yawned and closed his mouth, but not for long. The next ritual was yawning accompanied by smoothing out his face. His mouth became an oval again. At the same time, he put his palms on his forehead, then slid them down his face and, after rubbing his cheeks, slowly lowered his hands. It seemed to me that a miracle happened every time he did it: Grandpa’s eyebrows straightened and became thicker. His eyes got bigger and sparkled. Even his wrinkles became less noticeable, another moment and they would disappear.

The last step was dedicated to the beard. Grandpa Yoskhaim held his beard in his hand and, still yawning, pulled it down. Perhaps, he was saying hello to his beard this way, or simply giving it the necessary shape.

After he finished with his beard, he began to dress. That ritual entertained me no less than the previous ones, especially during cold weather when, watching him, I thought, “It’s clear why Grandpa is as hot as a stove.”

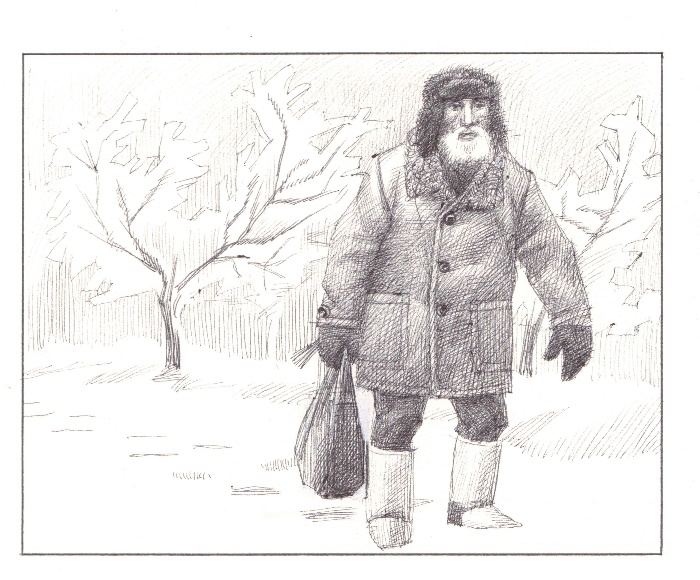

He shuffled his feet as he walked to the window, where there were two chairs. He sat down on one of them next to a pile of clothes on the other. He looked serious and concentrated as he picked up the padded pants from the chair and pulled them over his blue drawers. He also put on a warm long-sleeved shirt over a long-sleeved T-shirt. Then he stood up and tucked his T-shirt and shirt into his pants. After that, he tightened the string of the padded pants and pulled on over them another pair of pants, which was, naturally, a size larger than the ones he wore when it was warm. With all those clothes on, Grandpa should have looked like a head of cabbage. But no, he didn’t. He looked stocky but still well-built and quite handsome.

With the same serious air, without losing concentration for a second, Grandpa sat down on the chair and crossed his legs. Socks? Oh, no, no socks. Grandpa always wore boots, that’s why he wrapped his feet in a cloth. Grandpa wrapped the cloth around his feet, loop after loop, first around the heel, then the ankle. After the last loop, he had a neat white cocoon in front of him. It wasn’t easy to thrust it into a boot. Grandpa’s neck became taut, his face flushed… I tensed along with him. Oop! And the boot was on. Now, it was the other foot’s turn… Done. Grandpa was ready.

* * *Before going to work, Grandpa usually stopped at the storage room to pick up materials and tools. It wasn’t safe to store them at his street booth. I was dozing off a little when I heard the front door squeak: Grandpa had returned to the house for some reason. And then, Grandma Lisa’s voice squeaked much louder than the door:

“Oh my! Your boots are covered with snow! Stand on the mat! Don’t walk around! I, a sick person, will have to clean up after all of you… What do you need?”

Grandpa mumbled something in reply. He didn’t dare disobey Grandma. If he, God forbid, had stepped off the mat, she would have raised hell.

“Valery! Grandpa needs you! Hurry!” Grandma commanded.

