Полная версия

Полная версияEverything Begins In Childhood

The MIG shone in the rays of the setting sun for a couple of minutes. Then the sun disappeared, and the plane vanished…

Just in time I looked down and saw a familiar figure. She was Yulia Pavlovna Mekhreghina, our geography teacher, on her way to school.

We had geography club on Wednesdays. It was attended by a small group of students, just like other school clubs, but the members enjoyed it, including me and my friends Savchuk and Smirnov.

As Yulia Pavlovna, sniffling, took off her thick scarf and warmed her fingers, the members of the club gathered, all ten of us. Yulia Pavlovna sat on her desk, inviting us to feel at ease. And we did feel at ease, making ourselves comfortable at our desks. We could stand during club hours and behave as if we were at home. We didn’t have to wear school uniforms. We appreciated the relaxed atmosphere of our club gatherings very much.

“Shall we sail away? Then we’ll be looking for a Captain Grant. Who wants to be at the helm? You, Savchuk? Be my guest.”

Yulia Pavlovna moved to the edge of the desk to make room for a big globe. This globe was not new. It had been touched by so many not-quite-clean hands and was so threadbare that the names of the continents and oceans couldn’t always be distinguished. But that made it look like an old maritime map and created the illusion of being on a ship.

“All right… This is where we are now… The thirty-seventh parallel, South America… We’ve arrived at the shores of Chile.” Igor reported in a businesslike manner. “I’ve decided to leave the ship and set out for…” He buried his nose in the globe.

“Wait, wait! First look around. Who lives on the shore, what grows here? And in general…”

We grew animated at our desks. Someone leafed through a thick book; someone else walked to the teacher’s desk waving photographs.

We didn’t take quizzes here. We didn’t bring along notebooks with homework. We only brought what we were interested in, what we had found while searching through books and magazines. And we were interested in voyages, discoveries of new lands or, for instance, the Bermuda Triangle, or the magnetic storms of Antarctica…

Yulia Pavlovna, as I understand it now, was also a romantic. She enjoyed the travel game, wandering freely around the globe as much as we did, but she also had her little tricks, without which a talented teacher couldn’t manage.

“A question for all of you,” she again interrupted Savchuk, who was done with Chile and ready for a land journey. “If the Duncan approached the shores of Chile today…”

“The Chilean junta!” We yelled at the top of our lungs.

We knew that well for they trumpeted it on the radio, television and in newspapers. But the boring words “political system” were never pronounced. We, on our ship, simply got into a complex situation, and we discussed what might happen to us.

* * *Captain Grant’s search was successfully accomplished after two hours of a dangerous journey filled with adventures. Then we decided that we would explore the Juan Fernandez Islands, on one of which the famous Robinson Crusoe had found refuge.

Then, everybody went home. Only Gennady Herald and I stayed in the empty classroom. We were on duty today.

My classmate Gennady was an ethnic German. But that was not the reason he was famous in our school. He was famous as the younger brother of Sokura. The elder Herald brother – I don’t know how he got his nickname – was a dangerous guy who led a local gang. Stories were told about him as if he were a fierce legendary robber. For example, someone allegedly dared him to kill one of his pigeons. He didn’t hesitate and tore the pigeon’s head off. Then he smashed the mug of the guy who had challenged him. That’s the kind of person he was so, naturally, the younger Herald brother was also somewhat feared. Gennady was a poor student, often played hooky and, unlike us, didn’t attend the geography club out of a love of travel. He had become a club member for a short time, hoping to earn at least a C in geography.

Today, we were on duty together. “Students on duty,” as teachers preferred to call us, was somewhat too general. Simply and roughly speaking, we were janitors. And our work wasn’t easy.

There were three rows of desks – ten in each – thirty desks with heavy metal frames. They had to be stood on end, the trash swept out, and then they had to be put back. I was the first to lift the desks while Gennady handled a raggedy mop, keeping his legs apart like a peasant in a meadow mowing grass. Then we switched.

It wasn’t easy for me to lift the desks. It strained my back. It was even more difficult for Gennady, even though he was stronger than I, because he was short. But he didn’t show it was hard for him: he lifted desks and put them down as if he were lifting barbells.

When we had all the desks standing on end like soldiers at attention, I mopped and mopped the floor, wondering how all that trash could have accumulated in the classroom in just one day. Where could it have come from? Well, we had blotting paper fights, among other things.

It seemed we were finished.

We entered the corridor and looked outside. It was already dark. We saw a group of boys in the lit area. They were looking up, and as they saw me, they began to move and fuss. Someone pointed at me.

