Полная версия

Полная версияEverything Begins In Childhood

Translated into normal language, it meant: Grandpa possessed the health of a giant, an epic hero, “dev borin,” and that’s why he could tolerate everything we had been doing to him. Translated more precisely, it meant that Grandpa only pretended to be ill, that in point of fact, he was as healthy as a bull.

The massage was interrupted. We put on our slippers and headed for the door. Before we reached the door, we heard the powerful snoring of Grandpa, who had fallen asleep instantly.

Grandma, as if her statement had been fully corroborated, raised both hands to the sky and said again, “Dev borin!”

* * *Now, many years later, as I write these lines, I’m thinking: Grandma Lisa was essentially right, after all. My Grandpa Yoskhaim was an epic hero, in a certain sense.

Chapter 45. Dayenu!

Even now, when I hear a happy ringing exclamation at a Passover Seder, it seems to me that I don’t hear the voices of people at the table but rather the voices that I heard at my Grandpa Yoskhaim’s table many, many years ago.

“Da-a-yei-nu-u!”

Low men’s voices, soft melodious women’s voices, loud enthusiastic children’s voices seemed to merge into a common choir and become indistinguishable. But no, I recognize each of them.

The memories of my childhood – that’s what they are.

Grandpa’s bedroom had been transformed. It had become festive and smart. There were shiny glasses, rock crystal decanters, bottles and sparkling Passover dishes on the big table draped in a starched white tablecloth. The table had been brought here because the bedroom was bigger than the living room, and it was cozier with the stove, the ceiling finished in small wooden planks to create a nice pattern, and the antique carved furniture. Great-Grandpa, Grandma Lisa’s father, looked down at us from the photo on the chest of drawers, as if participating in the festivities.

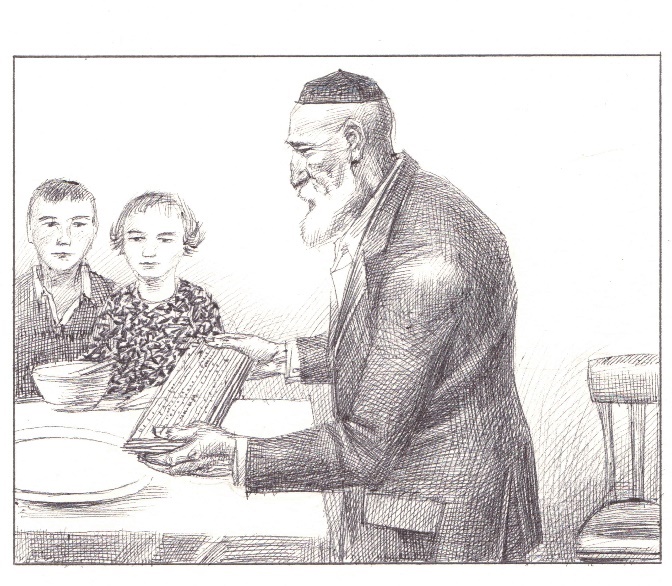

Grandpa Yoskhaim looked extremely smart in his starched snow-white shirt, black suit and black skull cap – a real patriarch with his gray beard. Only his rough fingers, disfigured by work, remained the same. But, perhaps, patriarchs had fingers like that.

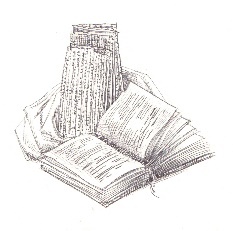

I see those twisted fingers carefully break a piece of matzo into two parts. It was the section in the middle of the three sections in front of him at the beginning of the Seder dinner. He broke one of the parts into small pieces and distributed them among us. We would eat them at the end of the dinner. The second section, called afikomen, had to be hidden where the kids couldn’t see it, for they would have to find it at the end of the festivities. The child who found it and hid it again was lucky: the head of the family would pay this child a ransom for the matzo. But in our family, even Grandpa didn’t quite remember that custom. That’s why only the second part of it was performed: the children hid the matzo. And Grandpa was busy with his principal task. After opening the Haggadah, the well-used book turned yellow and puffy from years of use, in which the rules for conducting a Seder were set forth in Hebrew and Russia, Grandpa began to read. If the rules had been strictly observed, we would all have had a copy of the Haggadah in our hands. But where could you get sacred books in our time? It was lucky that Grandpa had managed to preserve one copy. And we repeated our part after him… or pretended to.

