Полная версия

Полная версияEverything Begins In Childhood

Every time I visited my grandparents, I compared their poor, almost rural, abode with our Chirchik apartment with all modern conveniences – hot water, a bathroom, and gas that no one thought about conserving. Here, the house was small; it had a living room and one bedroom, where the daughters slept. Now that Grandpa Hanan was very ill, Grandma slept with them. There were two summer rooms in a separate house in the yard, but it was too expensive to heat them in winter.

“Valery, Valery,” Grandma smiled at me and nodded her head. “Get the tea dishes.”

Grandma came to the kitchen fully outfitted in a sheepskin vest, felt boots and a headscarf.

Grandma always wore a headscarf, replacing it with a lighter one at night. Grandma, by the way, adhered strictly to all Jewish customs, not just the ones regarding clothing.

But she applied those strict rules only to herself; she didn’t extend them to the whole family. She wasn’t angry if someone mixed the dishes or accidentally turned on the light or gas on Saturday. Grandma Lisa would screech furiously in similar instances. Grandma Abigai almost never raised her voice, well, sometimes at the children, but never at Grandpa Hanan.

Many children watch grown-ups’ relations closely. They compare them, denounce them or approve of them. I had serious reasons to do that. I lived under constant strain while awaiting the rows kicked up now and then by Father at our home. I heard squabbles between Grandma Lisa and my father or between her and Grandpa almost every day at Grandpa Yoskhaim’s house. In a word, I had seen enough family squabbles. I certainly felt that they weren’t good. Grandma Abigai, Grandpa Hanan and their children served as corroboration of this feeling. Theirs was the place where I never heard squabbles or rude and endless mutual nagging. Certainly, Hanan and Abigai had their differences, and she had occasions to be dissatisfied with her husband and children, but differences were cleared up in a normal way, not without stress but without malice and insults. In their house, one could feel that they loved each other, that they shared all the difficulties, and they had many…

When I grew up and learned more about them, I thought with bitter bewilderment – why had such a nice family had so many misfortunes? It wasn’t fair.

Let’s take Grandpa. He was a good, kind, fair person, and a loving husband and father, but fate inflicted blow after blow on him.

* * *Grandpa grew up in an Orthodox Jewish family that dreamed about the homeland of their ancestors. In 1933, his mother, Bulor, escaped from the Soviet Union with her fourteen-year-old daughter. I don’t know why her son couldn’t have escaped with them, but I knew that he had tried to do it twice before getting married in 1934 and been caught both times. Thank God, the laws in the USSR were not yet that fierce, and his punishment was limited to imprisonment. My Great-Grandmother Bulor, after long ordeals in Afghanistan and Iran, made it to Israel in 1962, and she sent an invitation to her son. But Grandma Abigai didn’t want to go there, so they stayed in Tashkent. He returned home after the war with asthma. Then he contracted tuberculosis. He needed to feed his big family. But how? Hanan had a pension, or whatever it was called, as a discharged war veteran, but it was too little to live on. And he, like many men in those years, got involved in a not-very-honest trade. What they did was subject to criminal charges. Someone from Grandpa’s group would steal leather at a factory; then it would be resold. They had points of sale where they had “their own people.”

Seven people were involved in those operations. One of them was caught, and he reported them all. The whole group was arrested and prosecuted, and all but Grampa cracked during the trial. Grampa behaved with dignity, even though he knew he would be given a longer sentence.

Now, thinking about Grandpa Hanan’s life, I understand that such operations and dealings were not for him. He wasn’t greedy or cunning. He wasn’t adroit in a mundane way. He was definitely a decent person who felt indebted to the people he considered his comrades. That’s why he didn’t testify against them. Could this person who loved music more than anything in the world become a deft swindler? I could more easily imagine Grandpa dancing and singing in our yard, “E-este-er, I’m here!” than carrying rolls of stolen leather to a dealer.

Hanan spent two years in prison. Then Avner got him released. But Hanan’s tuberculosis had gotten much worse in the stuffy prison cell. It was very difficult for him to work after his release. My childhood memories of Grandpa the Grinder were just a vivid picture impressed on a child’s memory. It was too hard for Hanan to make the rounds of the city with a very heavy grinding machine on his back, so he soon gave up that work. I don’t know how he earned a living. I only remember that he was always up and going, trying to “do deals” until the end of his days. Only he didn’t have any luck in this harsh world. He had neither education nor a real profession. He couldn’t even manage to build a more spacious, warmer house.

