Полная версия

Полная версияEverything Begins In Childhood

“I’m sorry for Uncas,” Vitya Smirnov sighed. “Go, children of the Lenape. Manitto’s wrath has not been exhausted…” I said slowly and sadly. Quite recently, urged by Vitya, I had read “The Last of the Mohicans,” and now we talked about the book, played its heroes, and discussed everything depicted in it, often with indignation because many things didn’t sit well with us.

No real historical events were important for us, especially in faraway America, not the war between the English and the French nor relations between the palefaces and the redskins.

What was important to us was the fight between good and evil. We felt that good had to triumph, by all means. It had to. But why did Fort William Henry fall in battle? Why did the Hurons slaughter the defenseless women, who had left the fort, in front of everyone?

We didn’t forgive the author either for “unnecessary” battles or pointless sacrifices, especially the death of our favorite hero, Bounding Elk, or the beautiful Cora, Colonel Munro’s daughter. They perished, but despicable, treacherous, cruel Magua destroyed everybody and survived almost through the last pages of the book. Why did James Fenimore Cooper permit such misfortunes? No, the book should have ended a different way. We blamed Cooper for everything as we encountered the cruelties of history for the first time. We didn’t yet know much about history, or life in general.

Before breaking up, we agreed to a forthcoming battle against the Iroquois – when, how and what we needed to prepare. It would be a glorious battle! There were many battles in “The Last of the Mohicans.” We chose one at a time. Of course, we had to simplify everything, to modify, omit some details of the plot, and even do without some of the characters. There was nothing we could do about that.

We dedicated the time before a battle to preparing our arms. Each of us had his own arsenal. In the past, we had been pilots, members of tank crews or artillerymen, and all our arms looked accordingly. Now, we had to change them. After all, we were Indians.

When Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn were preparing Jim’s escape, romantic Tom demanded that everything be done as in his favorite book about the escape of a prisoner. They even had to dig the tunnel under the wall with a knife instead of a shovel. As the more practical Huck had foreseen, nothing came of it.

Like Huck, we weren’t so literal. We understood that we couldn’t even dream of “real” Indian weapons. We had to adapt whatever we had on hand, slingshots, for example. Before, we had made a cannon with pebbles for cannonballs. Now, we decided it would be a tomahawk. We wouldn’t use pebbles any longer, one might knock an eye out with them. We would use a bent piece of wire, which we called a “dowel.” It was safe and could sting badly – “ouch, ouch, ouch.” We could also use our rifles. We called them zhevelushniks. The base was a piece of wood to which a metal tube was attached. A pointed window latch with a piece of thick rubber was attached to it and fastened to a rifle butt. If we put the cartridge from a starter’s pistol, zhevelo, into a tube and pulled that powerful trigger, it would produce a marvelous din.

Zhevelushniks had served as submachineguns and other modern arms. Now, they became long-barreled flint rifles. The metal tubes we used in class to shoot chewed-up blotting paper or paraffin could be used for that purpose. There were also bows, and those were almost like real Indians’ weapons.

So, a battle lay ahead.

The hated Hurons, also known as the Iroquois, had abducted Alice and Cora, the daughters of the English Colonel Munro, the commander of Fort William Henry. That heinous abduction was committed under the leadership of Magua, Sly Fox. We all hated him bitterly. It was he who would kill Uncas.

It was no easy task to find a boy who would agree to portray him in a battle, but we found one.

Zhenya Zhiltsov agreed to do it. We considered his deed very magnanimous, though we suspected that Zhenya simply wanted to be a leader.

Zhenya and his four friends, the group of Iroquois, armed to the teeth, were making their way through the forest and would run into our courageous group, the Mohicans and Hawkeye, our pale-skinned friend.

A whole series of battles, chases and sieges would begin at that moment. That was how it began in the book. Could we possibly depict all that?

We would have only one battle. Where could we possibly get the captives, Alice and Cora, over whom the whole thing had started? Could we allow girls to join our game? Absolutely not!

So, we decided that the captives would be only “as if.”

We, the Mohicans, were supposed to win, according to the book. But who knew how the battle would turn out, our battle today?

* * *After stealing secretively, one by one, into the vegetable gardens, our detachment arranged an ambush among the dense undergrowth of the hedge.

Our vegetable gardens, even though we called them so, were also fruit orchards. Bounded on one side by the wall of the building and on the other side by the fence of the kindergarten at a distance of about twenty meters, they were perfect for playing without being disturbed. We could sneak in there and set up ambushes.