I hurried to the hallway. Grandpa stood obediently at the front door. His cap with the earflaps was pulled down over his eyebrows, and he looked funny. His beard looked like a snowball stuck to his chin.

“There’s a bag near the storage room. I won’t be able to carry everything. Why don’t you and Yura bring it over before lunch time,” Grandpa asked without looking at Grandma Lisa.

A small puddle had accumulated on the mat. He arranged his bag, stepped outside, and the door squeaked again.

And again, Grandma Lisa’s voice squeaked louder than the door as she wrung out the wet mat:

“I, a sick person, have to clean up after all of you.”

* * *Back in the bedroom, I made myself comfortable by the window, that very window at which Grandma the scout often sat behind the tulle curtain. I looked at the delightful winter yard covered with snow. Grandpa Yoskhaim, the bag on his shoulder, approached the gate. His deep footprints stretched over the virgin snow across the entire yard. They branched off toward the outhouse near which Grandpa performed his usual morning washing, despite the cold weather. There weren’t any other footsteps in the yard but Grandpa’s. Even Jack didn’t get out of his house to see his old master off – it was too cold. Only a courageous sparrow had hopped a little in the vegetable garden. I could see the thin tracing of its footprints.

It was cold in the yard. The trees and bushes covered with snow had frozen into intricate sculptures. Now, it had fallen to Mother Nature the sculptor to create this unimaginable beauty. That morning, the snow was light and fluffy. Here it was, falling from one of the cherry trees, first from the top onto a branch, then onto another, then to a third until, suddenly, the whole tree was wrapped in a veil like a bride…

It was so quiet in the yard. Long bluish icicles hung from the ends of the gutters, which stuck out like tongues, protruding from under the roof. When it got warmer, they would begin their ringing song: drip-drip-drip… But now they were silent. It was too cold. And the grapevines were wrapped in a tarpaulin bound with wire.

* * *“Aren’t you going to have breakfast?” Grandma Lisa asked, entering the bedroom.

The question was asked without any good reason, to preserve convention: it was very early, and Grandma had not yet washed herself. Her hair, arranged in a small bun on the back of her head, now almost completely gray with a few red streaks, was neatly combed but not yet covered with a headscarf. That was why Grandma returned to the bedroom. She sat down on the bed. Her feet didn’t reach the floor, and her legs dangled in a funny way like those of a little girl. She arranged the headscarf and put it around her head. Then, groaning and rubbing her lower back, she went to the chest of drawers, to her father’s picture.

The Jewish religion doesn’t permit images of God. None can be found in synagogues or in people’s homes. Pious Jews pray with a prayer book in their hands. It was impossible to imagine that Grandma Lisa saw a sacred image in the photograph of the man she hardly knew, who, on top of that, had hurt her mother. Yet, hadn’t she turned him into a domestic idol, offering up prayers to him every day? But maybe, when she offered up prayers looking at the photograph, it seemed to her that she was also praying for her father to purify his sinful soul.

I don’t know… I was too young to ask Grandma about it. I only remember that it was somehow frightening to watch her pray. Her wrinkles looked deeper, her face was very pale and seemed to suffer in the dim morning light. Motionless, as if petrified with her frozen face, she looked like she was praying for the last time, hoping for God’s forgiveness and, after being forgiven, would collapse and breathe her last.

After she finished praying, she smoothed out the oilcloth on the chest of drawers, adjusted the photograph and, deep in her thoughts, said pensively:

“That’s life.”

She, of course, didn’t say that to me, but I decided to take advantage of the moment. The time after the morning prayer was practically the only time when Grandma softened. She might even open up about herself, her childhood. And I was very interested in that.

“Grandma, did anyone help you when you moved to Tashkent with Mama?”

“There were good people,” Grandma answered pensively, without looking at me. “There was Mama’s brother, a very kind man… May he be in the Kingdom of Heaven,” she raised her hands and looked upward. But I didn’t learn anything about her mama’s brother or how he helped Grandma’s family. No, I didn’t manage to draw her into conversation that day.

* * *Burdened by Grandpa’s bag with his shoemaking materials, Yura and I were marking time at the gate. Jack looked at us with interest, sticking his head out of his kennel. Grandma was on the porch and Aunt Valya in the door to her veranda.

“Walk together, next to each other,” she urged us.

How else could we possibly walk if we were to carry this heavy bag together?

“When you cross the street, look around!” Grandma Lisa shouted.

“Do you have enough small change? Have you checked?”

Grandpa’s booth was an hour away from home, near the Teachers Training Institute next to Out-Patient Clinic #16. We needed to take trolley number nine part of the way. That’s why they were reluctant to let us go by ourselves, but they didn’t want to contradict Grandpa.

“Let’s go, let’s go,” Yura stepped outside the gate and pulled the bag. “Let’s go or we won’t leave till night.”

And we began walking down the lane.

“Remember Sima?” Yura nodded toward the yard on the corner, across from the house where the old man and woman who had sold sunflower seeds had lived.

“She’s leaving for Israel. Have you heard about it?”

Absolutely all the boys were in love with fifteen-year-old Sima, including our cousin Akhun, nicknamed Baldy. But the slender beauty paid no attention to any of them; they simply didn’t exist for her.

“To Israel?” I asked in surprise. “Why would she go there?”

Perhaps that was the first time I heard about people leaving for other countries. If I had heard about it before, I hadn’t paid any attention to it. And here was Sima, a girl I knew.

“Why is she leaving?” I asked again.

“Why, why?” Yura shrugged his shoulders. “And not just her. My Grandpa Gavriel is also going to leave…”

Yura, as usual, was more informed than I. But neither he, who was nine, nor I, a twelve-year-old Soviet boy from Chirchik, could understand why people were leaving the Soviet Union, which was, in my opinion, the best country in the world.

* * *We followed the usual familiar route. Here was Shedovaya Street with its oak trees. The crowns of the giant trees met above us, except now they were covered with snow. That black-and-white arch, those mighty black columns on both sides, were so solemn that even Yura and I noticed it and fell silent. Somewhere up the alley ahead of us, at the end of the colonnade, cars and trolleys passed soundlessly, and here there was silence and peace, and an amazingly bright yet, at the same time, subdued daylight… Our oak alley was simply an enchanted kingdom.

But we managed to disenchant it.

Together we carried the bag with Grandpa’s stuff, but it was heavier for me since I was taller. Besides, Yura cheated – he barely lifted the strap on his side. When I noticed it, I lowered mine, and then Yura grumbled defiantly:

“Why don’t you hold it properly?”

“Do you hold it properly?” I snapped. “The whole load is on my side.”

“You’re taller. Is it my fault?”

“You can tiptoe,” I giggled. “It’s very good exercise.”

Yura immediately tripped me. I stumbled, almost fell down and, tossing the bag aside, attacked him.

We began to fight. The silent alley resounded with puffing and cries. First, we kicked and pounded each other, then snowballs came into use, then we ran into Grandpa’s open bag from which some of the contents had spilled out. Yura threw a rubber heel for a man’s shoe at me, followed by one for a woman’s shoe… and then it got out of control. Carried away by the fight, we completely forgot what we were using as projectiles and, pushing each other away from the bag, continued to throw, throw and throw.

We got tired, came to our senses, and, swearing at each other sluggishly, looked around.

The part of the alley where our battle had taken place looked like a wrecked shoemakers’ shop. Heels, soles, taps, pieces of leather were scattered here and there. A part of the space looked like an anti-tank zone: a sack with nails had ripped open, and they protruded from the snow, their sharp ends up.

Moaning and groaning, rubbing injured spots, we rushed to pick up Grandpa’s precious stuff. After lying in the wet snow, stomped by our feet, it didn’t look very good, to put it mildly. We were trying to place all the stuff into the bag, not helter-skelter. We were doing our best, but in vain. We couldn’t arrange everything the way Grandpa had it for we didn’t have his skillful hands. The soles and taps seemed to have doubled in number. They wouldn’t all fit into the bag, and we couldn’t close it. Wet, wrinkled pieces of leather, twisted insoles were sticking out of the bag in all directions.

We resumed our walk. Upset, looking fearfully at the bag, we reached the trolley stop. How could we explain to Grandpa what had happened?

“It’s very slippery. Get it?” It dawned on Yura. “You stumbled, and everything from the bag fell into the arik… along with you,” he added, casting his eyes over me.

The decision was made, the fight forgotten, and we were friends again.

Our trolley ride was all right, without further incident. Grandpa’s booth, nailed together from wooden boards, could already be seen near a tree. Grandpa sat on a chair halfway in the booth and halfway outside, a shoemaking claw between his knees. His legs were covered with a blanket that hung down to the ground.

As we drew closer, we heard the tapping of a hammer. Grandpa was attaching a heel to a man’s shoe. He raised his hand to his mouth to grab one of the nails he held between his teeth.

Grandpa wasn’t alone. There was a man in front of him who rocked now and then, as if repeating the movements of Grandpa’s hand holding the hammer.

“Just twenty kopecks? Well, ten,” we heard his hoarse voice as we came closer.

“Don’t be greedy! Give me some change,” and the man raised his hand threateningly as he swayed with great force.

Grandpa didn’t look at the drunk as he continued his hammering. Finally, he took the last nail out of his mouth, chuckled and raised his head:

“Aren’t you ashamed, asking money from a pensioner?” he asked without raising his voice as he resumed his hammering.

“What if he hit Grandpa?” I thought, but the drunk turned around and went away.

“What a foo-ool,” Grandpa said, hitting a nail. That was the word he usually used to end a conversation with a person who irritated him and behaved improperly. He pronounced that word distinctly and meticulously, drawing out the oo.

When the drunk heard those brief parting words, he stopped, waved his hands clumsily and flopped into the snowdrift. Yura and I laughed.

“Ah, here you are,” Grandpa noticed us. He smiled meekly as he continued tapping his hammer.

Grandpa didn’t like drunks, though he sometimes gave money to the most pathetic of them, out of mercy. But he couldn’t stand the impudent ones. And beggars who sometimes resorted to violence didn’t bother the old shoemaker with the gray beard. They had all heard about his personality and strength.

We were still holding the ill-fated bag in our hands.

* * *“Have you brought it?” Grandpa asked, without looking at the bag. “Thank you. Set it down. I’ll look at it later.”

Yura and I exchanged glances. He hadn’t noticed. Thank God, Grandpa was so busy. He put the hammer aside, took out the shoe knife with the wide blade and began to trim the rubber tap on the heel. That knife, a long strip of metal sharpened at an acute angle and wrapped in friction tape instead of a handle, seemed ugly and scary to me. But Grandpa handled it like a light butter knife. He placed a shoe onto his knee, holding it with his left hand as his right hand moved the knife quickly and easily. Excess pieces of rubber that looked like elegant strips from a deli slicing machine came off the heel. Just put them on toast and you would have a sandwich. Now I understood why Grandpa’s hands were so disfigured. Even though he was very adroit, the knife sometimes slipped off.

Then the grindstone began to turn, and the heel, after moving over it in a semicircle a few times, became perfectly smooth. The shoe was done. Grandpa wiped it with a piece of rag and put it on the shelf. And then an awl and thick thread appeared in his hands. Grandpa turned them above his head like a magician before doing a trick… Yes, his trick was worth showing to spectators. At least, Yura and I dropped our jaws watching how quickly and handsomely Grandpa’s disfigured hands mended the somewhat torn shoe tongue. The awl pricked the leather, raised the thread from underneath and pulled it out with a stitch. The edge of the thread was already in the stitch, the disfigured hands skillfully tied a small knot. Prick, stitch, knot… prick, stitch, knot… Before we realized, Grandpa had cut off the thread, turned the shoe in his hands, nodded and put it aside.

* * *We had heard many times how respectfully people talked about Grandpa Yoskhaim. He was not called a shoemaker, but Master of the Shoemaking Trade. Hardly anyone in Tashkent had been engaged in this trade for almost fifty years. All the residents of the area knew him. They called him either Bobo or by his first name, Yoskhaim-aka. The local authorities, in order to exempt Grandpa from high taxes, registered his booth as a small handicraft business. Even Soviet officials treated this independent person, who never lost his dignity, with respect.

* * *After Grandpa finished his work, he stretched, winced and rubbed his back.

“You’ll massage my back tonight,” he said, at last considering us worthy of a pleasant glance.

Yura and I nodded. We would never neglect Grandpa’s request, particularly after what we had seen today. How could he possibly work there on cold winter days from morning till night, with only his bottom inside the booth where there was a small electric heater? What if there were a snowstorm? Or a rain?

A man with a pair of shoes arrived. We said good-bye and went home.

* * *At about ten in the evening, after Grandpa had had supper and listened to the news, he went to the bedroom. While he was undressing, I went to bring Yura. Two young masseurs solemnly approached Grandpa’s bed. When he saw us, he began to turn onto his belly, groaning. Grandpa hated to display weakness. He never admitted he was ailing, and he only showed that he suffered pain when he had to change the position of his body.

After turning onto his belly, Grandpa ran his hand down the left side of his back and bottom.

“It’s here.”

“All right, we’re about to begin.”

The massage, it must be admitted, was unusual. Grandpa, perhaps, didn’t understand what risk he was taking when he ordered us to climb onto his back with our bare feet and shift from foot to foot on it. Only much later did I learn that experienced masseurs at Turkish bathhouses had been doing that type of massage since ancient times. I also learned about shiatsu, the Japanese massage done by experts, not with their feet but with their hands. They knew very well which spots should be pressed. What could Yura and I possibly know about all those subtleties? We just followed Grandpa’s instructions. Besides, we enjoyed it very much. It was a game and an honorary responsibility at the same time, and such a thing did not happen often.

Yura was the first to climb on top of Grandpa, and he stood a bit up from the spot which, as they used to say in olden times, was losing its noble contour. I followed Yura and climbed onto the left side of Grandpa’s bottom. Yura began walking slowly up the left side of his back, to the shoulders. He didn’t walk, he sneaked, he savored each step, alternately pressing his heel and his toe into Grandpa’s flesh. Then he made another round, and another one, and one more…

“That’s enough,” I said impatiently. “Enough! Let me do it!”

We traded roles.

Grandpa’s back seemed to be made of iron. I was heavier than Yura, the pressure was harder, but it was a springy hard surface under my feet. The bed was swaying slightly and sagging a bit, but Grandpa lay there as if two bits of fluff were rolling over his back. Of course, he could feel us walking around on his back. He felt it and was blissfully happy, encouraging us softly:

“Oh, how good that feels. Oh, well done. Oh, may you always be healthy and happy.” From time to time, he directed our efforts, “Yes, yes… Right there… One more time… Harder.”

Standing like a ballerina on my toes and steadying myself with my palms pressed against the wall, I pushed my toes into Grandpa’s back as hard as I could and shifted from foot to foot. And he didn’t even groan, he didn’t even pretend jokingly that it hurt. He just repeated:

“Oy, well done, well done.”

But even that was not enough for Grandpa. He had enjoyed the massage performed by us stomping on his back in turns, and then he commanded:

“And now – both of you together!”

Yura’s face expressed total delight. And now, the most interesting part was to begin.

Holding each other by the shoulders and crying out with pleasure, we performed something like a tribal dance on the body of a defeated enemy on Grandpa’s back. Apart from everything else, we enjoyed jumping on the back of old Grandpa Yoskhaim because usually we couldn’t even touch him with a finger. And here we did it with our feet.

But still we couldn’t forget, not even for a minute, that Grandpa’s back had been hit with a bullet under the left shoulder blade. That spot was very sensitive and had to be bypassed.

* * *“Why are you shouting? It’s night outside, time to be in bed.”

That was Grandma Lisa. With her hands on her hips, leaning against the doorframe, she looked at us and Grandpa, and her gaze was that of a person who was all too familiar with human weakness, delusions and ingenuities. And to make it clear to all of us, she exclaimed, raising her hands to the sky, “Dev borin!”