That winter morning, as I sat at the window mumbling the lines of Lermontov’s poem and listening to Grandpa’s breathing, I already knew that he had tuberculosis and that it was in its final stage. Neither I nor the adults understood that the terrible disease was dangerous for those around him. Even if they had understood, they couldn’t have done much. He had his separate dishes, but it was impossible to quarantine him.

Haggard, with hollow cheeks and sharp shoulders, he lay in his bed in the living room – he could no longer get up. He had a hacking cough, was wheezing, moaning, and coughing up phlegm into a small jar in which clots of blood floated in greenish-yellow phlegm.

As I entered the living room from the kitchen, Rosa, Mama’s sister, was picking up the jar from the floor.

She had just emerged from the bedroom, bright as the flower she had been named after, a bright scarf around her head, wearing a colorful baize bathrobe and multicolored slippers. Seeing me with the teapot near the stove blazing with heat, Rosa smiled and said melodiously, snapping her fingers, “Tha-at’s my bo-oy, tha-at’s my bo-oy.”

A kind word and a joyful smile – that was our Rosa. She walked, dancing slightly as if to the rhythm of one of her favorite Uzbek tunes.

It seemed to me that Rosa was uncapable of getting angry. When she wanted to reprimand me or Emma, she knitted her brows and waved her hands, but almost immediately, her lips formed a nice grimace, as if she were not going to reprimand us but, on the contrary, to apologize. Her gold tooth – it was considered a must in Central Asia for every person to have some gold in their mouth – glistened like a ray of sunlight, and we understood that we had been forgiven.

Rosa didn’t know how to get angry. We felt and were well aware of how much she loved us. When she talked to Emma, the expression on her face changed; it looked kinder, and she knew how to find special words. “Emma, are you up or are you down?” she would ask when she worried that Emma was tired or upset. That was the agreed-upon signal – “Are you in a bad way? Tell me, and I’ll help you… I’m here for you.”

Yes, my aunt was kind and merry, a smile quite often spread across her face. It was clear that she took every opportunity to enjoy herself with all her being, as if all life did was pamper her and put her in a happy frame of mind.

But that was not the case.

Rosa had had epilepsy since she was a child. I never saw her during seizures, but I heard about them. In those days, epileptic seizures were considered something terrible, appalling, shameful – unconsciousness, cramps, foam on the lips – at least among the Bucharan Jews. So, I thought that if they concealed it, it meant that they had to. But I was not in the least afraid of Rosa. I pitied her, and I loved her.

My relatives didn’t have any understanding of medicine. They thought that Rosa had grown ill because she had experienced a violent fright. When she was a little girl, she got lost on the way home from a store, and she wandered around in the dark for a long time. She wasn’t found until it was very late.

Her fright, naturally, had nothing to do with it. Epilepsy sometimes begins with a serious injury to the head but is more often congenital. They haven’t yet learned to cure it, but seizures can be prevented with good medication.

I don’t know where and how Rosa underwent treatment, what medications she took, or how often she had seizures. It was never discussed in this family. But they did grieve about it very much.

I saw how Grandma Abigai stole glances at Rosa, how she cried and talked to my mama in whispers when they had an opportunity to get together. Grandma thought that Rosa hadn’t gotten married because of her disease, and she was about thirty. It meant that she would not have children. That was a great misfortune in a Jewish family.

But it wasn’t just Rosa who upset her old parents.

They had five children – four daughters and a son. It was hard to imagine how Grandma raised them all by herself during the war years.

The children grew up, but there were still many worries. Out of their five children, only the two older ones, Marusya and Avner, lived more or less all right. They had their own families, and they didn’t live in poverty. I don’t mention my mama among those who lived all right for I knew how hard her life was.

Avner inherited his emotional qualities from his father, though he was more resolute and businesslike. He managed to get an education. I will write in more detail about my favorite uncle later. Aunt Marusya got married and, a few years later, along with her husband Kolya and two children, moved to Bukhara, her husband’s hometown. They had two more children there, so she was busy up to her eyeballs, and I saw my aunt only when she visited her relatives.

I loved those visits. Even though Marusya lived far away, she was a person very close to my heart. Every time she visited, and it happened twice a year, it seemed to me that we had seen each other just a few days before. Aunt Marusya was kind and merry, just like her sisters. She had a habit, or rather emotional need, to greet Emma and me with a song. It started when we were very little, and it continued that way. As she sang, Marusya danced, accompanying herself with her fingers. She didn’t clap her hands as others usually did. She pressed her left fist into the palm of her right hand and tapped on the spots between the joints with the tips of her fingers. I was surprised at how loud it sounded. I tried many times to do it but could never make a sound.

And the smile she greeted us with, and not just us, radiated such kindness that one could only call it boundless, but Rosa’s face also lit up with a smile when she saw us. She also danced and sang. And now, as I write about it, I don’t see much difference between them. Actually, the way they looked, their manners and movements were full of distinctive qualities.

Aunt Marusya seemed to me to be the embodiment of tenderness. Every time she stood beside me, with her feet slightly apart, as if she wanted to be steadier, with her round face and jet-black hair, tall and solidly built, I felt calm, warm and protected, almost like when I was near Mama.

Rena was the youngest in the family. During those winter days when I visited my grandparents, she still lived with them, and she caused them much distress.

When they talked about Rena in the family, they said she was somewhat strange. Rena was carefree beyond belief, as a child. When she grew up, she still behaved like a child. She couldn’t be relied on for anything. When she went to a store for a minute, she could disappear for the whole day. Where was she? What did she do? Nothing. She just loitered around stores and the bazaar.

Rena didn’t go to college. She didn’t have any profession. Every time she began working somewhere, she very soon gave it up. When she earned some money, she spent it to buy something trivial, as if she didn’t understand the difficulties the family was experiencing.

Obviously, she didn’t understand. Even Emma and I noticed it, and we made fun of the way Rena answered Grandma when the latter asked her for help.

“Rena,” Grandma would begin, “why don’t you wash some dishes.”

Before Rena could open her mouth, Emma and I would yell together in her place.

“Holle! Byad!” which meant “It can wait! It’s not urgent!”

Despite all her peculiarities, which kept Grandma angry and grieving, Rena inherited the family kindness. She and I were fond of each other.

I remember a scene from my early childhood, maybe even my infancy. I lay in a wicker basket lined with blankets. I was laughing loudly and stroking my bare legs with my hands. And Rena, squatting by the basket, was tickling me, pinching my cheeks lightly, and crying out joyfully, “Oy! Oy!”

I was very amused and happy.

* * *Years would pass, and Rosa and Rena would get married. They would experience joys and troubles. They would have their own children. Rosa would also adopt children. Grandma Abigai needn’t have worried. But that would be later.

During the days I am writing about, both sisters lived at home. Rosa was the only person my grandparents could rely on. When she returned home from the factory, no matter how tired she was, she would begin doing chores right away – cooking, cleaning, attending to her father.

And now, after washing that terrible jar, which I was even afraid to look at, she fussed around Grandpa Hanan, speaking to him softly. She adjusted his bed and called to me, “Pour some hot tea for us.”

I had already poured tea into Grandpa’s bowl and carried it, trying not to spill. For those who have asthma, tea is better than any medication. Of course, I knew that because my father had asthma.

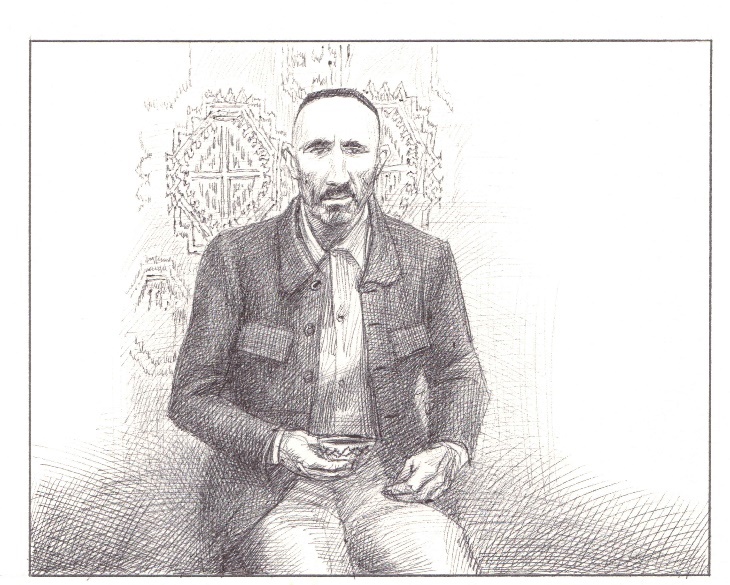

Rosa bent over Grandpa – he sat on the bed pressing his palms against the bowl – and raised it carefully to his lips. Grandpa looked at me, smiling tenderly. His smile was very meek, hardly noticeable. He patted his bed with a hand, inviting me to sit down. His eyes came alive; they even began to shine as before. And they were telling me, “I’m so glad to see you. I love you. Joni bobo.”

I loved Grandpa Yoskhaim no less than Grandpa Hanan. I’d grown up in his house, but still, my feeling for Grandpa Hanan was different: it was special. I never called him Grandfather, only Grandpa. I would never pull him by the beard. I would never play any tricks on him like the ones Yura and I devised in the old yard.

