Полная версия:

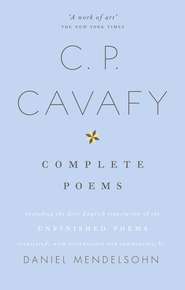

The Complete Poems of C.P. Cavafy

the shops, the pavements, the stones,

and walls, and balconies, and windows;

there was nothing ugly that remained there.

And while I was standing, gazing at the door,

and standing, tarrying by the house,

the foundation of all my being yielded up

the sensual emotion that was stored inside.

[1917; 1919]

The Next Table

Can’t be more than twenty-two years old.

And yet I’m sure that, just about the same

number of years ago, I enjoyed that very body.

It’s not at all a flaring of desire.

And I only came to the casino a little while ago;

I haven’t even had time to drink a lot.

This very body: I enjoyed it.

And if I don’t remember where—one slip doesn’t signify.

Ah there, sitting at the next table now:

I recognize each movement—and beneath the clothes

I see once more the naked limbs I loved.

[1918; 1919?]

Remember, Body

Body, remember not just how much you were loved,

not just the beds where you have lain,

but also those longings that so openly

glistened for you in the eyes,

and trembled in the voice—and some

chance obstacle arose and thwarted them.

Now that it’s all finally in the past

it almost seems as if you gave yourself to

those longings, too—remember how

they glistened, in the eyes that looked at you;

how they trembled in the voice, for you; remember, body.

[1916; 1917/1918]

Days of 1903

I never found them, ever again—all so quickly lost …

the poetic eyes, the pallid

face. … in the gloaming of the street. …

I’ve not found them since—things I came to have completely by chance,

things that I let go so easily;

and afterwards, in anguish, wanted back.

The poetic eyes, the pale face,

those lips, I haven’t found them since.

[1909; 1917]

The Afternoon Sun

This room, how well I know it.

Now it’s being rented out, with the one next door,

for commercial offices. The entire house has now become

offices for middlemen, and businessmen, and Companies.

Ah, this room, how familiar it is.

Near the door, here, was the sofa,

and in front of it a Turkish rug;

Close by, the shelf with two yellow vases.

On the right—no, opposite, a dresser with a mirror.

In the middle, the table where he’d write;

and the three big wicker chairs.

Near the window was the bed

where we made love so many times.

They must be somewhere still, poor things.

Near the window was the bed:

the afternoon sun came halfway up.

… At four o’clock in the afternoon, we’d parted

for one week only … Alas,

that week became an eternity.

[1918; 1919]

To Stay

One in the morning it must have been,

or half past one.

In a corner of that dive;

in back of the wooden partition.

Apart from the two of us, the place completely empty.

A kerosene lamp barely shed some light.

The vigilant servant was sleeping by the door.

No one would have seen us. But

we were so on fire for each other

that caution was beyond us anyway.

Our clothes were half undone—we weren’t wearing much,

since it was blazing hot, a heavenly July.

Delight in flesh amidst

clothes half undone:

quick baring of flesh—the image of it

has crossed twenty-six years; and now has come

to stay here in this poetry.

[1918; 1919]

Of the Jews (50 A.D.)

Painter and poet, runner and thrower,

Endymion’s beauty: Ianthes, son of Antonius.

From a family close to the Synagogue.

“The days that I most value are the ones

when I abandon the aesthetic quest,

when I forsake the beauty and rigor of the Hellenic,

with its overriding preoccupation

with perfectly formed and perishable white limbs.

And I become what I would like

always to remain: of the Jews, of the holy Jews, the son.”

A bit too heated, this declaration of his. “Always

remain of the Jews, of the holy Jews—”

But he didn’t remain one at all.

the Hedonism and Art of Alexandria

made the boy into their devotee.

[1912; <1919?]

Imenus

“… it should be loved all the more,

the pleasure that’s attained unwholesomely and in corruption;

only rarely finding the body that feels things as it wants to—

the pleasure that, unwholesomely and in corruption, produces

a sensual intensity, which good health does not know …”

A fragment of a missive

from the youth Imenus (of patrician stock), infamous

in Syracuse for dissipation,

in the dissipated times of Michael the Third.

[1915; 1919; 1919]

Aboard the Ship

It certainly resembles him, this small

pencil likeness of him.

Quickly done, on the deck of the ship:

an enchanting afternoon.

The Ionian Sea all around us.

It resembles him. Still, I remember him as handsomer.

To the point of illness: that’s how sensitive he was,

and it illumined his expression.

Handsomer, he seems to me,

now that my soul recalls him, out of Time.

Out of Time. All these things, they’re very old—

the sketch, and the ship, and the afternoon.

[1919; 1919]

Of Demetrius Soter (162–150 B.C.)

His every expectation turned out wrong!

He used to imagine that he’d do celebrated deeds,

would end the shame that since the time of the Battle

of Magnesia had ground his homeland down.

That Syria again would be a mighty power,

with her armies, with her fleets,

with her great encampments, with her wealth.

He endured it, grew embittered in Rome

when he sensed, in the conversation of his friends,

the scions of the great houses,

in the midst of all the delicacy and politesse

that they showed toward him, toward the son

of King Seleucus Philopator—

when he sensed that nonetheless there was always a hidden

disdain for the dynasties of the Greek East:

which were in decline, not up to serious affairs,

quite unfit for the leadership of peoples.

He’d withdraw, alone, and grow indignant, and swear

that it wouldn’t be the way they thought, at all.

Look, he has the will:

would struggle, would do it, would rise up.

If only he could find a way to reach the East,

manage to get away from Italy—

and all of this power that he has

in his soul, all this vehemence,

he’d spread it to the people.

Ah, if only he could be in Syria!

He was so little when he left his homeland

that he only dimly remembers what it looks like.

But in his thoughts he’s always studied it

like something sacred you approach on bended knee,

like an apparition of a beautiful place, like a vision

of cities and of harbors that are Greek.—

And now?

Now, hopelessness and dejection.

They were right, those lads in Rome.

It’s not possible for them to survive, the dynasties

that the Macedonian Conquest had produced.

No matter: he himself had spared no effort;

as much as he was able, he’d struggled on.

Even in his black discouragement,

there’s one thing that still he contemplates

with lofty pride: that even in defeat

he shows the same indomitable valor to the world.

The rest—was dreams and vain futility.

This Syria—it barely even resembles his homeland;

it is the land of Heracleides and of Balas.

[1915; 1919]

If Indeed He Died

“Where has he gone off to, where did the Sage disappear?

Following his many miracles,

and the great renown of his instruction

which was diffused among so many peoples,

he suddenly went missing and no one has learned

with any certainty what has happened

(nor has anyone ever seen his tomb).

Some have put it about that he died in Ephesus.

But Damis didn’t write that. Damis never

wrote about the death of Apollonius.

Others said that he went missing on Lindos.

Or perhaps that other story is

true, that his assumption took place on Crete,

in the ancient shrine of Dictynna.—

But nonetheless we have the miraculous,

the supernatural apparition of him

to a young student in Tyana.—

Perhaps the time hasn’t come for him to return,

for him to appear before the world again;

or metamorphosed, perhaps, he goes among us

unrecognized.—But he’ll appear again

as he was, teaching the Right Way. And surely then

he’ll reinstate the worship of our gods,

and our exquisite Hellenic ceremonies.”

So he daydreamed in his threadbare lodging—

after a reading of Philostratus’s

“Life of Apollonius of Tyana”—

one of the few pagans, the very few

who had stayed. Otherwise—an insignificant

and timid man—he, too, outwardly

played the Christian and would go to church.

It was the period during which there reigned,

with the greatest piety, the old man Justin,

and Alexandria, a god-fearing city,

showed its abhorrence of those poor idolators.

[1897; 1910; 1920; 1920]

Young Men of Sidon (400 A.D.)

The actor whom they’d brought to entertain them

declaimed, as well, a few choice epigrams.

The salon opened onto the garden;

and had a delicate fragrance of blooms

that was mingled together with the perfumes

of the five sweetly scented Sidonian youths.

Meleager, and Crinagoras, and Rhianus were read.

But when the actor had declaimed

“Here lies Euphorion’s son, Aeschylus, an Athenian—”

(stressing, perhaps, more than was necessary

the “valour far-renowned,” the “Marathonian lea”),

at once a spirited boy sprang up,

mad for literature, and cried out:

“Oh, I don’t like that quatrain, not at all.

Expressions like that somehow seem like cowardice.

Give—so I proclaim—all your strength to your work,

all your care, and remember your work once more

in times of trial, or when your hour finally comes.

That’s what I expect from you, and what I demand.

And don’t dismiss completely from your mind

the brilliant Discourse of Tragedy—

that Agamemnon, that marvelous Prometheus,

those representations of Orestes and Cassandra,

that Seven Against Thebes—and leave, as your memorial,

only that you, among the ranks of soldiers, the masses—

that you too battled Datis and Artaphernes.”

