Полная версия

Полная версияEverything Begins In Childhood

Two hours passed, and Boris and I grew bored with the ritual. Besides, when the mourners’ shouting got very loud, we were amused, but we couldn’t laugh, nor even smile, on such a sad day. They would notice it right away and say that we were heartless grandsons. Boris and I exchanged glances and got off the bench noiselessly.

We sneaked quietly, step by step, to the far end of the yard, to one of the storage rooms. There was the tandir, a clay stove which no one used any longer. There were a lot of old things scattered around that no one needed any more.

I liked that stove. It seemed to me to be a living creature. Every time I opened the door of the storage room, the tandir, when the daylight hit it, smiled at me merrily with its big round mouth, as if it was welcoming me.

Climb inside it, and you could get to the roof through its stovepipe. Even though the stovepipe wasn’t narrow, I felt somewhat ill at ease, uncomfortable, suffocating inside it. I would be covered with sweat, but I would overcome my fear, and, after getting to the roof, I was sure I would never be afraid to do it again… Alas, I was afraid every time I did it.

* * *“C’mon, c’mon!” That was Boris pushing me. He was climbing into the tandir behind me. I had already reached the stovepipe. Just a bit more, and I would be able to grab the bar, shaped like a cross, on the roof above the stovepipe… And there I froze.

That damned enclosure, the boards that surrounded the opening on the roof were all black inside from soot, and I had on a white shirt. How could I forget?

“What’s wrong?” Boris urged me. “C’mon!” Oh, well, I’d take my chances! I would try not to touch it.

I reached for the bar, and, suddenly, a sharp sting pierced my bottom. What was it? A bumblebee? I dashed upwards. Another sting! I yelled, dashed up again, forcing my way among the boards with my shoulders and elbows. As I hung there like a monkey, another sting – it dawned on me that it wasn’t a bumblebee. It was Boris! Boris, that damned traitor!

To confirm my guess, Boris’s loud laughter sounded, booming and sinister, from the tandir. The stomping of his feet was then heard – my cousin had played a cruel joke on me and had decided not to climb onto the roof.

So, there I sat on the slate roof in sorrowful meditation – what should I do? The shoulders of my shirt, the sleeves, the whole of it was covered in black streaks and spots. I wouldn’t be able to go back to the yard looking like that. Everyone would notice and ask, “What’s wrong with you? Where did you get covered in filth?” And if my father saw it…

But I had to climb down. I couldn’t sit there until everyone was gone. Besides, the boys could be heard yelling, puttering around in the clay, looking at something outside the gate near the arik. And Boris was already there, I could hear his voice.

My anger was dying down. I climbed out of the tandir, washed my hands in the neighboring storage room, shook my shirt energetically, which was useless, and sneaked sideways along the walls through the yard. On my way out, I managed to notice that more people had arrived, Grandpa Yoskhaim and Grandma Lisa among them. Here I was at the gate. I threw it open and dashed to the boys, calling to Boris. A piercing screech and the grinding of brakes were heard as an old Volga car stopped abruptly after lurching sharply, close to me. A pale, frightened man jumped out of it. “I almost ran you over,” he mumbled in Uzbek. And the fear on his face was immediately replaced with rage. “Are you crazy? Why don’t you watch where you’re going?!” he yelled loudly.

One could understand the man’s anger – another second, and I would have been lying under his car, badly injured and possibly killed. What would have become of him? But at that moment, I was incapable of thinking about it. I just couldn’t function or understand what had happened. My legs were shaky; I felt nauseous.

The man yelled, waved his hands, and there was already a crowd around us, mostly people from the yard. Someone was patting me on the head. It was Grandma Abigai.

“You must be frightened. It’s all right, it’s all right. Ah, that’s the last thing we need today. Aka Yoskhaim, take him to your place, please,” she asked Grandpa, who was nearby. “He’s so scared. I hope he won’t get sick. Let him pee, and wet his lips with urine,” Grandma remembered the old remedy to prevent a scare.