One could say that I felt more respect for him. But for some reason I don’t want to use that word – it seems somewhat cold.

Did I, perhaps, feel more pity, more pain for him?

Chapter 39. Parting with Grandpa Hanan

It sometimes seems to me that memory is like a sack of old things stuffed into a storage room or the corner of a closet. When you want to find something, you begin to rummage in the sack, pulling out one thing after another. And as you do it, you remember everything related to these things, and you feel pain somewhere in your chest. And you remember everything that was dear to you. The longer you look at an old thing, the longer you hold it in your hands – be it a dress, worn shoes or a small broken box – the more you remember people’s faces, colors, sounds, even smells. And those are not just snatches of reminiscences that drift before you but whole scenes from the past that had seemed forgotten and hidden at the bottom of the sack. All you need to do is take it out of the closet and rummage around in it.

* * *It’s cold in the house this morning. I put on Mama’s warm cardigan, throw her favorite red scarf on top of it, and put on the skull cap, a present from Muhitdin, the doctor from Namangan who fought so long to save Mama’s life. Dressed like that, I sit down at my desk to work in the blue pre-dawn expanse of a cold October morning, and I hear Mama’s voice, “Get up, son, get up…”

Why today? Mama’s scarf… early in the morning, just as in the old days when Mama’s tender voice would wake me up… or at an even earlier pre-dawn hour, just like today…

* * *“Get up, Valery. Get up!”

Mama was shaking me by the shoulder. I opened my eyes and squinted from the bright electric light… Had I overslept? No, day was just breaking.

Mama didn’t go to the kitchen to fix breakfast as usual but sat down on the edge of my bed. That was strange… She was pale, her hair disheveled. That was also strange. She usually did her hair after getting up, and then she woke us up. She propped her disheveled head on her hand, her elbow resting on her knee, and said quietly, “Grandpa died…”

Perhaps, in a child’s mind there isn’t, nor can there be, the feeling of the loss of a relative that adults experience. Nor is there the feeling of despair that something in your life is over for good and will never come back, an almost physical feeling of loss, of horror in the face of something that is beyond repair, in the face of nonexistence.

My feeling of loss was quite different.

Grandpa Hanan was gone. It meant that I would never hear the joke with which he always greeted Emma and me, “Your mama is ai.” And he liked to say it even after we grew older. I wouldn’t see the way he stuck his hand under his skull cap to scratch his head. And suddenly, I visualized that, and many other scenes, as if on a screen.

“Get dressed, quickly,” Mama’s voice was now heard from the kitchen. I hadn’t noticed that she was no longer sitting next to me. “Get dressed, wash yourself. We’re going to Tashkent.”

Grandpa had died today. It meant that his body had to be committed to earth today. That was the Jewish custom, and those customs were observed very strictly by our branch of Jewry in these parts.

Our whole family, the four of us, set out on our journey.

Our bus station had just received new Icarus buses made in Europe, which were big and comfortable. Those Icarus buses seemed to us a miracle of technology and embodiment of beauty compared to the old, run-down, domestically made buses, which resembled slow crawling beetles, which were stuffy, crowded and shaky. The Icarus buses ran smoothly and fast.

This time, it seemed to me that our bus was going terribly slow. The forty-five-minute ride from Chirchik to Tashkent seemed to last hours. Even the trees along the road, which usually flashed by quickly outside the windows, slowed their run.

At last we were there. We walked across Old Town along the familiar Sabir Rahimov Street. In the schoolyard on our right there were many children, a long recess must have begun. The laughter and squealing were so loud that they rang in my ears. Girls were skipping rope near the metal fence. They were carefree, unlike us, as they skipped and counted, “Bir, ikke, uch…” Girls, with sun-burnt faces, wearing skull caps, their myriad thin black braids bouncing down their shoulders and backs… This was an ethnic school. Classes there were taught in Uzbek. And I remembered that Mama had also attended an Uzbek school. She had worn a skull cap and made many braids. Her father was still young: Grandpa Hanan…

“Ester!” a familiar voice called to Mama. A car that was going in our direction put on its brakes near the sidewalk, and Uncle Avner, Mama’s brother, looked out of the window. “Ester, we are taking Papa to Samarkand. Will you go with us?” “Already?” Mama whispered, gave her travel bag to Father and ran to the car.

* * *It was quiet in Grandma Abigai’s yard, even though there were many people. Grandma, wearing a black dress and a headscarf, got up from a low stool when she saw us. She hugged my father, gave Emma and me a pat on the head and asked quietly, “And where’s Ester?… I see… She’s gone with him… Yes, he’s gone, he’s no longer with us…” Grandma nodded her head and looked at us, as if answering our question, “Where’s Grandpa?”

Grandma Abigai’s eyes were red, her eyelids swollen. I thought that perhaps there were no more tears left in her eyes. But Grandma sat down on the stool again and began to cry, burying her face in a handkerchief and slapping her knee lightly. Her three daughters, Marusya, Rosa and Rena sat next to her. The collars of their dresses were slightly torn as a sign of grief. That was an old custom.

Emma and I made ourselves comfortable on one of the long benches near the gate. Our cousins, Robert and Boris, were already there. Boris was my age. He was Uncle Avner’s son, a serious boy who was praised in the family. He had been studying violin for several years.

As I sat down, I looked around. There was an old bed across from us at the door to the house. It was covered with a dark cherry-colored, patterned carpet, attached to the wall and hanging down onto the bed, on top of the korpocha, a padded mattress. Grandpa liked that carpet very much, and now his photograph was attached to it.

The old bed was Emma’s and my favorite place in the yard. We particularly liked to jump on it. Its metal net was just as good as a trampoline; it bent under our weight, then sprang back again. We would jump up and down, up and down, squealing with delight. The bed would answer us in its squeaky voice, kir-rr-kirrrk. It seemed to enjoy stretching its old bones.

Grandpa used to come out of the house at the height of our merriment, holding a bowl of fragrant tea. We would stop jumping. “Ah, you pranksters,” Grandpa would say and sit down on the bed. Flushed with excitement, we clung to Grandpa and stroked his short beard. Grandpa’s face, always somewhat pensive and tired, softened, became smoother and younger when he smiled. Then he would begin our game, which was always the same.

“Your mama is ai!” Grandpa repeated, pinching us lightly on our necks, bellies, chests. He did it tenderly, without hurting us, but we were very ticklish. We squealed and wriggled but didn’t try to break away. On the contrary, we hugged him even tighter.

It seemed to me that Grandpa loved us, but not the way Grandparents usually love. He enjoyed our company as an equal, and whenever we were together, he turned into a child.

There were our two warm bodies next to his, big, worn out, tired… Was it possible that it didn’t just give him joy? Perhaps, it gave him strength.

As he played with us, Grandpa would often begin to cough. His cough was hoarse; it lasted a long time. He bent almost to the ground, trying to clear his throat, but he didn’t always manage to do so. If he did, it didn’t help for long. Hugging him tightly, I felt, almost always, a wheezing and bubbling in his chest.

* * *…I continued looking at the old bed, on which other people were now sitting. Neither Grandpa nor I were there. Never again would he sit next to us there. It was his portrait on the carpet instead of him, as if replacing him on that sad day when we were seeing him off. I wanted to look at his portrait, but it was also scary.

Meanwhile, the remembrance ritual continued the way such rituals were done in every Jewish family. They were not much different on the surface from Asian rituals. Lamentations, sniffling, sad exclamations were heard now and then.

“Why have you abandoned us?” the hunched over old woman exclaimed melodiously. She looked up and rocked, lifting her hands to the sky. She was Buryo, Grandma Abigai’s sister, who had arrived from Samarkand to take part in the ritual, not only because custom required it. Buryo really loved and respected Grandpa, who had helped her and her family generously many times.

Several other women joined in Buryo’s lamentations, including my aunts.

“Father, Father, you’ve abandoned us orphans! Why?” That’s how they lamented, rocking backward and forward, raising their hands to the sky, patting their knees and stomping their feet slightly.

When I was a child, I, naturally, didn’t know much about funeral rituals. It was later that I, unfortunately, became acquainted with them. On that day, we children just watched everything that was going on with curiosity, no more than that. I, for one, mourned Grandpa very much, but I would never have agreed to shout about it in front of everybody, and not a single child would have. Perhaps, tolerance for many customs and understanding the need for them comes with age.

When I saw how sad Grandma’s eyes were when she looked at the old tree in the middle of the yard, my heart tightened. That tree had stopped blossoming and dried up not so long ago. It had grown on the spot laid with light bricks, and it had become almost as light. Slightly bent, with outstretched boughs, it made me think of a figure frozen in the middle of a rapid-flowing stream in a desperate effort to keep its balance. Grandma had been upset when the tree dried up, and she often repeated, “It’s a bad omen.” But her eyes were drawn to the tree now and then. Maybe she remembered about the bad premonition, or maybe she was thinking about her resemblance to the lonely, dried-out tree trunk.