The Passover Seder was accompanied by the solemn, singsong reading of prayers and blessings and the singing of psalms. Grandpa took pauses to give the necessary instructions to family members, to draw them into the festive ritual. Grandpa read the first prayer, waving the three pieces of matzo, which were now on the table in front of him, in his hand. Then he passed them to the youngest of us, Yura. Yura, almost without prompting, repeated the prayer. After him, it was my turn, and so on all around the table. Certainly, Grandpa knew everything he needed to read at Passover by heart. But one was expected to read from the Haggadah, and he didn’t tear his eyes from it.

Grandpa was reading and reading… And Yura and I, sitting at the other end of the table from Grandpa, squirmed on our chairs and kicked each other with our feet under the table. Our cousins also talked in whispers, kicked each other and giggled. The adults seemed not to strain their ears to hear the solemn words, they would rather have chatted and laughed with pleasure. They were more used to normal repasts than to the long and complex Passover ritual. Ilya, who sat next to Grandpa, even tried to turn a few pages of the Haggadah when Grandpa put it on the table. But could anyone throw Grandpa off? He remembered and saw everything, and he went back to the right part every time.

It’s not surprising that the Bukharan Jews had almost turned into Uzbeks. By a miracle, thanks to old men like Grandpa Yoskhaim and Grandpa Hanan, the majority of us preserved our faith. But the burden of everyday life, the absence of a strong religious community, and our Soviet upbringing gradually made the religious customs of our scattered people alien and incomprehensible to many of us.

There was one private teacher of Hebrew in the whole of Tashkent. Jewish culture was preserved under lock and key – no books, lectures or films about it were available. The adults at least knew something from their parents, but as for us children… Try to get a child to maintain a belief when at school they are constantly fed the idea that there is no God and that faith is savagery and obscurantism. Who cared that Grandpa uttered “the Almighty,” “Our Lord,” “Our Father in Heaven?” Why give thanks to someone who doesn’t exist and ask him for help? Did Grandpa really believe in supernatural forces? That was ridiculous. He was ignorant and uneducated.

However, something reconciled us to the Passover celebration. There were many activities in it that called for everyone’s participation. I began to understand the beauty of the rituals and their power to unite our people scattered throughout the world only when I became an adult. I think that the rituals were very clear to the Jews in the ancient times. They reminded them of real events that had happened not so long before. That’s why, most likely to make sure those events would stay in the memory of their descendants, they designed them in such detail, so that every small thing would serve as a landmark, a sign.

Yura, the youngest at the table, stood up and asked the family elder the four traditional questions – What makes this evening special? Why do we eat matzos? – and so on. That part of the Haggadah was called Ma Nishtana. Grandpa answered the questions, reading from the Haggadah. He told the story about the bitterness of Egyptian slavery (today it was symbolized by the bitter herb maror), and how the Angel of Death passed over the houses of Jews doomed to death (Pasakh in Hebrew) and how they had to escape with unleavened flatbread, matzos, for they had no time to leaven the dough. In a word, Grandpa presented the story of Exodus in brief as he answered Yura’s questions.

We all yelled joyfully and clearly, “Dayenu!” It was beautiful but incomprehensible. Perhaps Grandpa had explained its meaning, but I missed it. It means “It would have been enough.” The song of the Haggadah tells about the miracles performed by the Creator to get the Jews out of captivity. After each miracle is told, “It would have been enough” is proclaimed in unison. In other words, that one miracle would be enough for us to believe in His Power, even if we had failed to escape from Egypt.