Obviously, that day was so sad that, no matter how hard I tried to make it easier for myself, it ended up in trouble.

Chapter 40. “Just Let Him Try It!”

“What do you go to school for?” Both parents and teachers ask this ridiculous question quite often, and always with a bitter intonation, or with indignation. You make noise in class – “What do you go to school for?” When you receive a D, come home with a reprimand on your report card, or with a black eye or torn pants – the same question…

Of course, we know perfectly well what kind of answer was expected from us. How could we possibly not know! And that’s particularly disgusting, because you had to lie.

To be honest, what boy, while at school, is capable of remembering all the time that he is there “to obtain knowledge,” as adults like to put it. To remember it all the time, one would have to be not a boy but some fictional character, some kind of a robot, or a model student. Such boys are not well liked by their classmates; they’re held in general contempt.

Only girls are forgiven for their diligence. Girls are a special case, though naturally, even they pretend. They find it more interesting to whisper to each other or exchange winks and messages with boys than to listen to a teacher and write down boring rules in notebooks.

Why am I remembering this? I’m remembering it because, for any student, the most wonderful time at school is the time when no one urges them to obtain knowledge, like, for example this time. The bell rang, five minutes passed, then ten, but our teacher still hadn’t shown up. In other words, our class’s head teacher, Flura Merziyevna, hadn’t yet appeared.

I would take full advantage of that golden opportunity, precisely because I had something very interesting to do.

Bending over a sheet of paper, I was deciphering a strange sentence that would have no meaning for an outsider: Kigoziini opab. This sentence made sense to me. Deciphered with the help of a secret code, it meant, “Valery, we have a hedgehog. When are you coming?”

Yura and I had been corresponding since the summer. We decided to encode our letters. You never knew who might read them in his home or mine. Our secrets were safe that way. Besides, when you added something to your parents’ letters or put a note into their envelope, you had to write long boring sentences, something like this, “Dear …, how is your health? How is the weather? Everything is all right with us. Wishing you the same.”

Coded letters liberate you from such nonsense. Parents are too lazy to ask what it all means. They just sneer condescendingly, “Are you playing some game again?”

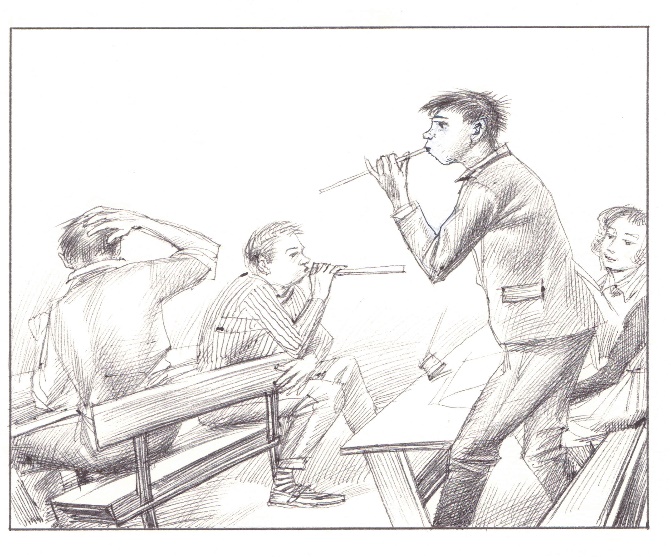

I tore a clean page out of my notebook and was just thinking about how to answer Yura when all ideas were knocked out of my mind by a strong flick to the back of my head. “Ouch!” I exclaimed, extracting a hard wad of chewed, wet blotting paper from my hair. I had been so engrossed in deciphering the note that I hadn’t noticed the beginning of a shootout. And it was in full swing.

It was possible to have a shootout without leaving one’s desk. That was the best thing about it. We could play it when a teacher was away, like today, or even when a teacher we weren’t afraid of was in the classroom.

