Полная версия:

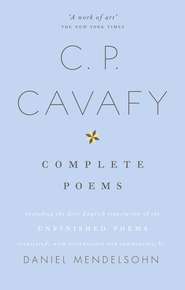

The Complete Poems of C.P. Cavafy

[1910; 1911]

As Much As You Can

And even if you cannot make your life the way you want it,

this much, at least, try to do

as much as you can: don’t cheapen it

with too much intercourse with society,

with too much movement and conversation.

Don’t cheapen it by taking it about,

making the rounds with it, exposing it

to the everyday inanity

of relations and connections,

so it becomes like a stranger, burdensome.

[1905; 1913]

Trojans

Our efforts, those of the ill-fortuned;

our efforts are the efforts of the Trojans.

We will make a bit of progress; we will start

to pick ourselves up a bit; and we’ll begin

to be intrepid, and to have some hope.

But something always comes up, and stops us cold.

In the trench in front of us Achilles

emerges, and affrights us with his shouting.—

Our efforts are the efforts of the Trojans.

We imagine that with resolve and daring

we will reverse the animosity of fortune,

and so we take our stand outside, to fight.

But whenever the crucial moment comes,

our boldness and our daring disappear;

our spirit is shattered, comes unstrung;

and we scramble all around the walls

seeking in our flight to save ourselves.

And yet our fall is certain. Up above,

on the walls, already the lament has begun.

They mourn the memory, the sensibility, of our days.

Bitterly Priam and Hecuba mourn for us.

[1900; 1905]

King Demetrius

Not like a king, but like an actor, he exchanged his showy robe of state for a dark cloak, and in secret stole away.

—PLUTARCH, Life of Demetrius

When the Macedonians deserted him,

and made it clear that it was Pyrrhus they preferred

King Demetrius (who had a noble

soul) did not—so they said—

behave at all like a king. He went

and cast off his golden clothes,

and flung off his shoes

of richest purple. In simple clothes

he dressed himself quickly and left:

doing just as an actor does

who, when the performance is over,

changes his attire and departs.

[1900; 1906]

The Glory of the Ptolemies

I’m the Lagid, a king. The possessor absolute

(with my power and my riches) of pleasure.

There’s no Macedonian, no Eastern foreigner

who’s my equal, who even comes close. What

a joke, that Seleucid with his vulgar luxe.

But if there’s something more you seek, then simply look:

the City is our teacher, the acme of what is Greek,

of every discipline, of every art the peak.

[1896; 1911; 1911]

The Retinue of Dionysus

Damon the artisan (none as fine

as he in the Peloponnese) is

fashioning the Retinue of Dionysus

in Parian marble. The god in his divine

glory leads, with vigor in his stride.

Intemperance behind. Beside

Intemperance, Intoxication pours the Satyrs wine

from an amphora that they’ve garlanded with vines.

Near them delicate Sweetwine, his eyes

half-closed, mesmerizes.

And further down there come the singers,

Song and Melody, and Festival

who never allows the hallowed processional

torch that he holds to go out. Then, most modest, Ritual.—

That’s what Damon is making. Along with all

of that, from time to time he gets to pondering

the fee he’ll be receiving from the king

of Syracuse, three talents, quite a lot.

When that’s added to the money that he’s got,

he’ll be well-to-do, will lead a life of leisure,

can get involved in politics—what pleasure!—

he too in the Council, he too in the Agora.

[1903; 1907]

The Battle of Magnesia

He’s lost his former dash, his pluck.

His wearied body, very nearly sick,

will henceforth be his chief concern. The days

that he has left, he’ll spend without a care. Or so says

Philip, at least. Tonight he’ll play at dice.

He has an urge to enjoy himself. Do place

lots of roses on the table. And what if

Antiochus at Magnesia came to grief?

They say his glorious army lies mostly ruined.

Perhaps they’ve overstated: it can’t all be true.

Let’s hope not. For though they were the enemy, they were kin to us.

Still, one “let’s hope not” is enough. Perhaps too much.

Philip, of course, won’t postpone the celebration.

However much his life has become one great exhaustion

a boon remains: he hasn’t lost a single memory.

He remembers how they mourned in Syria, the agony

they felt, when Macedonia their motherland was smashed to bits.—

Let the feast begin. Slaves: the music, the lights!

[1913; 1916]

The Seleucid’s Displeasure

The Seleucid Demetrius was displeased

to learn that a Ptolemy had arrived

in Italy in such a sorry state.

