Полная версия

Полная версияEverything Begins In Childhood

I sighed and asked, “May I go to the movies?”

Mama nodded.

“Go. Here’s the money… Listen,” she suddenly asked. “Will you take Emma with you? Just hold her hand. Just be sure to hold her hand the whole time.”

* * *The October Movie Theater was a three-minute walk from our place. The three-story brick building was located on a hill and, for that reason, reminded me of a fortress. The movie theater’s back wall faced our building. That was where the exit for spectators and the basement to which a short staircase led were located. The basement attracted us boys, no less than the auditorium with its movies.

It was a workshop, or an atelier, as its master, Uncle Petya, preferred to call it. In our opinion, Uncle Petya was the best artist in the world. He painted posters to advertise upcoming movies. We considered those posters wonderful works of art. However, it seems to me, even now, that they were expressive, colorful and detailed.

Uncle Petya was a kind, sincere person. We once stopped by his atelier by accident, and soon became habitués. As soon as we showed up, a welcoming exclamation would be heard, “Ah, guys, it’s you! Come in, come on in!” And we didn’t make him beg us. We spent long hours in Uncle Petya’s atelier, especially when it was raining. There, in the basement, days never seemed rainy and drab. It was always light and festive in that small room crammed with posters, canvases on frames and cans of paint. Our favorite characters looked down at us from the posters. Uncle Petya, brushes in his hands, worked wonders on the canvases, and another adventurer, noble knight or warrior would appear on them. We met Captain Nemo, Robinson Crusoe, a kind policeman in evil and merciless New York City, and a great number of other characters before the movies were released.

Sometimes, we became Uncle Petya’s collaborators, well, perhaps not collaborators but consultants. For instance, let’s say he was painting a poster for the movie “The Last of the Mohicans.” We stretched our necks the better to see the sunburnt figures of the Indians that appeared on the canvas. They were Chingachgook and his son Uncas.

Suddenly, someone’s voice broke the silence. “You have it wrong, Uncle Petya. They paint their faces dark red before a battle. You have them pale.” Or “Un-n-cle Petya! What about the tomahawk? There should be leather strips on the handle. Don’t you remember?”

Uncle Petya, puffing his pipe, would nod with a serious air and repeat, “That’s my boy, that’s my boy. Thank you.” And he made the necessary corrections. Perhaps it wasn’t that important, but we were very proud of our contribution to his art.

A line would appear at the box office, sometimes a very long one, as soon as a new poster went up at the main entrance. We were absolutely sure that it was Uncle Petya’s skill that brought people to the movie theater. After making ourselves comfortable on a bench in the little park in front of the movie theater, we would watch people examine a poster closely, trying to guess what impression it made on them and arguing about it. We enjoyed our superiority over other people. Just imagine, we already knew what the next poster would be! We knew, and these people didn’t.

* * *It was almost dinner time as we returned from the movie theater, very satisfied with yet another “Fantomas.” Every episode of the series seemed wonderful. They shot, sank to the ocean depths and raced in balloons in those episodes.

As Emma and I were entering our building, Uncle Kolya, our neighbor, called to me. “Valery, listen…” he bent over the railing and spoke louder, “There was a lot of noise at your place… Your parents were quarreling again… I knocked on your door, but they didn’t let me in… If anything’s wrong, call me, or just run to our place right away. Got it?”

I nodded and, still holding Emma by the hand, entered the building. “They quarreled.” I knew perfectly well what that meant. Father gave Mama another beating. It was about ten steps from the entrance to our door, but it seemed to me that ages passed before I inserted the key into the keyhole. The key didn’t want to go in. On top of that, Emma was weighing my right hand down.

The clang of the lock and the clatter of the door seemed awfully loud in the quiet apartment. I looked around – where was Mama? But first I saw Father. He stood before the mirror in the bathroom, and it seemed to me that he was drying himself. I saw right away that the towel was covered with blood. And then, when he lowered his arm, I saw blood streaming from an open wound on his collarbone.

“What scum!” Father mumbled, pressing the towel to the wound.

“Mama!” Emma’s happy voice sounded in the kitchen. “Mama, we watched ‘Fantomas’!”

I rushed to the kitchen. Mama was sitting on a chair near the table, hugging Emma, who clung to her, with one hand, and the kafkir, the large flat spatula with another. A bright red spot had spread on it.

Mama’s face looked terrible. I didn’t want to look at it, but I couldn’t help it. Her left cheek was swollen, there was a dark crimson spot around her swollen eye, dried out blood on her lips, her hair disheveled. I rushed to her and hugged her, burying my face in her shoulder. She was mumbling, “It’s all right, son, it’s all right… Now he knows that I can do it too… Just let him try again… It’s all right, son. We’ll go visit Grandpa tomorrow.”

Chapter 37. Little Musicians and GooPoo

It may sound strange, but, when I was a child, I perceived the school as a living creature. I mean the school building itself. For example, I imagined very clearly what happened to it on the first day of the school year. I imagined that the school was at last awakened, like Sleeping Beauty, by hundreds of princes and princesses with ringing voices, after a very long hibernation, after many months of sullen, sultry, dusty stillness.

That stillness was broken suddenly. The bell was the first to end it. It continued ringing as the long corridors filled with the clomping of feet, as the thin walls began to shake with laughter and shouting, as the staircases hummed like a prairie under the hooves of bison running to a watering hole. It seemed that the glass in the windows glistening in the sunlight couldn’t wait to be shattered by a ball so that its tinkling would join in the general merriment.

That was inside the school building. And what about the outside? No, it wasn’t accidental, it certainly wasn’t, that the height of autumn coincided with the end of summer vacation. Autumn itself congratulated us on the first day of school, spreading its multi-colored carpet in front of the school building and turning the leaves fiery, clearly reminding us of the many pleasures awaiting us outside the school.

And we never forgot about them. No matter how the school enjoyed our lively return, no matter how eager our teachers were to stuff our heads with the subtleties of knowledge, the school yard was much more attractive.

Vzh-zh-zh! Vzh-zh-zh! Vzh-zh-zh was heard above the school’s round flowerbed.

A long recess. There were dozens of children around the flowerbed in the schoolyard. It was as quiet there as in a classroom in which the strictest teacher made sure no one talked. In fact, there was a kind of hunt underway near the flowerbed, and it required complete quiet.

“Little musicians” were being hunted. That’s what we called the small bumblebees. They were the same size as wasps, but hairy, and “dressed” in smart vests. There were very many of them. They circled above the yellow honeysuckle flowers, unhurriedly choosing a landing place to settle down on a pistil and get to the business of collecting nectar. There were many other insects, including big heavy bumblebees and wasps, feasting on the flowerbed. But we hunted only the little musicians. They were merry, energetic, swift and noisy. It honestly seemed to me that we and they were close relatives. It was sufficient to listen to their ringing buzz to feel that kinship. The little musicians’ melody was as clear and piercing as a child’s voice. They changed frequencies effortlessly, and that created the variety of sounds. In a word, the little musicians were our favorites. And we, naturally, had no doubt that they flew to the schoolyard especially for our pleasure.

“It’s about to alight,” I whispered.

I held a paper trap in my hands. It was a sheet of notebook paper cleverly folded to mimic the wide-open beak of a hungry baby bird that would shut tight the second its mother put a beetle in it.

Making and scrutinizing this paper trap was just one of the many technical innovations with which we boys began each school year. Practically all of us could share a story about something new we had learned over the summer when we returned to school from vacation. This new knowledge included new types of paper airplanes, boomerangs, crackers, soldiers’ caps and those very traps, one of which I was holding in my hands now. We improved some things and developed others. Parents could only throw up their hands – how could it be that a thick composition notebook recently bought was used up? They calmed down after hearing that many drafts had to be written and many clean copies made. They calmed down and were even satisfied with their sons’ diligence.

Their sons were quite diligent but in a different field of endeavor, so to speak. But was that so bad?

“It’s about to alight,” I whispered, attempting to breathe quietly.

Zhenya Andreyev, a friend from my class, and I froze near the flowerbed. A little musician, the one closest to us, glided above a yellow flower, either scrutinizing it, simply enjoying flying, or fulfilling a special bumblebee ritual. Zhenya and I didn’t just watch it, we felt as if we were gliding along with the little musician. We didn’t see or hear anything but this small creature whose buzzing sounds were close to our ears, and whose wings flapped so fast that only dull blurry spots could be seen on the sides of its little yellow vest.

Vzh-zh-zh-z… The flower quivered slightly, then began to sway… It had landed. The little musician closed its wings, extended its tiny tongue and directed it to the spot where the tastiest, sweet nectar awaited it. I opened the trap, my shoulders tensed, my muscles… Bang! It was done. It was caught. Oh, what a happy moment that was!

Yes, that’s what we were about – the ardor of the hunt was so exhilarating that every catch seemed like the first one, every bit of good luck called forth exultation.

The white “walls” of the trap vibrated in my hands. The little musician now beat against them, now buzzed. It buzzed excitedly, very loudly and clearly.

“Wow! Listen to it!” Zhenya laughed.

We brought our ears close to the trap to enjoy the concert. Now, we could brag about our luck and let other boys listen to how our little musician was singing and listen to the way their captives were doing it.

Some hunters, those who were more adroit, managed to catch two, even three bumblebees in one trap. They had a whole orchestra playing inside it. Everybody came running to listen to such a concert.

“Spit on your hand and rub it. You could also put plantain on it,” we advised Vitya Shalgin.

In the heat of the hunt, he hadn’t noticed that a little musician had stung him. Now, he had a red blister on his neck. It hurt a lot and it itched terribly. Everyone in class would watch the hunter’s agony, and the teacher… We would be having history class, and our teacher…

The bell rang loudly. Was it time to go already? Recess had passed so fast. We set our prisoners free. The lively creatures immediately resumed their flight over the flowerbed as if nothing had happened and continued their occupation in a businesslike manner. They were luckier than we.

* * *There were thirty students in class 5B, seventeen girls and thirteen boys. We had nothing against this ratio for we had already begun to appreciate female company. And we considered our girls very likeable. Notes were exchanged, paper airplanes flew back and forth, not to mention exchanges of glances, giggling and other displays of attention in class. It happened in almost all classes except history.

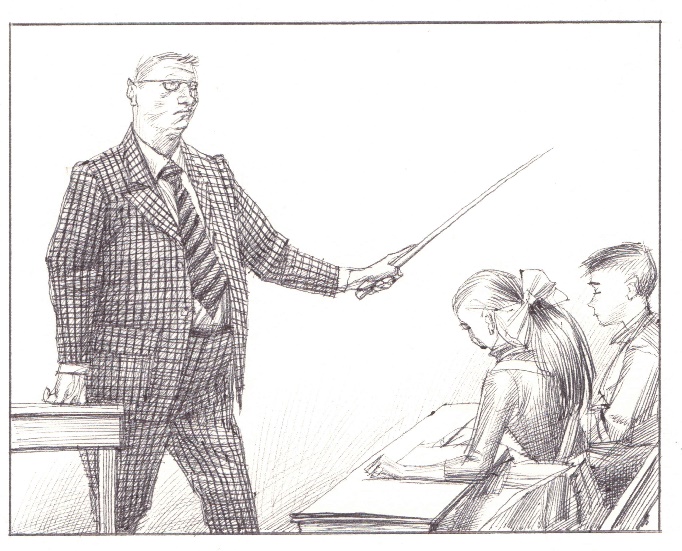

Deathly silence reigned in history class. All attention, everyone’s gaze was directed at the history teacher, and at him alone, in history class. If anyone tried to break the silence or became distracted, an F for behavior was inevitable. One could also be called to the blackboard, where something quite unpleasant could happen.

History was taught by Georgy Vasilyevich, but in our class, just as in every other class, he was called “GooPoo.” That was a very exact nickname because there was something slimy about him. Add another consonant, and it will be clear what we all meant. But even without the added consonant, the name was quite expressive.

We were not lucky with teachers. There were hardly any about whom we could say, “That’s quite a teacher!”

One of the exceptions was Yulia Pavlovna who taught geography. That pleasant, calm woman seemed not to make any special efforts to captivate us. She simply loved her ancient science and took pleasure in sharing with us what she knew. And one more thing – she treated children nicely. We who had just been fighting during recess didn’t notice how we turned into knights or crossed an ocean on merchant ships, prepared for a fight with pirates or floated in weightlessness in a spaceship in her class. Of course, we remembered all that, and when Yulia Pavlovna asked questions, all hands went up. From all directions one could hear, “May I answer?”

We all admitted that Yulia Pavlovna was quite a teacher. And such recognition is not something that came easily from kids. We scoffed at our teachers most of the time, seeking out their funny features and foibles. One of them would look at his shoes all the time, removing every speck of dust from them, while another delighted in picking her nose.

Georgy Vasilyevich surprised everybody. It wasn’t any single habit. His whole person was… In a word, his nickname GooPoo was not accidental.

In class, GooPoo behaved either like a tamer of beasts in the circus or a warden at a camp for juvenile delinquents. He walked up and down the aisles all the time. His pacing had certain rules, which he observed precisely. First, GooPoo would stop in the middle of a row, standing up straight, as if at attention. Then, after swallowing saliva, he would produce a very loud sound with his lips and tongue. Tsk-tsk was the approximate sound. Then he would take a few steps, beating his leg slightly with the pointer. That polished wooden pointer was always in his hand; he never parted with it. One got the feeling that GooPoo didn’t see children’s faces in front of him but rather a herd of wild horses. Phyut-phyut – his pointer, or rather whip, whistled softly from time to time, accompanying almost every word the teacher pronounced.

“I’m not” phyut - phyut “your Flura Merziyevna… or Izolda Zakharovna.” phyut - phyut “I won’t allow…” phyut - phyut “…nonsense in my class.”

For some reason, GooPoo thought that nonsense took place in the classes of our head teacher Flura, and physics teacher Izolda.

“I won’t allow it!” GooPoo repeated, lashing his leg once again with the pointer, going up on his toes, then down, and clicking his heels. That gymnastic exercise obviously raised our teacher above our class and other teachers. Perhaps, a rooster views himself as soaring above the whole world when he spreads his wings and stretches out his neck before crowing his cock-a-doodle-doo. After that, GooPoo would scan the class with his piercing eyes and proclaim, “There will be complete attention in my class!”

And then he would turn sharply and smartly, like a frontline officer, to his next victim standing at the blackboard. Zhenya Gaag was his victim today. Thin, pale, and light-haired, he shrunk so much under GooPoo’s gaze that it seemed he was trying to become invisible. The number of freckles on his face was increasing right before our very eyes… Zhenya had never demonstrated brilliance in class. It was hardly possible he would do so this time.

“Well, what can you tell us about the distinctive features of the primeval communal system? Summarize the material.”

It was that very system and its contribution to future social systems that GooPoo was teaching us, in his usual dry, boring manner, that day. The boredom could lull anyone to sleep. Since GooPoo would tsk-tsk, tap his leg lightly with the pointer and walk up and down the aisles while he delivered his lectures, it was impossible to doze. But it was also impossible to listen to attentively and remember it. Many boys in my class, including me, really liked history. When we did our homework, we read the textbook “The History of the Ancient World” willingly, and we didn’t find it boring. It was a good textbook, with many photographs and drawings, with interesting stories about expeditions and excavations, about the skeleton of a dinosaur found somewhere in the Sahara, about a cave, the abode of primeval people, discovered in the mountains of Europe. But there were no dinosaurs nor caves nor people wearing animal hides, no smell of smoke from a fire started with a wooden stick nor roaring of a mammoth whom hunters had driven into a deep hole in our history classes. There was no life in those classes.

Poor Zhenya! GooPoo continued swishing the pointer, repeating his command, “Summarize, summarize.” But Zhenya was shrinking even more and uttering incomprehensible sounds. He was like one of those primeval people about whom he was supposed to speak. However, such similarity could hardly be considered the teacher’s accomplishment.

“Congratulations on your D grade. Take your seat.”

After finishing off his victim, GooPoo turned to the class with yet another round of exercises. His pointer whistled as it hit his leg, then was raised, the point forward as if it were ready to fly off and pierce another martyr. The class sat motionless. Who would be next?

Dr-r-r-r! the bell rang out.

Hurray! What great luck!

Chapter 38. The Cold Morning

“Now tell me, Uncle, how’d it chance that

Our Moscow could be burnt to ashes…”

* * *It was quiet in the house. Everyone was still asleep. Grandpa Hanan fell fast asleep peacefully by morning. I had heard his hacking, seething cough throughout the night while I was half asleep. Now, repeating the lines of Lermontov’s poem, I listened to it unwittingly. The last time I was here, Grandpa hadn’t coughed so hard or so much.

“…Our Moscow could be burnt to ashes

And captured by the French?…”

I had come to visit my grandparents for the short winter vacation because Grandpa wanted to see me very much.

The famous poem “Borodino,” in the lines of which the raging battle resounded, was not difficult to memorize.

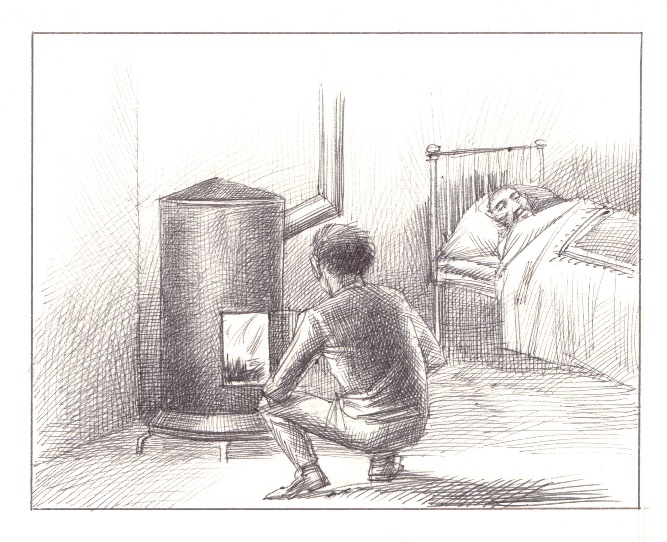

It was about eight in the morning. The bright crescent moon was high in the pre-dawn blueish sky above the yard seen through the window. The intense blue color grew paler and paler and the silhouettes of the houses in the yard grew clearer. I could see all that because I sat with my book at the window, framed by a thin lace-like design of hoarfrost. The window was cleared of ice in the evening, and the frost didn’t have enough time to spin a web of hoarfrost over it again. Other windows were fully covered by it. They froze because it was cold in the house in the winter, sometimes very cold. I woke up this morning because I was very cold, even though I slept under a padded blanket. I shivered as I got dressed and was chilled to the bone even after I dressed. The stove had to be lit right away.

When I visited Grandma Abigai and Grandpa Hanan in the winter, I was the one responsible for that. It had happened all by itself. Since I was a kid, I had hung around Grandma or my aunts when they lit the stove, pestering them with my nagging, “May I do it?” until they finally got so tired of me that once I heard, “Well, give it a try.” I was proud and happy. Fiddling with fire was my favorite thing. Since that time, I ardently made sure that no one violated my right while I was visiting. In the morning, I was the first to jump out of bed, shaking from the cold.

That stove… every time I looked at it, I would remember the big, floor-to-ceiling stove at Grandpa Yoskhaim’s house, which was hot day and night in winter, and it was always warm in the rooms. The stove here was tiny, like a chubby child, even though it was called a “bourgeois.” Probably, to those who named it that during the civil war, even such a small stove seemed a luxury. It was made of metal, round and just a meter high. It rested on short legs. There was a small bulging door on one of its sides, and a long flue – on the other, its lower part was parallel to the floor, and then it shot up at a right angle and went outside through the fortochka (a small window cut into the upper part of the larger window). There was a removable cover on top of the stove. It was very convenient to put fuel into the stove through it and then replace the cover. A kettle could be set onto it to boil water for tea, and then one could just watch through the little door to see how it was doing and add small pieces of firewood. Grandma sometimes even cooked on the stove, but usually it was heated with coal.

That morning, a pail of coal brought from the storage room the evening before had been placed near the stove. Wooden chips and old newspapers were also there. I put newspapers and chips into the stove, with coal on top of them.

Shaking from cold – faster, faster! – I struck a match. The bright flame blazed up. It attacked the newspaper and began to gobble it up, then switched to the chips. Hold on, flame, we need time for the coal to become red-hot! But the coal was not in a hurry. Fiery flames enveloped it from all sides; they hugged and licked it, but the black pieces of coal looked cold.

At last, white or slightly blue-gray dots began to appear on its surface. They spread and widened, becoming shimmering spots. The flame around them grew smaller; it was dying down, but the coal wasn’t blazing with heat. I felt it getting warmer and warmer; the “bourgeois” emitted a steady heat.

That little stove had its merits, its thin metal walls got hot very quickly. They also got cold quickly, as soon as the coals burned down completely. But now, I was taking pleasure in it. First, my palms, held above the stove, warmed up. Then waves of hot air began to envelop me, getting under my clothes. My elbows, shoulders, knees and the sensitive spot on my back between my shoulder blades were the first to feel it.

What a delight it was!

When I grew too hot near the stove, I put a kettle of water on it – Grandma prepared it in the evening – and made myself comfortable at the window with Lermontov’s poem in my hands.

“…The Frenchmen learned a fair amount that

They didn’t know of Russian combat,

For we fought tooth and nail!

The earth, just like our chests, was quaking;

The horses howled, their manes were shaking;

A thousand shouts and shots were making

One never ending wail …”

At that moment, banging was heard behind my back, as if continuing the scene of the battle. It was not as loud, of course, but I started. That sound came from dishes in the kitchen. I had been so busy with the stove and Lermontov that I hadn’t noticed when Grandma came out of the bedroom.

The kettle responded to the banging of the pots. It began singing its song, and the water on the “bourgeois” instantly came to a boil. I grabbed the teapot and ran to the kitchen to rinse it.

In the kitchen, my face was greeted with cold air, and a wisp of steam appeared before my nose. The warmth from the “bourgeois” didn’t reach the kitchen, nor was it warmed by the gas stove. Cylinders placed in the metal booth outside conducted gas to the stove. They were delivered to the city irregularly, and there was often not enough gas, so one needed to conserve it. But even such a stove was a luxury in this house. Not so long ago, a very small kerosene stove would have been making noise in the kitchen.