Crackling, crunching and rustling were heard – notebook pages were turned into peashooters. That was the weapon, though the most avid fighters even had metal tubes. The smacking of wet lips was heard – each fighter was busy making a dozen or so “bullets” by chewing blotting or some other kind of paper.

The rules of the battle had been worked out long ago. The class was divided into two groups – the right row by the window exchanged shots with the left row along the wall near the door. The middle row could exchange shots with whomever they wished.

The battle tactics… well, there were no agreed-upon tactics.

Most of the shooters sat in the back of the classroom. The backs of the heads of those who sat up front were perfect targets. Poor things – they not only couldn’t shoot back, they couldn’t even shout “ouch,” as I had just done. But it hurt when a wad of blotting paper hit you on the back of the head. And our shooters were skillful. After inhaling deeply and pressing their lips around a tube, they spit a bullet through it with all their might. Phooey! And the air, like an exploding capsule, pushed the bullet rapidly out of the paper tube.

When there was no teacher in the classroom, the battle proceeded openly, like today. The noise was deafening, though it was somewhat strange. All that could be heard was phooey! phooey! If an outsider had walked down the hall, he would have stopped in astonishment, “What are they all doing in there? Are they spitting at each other from head to toe?”

A white hail covered the classroom, but the zeal of battle began to subside. Besides, some of us were burdened by worry – why was our Flura Merziyevna so late?

We could guess why.

An incident had taken place before this class, during the long recess, about which everybody knew. And some of us, including me, had been present when it happened.

But we didn’t want to think about anything unpleasant. As soon as I began to chew a new piece of blotting paper, Gaag, who stood at the door, shouted, “She’s here!”

The class grew silent.

After opening the door, Flura Merziyevna stopped. She had a pleasant face, round, kind and somewhat sad, and she didn’t smile. Sometimes, her face looked sadder, and we knew why – Flura Merziyevna’s husband, also a teacher, who taught drawing at our school, drank a lot.

Sometimes, when Bondarev would pass by in the hall during a recess, the stench of alcohol in the air was so strong that it seemed the wind had blown it in. Bondarev’s former nickname was “Little Hedgehog” because he shaved his head, but when his addiction to alcohol became known, his nickname was changed slightly to “Little Drunk Hedgehog.” Bondarev’s two sons, Alexei and Vladimir, were in our class and surely knew about the nickname, though no one said it when they were around.

The expression on Flura Merziyevna’s face was so sad, as if Little Drunk Hedgehog had gotten drunk today worse than ever before. She looked at us, sighed, and said quietly, “Those of you who were behind the school during the long recess, stand up.”

No one moved. My back strained, and my legs twitched slightly, but the “law of the pack” that kept others on their seats, held me in place. We had to procrastinate as long as we could.

The long recess. How well it had begun when Zhenya Andreyev and I ran out into the school yard.

It was late autumn. There were neither flowers nor little musicians in the yard. The wind blew along the paths, arranging the rustling yellow-red leaves into piles. Then it swirled and swirled them, as if in an endless dance, carrying them from one end of the yard to the other.

Yes, the weather had turned bad, but we didn’t complain. High school students even preferred inclement weather, of course, with the exception of torrential rain. When the weather was bad, they could hang around behind the school without being bothered – not a single teacher would venture into that part of the school during recess.

Comparing a long recess with a time-out between the two halves of a hard and tense game, one could imagine the teachers putting their heads together, discussing the next tactics they would use to counter the intrigues of their disobedient, lackadaisical students.

Teachers were the last thing those very lackadaisical students cared about now. It was their time to relax. That’s why they had to hide in a secluded corner behind the school.

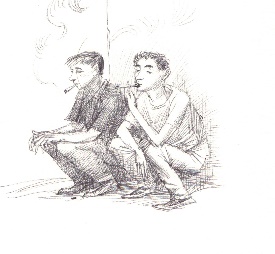

Bychok means “cigarette butt.” One could often pick them up in places where men would get together, say, at a beer stand. Sometimes, kids would steal them, or even whole cigarettes, from their fathers. Quite a few bychoks could be found behind the school, where high school students in the upper grades smoked their own cigarettes during recess.

Today, the smokers had great luck. A day before, there had been a volleyball game between our team and one from a neighboring school in our school’s sports hall. After the game was over, the players had smoked to their hearts’ content outside. That was clear from the number of cigarette butts. On top of that, the choice was better than at any cigarette kiosk. Not only were there Prima, Belomorcanal, and the local Golubeye Cupola (Blue Cupolas) cigarette butts without filters, but even foreign made BT butts on the ground. It was clear that there were some well-off guys among the players.

I avoided the gatherings behind the school because I didn’t smoke, and I didn’t feel I belonged there. Zhenya was a different story; he did whatever he wanted. On our way to the pavilion, we had to pass the bychkovists, and suddenly Zhenya stopped.

“Wait. We should ask Petya whether he’ll bring a ball tomorrow.”

Petya Bogatov, our classmate, an excellent soccer player and the owner of a real soccer ball, was also a smoker. Apart from him, three of our other classmates – Bulgakov, Zhiltsov and Timershayev – were there, hanging out with the seniors.

While Zhenya and Petya talked about the ball we needed for the next day’s game, some boys picked up bychoks and were getting ready to enjoy them.

I stood near Sergey Bulgakov and watched him wrap a piece of thin wire covered in blue insulation tape around a cigarette butt accurately and skillfully. It was a necessary precaution; otherwise his fingers would smell of tobacco. Everybody did it.

Then Bulgakov struck a match, but he didn’t begin to smoke. First, he held the flame against the filter. Heaven knows who had smoked that cigarette. And only after that did Sergey half-close his eyes and pull at the cigarette butt. The way he stylishly held his cigarette butt on the wire handle was a sight to see.

Everyone was already smoking, some of them leaning against the wall, others either squatting or walking back and forth, joining small groups involved in lively conversations.

Our classmate, Vitya Shalgin, approached one of the groups. Timur Timershayev immediately took a step in his direction. He threw out the unfinished cigarette butt, moved closer to Vitya and said:

“Haven’t I told you to stay away from Irena?”

His voice was so hoarse and low that it seemed to me the smoke was pouring out of his mouth from rage, not because he had smoked.

Vitya mumbled something in response. I couldn’t hear it even though I was standing nearby. But Timur, obviously, didn’t care about his reply. He drew his arm back and punched Vitya in the face. It was a very hard blow, for blood gushed from his shattered mouth. Vitya cried out, staggered and crouched.

Timur was generally a quiet guy. I don’t remember him ever losing his temper. He never attacked anyone, even though he was very strong. But, all of a sudden, he did.

It grew noisy. A few boys dashed to Timur, who was still standing over Vitya, his stance threatening, to pull him away. Timur tried to break away, yelling:

“Get out of here! Just let him try to walk her home again!”

After pushing the boys back, Vasily Lumis, also our classmate, went over to Timur. I hadn’t noticed him appear, but it was good that he had.

Vasily Lumis was Greek, so perhaps he had inherited strength, decisiveness and fairness from his ancient ancestors, from some Hercules. Vasily took Timur by the head in his ample hand, folded his other into a fist, shook it in front of Timur’s face and said:

“You either be quiet or I’ll knock off your schnozz.”

“Schnozz,” or nose, was the favorite word of our school Hercules.

Timershayev calmed down right away. He knew, as did everyone else, that Vasily never repeated anything twice.

Now, everybody surrounded Shalgin. He was still sitting, very pale, blood dripping from his injured mouth.

“His whole lip is split. The wound’s very deep,” the boys were saying. “Are his teeth intact? We should take him to the teachers’ room, quick!”