With only three or four slaves;

dressed like a pauper, and on foot. This is why

their name would soon be bandied as a joke,

an object of fun in Rome. That they have, at bottom,

become the servants of the Romans, in a way,

the Seleucid knows; and that those people give

and take away their thrones

arbitrarily, however they like, he knows.

But nonetheless at least in their appearance

they should maintain a certain magnificence;

shouldn’t forget that they are still kings,

that they are still (alas!) called kings.

This is why Demetrius the Seleucid was annoyed,

and straightaway he offered Ptolemy

robes all of purple, a gleaming diadem,

exceedingly costly jewels, and numerous

servants and a retinue, his most expensive mounts,

that he should appear in Rome as was befitting,

like an Alexandrian Greek monarch.

But the Lagid, who had come a mendicant,

knew his business and refused it all;

he didn’t need these luxuries at all.

Dressed in worn old clothes, he humbly entered Rome,

and found lodgings with a minor craftsman.

And then he presented himself to the Senate

as an ill-fortuned and impoverished man,

that with greater success he might beg.

[1910; 1916]

Orophernes

He, who on the four-drachma piece

seems to have a smile on his face,

on his beautiful, refined face,

he is Orophernes, son of Ariarathes.

A child, they chased him out of Cappadocia,

from the great ancestral palace,

and sent him away to grow up

in Ionia, to be forgotten among foreigners.

Ah, the exquisite nights of Ionia

when fearlessly, and completely as a Greek,

he came to know pleasure utterly.

In his heart, an Asiatic still:

but in his manners and in his speech a Greek,

bedecked with turquoise, yet Greek-attired,

his body scented with perfume of jasmine;

and of Ionia’s beautiful young men

the most beautiful was he, the most ideal.

Later on, when the Syrians came

to Cappadocia, and had made him king,

he threw himself completely into his reign,

that he might enjoy some novel pleasure each new day,

that he might horde the gold and silver, avaricious,

that over all of this he might exult, and gloat

to see the heaped-up riches glittering.

As for cares of state, administration—

he didn’t know what was going on around him.

The Cappadocians quickly threw him out.

And so to Syria he fled, to the palace of

Demetrius, to entertain himself and loll about.

Still, one day some unaccustomed thoughts

broke in on his total idleness:

he remembered that through his mother, Antiochis,

and through that ancient lady, Stratonice,

he too descended from the Syrian crown,

he too was very nearly a Seleucid.

For a while he emerged from his lechery and drink,

and ineptly, in a kind of daze,

cast around for something he might plot,

something he might do, something to plan,

and failed miserably and came to nothing.

His death must have been recorded somewhere and then lost.

Or maybe history passed it by,

and very rightly didn’t deign

to notice such a trivial thing.

He, who on the four-drachma piece

left the charm of his lovely youth,

a glimmer of his poetic beauty,

a sensitive memento of an Ionian boy,

he is Orophernes, son of Ariarathes.

[1904; 1916]

Alexandrian Kings

The Alexandrians came out in droves

to have a look at Cleopatra’s children:

Caesarion, and also his little brothers,

Alexander and Ptolemy, who for the first

time were being taken to the Gymnasium,

that they might proclaim them kings

before the brilliant ranks of soldiers.

Alexander: they declared him king

of Armenia, of Media, of the Parthians.

Ptolemy: they declared him king

of Cilicia, of Syria, of Phoenicia.

Caesarion was standing well in front,

attired in rose-colored silk,

on his chest a garland of hyacinths,

his belt a double row of sapphires and amethysts,

his shoes laced up with white

ribbons embroidered with pink-skinned pearls.

Him they declared greater than the boys:

him they declared King of Kings.

The Alexandrians were certainly aware

that these were merely words, a bit of theatre.

But the day was warm and poetic, the sky pale blue,

the Alexandrian Gymnasium

a triumphant artistic achievement,

the courtiers’ elegance exceptional,

Caesarion all grace and beauty

(Cleopatra’s son, of Lagid blood):

and the Alexandrians rushed to the festival,

filled with excitement, and shouted acclaim

in Greek, and in Egyptian, and some in Hebrew,

enchanted by the lovely spectacle—

though of course they knew what they were worth,

what empty words these kingdoms were.

[1912; 1912]

Philhellene

Take care the engraving’s artistically done.

Expression grave and majestic.

The diadem better rather narrow;

I don’t care for those wide ones, the Parthian kind.