* * *How do you like that? How briefly and, at the same time, with what power and nobleness, those who had written the Haggadah, expressed their gratitude to God.

The Seder dinner continued. Yura and I were pleased with it: the table was loaded with tasty food, including dishes we only got to eat once a year. And we didn’t deny ourselves anything. We ate fried chicken legs, hard-boiled eggs, fish, and the wonderfully rich tasty soup maso dyushak, chicken or meat broth with potatoes, fresh eggs, chopped herbs and small pieces of matzo added to it. M-m-m! Even now my mouth is watering.

Mama and Aunt Valya brought the soup to the table. They placed a deep bowl from which steam rose in front of each of us, and noisy eating immediately filled the air. Noisy eating was evidence of poor table manners, but the soup was too good to think about that. And Grandpa, who had grown tired and hungry, was making more noise that anybody else. His white beard disappeared into a thick cloud of steam, and only his nose and thick eyebrows could be seen.

Yura and I didn’t miss a thing. Now, we were busy with chaliko, ground nuts and raisins mixed with wine. Not bad, right? I heard that Jews in other countries called that dish charoset and made it of nuts and apples. Chaliko or charoset, that tasty paste, symbolized the clay that Jewish slaves in Egypt used to make bricks.

Yura handed the chaliko out to us himself. He put it between layers of matzo, adding lettuce leaves. He formed a big pie, broke it into pieces with the precision of a pharmacist and distributed them among the kids. He used twice as much chaliko for the two of us, which Yasha, who sat next to him, noticed. He was about to say something, but Yura directed a spoonful of chaliko toward his mouth, and Yasha decided not to expose him.

Not that I swallowed the chaliko; it disappeared in my mouth in a mysterious way, and I felt like having more right away. But prudence suggested: stop! There was so much of everything on the table. And how tempting was the luster of the bottles. Today, unlike on regular days, we were allowed to have a drink when our ancestors were remembered. And we managed to have another round in-between.

But then it became impossible to eat any more. Even Yura looked pensively and almost indifferently at the piles of food left on the table. And I saw that the adults had stopped eating. They had drinks, talked and laughed, drowning out Grandpa, though Mariya, Robert’s wife, was still eating. She had to eat more so there would be enough for two. Mariya had fixed her hair nicely and was well dressed, but her face was a little puffy and her belly protruded, tightening her silk blouse. It meant that another family member was at the table, this one not yet born.

Today, Mariya was merry. She looked peaceful, which didn’t happen often. The new daughter-in-law turned out to be a hard nut for Grandma Lisa to crack. Mariya became the first daughter-in-law who refused to tolerate Grandma’s escapades, reacting to them in a way Grandma wasn’t used to. First, Mariya never got scared and kept her cool when Grandma began to kick up a row. She, as they say, couldn’t care less. She didn’t give a damn about Grandma or the whole Yuabov family, including Robert. But if she lost her patience, she aired her grievances to her mother-in-law and husband. She packed her things and left for her mother’s a couple of times after serious rows. That was something unheard of. It was a great disgrace for a family in Central Asia. How could one possibly pretend that the family lived in peace and harmony after something like that happened?

In a word, Robert, who managed with difficulty to bring his wife back after she had left yet another time, forbade his mother to interfere in his family’s affairs. Grandma Lisa had to shut up as much as she could. She even had to put up with the fact that her youngest daughter-in-law refused to call her Mama.

Naturally, all the relatives, which was all of our families, knew how the youngest daughter-in-law behaved. But that wasn’t discussed because my father and Uncle Misha thought that Mariya set a bad example for their wives. Yes, Mariya aroused fear in them, and they snapped maliciously when she was the subject of conversation. By the way, Aunt Valya’s life had become easier because Grandma let up a bit after Mariya joined the family.

Aunt Valya, like my mama, was exhausted from rows and squabbles, but it was too much for her to struggle with her mother-in-law.

“How lucky you are that you were able to leave,” she said every time Mama came to Tashkent. She became very lonely after Mama left. She failed to become friends with the new daughter-in-law. Mama and Aunt Valya had always supported each other.

Mama came for Passover mostly for Valya’s sake. They sat across from me, also at the end of the table, so that it would be more convenient for them to get up and bring the hot food from the kitchen. They smiled at each other and talked quietly about something.

Mama was merry and beautiful. Her thick fluffy hair had been cut. Recently, she had broken her arm and had to wear a cast, so it was impossible for her to care for and set her long hair with one hand. She had had to get it cut, but it was very becoming on her.

Mama had dressed up and painted her eyebrows. She looked great, but her fingers and wrists were red and swollen. Our indefatigable mama, even though she had come to Tashkent for the holiday, had decided to earn some money. There were a few private bakeries in Tashkent that hired women to roll out and bake matzos before Passover, so Mama took a job at one of them, and she kneaded dough and rolled it out for twelve hours every day. At home, I had seen many times how it was done since pelmeni (dumplings) and manti (big dumplings) were made of exactly the same kind of dough. But at home it took her half an hour to make them, and here…

I always liked to watch Mama work. It seemed to me that she could do anything. And she made dough particularly well.

First, Mama mixed the dough in a pot or special small bucket. She kneaded the dough with her fist as if massaging it. She pressed, kneaded and mixed it. Her strong hand went through the dough almost to the bottom of the pot. She worked with concentration, breathing through her nose. When she took the ball of prepared dough out of the pot, it was soft, warm and springy, as if it were alive. Mama tossed it on her palm and patted it like a newborn. Then she put it on the table, covered in a layer of flour that looked like a diaper. Then, the “newborn” really suffered when she began to roll it.

First, she used a short thick rolling pin, then a long thin one that looked like a stick. Her hands slid between the center of the stick and its ends. Back and forth, back and forth went the rolling pin. Her hands continued to move between the center and the ends. The roll of dough became flat, getting thinner and thinner and wider, like a platter or tray. Mama picked it up by the edges and, with a precise movement, without tearing it, returned it to the table. It was almost transparent. It was about to break… But no, there wasn’t a single tear, not a single hole in its surface. You’d assume the dough was ready, right? Not at all. Mama splashed it with oil that she spread carefully over its surface and wrapped it around a rolling pin. Now, there was a long, rather thick rolling pin on the table. When Mama rolled the dough out the last time, it looked like a tablecloth. At last, the dough was ready to be used.

I saw all of that at home many times, and I never tired of admiring how beautifully Mama did it, how precisely, how skillfully. When a true master builds a house, creates a detail on a lathe or makes dough, that person can we considered an artist, if the work is done with talent. But I looked at the hands of my Mama, an artist, with pain and compassion that Passover evening. She had been kneading and rolling out dough for twelve hours, and now her swollen hands were on the table in front of her. They must have hurt.

Mama met my eyes and smiled at me tenderly and merrily, slightly raising the corners of her lips. I smiled at her in response and remembered that I had also had to work a bit before Passover, certainly not like Mama, but still…

Everybody, perhaps, knows that a Jewish home must not only be clean for Passover but spic and span. With housewives like my Grandma Lisa, pre-holiday cleaning becomes a disaster for the whole family. The walls, the windows, the floors and furniture must be cleaned and washed. Special dishes and kitchen utensils must be readied. There is no way to enumerate everything. Not a single member of the household can evade this “conscription” labor.

Even though it was my birthday on one of the pre-Passover days, that didn’t liberate me from boring housework. I was overwhelmed with resentment, but Grandma was implacable. “Djoni bivesh,” she said sweetly after I finished yet another assignment, “And now why don’t you do this.”

Among other things, I had to take down the tulle curtain, that very curtain behind which Grandma usually hid as she examined the yard. I stood on the chair near the window, trying to remove that damned curtain from under the cornice as Grandma sat nearby, her short legs slightly spread, moaning very mournfully, demonstrating how tired she was and, at the same time, watching my work vigilantly to prevent me from tearing the tulle, which was old but well preserved and beautiful. And the tulle actually was in danger. A nail was sticking out of the wall near the cornice, and either I had made a careless movement or something else had happened, but the tulle had gotten caught on the nail, and I couldn’t unhook it. It would be easy to pull it, but to unhook it without tearing it was not an easy thing to do. I was tense, I became confused, my hands grew numb, the chair creaked menacingly – it was Grandpa’s chair – every time I moved, but the curtain remained caught. At last, after performing an almost acrobatic maneuver and almost falling off the chair, I managed to get it off the nail.

“Djoni bivesh!” Even when Grandma praised me, she didn’t forget to remind me about her fatigue and suffering. Her eyes radiated all that with such expressiveness that it seemed she wouldn’t be able to get off the chair without help. As soon as I jumped to the floor with the curtain in my hands, Grandma said, in a businesslike manner:

“We’ll wash and dry everything today.” And she stood up, groaning.

I, by the way, very much enjoyed watching how the tulle was dried. Long, almost four-meter-wide wooden frames with hundreds of little nails attached to them were brought to the yard. The edges of the curtains were attached to them precisely, centimeter by centimeter. Tulle curtains dried this way ended up completely flat, as if they had just been bought. All the curtains in the house were usually washed once a year, before Passover. Our yard, filled with frames to which tulle curtains covered with floral designs and decorative patterns were attached, looked like an exhibition of folk art.

Now, Grandma’s curtain, looking younger and prettier, was back on the window as if participating in the festivities.

There was noisy and merry argument at the table.

“Where is it? Where’s the matzo?” Akhun yelled. “Haven’t you noticed? You gawkers!”

“I saw Yura go to the yard!” Ilya shouted.

“I most certainly did not!” Yura protested indignantly.

It seemed that this time he had nothing to do with it, but Yura had such a bad reputation that no one believed him.

“It was him! He did it! Let’s go to the yard!” Yasha continued to yell.

Dinner was over. The men got up, rattling the chairs. We all headed for the yard after each of us had picked up a white towel from where they were piled, one on top of another, on Grandpa’s bed. Grandpa continued to read the Haggadah loudly, as if giving his blessing to our feats.

Night had fallen while we had been feasting. The full moon lit our old yard in its spring splendor. Gentle pinkish flowers covered every branch of the apricot tree from top to bottom. The flowers on the upper branches got lost in the dark but shone eerily and enchantingly on the lower ones. A delicate intoxicating smell surrounded the tree like a cloud.

But we were not in the mood to admire flowers. Another Passover amusement was about to begin.

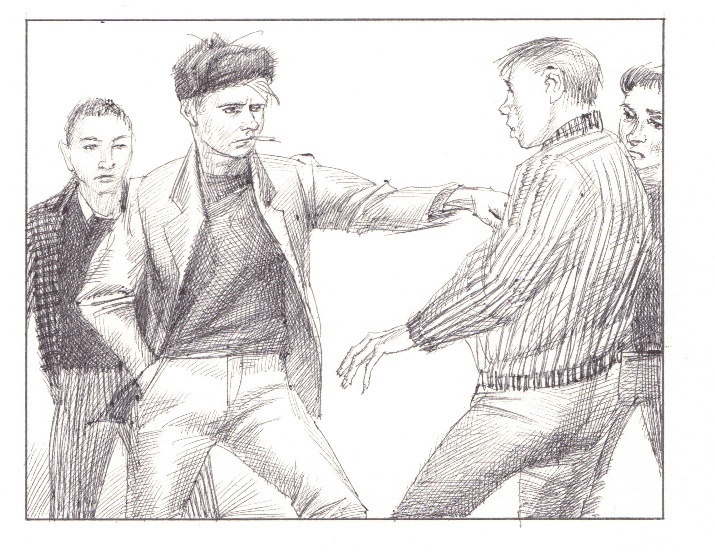

I don’t know how this custom, which isn’t mentioned in any of the canons, became a part of the festivities, but in our family, apparently just as in the families of other Bukharan Jews, the search for the afikoman turned into a battle between the adults and the children. Towels with a knot tied at the end served as our weapons.

“So, where did you hide it?” Ilya drew back his hand with the towel and whacked Yura on the back. Ilya was a strong guy, and a towel with a knot isn’t exactly a harmless weapon. Yura replied in kind. Akhun fought with Robert. I managed to smack Uncle Misha, but I also got it on the shoulders. We jumped up, ran from one place to another, yelled and laughed loudly. Our shadows rushed over the ground. The towels flashed in the moonlight. Yes, we were absolutely not like a peaceful urban family in those moments. We most likely resembled our ancient militant ancestors who had fought for their place under the sun.

“I found it! I found it!!” Yura’s ecstatic shout rang out. It turned out that it wasn’t he but Yasha who had hidden the matzo in the oven in the kitchen. Only Yura had the good sense to check there. The triumphant winner demanded a reward. Sweaty, excited and merry, we all burst into the house.

And there, in the bedroom, our patriarch with his gray beard continued reading the Haggadah loudly in a singsong voice to the empty table. It seemed that he hadn’t even noticed our leaving or coming back.

All the prayers of the first Seder had to be read to the end.

Chapter 46. Little Jew

Silence can absolutely be different. It’s not the same in the forest as it is in a field. It’s not the same at sea, even when it’s calm, as it is near a river. It is very special in the mountains and even in an empty apartment. Have you ever listened to the silence of a deserted school after classes?

I stood at the window in the corridor across from the door to our classroom. The long corridor ran into the distance, its polished floor shining. There was neither a soul nor a sound here or on the stairs.

Not a sound… The school was usually filled with the stomping of feet, shouts and laughter during recesses. Even when classes were in session, the loud voices of teachers, the hubbub of children’s voices, the creaking of desks could be heard from the corridor. A ball might be heard hitting the floor in the gym if basketball was being played there. If someone ran up the stairs, the footsteps were so resonant that they echoed in the corridor.

But now, stillness was everywhere. And I could hear it.

When neither noise nor rattling are heard, it doesn’t mean it’s actually quiet. Even stillness has its own voice, and it sounds different in different places. It’s not easy to describe.

Not that I could describe it then. I didn’t even think about it. I just stood there listening. And I felt good. I liked the school the way it was: silent, free from bustle, from nervous strain, from unpleasant anticipation, “Yuabov, to the blackboard!” It was as if the school were resting, and yet it enveloped me with something inimitably familiar.

I stood at the window, and the radiator sent warm air my way. Outside was the bitter freezing February weather with its penetrating wind. The snow in the schoolyard had frozen. It had almost become ice, trampled by hundreds of feet. All its unevenness, the rises and hollows, even the small area cleared of snow seemed like a degraded mountain landscape over which I had a bird’s eye view from the fourth-floor window. There were peaks, gorges and glens divided by a frozen river that cut through it all like a winding black ribbon.

Looking beyond that miniature landscape, I could see a truly boundless panorama: the outskirts of town and beyond them the road running toward the hills, to the spurs of the Tian Shan. Their snow-covered peaks, behind which the crimson ball of the sun was disappearing, stood out against the clear blue sky. It went down until only a small part of it, a crimson crescent, could be seen.

A tiny airplane suddenly rushed up toward the peaks, as if in pursuit of it. It had taken off from the military airdrome at the foot of the mountains. It seemed so small from here but was etched clearly against the sky with its sharp predatory nose. Perhaps it was a MIG-29, a new secret airplane. Such planes had begun to take off from the airdrome recently.