Taking Vitya to the teachers’ room would mean confessing that we had been behind the school and witnessed the brawl, in other words, being subjected to interrogation. Helping him would mean revealing oneself, and others. “Can you get there by yourself?”

Shalgin nodded and, holding his head up, trudged along to the teachers’ room. At that moment, the bell rang, and we ran to our class.

* * *That was what had happened before class. That was why Flura Merziyevna was late and entered the classroom with such a sad face. It was clear from her first words that Vitya Shalgin had “fessed up.”

Everyone who had been behind the school hoped in vain for a miracle. After not obtaining any confessions from us, Flura Merziyevna sighed again and began calling names. Timershayev was first. He stood up, clattering the seat of his desk. He looked gloomy, and it seemed he was about to repeat, “Just let him try it again!”

Irena Umerova, the culprit in this scandal, primped like a queen. She sat, tossing her white bows about, obviously happy and proud that the boys had fought over her. The rest of the girls stole envious glances at Irena. Just imagine – she was the first girl in our otherwise friendly class to have been the cause of a fight. Ah, girls, girls…

We plodded along in single file to the teachers’ room on the second floor. “Handling room-meddling room,” that’s what we called those unpleasant premises, because we were summoned there for only one reason – to be nagged at, set straight and the like. We had many graphic expressions for the subject, and we were about to experience them all.

The white gowns of ambulance attendants could be seen in the far corner of the teachers’ room. Vitya’s bandaged head was visible among them. He was to be taken to the hospital for stitches. Now, hardly anyone felt sorry for Vitya – he had betrayed us.

Inna Nazarovna Bass, the academic director, was at her desk near the window. She was the one we couldn’t stand. It was she who summoned us to the teachers’ room to set us straight more often than anyone else. And she would set us straight so hard that we thought she should have been a jailer rather than the academic director. Even her appearance evoked our loathing. Her small black curls protruded over her forehead like a bed of cauliflower turned black. She used her long, manicured nails to pick at her teeth, and she would scratch her calves, sticking her hands into the top of her smart black boots. Inna Nazarovna thought she was irresistible, and she dressed as stylishly as her means and understanding of what chic was permitted.

Now, she sat with her legs crossed, her small round predatory eyes scrutinizing those standing at the door.

“Well… Bulgakov is here, naturally… You practically live in the teachers’ room. Are you trying to get expelled from school soon? Perhaps it’s time to do it, along with Zhiltsov, for company. And you, Timershayev, have you decided to go straight from school to the courtroom? To a jail for juvenile delinquents? Imagine how happy your parents will be! Do they teach you to behave that way at home? I’ll have to ask your parents. But first, you’ll tell us how you have reached the point where you could do something like this. Do you understand that you nearly killed Shalgin?

Inna Nazarovna moved forward, fixing her eyes on Timershayev. Timur was silent. He didn’t look at Inna Nazarovna so her piercing gaze didn’t affect him.

He had that same expression on his glum face: “Just let him try it again!”

“Timershayev, are you deaf?”

Timershayev was silent.

“All right. We’ll find out why it happened. And we’ll find out what gatherings take place behind the school. Got it? And if any of you are seen there again… Andreyev, Yuabov, this applies to you too. Since when have you joined those who disgrace our school? And, in general, this class is clearly getting worse.”

Then, Inna Nazarovna at last turned away from Timur, stood up and, putting her hands behind her back, walked around the room. She stopped in front of Flura Merziyevna, stared at her and said slowly:

“This class is clearly getting worse, Flura Merziyevna.”

We were allowed to leave after being given one last stern warning. Flura Merziyevna stayed in the teachers’ room. It was clear that now it was her turn to be straightened out. I’ll bet she would rather have left along with us.

Chapter 41. How the Bottle Was Buried

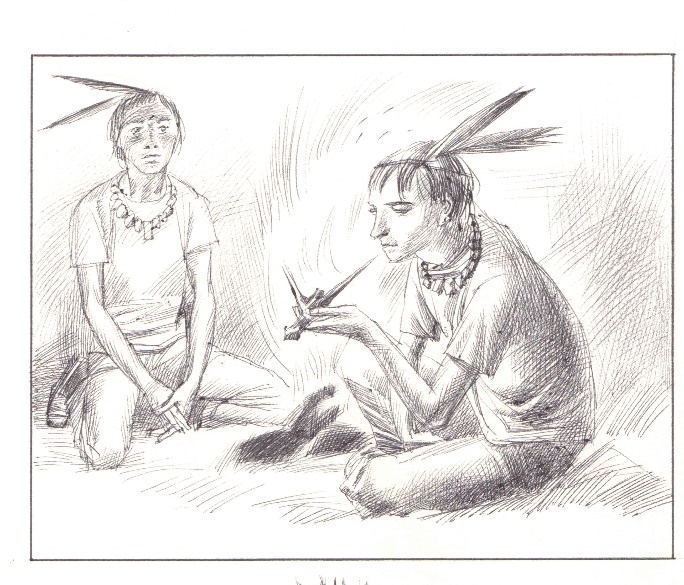

“Does everybody agree?” Chingachgook asked.

His face, illuminated by the fire, was serious and undisturbed, just like the face of a real Indian under any circumstances.

His thick hair, light and amazingly straight, covered his high forehead down to his eyelashes, just like a real Indian’s. However, as we all knew, Great Snake had only one strand of hair crowned with a feather on his shaved head.

Rustem Angherov, Flura Merziyevna’s younger brother, couldn’t walk around bald. It was all right, for even with his hairstyle, he was the best Chingachgook among us.

“Does everybody agree?” he asked.

“Ugh!” came the booming response, and five clenched fists were raised above our heads.

Chingachgook cast his eyes over us and nodded.

“The council of elders has approved the decision.”

That very important event took place in the vegetable gardens near the back wall of Building #16 in the evening. The Sagamores, the elders of the Delaware and Mohican tribes, united against the Iroquois tribes, who feuded with them.

However, it had certainly not happened in the vegetable beds near our building, nor in the town of Chirchik, but in a thick forest on the banks of the Hudson River. It happened by a big hot fire, with a whole log burning in it, and not near a burning piece of plexiglass. And they passed the peace pipe around from hand to hand, as expected, not a twig torn off the hedge.

How fortunate we are that nature endows us with powerful imaginations in childhood, which allow us to enter virtual reality, as the expression goes nowadays. To put it a simpler way, it allows us to go where we want and become whoever we want the moment our imagination is fueled.

Of course, we understood that we were playing Indians.

If only my imagination were half as powerful now.

I knew it was just a piece of plexiglass buried in the ground that was burning in front of me, but I admired the way it melted slowly, the hundreds of tiny bubbles sizzling on its surface, disappearing, reappearing, disappearing again, consumed by the flame. But somehow, I also saw a dry oak log with black charred bark instead of plexiglass and the tongues of flame above the hole in which the fire had been built. It was quiet in the forest, only dry leaves rustling in the wind. And we strained our ears to hear twigs that might crack as enemies crept through the trees. And you could hear, yet at the same time not hear the voice of Dora, who was nagging someone at her place. I didn’t know how all that happened. Very few adults had the ability to transform themselves, with the exception of actors.

* * *Could I possibly have imagined at that time that in about thirty years I would find myself in the actual places we boys had “visited” while playing, that I would stand on a wooded shore of Lake Ontario, one of the five Great Lakes, not alone but with my children, Daniel and Victoria, American by birth? And I was glad that that faraway evening and the plexiglass fire remained in my memory…

* * *The fire burned out. It was time for us to go home. So, simply and naturally – only children could do that – we became Rustem, Vitya, Zhenya, Igor, and Valery instead of Indians. However, our thoughts were still with the heroes of our favorite book.