The inscription, as usual, in Greek:

nothing excessive, nothing grandiose—

the proconsul mustn’t get the wrong idea,

he sniffs out everything and reports it back to Rome—

but of course it should still do me credit.

Something really choice on the other side:

some lovely discus-thrower lad.

Above all, I urge you, see to it

(Sithaspes, by the god, don’t let them forget)

that after the “King” and the “Savior”

the engraving should read, in elegant letters, “Philhellene.”

Now don’t start in on me with your quips,

your “Where are the Greeks?” and “What’s Greek

here, behind the Zágros, beyond Phráata?”

Many, many others, more oriental than ourselves,

write it, and so we’ll write it too.

And after all, don’t forget that now and then

sophists come to us from Syria,

and versifiers, and other devotees of puffery.

Hence unhellenised we are not, I rather think.

[1906; 1912]

The Steps

On an ebony bed that is adorned

with eagles made of coral, Nero sleeps

deeply—heedless, calm, and happy;

flush in the prime of the flesh,

and in the beautiful vigor of youth.

But in the alabaster hall that holds

the ancient shrine of the Ahenobarbi

how uneasy are his Lares!

The little household gods are trembling,

trying to hide their slight bodies.

For they’ve heard a ghastly sound,

a fatal sound mounting the stairs,

footsteps of iron that rattle the steps.

And, faint with fear now, the pathetic Lares,

wriggle their way to the back of the shrine;

each jostles the other and stumbles

each little god falls over the other

because they’ve understood what kind of sound it is,

have come to know by now the Erinyes’ footsteps.

[1893; 1897; 1903; 1909]

Herodes Atticus

Ah, Herodes Atticus, what glory is his!

Alexander of Seleucia, one of our better sophists,

on arriving in Athens to lecture,

finds the city deserted, since Herodes was

away in the country. And all of the young people

followed him out there to hear him.

So Alexander the sophist

writes Herodes a letter

requesting that he send back the Greeks.

And smooth Herodes swiftly responds,

“I too am coming, along with the Greeks.”

How many lads in Alexandria now,

in Antioch, or in Beirut

(tomorrow’s orators, trained by Greek culture)

when they gather at choice dinner parties

where sometimes the talk is of fine intellectual points,

and sometimes about their exquisite amours,

suddenly, abstracted, fall silent.

They leave their glasses untouched at their sides,

and they ponder the luck of Herodes—

what other sophist was honored like this?—

whatever he wants and whatever he does

the Greeks (the Greeks!) follow him,

neither to criticize nor to debate,

nor even to choose any more; just to follow.

[1900; 1911; 1912]

Sculptor from Tyana

As you will have heard, I’m no beginner.

Lots of stone has passed between my hands.

And in Tyana, my native land,

they know me well. And here the senators

commission many statues.

Let me show

a few to you right now. Notice this Rhea;

august, all fortitude, quite archaic.

Notice the Pompey. The Marius,

the Aemilius Paullus, and the African Scipio.

The likenesses, as much as I was able, are true.

The Patroclus (I’ll touch him up soon).

Near those pieces of yellowish

marble there, that’s Caesarion.

And for some time now I’ve been involved

in making a Poseidon. Most of all

I’m studying his horses: how to mold them.

They must be rendered so delicately that

it will be clear from their bodies, their feet,

that they aren’t treading earth, but racing on water.

But this work here is my favorite of all,

which I made with the greatest care and deep feeling:

him, one warm day in summer

when my thoughts were ascending to ideal things,

him I stood dreaming here, the young Hermes.

[1893; 1903; 1911]

The Tomb of Lysias the Grammarian

Just there, on the right as you go in,

in the Beirut library we buried him:

the scholar Lysias, a grammarian.

The location suits him beautifully.

We put him near the things that he

remembers maybe even there—glosses, texts,

apparatuses, variants, the multivolume works

of scholarship on Greek idiom. Also, like this,

his tomb will be seen and honored by us

as we pass by on our way to the books.

[1911; 1914]

Tomb of Eurion

Inside of this elaborate memorial,

made entirely of syenite stone,

which so many violets, so many lilies adorn,

Eurion lies buried, so beautiful.

A boy of twenty-five, an Alexandrian.

Through the father’s kin, old Macedonian;

a line of alabarchs on his mother’s side.

With Aristoclitus he took his philosophical instruction;

rhetoric with Parus. A student in Thebes, he read

the sacred writings. He wrote a history

of the Arsinoïte district. This at least will endure.

Nevertheless we’ve lost what was most dear: his beauty,

which was like an Apollonian vision.

[1912; 1914]

That Is He

Unknown, the Edessene—a stranger here in Antioch—

writes a lot. And there, at last, the final canto has

appeared. Altogether that makes eighty-three

poems in all. But the poet is worn out

from so much writing, so much versifying,

the terrific strain of so much Greek phrasing,

and every little thing now weighs him down.

A sudden thought, however, pulls him out

of his dejection—the exquisite “That is he”

which Lucian once heard in a dream.

[1898; 1909]

Dangerous

Said Myrtias (a Syrian student

in Alexandria; during the reign

of the augustus Constans and the augustus Constantius;

partly pagan, and partly Christianized):

“Strengthened by contemplation and study,

I will not fear my passions like a coward.

My body I will give to pleasures,

to diversions that I’ve dreamed of,

to the most daring erotic desires,

to the lustful impulses of my blood, without

any fear at all, for whenever I will—

and I will have the will, strengthened

as I’ll be with contemplation and study—

at the crucial moments I’ll recover

my spirit as it was before: ascetic.”

[?; 1911]

Manuel Comnenus

The emperor Lord Manuel Comnenus

one melancholy morning in September

sensed that death was near. The court astrologers

(those who were paid) were nattering on

that he had many years left yet to live.

But while they went on talking, the king

recalls neglected habits of piety,

and from the monastery cells he orders

ecclesiastical vestments to be brought,

and he puts them on, and is delighted

to present the decorous mien of a priest or friar.

Happy are all who believe,

and who, like the emperor Lord Manuel, expire

outfitted most decorously in their faith.

[1905; 1916]

In the Church

I love the church—its labara,

the silver of its vessels, its candelabra,

the lights, its icons, its lectern.

When I enter there, inside of a Greek Church:

with the aromas of its incenses,

the liturgical chanting and harmonies,

the magnificent appearance of the priests,

and the rhythm of their every movement—

resplendent in their ornate vestments—

my thoughts turn to the great glories of our race,

to our Byzantium, illustrious.

[1892; 1901; 1906; 1912?]

Very Rarely

He’s an old man. Worn out and stooped,

crippled by years, and by excess,

stepping slowly, he moves along the alleyway.

But when he goes inside his house to hide

his pitiful state, and his old age, he considers

the share that he—he—still has in youth.

Youths recite his verses now.

His visions pass before their animated eyes.

Their healthy, sensuous minds,

their well-limned, solid flesh,

stir to his own expression of the beautiful.

[1911; 1913]

In Stock

He wrapped them up carefully, neatly

in green silken cloth, very costly.

Roses from rubies, pearls into lilies,

amethyst violets. Lovely the way that he sees,

and judges, and wanted them; not in the way

he saw them in nature, or studied them. He’ll put them away,

in the safe: a sample of his daring, skillful work.

Whenever a customer comes into the store,

he takes other jewels from the cases to sell—fabulous things—

bracelets, chains, necklaces, rings.

[1912; 1913]

Painted

To my craft I am attentive, and I love it.

But today I’m discouraged by the slow pace of the work.

My mood depends upon the day. It looks

increasingly dark. Constantly windy and raining.

What I long for is to see, and not to speak.

In this painting, now, I’m gazing at

a lovely boy who’s lain down near a spring;

it could be that he’s worn himself out from running.

What a lovely boy; what a divine afternoon

has caught him and put him to sleep.—

Like this, for some time, I sit and gaze.

And once again, in art, I recover from creating it.

[1914; 1916]

Morning Sea

Here let me stop. Let me too look at Nature for a while.

The morning sea and cloudless sky

a brilliant blue, the yellow shore; all

beautiful and grand in the light.

Here let me stop. Let me fool myself: that these are what I see

(I really saw them for a moment when I first stopped)

instead of seeing, even here, my fantasies,

my recollections, the ikons of pleasure.

[?; 1916]

Song of Ionia

Because we smashed their statues all to pieces,

because we chased them from their temples—

this hardly means the gods have died.

O land of Ionia, they love you still,

it’s you whom their souls remember still.

And as an August morning’s light breaks over you

your atmosphere grows vivid with their living.

And occasionally an ethereal ephebe’s form,

indeterminate, stepping swiftly,

makes its way along your crested hills.

[1891; 1896; 1905; 1911]

In the Entrance of the Café

Something they were saying close to me

drew my attention to the entrance of the café.

And I saw the lovely body that looked as if

Eros had made it using all his vast experience: