Полная версия

Полная версияEverything Begins In Childhood

“Two bowls, amak,” and he squatted near the shepherds.

I had to take a bowl in my hands.

“It’s delightful,” Father said after taking a sip. “It’s tasty, and it’s also medicinal. Pour more, amak.”

“Yes,” one of the elderly men said. “Of course, it’s a curative drink. It gives so much energy… Many people simply don’t know about it.”

I was surprised – looking at the babai dressed in ethnic attire, I would never have thought that his Russia would be so good. And Father joined in the conversation on this subject, which interested him.

“Yes, yes, I’ve been drinking kumis for only three weeks, and my blood test results are much better… I haven’t brought a jar. Please, give me a liter in yours. I’ll take it with me.”

* * *We were back home by eight. The clinking of dishes could be heard from the kitchen, and the aroma of something very tasty hung in the air.

“Well, congratulate her,” Father gave me the bouquet.

At that moment, Mama came out of the kitchen. As usual, she was wearing her housedress and apron.

“Oy! Is this for me?” Mama clapped her hands, took the bouquet and began examining the roses, repeating “And I couldn’t figure out where you had gone so early in the morning.”

It seemed to me she was very happy about the roses. It was an unusual treat for her. Father didn’t pamper her.

“Papesh, papesh!” Mama opened her arms and hugged Father. They kissed.

If I ever noticed any display of affection and respect in the relations between Mama and Papa, they emanated from her. He either didn’t know how to show it or didn’t want to. It was more likely both. So why was he so happy and tender on that day? Did he understand and feel something? Was he beginning to be proud of his wife?

Yes, he was proud, but not for her. His wife, the wife of Amnun Yuabov, had become the holder of the order. Everybody would read about it in the newspapers today. Practically the whole town would talk about Ester, and all the teachers at his school would certainly know about it. He would hear so many congratulations. His prestige would rise; he would partake of his wife’s fame.

I went to the living room. Emma was sitting on the couch with a red box in her hands.

“Look at the medal Mama’s been given. It’s s-o-o-o beau-ti-i-ful.”

I sat down next to her, and we began to examine the box closely. Red words shone on the beige silk lining: “Order of Labor Glory.” I read them to Emma. I also read what was below them, “For outstanding achievements in the field of labor”, and another long inscription, “By the Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet… Moscow.” Wow! Moscow! That’s how important our mama had become. The order was heavy, with its embossed image of a factory whose tall chimneys gave off smoke. The order was attached to a small bar with a safety pin on its back. I wanted Mama to pin it onto her dress as soon as possible.

We had seen quite a few medals and orders. We even collected badges ourselves. Holders of orders often visited our school for various meetings. And they often spoke on television. Honors were accorded to them. They were given flowers. Perhaps, we would soon see Mama on television, maybe even during a parade.

I imagined the city parade on November 7th or May 1st – our school always attended parades. There would be honored guests, important officials, the military, and other prominent people on the reviewing stand. And our mama would be among them. There would be flowers, flags, balloons, music – a brass band would be playing. And people would be marching past the reviewing stand, thousands of people! They would carry slogans and streamers – “Glory to Labor Heroes!” They would be laughing, singing, waving their hands. Emma and I would be floating in this human sea. We would also be shouting something, waving to her, to our mama. We would tell people proudly, “That’s our mama over there.” Obviously, I was also not immune to pride, even vanity, but mine, it seemed to me, was more unselfish that my father’s.

* * *The veranda was the coziest place in our apartment on warm autumn days. It was light, with wide windows and a wooden floor. Summer seemed to continue there even into the fall. And now, the veranda was filled with the aroma of apples, and with steam. Mama had been canning apple compote for winter since early morning. Yes, she had, instead of visiting friends and relatives to inform them about her achievement, to hear congratulations, to rejoice and be proud of it. Mama got busy with the chore she had already planned for this Sunday – home canning.

While Father and I were at the bazaar, Mama peeled and sliced apples. Now the apples were cooking in an enamel bucket in the kitchen, next to the veranda. Water was boiling in a large pot. Clean jars were placed near the stove. Washed with baking soda, they were impeccably clean. Mama transferred apples from the bucket into a one-liter jar just as quickly and skillfully as she worked at the sewing machine. Then she put the jar carefully into boiling water, took it out with metal forceps and carried it to the veranda where she twisted a lid onto it. Emma and I sat on the veranda enjoying Mama’s company, the cozy atmosphere, the general feeling of emotional comfort and peace in the house, and we asked Mama countless questions.

“Who brought it to you? Where did they get it? At a store?” Emma asked.

I pushed her, “Hold on. Don’t ask all kinds of nonsense. Mom, tell us how it happened. How did you learn about it?”

“Well, everybody got together at the factory…” Mama answered, chuckling, with a look of embarrassment.

“What do you mean ‘everybody got together’? What about the work?”

“Well, a break was announced…”

“A break? Because of you?”

All the humiliation, injustice, all the hypocrisy of the Soviet way of life, which I felt, learned about and understood later in life, did not erase those moments of pride and ecstasy from my memory – the factory took a break to congratulate my mama!

“Was another woman also given flowers?” I asked, because there were two women at Gucha who had been awarded orders.

Mama, who was closing a jar that stood on a chair, straightened up, rubbed her lower back – she had had radiculitis for a long time – and uttered:

“Ah…”

Mama was a person of few words, but I understood her language well. Her “ah” meant “when will you quiet down?” I was surprised – the conversation about the order seemed not to interest her in the least.

“You’d better help me close the jars. Do you want to try?”

Of course, I wanted to! Mama canned vegetables and fruits every autumn, and she did it so thoroughly that we couldn’t always finish the supplies of preserves, compotes, eggplant and squash “caviar,” and various types of pickles during the winter. So, we were not afraid of winter. Mama would also take part of our supplies to Grandma Abigai’s in Tashkent.

The last few years, Emma and I began to participate in the process, which seemed very absorbing to us, as long as we were spectators. But it turned out that it required skill, attention and patience, which we often lacked.

Mama gave me a device that I called a “twister.” It was a round metal thing that you had to put on a lid, press down and turn its handle at the same time. This “at the same time” didn’t come easily to me. Khirk! Khirk! the device grated when I pressed it to the lid, but when I began to turn the handle, for some reason, I couldn’t press down the lid at the same time. I became angry, I got tired. I couldn’t understand what we needed this device for. It would be easier to cover the rim of the jar with glue. It would hold firmly.

“Wait, wait, bachim,” Mama moved me aside. “That’s wrong…”

She pressed her left hand to the round cover of the device and turned the handle with her right hand. After one turn, she pursed her lips and pressed the cover harder. Then she made another turn, this time faster. The handle was harder to turn, the cover was harder to press down. At last, Mama straightened up and rubbed her lower back again.

“Well, this one shouldn’t pop this winter.”

Emma and I liked it when cans “popped.” Sometimes, during a winter night, the wind could be heard howling. And, suddenly, bang, as if a gun had gone off. Before I could get scared, I would realize that it had been a lid flying off a jar. And in the morning, I would hurry to the veranda, take a chair up to the shelves where canned vegetables and fruits were stored, and look for that jar. What was not on those shelves – cherry, apple and quince preserves, and many other things. It certainly wasn’t fun when a jar of vegetables or pickled grape leaves popped.

* * *“Ester, are you done with canning?”

That was Father out on the veranda. He had peered out at the veranda just about every minute, demonstrating increasing impatience. He wore a smart shirt and was clean shaven, a newspaper in his hands. He waved the newspaper and exclaimed:

“Just five people have been awarded orders in the whole town.”

“I’ve heard about it,” Mama said.

“Stop tinkering with these jars. Let’s go outside. You should let people see you.”

Mama winced.

“Should I? I haven’t cooked dinner yet.”

“I see…” Father coughed. “I’ll go for a walk. It’s so stuffy here because of your jars.”

He folded the newspaper neatly and left.

Mama raised her eyebrows, chuckled and began working on another jar. But soon we heard, “Ester! Where are you? Come to the window!” Mama went to the window. We ran along with her. Valentina Pavlovna was looking down from her balcony above us. Dora sat on the bench at the entrance surrounded by a group of tenants. Father could be seen not far from her, walking back and forth, holding the newspaper in his hand behind his back.

“Ester, congratulations!” Valentina Pavlovna shouted. “Congratulations, my dear! Well done! We’re proud of you.”

“Just look at her,” Dora said in a singsong voice. She had a mild Greek accent and pronounced every word very clearly.

“Not a peep comes out of you at home even when it would be good to make a fuss. And you’re quite a trooper at work. You really are something, after all.”

The people who stood around her laughed, and Dora stared at Father through the thick lenses of her glasses. Dora was a straightforward woman, and she couldn’t keep her thoughts to herself. She respected Mama, and she obviously had little liking for Father. Father pretended that he hadn’t heard anything, and he moved away a bit.

“Come join us!” Dora shouted. “We can’t hug you when you’re not here.”

Mama laughed. No, she didn’t just laugh, she burst out laughing loudly and happily. We didn’t hear such merry laughter often.

“Just a minute. I’ll change.”

She took off her apron and ran to the bedroom. Emma darted after her. In a few minutes, they both entered the hallway. Mama was wearing her favorite crêpe de Chine light-blue dress with a floral pattern, which was very becoming on her. I noticed that Mama had put on some lipstick, something she very rarely did.

As we were about to go outside, the door opened, and Father burst into the apartment. He must have come to escort Mama. He cast his eyes over her and exclaimed:

“What about the order? Where is it?”

“It’s here,” Mama pointed to Emma.

My sister beamed. The order was pinned to her short dress like a brooch.

“How… and you…” Father lost ability to speak and leaned against the doorframe.

“I can do without it.”

The earrings swayed slightly in her ears. It seemed to me that they were not just shimmering as usual but shining like phosphorus in the dark, charged by the sun for a day.

Chapter 43. The Officer’s Son

Winter arrived unexpectedly. It was very snowy. Standing at the entrance, we looked at the snowfall in shock. The sky messengers were fluffy, light and small, but there were billions of them, billions and billions, and they were flying and flying, falling and falling and covering everything around with a white carpet.

As I was looking at the snowflakes that flashed by my eyes, at that endless flow streaming from the sky, I was overwhelmed with a strange sensation. I felt as if I were seeing it for the first time in my life, as if someone had bewitched me, lulling me to sleep. Everything seemed so unusual and mysterious in that silent white swarm… Hey, who was rushing there from the kingdom of cold and darkness? It was she, the Snow Queen. There was her carriage rushing along… A white figure was seen moving in it… Her icy glance sparkled… She smiled, beckoning with her hand… Oh, no… I shook my head, and the Queen disappeared. And again, there were my friends, my street covered with snow. I caught snowflakes with my tongue. They melted right away, their cold touch barely felt.

Edem caught snowflakes in his palm and tried to study them.

“They say there are a hundred types of flakes, and each has its own shape,” he mumbled.

“Fat chance of seeing that, perhaps only under a microscope,” Kolya sighed.

At that very second, a snowball whistled by in the air and knocked off Kolya’s cap with earflaps. Vova Oparin was coming our way from the neighboring entrance.

“Cut the crap! Let’s go to the hill!” he commanded merrily.

The hill, our winter recreation place, was behind October Movie Theater, a five-minute walk from our buildings, which were at the foot of the hill, with the movie theater at the top. So, when we walked home from the bus stop, we went down the steps of that hill.

Now, to get there we walked up the hill. I took a sled, which glided smoothly on the snow that continued to fall. The sun looked like a dull disk through its shroud. The weather was great. Kir-rk, kir-rk creaked under our feet. “Fyu-to-too, fyu!” Vova Oparin whistled, walking with measured tread on the snow. We followed him, taking rapid, precise strides, like soldiers in formation.

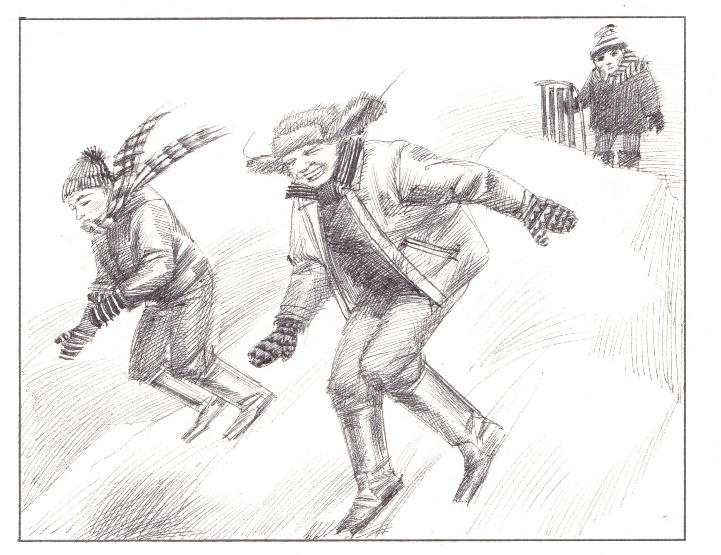

The hill welcomed us with squeals, laughter and shouts. It seemed that children from all over the neighborhood had gathered here. It couldn’t be a better day for sliding downhill whether on a sled, skates or just feet. Admirers of those types of sliding had pressed the surface of the hill smooth by the time we arrived. Boys, some on skates, others with just their kirza (rough leather) boots on, were sliding down those tracks. Those boots – I didn’t know whether they were really made of kirza – were our favorite winter footwear. Their soles glided on the ice just as well as skates; they also glided on well-trampled snow. Sliding downhill in them was quite an experience. Black and shiny with high tops, they were every boy’s dream. They were seldom delivered to stores, and parents weren’t too willing to buy them for their sons – it was dangerous footwear, and their sons could be expected to either fracture a leg or injure themselves in some other way on the hill at some point. Vova Oparin obviously wore kirza boots. I was lucky; thanks to a very snowy winter, Father had bought me a pair.

I gave my sled to some kids I knew. We went up to the movie theater and lined up at the top of the ice track.

It would be a big exaggeration to call the track even and comfortable for sliding. It was a natural track with lots of small dents, holes and knolls. Each of us got down the track any way he could. The most athletic and adroit of us organized contests – who could slide faster, more elegantly, with more intricate tricks. Each one demonstrated his claim at the start – a regular beginning of a slide after running at top speed.

Edem was the first to begin. He ran before sliding down, not too fast, for the first slide was a trial run. One needed to feel the icy surface, to make contact with it. It was your fault if you failed to do so and fell down. It meant you hadn’t reacted quickly, missed the right moment. That’s what happened to Edem. He stumbled on the steepest spot and rolled down head over heels. No one uttered a sarcastic remark nor even giggled. It was the first slide; it was excusable.

I was the second. I ran at top speed, touched the ice with my right foot, and my boots began to sing. I bent down, then squatted, trying to keep my balance. Now I was thrown up on uneven ice, now I skidded at turns. My feet were positioned at different levels, so my legs weren’t flexing simultaneously, and it was hard to control each of them in a different way at the same time. A hole… a knoll… another one… My left leg suddenly went up and my knee hit me hard in the chest, taking my breath away. I swayed but, spreading my arms wide, I managed to straighten up. Well done, arms. Thank you for helping me out. But at the end of the track I skidded again and began to spin. I thought I would fall down, but I didn’t, and I didn’t get snow in my mouth.

Only after I finished the slide did I feel how tense my legs were. I hadn’t exercised for a long time. It was all right; they would be back to normal soon.

Oparin approached the start and rushed down the hill.

Vova was a fearless person; he didn’t recognize trial slides. He made a long fast run, then a long jump that carried him to the icy track. He landed on the track with both feet. It seemed that he wasn’t sliding but flying like a projectile. Everybody on the hill stood still watching his run. Boys crowded at the top of the hill and stopped in their tracks. It grew quieter. Something like that was not often seen on our hill.

Vova bent down over holes, jumped high over knolls, and showed off, now spreading his legs, now drawing them up. His cheeks were flushed, vapor streamed from his mouth… Any girl would admire him.

Here he was at the end of the track. He squatted and spread his arms to begin his usual trick, a full turn while jumping. His feet left the ice… and at that moment, a snowball thrown from afar hit him in the face. That icy snowball hit Vova so hard that he fell down like a bird shot on the wing. He crumpled. It was clear that his fall was hard, that he had hurt himself badly. Edem and I rushed to help him onto his feet.

Vova’s cheek, nose, and upper lip, not just the spot where the snowball had hit him, but almost his whole face turned red and swollen. He didn’t groan or complain – that was not his nature – he just whispered very quietly, “Scoundrels.”

Now, we needed to find out who had played that mean trick.

It was clear that the snowball was thrown by a strong, skilled and experienced person. It couldn’t have been thrown by a child. We began to look around. The plotters didn’t even try to hide. A few guys roared with malicious laughter at the top of their lungs at the corner of the theater.

“Hey, you, show-off, how was the flop?” one of them yelled.

Just as we thought, the guys were much older than us; they were fifteen or sixteen years old. They were the kind people called “hippies,” with long greasy disheveled hair, dressed carelessly in unbuttoned jackets, shirts and bell-bottomed pants. That hippy style in clothes and behavior – familiarity, loud laughter, shouts coming from portable tape recorders in public places – had become very fashionable and was very persistent, despite the countermeasures taken by Party organizations, parents, school authorities and the mass media. Our group had not yet reached the hippy age, and we had a different mentality.

All of them were smoking, their hands in their pockets, and quite full of themselves in general. They weren’t from our neighborhood. We could see that right away. Guys from our neighborhood knew who not to mess with – Oparin, for example…

We grew timid as we saw our opponents. It would be dangerous to get involved with them. But Vova headed decisively toward the group, and we had no choice but to follow him.

Oparin walked as if he were on his way to a fight – he swaggered, his legs bowed like those of a horseman, and spread and raised his arms. He approached the guys and stood looking at them without saying a word. They looked as if they were ready to fight… And suddenly he said, almost merrily:

“You’ve got sharp eyes. Well done!”

“Prac-tice,” a guy wearing a cap with a big visor, who had thrown the ball, answered, after a pause. It was obvious that he was surprised by Vova’s friendliness.

And Oparin continued as if nothing had happened.

“Yes, you have no problem with moving targets. What are your results at a shooting gallery?”

“You should come see if you want to know.”

“Let’s do it. I’m Vova. And you?” Oparin held out his hand.

“Do you also want my address?” the guy chuckled scornfully, not holding out his hand.

Oparin swallowed the insult.

A mobile shooting gallery without wheels had been near the movie theater for two years. They agreed that the guy with the cap would compete with Oparin. Whoever lost would pay for shooting sessions for the winner’s group. We pushed, elbowing each other– we knew what Vova had in mind. How could we possibly not guess – Vova was famous for being a good shot in our school and all over the area.

“Do you have money?” Uncle Semyon, the shooting gallery attendant, asked without raising his head – he was reading a newspaper. We liked him. He was strict but kind, and he willingly played with us.

“I’ll pay for ten shots,” Big Visor said.

Oparin also put down his money.

There were five rifles on the metal counter. They were air rifles. You had to fold back the barrel and insert a small cartridge with a blunt end. Big Visor loaded a rifle, and Uncle Semyon set the targets going.

The forest clearing came to life: the door of the log hut opened, the woodcutter began to move his axe, hares and bears began flashing among the shrubs, the woodpecker began pecking… Big Visor aimed, the rifle “snorted,” and the woodpecker fell down… We exchanged alarmed glances – on the first shot… The satisfied guy reloaded the rifle and aimed at the woodcutter. A shot rang out, but the woodcutter kept moving his axe. Another shot, but the axe was still cutting.

“Sergey, don’t shoot without stopping. Stand still, then shoot,” a guy in a navy-blue sweater advised. Sergey mumbled something angrily and picked up another rifle. When he had taken ten shots, he had hit targets four times but hadn’t shot down a single moving target.

“Some shooting gallery,” he muttered contemptuously. “The rifles look like they were picked up at the dump. You should see the one we have in Troyitsky.”

Uncle Semyon was a very self-assured person.

“Do you know what a bad ballet dancer always complains about?” he asked calmly.

Our opponents’ mood turned bad. They only hoped that Vova, who was younger and had an injured face, would score fewer hits.

Oparin approached the counter, loaded all the rifles and pressed his elbow against the counter. He took time to aim… In a word, there was nothing new to say about it. He shot down all the targets one after another. He shot hares, bears, took the woodcutter’s life, and didn’t spare the lives of the birds.

We celebrated. We knew perfectly well how Vova Oparin could shoot, but to watch him, with the disgraced opponents around, was a true triumph. They didn’t expect anything like that, though they might have given it a thought when Oparin, knocked down by them, invited them in a friendly manner to visit the shooting gallery.

“Well, Sergey from Troyitsky, it’s time to pay,” Vova said amicably.

“Go to …” Big Visor began to say, but Uncle Semyon took a step in his direction. Sergey tossed a few coins on the counter and motioned to his friends, “Let’s get out of here.”

* * *On the way home, we had an animated discussion of what had happened. Only Vova was silent as he applied snow to his swollen cheek.

Vova Oparin was an officer’s son, and his brother attended the tank school. They didn’t forgive undeserved insults in such families. But what would the retribution be?

We found out a few days later. Someone from our class heard about what had happened from his friend who attended the school in Troyitsky. We also managed to get something out of Vova.

The operation was planned out down to the smallest detail. First, either Vova’s brother, a cadet, or one of his friends, went to Troyitsky. He found the school, as well as the corner where the school smokers usually convened. Vova, his brother and a couple of his classmates, robust cadets, went to Troyitsky on the designated day. They waited for the long recess when Sergey and his hippie pals came out. They approached them, first without Vova, asked for a smoke and chatted with them. And then young Oparin showed up.