To our delight, some tenants had long given up on vegetable and fruit cultivation, so their patches were overgrown with weeds and shrubs.

But we also appreciated the hard-working gardeners. It was great to hide among the tall grape vines on the Ogapians’ patch or in their neighbors’ orchard among the apple and cherry trees. They were excellent. These various gardens effectively reproduced the impassable woods on the banks of the great Hudson.

We ensconced ourselves in the shrubs. The sun warmed the backs of our heads with rather great intensity. That was good because the sun would dazzle our enemies if they, as we assumed, were to appear from the left corner of the building.

From behind me, I heard the frightened chirp of a sparrow, sounding as if it were in the middle of a fight… That was Chingachgook-Rustem Angherov signaling from the tree near the transformer booth. Rustem could imitate birds so well it was impossible to tell the difference. “They’re approaching,” Vitya, who lay low nearby, whispered. “That was the signal.”

As we had agreed, I signaled with a hand mirror. It caught a sun ray and sent it back. The shrub behind the hedge moved slightly – Uncas-Savchuk had seen my signal.

And almost immediately, a flock of pigeons, their wings rustling, flew up from the pigeon house perched on the tall pole above the Oparin’s vegetable beds. Certainly, something had frightened them, just as the rustling of leaves or cracking of a branch would frighten off a deer in the woods. The Iroquois were not cautious, not cautious at all. And here they were…

Bending low, they slowly made their way along the wall of the building. A fringed brown corduroy sleeve flashed by; that was Magua-Zhenya. Feathers swayed above the shrub… They were near. We could hear the rustling of their sandals and their irregular breathing… But we were waiting for a signal, a command.

“Ouch!” one of the Iroquois shouted and dropped his bow. Well done, Chingachgook! Well done, Rustem! He had hit the enemy in the arm with his slingshot, which meant, of course, that he had thrown his tomahawk with precision… And then, we shot out of our hiding places, and the battle got rolling.

I took the metal pipe out of my pocket, my flint rifle, which inspired horror in the enemy, and looked around calmly.

I wasn’t just anyone, I was Hawkeye, and I had to behave with dignity. Aha, that’s Magua! I shot, and a blob of paraffin hit him on the forehead, which meant that I hadn’t disgraced the famous name of my hero.

According to the rules, Magua had to leave the battlefield after being killed, but who remembered rules in the heat of the battle. If we followed the book, I wasn’t supposed to kill Magua. We all got excited, and Zhenya was furious. He raised his ancient flint rifle, that very zhevelushnik, aimed it at me and was about to pull the trigger… At that moment, a thick spurt of water hit Zhenya in the face. That was Uncas-Savchuk, who had arrived in time to help me with his plastic water sprinkler; in other words, he had thrown his hunting knife accurately at Magua. Magua, doused with water, lunged, and the rifle went off in his hands making a deafening sound, but he missed. Yes, he missed!

Our enemies were definitely weaker than we. We, not without argument, took them out of action, one after another. Victory seemed very near. All we had to do was set the captives free and scalp the dead. But suddenly…

“Get out of here, you hooligans! What the devil has brought you here?” a disgusted woman yelled through a fourth-floor window. “Just you try to shoot again! Get out of here! I’m going to get Nikitich!”

We didn’t want to get mixed up with her husband Nikitich, who was always drunk. What kind of game could it be if someone yelled at you through the window? Anyone was welcome to yell at us when we were kicking a ball; it might even be more fun that way. But this game of Indians was not for the eyes of strangers. It wasn’t just a game; it was more than that…

Some limping, others ouching, we trudged out of the vegetable gardens. As we walked, we continued to argue and swear, blaming each other for breaking the rules of battle, but even worse, for deviating from the plot of our favorite book.

* * *I was lucky to have friends who, like me, were bibliophiles. Perhaps that very passion strengthened our friendship most of all. Vitya Smirnov had so many interesting books on his shelves. And Igor Savchuk was simply addicted to books. The moment we had free time from school, we rushed either to a bookstore or to the local library on Yubileynaya Street. My building was on Igor’s route, so we usually went there together.

“Igor, Valery, it’s so early, and you’re already here!” The librarian Anna Sergeyevna welcomed us with a surprised exclamation.

We actually showed up at the crack of dawn most of the time. Anna Sergeyevna must have become used to it. Her surprise was probably a pretense, to some extent. She was usually glad about our early arrival and our zeal for reading.

What urged us to go to the library early in the morning over the weekend? We feared that the book we had noticed on the shelf the last time might have been borrowed by someone else, that there were another Savchuk and Yuabov who had the same taste.

“Let me turn on the light and take off my coat,” Anna Sergeyevna continued, grumbling, still pretending to be annoyed. She was young, not tall, with short hair. Now, she looked like a roll because she was pregnant, and she felt a little self-conscious around boys. As she was taking off her coat, she thought up an urgent task for us, “There are shovels in the corner. Why don’t you clear off the snow at the entrance? Snow piled up during the night, and it will be a good exercise for you.”

As we were scattering the snow diligently, Igor muttered:

“It was there yesterday, on the upper shelf on the right.”

At last, by pulling strings, so to speak, we were in the desired room, like the most avid of readers. That was the reading room. It had the best books, but they could only be read there. We were no strangers here, and Anna Sergeyevna trusted us. We could go to the shelves and take whatever we wanted home.

“Here it is!” Igor said, taking “Quest for Fire” off the shelf.

Going to the library was not the only way to get interesting books. Another way was to include more boys in the exchange. Let’s say Igor took “The Mysterious Island” from someone, held it for a week and gave it to me to read. And I gave him someone else’s “The Diamond Thieves.” We did it casually because we had confidence in each other; we knew that the books wouldn’t get lost or damaged.

The members of our group had a special attitude toward books. We always made dust jackets out of paper and gave them “first aid,” if necessary. And we were always indignant when a book was returned tattered, with a detached spine, turned up pages, or some ridiculous inscription, such as, “To my Little Sweetheart from the Little Tom Cat. Send me a note. I’m waiting impatiently.”

“Who is this Little Tom Cat? I’ll tear his head off,” the always neat Igor grumbled.

In a word, in order to read books, we needed to obtain them. Buying books and putting together a decent home library was an almost unattainable dream.

To buy didn’t mean to go to a bookstore, pay for books and… no, there were rarely any books on bookstore shelves that children and teenagers liked. Very few were published, and they were distributed in a very crafty way. First, one needed to recycle paper and rags for a long time. It took a long time because recycled stuff would be exchanged for books by weight. If not enough stuff was recycled, books weren’t made available. Besides, you didn’t get what you wanted but what was in stock at the time. You had no choices.

* * *In the evening, after it had grown dark, we gathered around the fire again. We talked about the battle, argued, then calmed down.

Plexiglass was certainly not an oak log, but its flame was as beautiful as any flame. We sat without talking, bent over the fire, our heads almost touching. Tongues of flame intertwined intricately. They swayed, their form changed, now they bent down to the earth, now shot up toward the sky. And we stared at them, unable to tear our eyes away.

“You know what?” Vitya Smirnov suddenly said. “Let’s get together here after we graduate from college. How about it, guys?”

“In ten years…” Igor Savchuk shook his head in doubt. “But what if we have all gone in different directions by that time?”

“Ah, you, Uncas,” Vitya chuckled resentfully. “Go off in different directions, get married.”

“Stop, stop!” Rustem stood up and waved his hand imperiously. “Stop, gentlemen! Mr. Smith, Mr. Pencroff… Gentlemen, do you remember the bottle?”

“A note!” I jumped up. “We’ll put a note in it.”

“And we’ll throw it in the canal,” Zhenya Andreyev said sarcastically. “And it will float down the Chirchik River to the sea.”

“We’ll bury it here,” I said slowly. “And in exactly ten years…”

Within a few minutes a bottle and some paper were brought. We had already found an old shovel and began writing a message to ourselves.

“We pals from the neighboring buildings,” Rustem was writing precisely on a sheet of paper as he listed our names, “decided to put this note in a bottle and bury it, and we promise that in exactly ten years…”

The lemonade bottle with our note in it was closed tightly, neatly wrapped in rags and placed in a plastic bag. Our bottle lay in a deep hole dug in a safe place, well covered with soil, stomped with our feet, leaves piled on top of it.

We stood under the clear sky, studded with stars, and felt amazingly good because we had realized the utter importance of our friendship, and we didn’t want to lose it.