[1920; 1920]

That They Come—

One candle is enough. Its faint light

is more fitting, will be more winsome

when come Love’s— when its Shadows come.

One candle is enough. Tonight the room

can’t have too much light. In reverie complete,

and in suggestion’s power, and with that little light—

in that reverie: thus will I dream a vision

that there come Love’s— that its Shadows come.

[?; 1920]

Darius

The poet Phernazes is working on

the crucial portion of his epic poem:

the part about how the kingdom of the Persians

was seized by Darius, son of Hystaspes. (Our

glorious king is descended from him:

Mithridates, Dionysus and Eupator.) But here

one needs philosophy; one must explicate

the feelings that Darius must have had:

arrogance and intoxication, perhaps; but no—more

like an awareness of the vanity of grandeur.

Profoundly, the poet ponders the matter.

But he’s interrupted by his servant, who comes

running and delivers the momentous intelligence:

The war with the Romans has begun.

Most of our army has crossed the border.

The poet stays, dumbfounded. What a disaster!

How, now, can our glorious king,

Mithradates, Dionysus and Eupator,

be bothered to pay attention to Greek poems?

In the middle of a war—imagine, Greek poems.

Phernazes frets. What bad luck is his!

Just when he was sure, with his “Darius,”

to make his name, and to reduce his critics,

those envious men, to silence at long last.

What a setback, what a setback for his plans!

And if it had only been a setback: fine.

But let’s see if we are really all that safe

in Amisus. It’s not a spectacularly well-fortified land.

The Romans are most fearsome enemies.

Is there any way we can get the best of them,

we Cappadocians? Could it ever happen?

Can we measure up to the legions now?

Great gods, protectors of Asia, help us.—

And yet in the midst of all his upset, and the disaster,

a poetic notion stubbornly comes and goes—

far more convincing, surely, are arrogance and intoxication;

arrogance and intoxication are what Darius would have felt.

[<1897?; 1917; 1920]

Anna Comnena

She laments in the prologue to her Alexiad,

Anna Comnena laments her widowhood.

Her soul is in muzzy whirl. “And with

freshets of tears,” she tells us, “I deluge

mine eyes. … Alack the breakers” of her life,

“alack for the upheavals.” Anguish burns her

“unto the very bones and marrow and rending of my soul.”

Nonetheless the truth seems to be that she knew one

mortal grief alone, that power-loving woman:

that she had only one profound regret

(even if she won’t acknowledge it), that supercilious Greekling:

for all of her dexterity she didn’t manage

to secure the Throne; instead he took it

practically right out of her hands, that upstart John.

[1917; 1920]

Byzantine Noble, in Exile, Versifying

Let the dilettantes call me dilettante.

In serious matters I have always been

most diligent. And on this I will insist:

that no one has a better knowledge of

Church Fathers or Scripture, or the Synodical Canons.

On every question that he had, Botaniates—

every difficult ecclesiastical matter—

would take counsel with me, me first of all.

But since I’ve been exiled here (curse that spiteful

Irene Ducas) and am frightfully bored,

it’s not at all unseemly if I divert myself

by crafting verses of six or seven lines—

divert myself with mythological tales

of Hermes, and Apollo, and Dionysus,

or the heroes of Thessaly and the Peloponnese;

or with composing strict iambic lines

such as—if I do say so—the litterateurs

of Constantinople don’t know how to write.

That strictness, most likely, is the reason for their censure.

[1921; 1920]

Their Beginning

The fulfillment of their illicit pleasure

is accomplished. They’ve risen from the bed,

and dress themselves quickly without speaking.

They emerge separately, covertly, from the house. And while

they walk rather uneasily in the street, it seems

as if they suspect that something about them betrays

what kind of bed they’d fallen into just before.

Nonetheless, how the artist’s life has gained.

Tomorrow, the day after, or through the years he’ll write

powerful lines, that here was their beginning.

[1915; 1921]

Favour of Alexander Balas

Oh I’m not put out because my chariot’s

wheel was smashed, and I’m down one silly win.

I shall pass the night among fine wines

and lovely roses. All Antioch is mine.

I am the most exalted of young men.

I’m Balas’s weakness, the one he worships.

Tomorrow, you’ll see, they’ll say the race wasn’t proper.

(But if I were vulgar, and had secretly given the order—

they’d even have placed my crippled chariot first, the flatterers.)

[1916?; 1921]

Melancholy of Jason, Son of Cleander: Poet in Commagene: 595 A.D.

The aging of my body and my looks

is a wound from a terrible knife.

I have no means whatsoever to endure it.

Unto you I turn, Art of Poetry,

you who know something of drugs;

of attempts to numb pain, in Imagination and Word.

It’s a wound from a terrible knife.—

Bring on your drugs, Art of Poetry,

which make it impossible—for a while—to feel the wound.

[1918?; 1921]

Demaratus

The theme, “The Character of Demaratus,”

which Porphyry has suggested to him in conversation,

the young scholar outlined as follows

(intending, afterwards, to flesh it out rhetorically).

“At first the courtier of King Darius, and then

a courtier of King Xerxes;

and now accompanying Xerxes and his army,

to vindicate himself at last: Demaratus.

“A great injustice had been done to him.

He was the son of Ariston. Shamelessly

his enemies had bribed the oracle.

Nor did they fail to deprive him of his throne;

but when at last he yielded, and decided

to resign himself to living as a private person

they had to go and insult him before the people,

they had to go and humiliate him, in public, at the festival.

“And so it is that he serves Xerxes with such great zeal.

Accompanying the enormous Persian army

he too will make his return to Sparta;

and, a king once more, how swiftly

he will drive him out, will degrade

that conniving Leotychides.

“And so his days pass by, full of concerns:

giving the Persians counsel, explaining to them

what they need to do to conquer Greece.

“Many worries, much reflection, which is why

the days of Demaratus are so dreary.

Many worries, much reflection, which is why

Demaratus doesn’t have a moment’s pleasure;

since pleasure isn’t what he’s feeling

(it’s not; he won’t acknowledge it;

how can he call it pleasure? it’s the acme of his misfortune)

when everything reveals to him quite clearly

that the Greeks will emerge victorious.”

[1904; 1911; 1921]

I Brought to Art

I’m sitting and musing. I brought to Art

longings and feelings— some half-glimpsed

faces or lines; some uncertain mem’ries

of unfulfilled loves. Let me submit to it.

It knows how to shape the Form of Beauty;

almost imperceptibly filling out life,

piecing together impressions, piecing together the days.

[1921; 1921]

From the School of the Renowned Philosopher

He remained Ammonius Saccas’s student for two years;

but of philosophy and of Saccas he grew bored.

Afterward he went into politics.

But he gave it up. The Prefect was a fool;

and those around him solemn, pompous stiffs;

their Greek horribly uncouth, the wretches.

His curiosity was aroused,

a bit, by the Church: to be baptized,

to pass as a Christian. But he quickly

changed his mind. He’d surely get in a row

with his parents, so ostentatiously pagan:

and they’d immediately put an end—an awful thought—

to his extremely generous allowance.

Still, he had to do something. He became an habitué

of the depraved houses of Alexandria,

of every secret den of debauchery.

In this, fortune had been kind to him:

had given him a form of highest comeliness.

And he delighted in that heavenly gift.

For at least another ten years yet

his beauty would endure. After that—

perhaps to Saccas he would go once more.

And if in the meantime the old man had died,

he’d go to some other philosopher or sophist;

someone suitable can always be found.

Or in the end, it was possible he’d even return

to politics—admirably mindful

of his family traditions,

duty to one’s country, and other pomposities of that sort.

[1921; 1921]

Maker of Wine Bowls

On this mixing-bowl of the purest silver—

which was made for the home of Heracleides,

where great elegance always is the rule—

note the stylish blooms, and the brooks, the thyme;

and in the middle I put a beautiful young man,

naked, sensuous; he still keeps one leg,

just one, in the water.— O Memory, I have begged

to find in you the best of guides, that I might make

the face of the youth I loved as it really was.

This has proved to be very difficult since

some fifteen years have passed since the day on which

he fell, a soldier, in the defeat at Magnesia.

[1903; 1912; 1921]

Those Who Fought on Behalf of the Achaean League

You brave, who fought and fell in glory:

who had no fear of those who’d conquered everywhere.

You blameless, even if Diaeus and Critolaus blundered.

Whensoever the Greeks should want to boast,

“Such are the men our race produces,” is what they’ll say

about you. That’s how marvelous the praise for you will be.—

Written in Alexandria by an Achaean:

in the seventh year of Ptolemy, the “Chickpea.”

[1922; 1922]

For Antiochus Epiphanes