As I saw Kolya and Edem among them, I was glad: they must have come to pick me up. But then I remembered that I had had a falling out with them.

* * *Boys quarrel and make up all the time, everywhere and at all the ages. We were no exception. Kolya and Edem had been my friends for many years, but quarrels were an integral part of our relationship. We quarreled because of different trifling things during any game we played. We quarreled because we disagreed on different subjects, and an argument often ended in a fight, but we almost always made up right away. However, something had changed lately. When Kolya and I began to argue, his brother Sasha, along with Rustem with Edem, joined in our argument. They didn’t side with me; they always sided with Kolya. I was insulted and, at the same time, depressed: why was I always wrong? And a quarrel was insignificant, nothing to worry about. So, what was wrong? Sometimes, it was worse when Kolya’s father and mine quarreled, and the brothers stopped hanging around with me. But why did Rustem and Edem do it?

Of course, we would soon make up, usually without explaining anything. But that damned “why?” tortured me ever stronger. I lacked self-confidence and became suspicious. And one suspicion flashed through my mind more and more often: was it because I was a Jew?

Of course, I had heard at home that Jews were humiliated and persecuted all over the world. Even here, in Chirchik, they weren’t treated well enough. My parents and their friends discussed it quite often. I myself had heard offensive, burning words a few times. It wasn’t easy to forget them.

By the way, I also heard Tatar boys insulted quite a few times so ethnic intolerance wasn’t something abstract to me, but I didn’t expect it from my own friends… When such thoughts occurred to me, I considered them ridiculous and shameful, and I drove them away.

Last time, even though the quarrel was petty, it had ended in a malicious squabble. As I was leaving to go home, Kolya muttered, “Just you wait, we’ll deal with you!”

I paid no attention to it then; one could utter anything out of spite. But now, looking at Kolya and Edem surrounded by boys from Kolya’s class through the window, I remembered those words. Had they really come here to “deal” with me? Some friends they were…

I found it disgusting and, to be honest, rather scary.

“Are they waiting for you?”

I hadn’t noticed Gennady standing next to me also looking through the window. I didn’t want to answer and kept silent.

Herald slapped me on the shoulder.

“Don’t worry… Let’s go talk to them.”

The snow crunched under our feet. Gennady walked with his jacket unbuttoned and his cap cocked. A cigarette between his lips gave off smoke.

Taking long strides and pretending not to see anyone in front of him, he slammed right into the group of boys. Ready for a fight, I stood next to him.

“Who are you waiting for?”

One of the boys, the taller one, sneered and pointed at me:

“Little Jew.”

“Who, who?” Gennady asked. He moved close to the boy and exhaled cigarette smoke into his face. The boy shook his head.

“Well, c’mon… Who’s next?”

None of them moved. It was very quiet. Gennady, who wasn’t tall and was skinny, continued to smoke, shifting his eyes from one boy to another.

“Well…” Herald said. He dropped his cigarette, stomped it into the snow and jabbed that same boy who seemed to be the leader of the group in the chest.

“Would you like to be a pigeon?”

Deathly silence was the answer. They must have heard about the fate of Sokura’s pigeon.

Gennady kept silent a while. Then he spat at the boy’s feet.

“Valery, if anyone bothers you, let me know. Let’s go!”

And we left the schoolyard without looking back.

* * *Kolya, Edem and I, naturally, made up shortly after that. I don’t remember how.

Chapter 47. Boolk-Boolk, or the Day of Delicious Food

“Where’s that damned jar? Perhaps on another shelf?”

I stood on a chair near the shelves on the veranda, hunched up against the winter morning cold, looking for a jar without a lid among the home-canned foods. While my eyes were searching, my imagination continued to draw a different picture, devised during the night.

This quiet winter night, when our whole building, like the whole Yubileyny Settlement, like all of Chirchik, was fast asleep, a deafening rumble was heard… It woke me up, but not quite; rather it was woven into my sleepy dreams. “They’re shooting…It’s war… No, shooting is coming from the tank school where a training exercise is underway.” And then I envisioned a cadet, a tank operator. He must have been dozing in his tank, just like me in my bed. Being only half-awake, he confused north and south and, instead of shooting at the bare hills, shot at the residential area. And a projectile hit our yard and exploded with a crash. I would check in the morning how many windowpanes had been broken.

To tell the truth, these dreams didn’t crop up for the first time this night. My friends and I had imagined that many times, but under much more dramatic circumstances. A projectile hit the building, a fire broke out, moans and shouts were heard, sirens wailed – ambulance, police, firetrucks… Water spurted from hoses. And we boys didn’t panic; we hastened to rescue the wounded. We made our way up the stairs through thick smoke; we knocked down apartment doors and, groping our way, looked for helpless suffocating people in the chaos of smoke and flames and carried them outside on our shoulders.

By the way, I think many adult residents of our town had pondered the possibility of such an accident, without dreaming at all about heroic feats.

Even though I was lost in my dreams, my eyes continued their work, and, at last, the true protagonist of the night’s rumble was found: a jar without a lid. It was absolutely not “the damned jar,” as Mama had called it when she sent me to find it. My attitude toward the jar was much more benevolent, and I didn’t blame it for anything. On the contrary, it looked like a normal jar filled with cherry preserves, which were very tasty though a bit sour. I was going to check it now.

It is quite possible to use one’s finger in emergencies. That’s what I did. I absolutely didn’t need a spoon. It was even tastier with a finger. Adults pretend not to understand that, “How can you do that with your finger? It’s outrageous!” Didn’t they do it when they were kids?

Standing on the chair, hugging the cold jar of preserves, continuing my pleasant occupation, I looked through the window. The sweet stuff warmed me up, and I felt very good.

The day was breaking. In the morning light, I saw what one didn’t often get a chance to admire in our parts because a cold snowy winter in Uzbekistan was a rarity. It hadn’t been cold yesterday. Snow fell, was damp and began to melt. But suddenly, intensely cold weather hit, and all the shrubs and trees turned into icy sculptures covered with a hard, transparent crust. Thin trees bent under it. Did it hurt? I didn’t know, but it was so beautiful. As soon as the sun rose, each branch would begin to glisten, to sparkle with little multicolored iridescent lights as if it were studded with gems.

* * *One shouldn’t eat too much of a good thing, there was considerably less left in the jar now. As I was about to get down from the chair, I spied the handle of a small suitcase sticking out on the upper shelf. I remembered that the suitcase had been sitting on the shelf since we moved to Chirchik. I had meant to check what was in it long ago, but then I forgot about it.

Mama wasn’t yet in the kitchen. Father was on a business trip. I put a small stool on the chair, climbed onto it and pulled the suitcase down carefully. I sat down with the suitcase on the floor, which was wooden but still cold. Opening the tight locks and lifting the cover, I felt like a treasure hunter, my heart was in my throat.

And not for nothing. Something multicolored shone under the cover as if the suitcase were filled with precious stones. Wow, they were so big!

But the happy illusion lasted only a second. There were not stones but rather strange glass objects in the suitcase. They were red, yellow, greenish, transparent, some of them straight and short, others intricately bent, and all of them wide at one of the ends. In a word, they were unusual tubes, and I understood a moment later what kind of tubes they were when I saw a small bottle with a rubber thing, something like a child’s enema bag, attached to its side. Ah, those were Father’s tubes for aerosol which he had used long ago when he had asthma attacks. The tubes had to be attached to a bottle of aerosol and put into his mouth. I didn’t remember how to attach the tubes, but I decided to try.

I picked out one of the more interesting tubes and began to insert it into the neck of the bottle. Crack! “Ah, how clumsy I am!” A fragment of glass cut into my finger. The cut was bad, and I had to run to get iodine and a bandage.

* * *When I returned, I began hiding the fragments on the bottom of the suitcase and was about to put it back onto the shelf: it had nothing to do with me. The edge of a bright book jacket flashed at the bottom of the suitcase, and the aficionado of reading turned out to be stronger than the petty coward. It was strange to find the novels “Runaway” and “Rebels of the Gold Fields” by Jack Lindsay instead of books on basketball in Father’s suitcase. Well, I couldn’t deny myself the pleasure of reading them. The suitcase returned to the upper shelf without the books.

“Are you still here? Without a sweater? Immediately…”

That was Mama. She peeked into the veranda from the kitchen as she was tying up her apron. Closing the cupboard and putting the chair back in its place, I could hear “Mama” sounds that were so pleasant and habitual: water running from the faucet, the striking of a match, the clanking of dishes.

“What do you want for breakfast?”

“Eggs Boolk-boolk,” I answered right away.

Eggs cooked according to Mama’s method were considered one of the best family delicacies.

“All right. Then wake Emma up quickly.” Oh, well… The most interesting part was about to begin, something I could watch a hundred times, and here “wake up Emma” interfered.

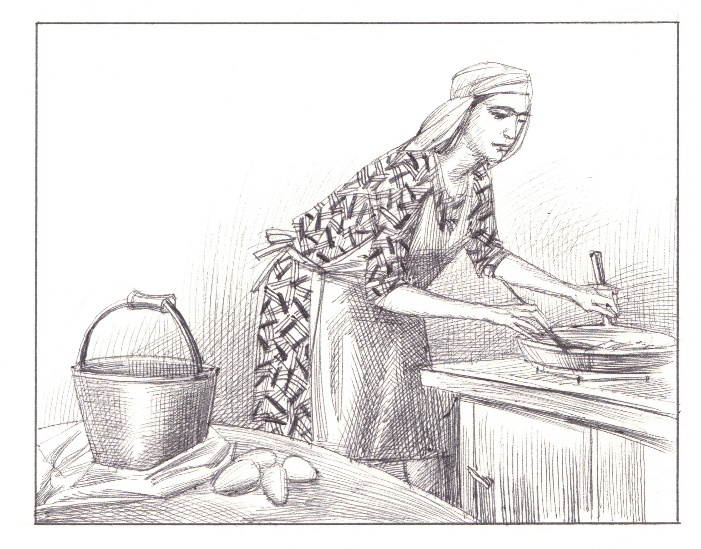

I rushed into the bedroom and shook my sleeping sister, “Eggs Boolk-boolk are for breakfast! Hurry, or I’ll eat them myself!” And I rushed out as quickly as I had rushed in. I knew that was enough for Emma to jump out of bed: she liked Boolk-boolk as much as I did, and she always feared my treachery. As I was running out of the bedroom, I heard Emma yelp and jump out of bed. Meanwhile, Mama got the little old cast iron cauldron with the flat bottom and the handles that stuck out like ears and rinsed it. That cauldron, old and safe, had served us for many years. She dried it, put it on the stove and poured cotton oil generously into it. She struck a match, and bluish tongues of flame began to lick greedily at the cauldron. While it grew red-hot, while the oil was heating, Mama quickly and skillfully sliced an onion and distributed it among three plates. The oil had already become hot enough; Mama knew exactly when it happened. And at that moment, Mama cracked an egg against the edge of the stove and, after separating the halves of its shell, poured the egg very slowly into the oil. Just one egg since each serving of Boolk-boolk had to be cooked separately.

Now, it was time to watch the cooking egg uninterrupted. Psh-sh, the oil began to boil in the cauldron. The egg dived into the oil. It sank to the bottom and began to dance a little in that transparent oil lake, or rather ocean, because the egg had turned into a jellyfish with a yellow eye. Its colorless body was turning white like the train of a wedding gown, bubbles forming on its surface. And the yellow eye could be seen rising to the surface over and over again.

Mama picked up the kafkir – that’s what we called a spatula in our parts – and, holding the cauldron by the handle, began to splash hot oil over the egg, wave by wave.

Boolk-boolk-boolk. One, two, three… That’s how that sound became the name of our favorite dish. It was accompanied by muted dzing… dzing… dzing, the singing of the cauldron when its sides were hit by the spatula. I’m sorry for those who have never heard this wonderful concert.

And what had become of the jellyfish’s yellow eye? It was being covered by a thin whitish layer that resembled a walleye. The layer, at first thin, become thicker and thicker after each wave of oil. The formerly yellow eye bulged, round and bright white.

That was it. The Boolk-boolk was ready. Mama moistened a piece of matzo with water and put it on each plate under the onions. A Boolk-boolk was planted on top of the onions. It was smooth and snowy white, without a single brown spot, definitely not overdone.

Emma was the first to receive one. As you might have guessed, she had long ago shown up and was sitting at the table. She grabbed the plate, casting a triumphant glace at me: you hoped to eat my serving for no reason.

“All right,” I thought. “Are you putting on airs? You’ll get your just reward…”

“Have you washed your hands?” I asked with the most innocent intonation.

Mama would absolutely not allow us to eat with dirty hands. She looked at Emma sternly.

“I… I rinsed them,” Emma began to whine, drying her hands against her dress.

Mama drew her eyebrows together to demonstrate that she was very upset, and my sister, her lower lip stuck out to demonstrate how hurt she was, rushed to the bathroom. Mama grinned and began to cook another Boolk-boolk. Here it was on my plate, and the third one – on Mama’s.

It was a pity to touch such a perfect thing, perhaps because I had seen how it had emerged. I felt I took part in its creation. But I was also very hungry. I picked up a piece of matzo, pierced the top of the glossy white knoll, and yellow lava immediately covered it.

All we could hear for a few minutes was the tapping of forks and the way Emma, covered with egg yolk, munched. At last, she ate the last piece and asked for a second helping. But the little cauldron had already cooled off, and Mama shook her head:

“Have some lavz.” She uncovered a soup bowl and we saw diamond-shaped, extremely tasty pieces of Eastern sweets: bits of nuts cooked in honey with some flour added. “I was treated to it at work yesterday. You kids eat it.”

She didn’t need to ask us twice.

Emma grabbed a piece of lavz with incomprehensible speed. She also managed to single out the largest diamond. Emma had a sweet tooth, but lavz evoked special feelings in her. And Emma’s feelings, particularly the intense ones, were immediately reflected in her little face: her hazel eyes lit up; there was a happy smile on her lips even though she was still chewing; her cheeks grew pink; her fluffy short hair – it might only have seemed to me – became even fluffier. Why? Who knows? Was it possible that her temperature went up from delight, and the fever that enveloped her stood her hair on end?

As for the lavz, it seemed to me to have special gustatory qualities that affected not only children but also adults. I used to watch venerable guests devour it with pleasure at weddings, and I thought that, perhaps, the person who had invented lavz had created it to give adults their childhood back, if only for a moment.

The lavz Mama had been treated to was very good, soft and fragrant. Mama and I also picked up a diamond each. Mama bit tiny pieces off slowly. She leaned back on the chair, with the tea bowl in her right hand. A cloud of steam rose to her calm gentle face. We hardly ever saw Mama relaxing, doing nothing, simply watching her kids feasting on something delicious.

But Mama couldn’t relax for a very long.

“What would you like for dinner?” she asked looking at the chewing Emma.

“Bakhsh!” Emma blurted out as if she had prepared the answer in advance. Fortunately, our tastes were the same. “In a bag,” I specified. “Can you do it, Mama?” “Today is my day off. Why not?” Mama smiled. “All right, let’s sort through the rice.”

Bakhsh is a type of pilaf, to be precise it’s a relative of pilaf whose taste and color differ from other pilafs. It’s also made with rice and meat, though without carrots, and it’s cooked in a cauldron or… I’ll describe the second way of making it as I remember it.

* * *We put away the dishes quickly. I wiped the table. It was smooth and white, and it was a pleasure to sort rice or any other grain on it. Mama brought the can in which we stored the rice and emptied two full bowls of it onto the table. That was enough for two dinners for three of us.

I don’t know if it’s possible to turn any boring occupation into pleasure, but Mama usually managed to do it. As we sat down to sort the rice, we became three players and a competition began: who could sort more. Not only the amount of rice, but also the amount of debris was taken into account. Certainly, Mama was a much stronger player, but Emma and I were given the advantage of competing as a team.

Each of us separated some rice from the pile with one hand, enough to cover a part of the table in front of us with a thin layer. Mama did it amazingly gently and gracefully.

As soon as the white rice was laid out on the white table, all the dark specks stood out clearly: tiny pebbles, bits of dirt, rotten rice grains – all of those we were supposed to hunt.

Emma and I rushed, but our clumsy fingers didn’t always hit the right spot, we didn’t always manage to remove a pebble, husk or something else without taking along a clean grain of rice. We cast jealous glances at Mama who had already removed a lot of debris. How could her fingers move so fast and always to the right spot?

No matter how fast we tried to do it, no matter how slowly Mama tried to do it, we finished our work at the same time. Yes, we finished it at the same time, if one ignored the results.

Mama checked our work very carefully, without hurting us. With laughter and jokes, she removed quite a few specks from the rice we had sorted out and, from the debris, some clean rice that had got there accidentally. Mama hated to waste good things.

At last, all the rice went into a lagancha, a deep metal bowl, and was covered with water. Then Mama cut meat on a cutting board into such thin slices that the knife didn’t seem to move at all but rather to be cutting off the same slice over and over. However, the big piece of meat was getting smaller and smaller until, at last, the pile of slices was salted and moved to the bowl of rice from which Mama had drained the water, which we hadn’t even noticed her do. It seemed to me that Mama was a magician. How had a can of cilantro gotten into her hands? The cilantro was dried, of course. Mama would buy cilantro along with other herbs and other herbs at the bazaar in summer. She would buy a lot of it so that we would have enough throughout the winter. The herbs were dried on the veranda, filling it with their scent. But even now, when Mama opened the can and put dried cilantro over rice and meat, I could smell a delicate, pleasant, exciting aroma that reminded me of summer.