Chapter 42. The Order

Of all the jewelry Mama had, I somehow remember her earrings, the ones Grandma Abigai had given her. They were very beautiful antique earrings. Grandma used to wear them and then gave them to her daughter: three big pearls, each the size of a pea, with a little gold pin stuck through each of them, forming a triangle. It was surrounded by a setting of dull gold. “Old gold,” as it was called, had the subdued luster of precious metal. When Mama put the earrings on, she became even more beautiful. She had a proud bearing, a hairstyle with a big bun on the back of her head, thick Eastern eyebrows that looked like two crescents, and a beautiful curve to her tender lips. It seemed that the earrings swinging in Mama’s ears illuminated her face with a mysterious light that emphasized her beauty. But our life took such a turn that before we emigrated the earrings had to be sold, for we needed money. Now, I have neither Mama nor her earrings in my life, but I can still visualize her the way she looked in those distant years. I remember how the earrings shone swaying from her ears, particularly on that unusual day…

* * *“Valery, get up! Valery!”

I opened my eyes.

What a miracle that was! It was my father waking me up instead of Mama. Besides, the broad smile on his face was also a rare thing. And he was shaking something that looked like a medal in front of my face.

“Do you see this? Mama’s been awarded an order!”

“Wow!” I stretched out my hand. “Show it to me.”

“Later, later. Get up quickly. Let’s go buy flowers while she’s asleep. Dress quickly.”

And Father ran out of the room.

I dressed immediately. Of course, I did – Mama had been awarded an order… Father’s happy face emphasized the extraordinary nature of what had happened. He wasn’t happy often, and I had never seen him rejoice on Mama’s account.

It was six in the morning. Mama was fast asleep. She allowed herself an extra hour of sleep after the night shift only on Sundays. Papa closed the door behind us quietly, trying not to make noise.

Chirchik seemed deserted that early autumn Sunday morning. The cool air was fresh and didn’t smell of gas fumes. The sun’s rays already shone slightly on the treetops.

But as soon as we entered the bus, the feeling of morning stillness and absence of people evaporated. There were no people on the streets because they were all riding buses, and the majority of them were on their way to where we were heading – the bazaar. They almost all had some kind of bag in their hands; some even had pails. Their faces wore concentrated expressions as if they were pondering the quantities of merchandise they planned to buy at the bazaar.

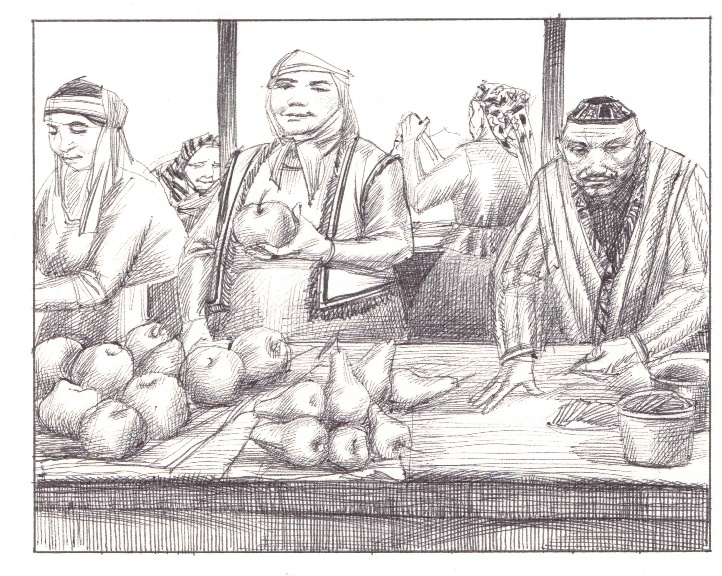

Ah, those Eastern bazaars! A sight that presents Asia in miniature with all its most typical features, customs, ways of life – in a word, all its flavors. Eastern bazaars have succumbed to the impact of time much less that all the other forms and signs of city life. The goods they sell have remained the same for centuries. Interactions between buyers and sellers, their jokes, gestures, traditional exchange of remarks – all that has to be seen and heard.

I have already written about the Tashkent bazaar. The Chirchik bazaar was smaller but, perhaps, because I was older, I have more impressions of it, more fuel for my imagination.

Surrounded by a high wall with a big gate made of metal rods forming a beautiful pattern, it looks like a medieval fortress. There are always crowds at the gate and the walls. Who are they? A caravan has just arrived. It has traveled across the desert for a long time. Tired travelers unload their bundles and sacks from camels – I prefer not to notice that some of the goods are piled up in parked vans. Now, after fortifying themselves with food and taking a rest in the shade of the city walls, the caravan travelers go through their goods, talk to the locals, discuss prices… And a city guard wearing an armband and holding a batch of tickets in his hands charges payment for entering the town with goods, to be precise, for the right to sell at the bazaar.

When you walk through the gate, you step from a relatively calm and leisurely environment into an environment that brings to mind a cauldron of boiling soup.

People scurry and swarm, forming crowds. The rumble of many voices hangs in the air above the crowd. It’s a huge choir with many participants – some of them stand behind cement counters urging buyers to look at their goods and praising them in ringing melodious voices. Others crowd around the counters and bargain, straining their vocal cords.

Now, in the fall, the counters are piled with the riches of everything that grew in the local fertile soil during Asian summer. Apples sparkled and shone as if they were still lit by the sun. Juice almost burst from pears. Transparent bunches of grapes were either dark, fragrant with a thin whitish coating or sparkling like gems… Scarlet cherries, bluish plums… and peaches! And mountains of watermelons! And oblong melons enveloped in a cloud of delicate aroma! Vegetables were just as picturesque.

“Sweet carrots! Djuda shirin!” sang an old man with a beard and an orange skull cap on his head that looked as if it had been made from his carrots. He looked like my Grandpa Yoskhaim very much. Just like other sellers, this old Uzbek praised his goods in Russian since almost everyone spoke Russian in Chirchik. This Russian was sometimes distorted, and it was always distorted by sellers at the bazaar – the endings of words were changed, genders and cases confused. It had become a sort of a pidgin.

We stopped. “Here it is, try it, my dear,” the old man extended a peeled carrot to Father. “It’s like sugar. You can find it only in my garden.” Such a treat didn’t create any obligation. On the contrary, a buyer was expected to honor a seller by performing this ritual before opening his wallet.

Father took a bite of the carrot with the air of an experienced taster, nodding his head. “Yahshi?” the old man asked. A seller who shared a counter with him was already offering Father one of his carrots, “Try my carrot. My soil is better.” “Hey, amak! Let him finish chewing!” the old man who looked like Grandpa Yoskhaim waved his hands.

Please, don’t think that it was the beginning of a squabble that could end up as a quarrel. No, such haggling over buyers was an old and generally accepted tradition.

Father paid no heed to the competitor’s call, and he bought some carrots from the old man. Naturally, he bargained a bit; otherwise it wouldn’t have been a proper purchase.

Almost all the sellers were Uzbek kolkhoz (collective farm) members. What they sold had been grown with their own hands in their private gardens. And what did they grow on the kolkhoz’s fields? What did kolkhozes sell at the bazaar?

There was a kolkhoz booth not far from the entrance. The stench of rotten potatoes coming from the booth was so strong that no one wanted to enter it. The shelves in the booth were always half-empty. “That’s how the government takes care of the people,” folks would say, for they had forgotten that kolkhozes were not government enterprises, but collective farms, in other words, the collective property of the people. However, it was easy to forget that…

The meat counters came next. Piles of meat lay on the counters and hung on hooks. Nobody paid attention to the swarms of flies. They flew away every time a butcher picked up another piece of meat.

At last we passed the grocery counters and approached the flowers. That was a special corner of the bazaar. There was neither a crush of people nor noise nor sellers haranguing buyers there. Obviously, the owners of these goods had a different attitude about their trade and a different feeling of self-respect. We walked among gladioli, lilies, daisies and roses for a long time before Father stopped in front of one of the sellers. A nice-looking Russian girl who spoke clearly and melodiously, to whom I listened with pleasure after the bazaar’s garish vernacular, helped Father pick out roses. “She’s received an order? How nice,” she said going through the long stems with their tight buds. “This one is very nice… and this one too…”

* * *As we were leaving the bazaar, we walked along the outer rows, which weren’t crowded. A group of babais – that was how we jokingly called elderly Uzbeks and Kazakhs – had made themselves comfortable in the shade of an apple tree near the fence. They sat cross-legged on a mat and talked unhurriedly and calmly as if there had not been a noisy city bazaar around them but rather meadows surrounded by mountains. Yes, they were shepherds, which was clear from their appearance – they all had moustaches and beards, with shaggy hats on their heads, dressed in long chapans, which covered their boots. There was a teapot on the mat in front of them, and each of them held in his hands a bowl with steam rising from it. Some of them sipped tea, other enjoyed nasvayem, chewing tobacco that one placed under the tongue. And, of course, there were horse-hide containers nearby filled with kumis.

“Oh, it’s kumis… Let’s have some,” Father suggested.

I kept quiet. Kumis was sour mare’s milk. What’s good about it? But Father had already asked the sellers: