Полная версия:

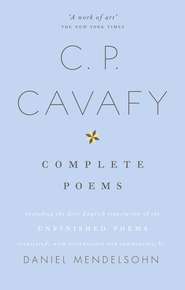

The Complete Poems of C.P. Cavafy

Given the importance of this technique in Cavafy’s prosody, the meticulous care with which he constructed each line, I’ve tried to structure the English of these translations so that it achieves the same effect.

One final note, concerning a choice on my part that might strike some readers as controversial. In rendering Greek names from the Classical, Hellenistic, Late Antique, and Byzantine past, I have consistently chosen to eschew a phonetic rendering of the way those names sound in Greek, opting instead to adopt the traditional, Latinate forms—which is to say, the forms that will be familiar to English speakers. To my mind, mimicking the contemporary Greek pronunciation of the names of the historical or pseudohistorical characters is, at best, inappropriate and indeed unhelpful in an English translation. When the Greek eye sees the name

Worse, a misguided allegiance to the sound of Modern Greek can lead to a serious misrepresentation of a poem’s deeper meanings. To take “The Seleucid’s Displeasure” once more: certain translators have chosen to render the title of this poem as “The Displeasure of Selefkidis”—that last word being an accurate phonetic reproduction of what the Greek word

4

THE PRESENT VOLUME collects all of the known poetic work of Cavafy. Because of the complexities of their publication history, the organization of the poems in the pages that follow merits brief comment.

Although he published a small number of verses, most of them when he was young, in literary journals and annuals, Cavafy had for most of his career a highly idiosyncratic method of presenting his poems, and never published a definitive collection of them in book form. He preferred, instead, to have poems printed at his own expense as broadsheets or in pamphlets, which he would distribute to a select group of friends and admirers. Among other things, this method allowed the poet to treat every poem as a work in progress; friends recalled that he often went on emending poems after they had been printed. In an essay called Independence, the poet articulated what was clearly a kind of anxiety about the finality associated with publication:

When the writer knows pretty well that only very few volumes of his edition will be bought … he obtains a great freedom in his creative work. The writer who has in view the certainty, or at least the probability of selling all his edition, and perhaps subsequent editions, is sometimes influenced by their future sale … almost without meaning to, almost without realizing—there will be moments when, knowing how the public thinks and what it likes and what it will buy, he will make some little sacrifices—he will phrase this bit differently, and leave out that. And there is nothing more destructive for Art (I tremble at the mere thought of it) than that this bit should be differently phrased or that bit omitted.

Still, after a time he would periodically order modest printings of booklets that contained small selections of the poems, arranged thematically. The first of these, Poems 1904, contained just fourteen poems; a second, Poems 1910, added seven more, and a later manuscript of that booklet (known, because the poet copied it out by hand as a gift to his friend and heir, as the “Sengopoulos Notebook”) added one more early poem—“Walls”—which had been written in 1897 and much anthologized, bringing the total to twenty-two. These and subsequent booklets (and sometimes the poems in them) were constantly being revised, added to, and subtracted from: hence Poems 1910 became Poems (1909–1911), and then Poems (1908–1914), and so on, according to which works the poet had decided to add or remove.

By the time Cavafy died, there were three such collections in circulation. Two were bound, and arranged thematically: Poems 1905–1915, containing forty poems (the dates refer to the year of first publication), and Poems 1916–1918, containing twenty-eight poems. The third, Poems 1919–1932, a collection of sixty-nine poems arranged chronologically by date of first publication, was merely a pinned-together sheaf of individual sheets. These 137 poems, together with one poem that Cavafy had corrected for the printer in the weeks before his death, “On the Outskirts of Antioch,” and sixteen early poems from the Sengopoulos Notebook, all first published between 1897 and 1904, that had not already been collected in Poems 1905–1915, are the 154 poems that appeared in the first commercial collection of his work, lavishly published (in a chic Art Deco style) in Alexandria two years after Cavafy’s death, edited by Rika Sengopoulou, the first wife of his heir.

Although this group of poems is now often referred to as “the Canon”—a word, one suspects, that would have caused Cavafy to raise an eyebrow, given his sardonic appreciation for the difference between the judgments we pass and those that history passes—I refer to them here as the Published Poems, since these are the works that this most fastidious of poets published, or approved for publication, during his own lifetime, precisely as he wanted them to be read. They appear here in the following order: (1) Poems 1905–1915; (2) Poems 1916–1918; (3) Poems 1919–1933 (including “On the Outskirts of Antioch”); a fourth section, which I have entitled “Poems Published 1897–1908,” offers the contents of the Sengopoulos Notebook, minus of course the six poems that already appear in Poems 1905–1915. (It is worth remembering that Cavafy was eager to take Poems 1910, the basis for the Sengopoulos Notebook, out of circulation in the years after its publication.) It is true that this presentation of the latter group wrests them from the poet’s careful thematic arrangement, in which each poem is meant to comment on and, as it were, converse with its neighbor; but it would be awkward, to say nothing of pedantic, to repeat six poems in two successive sections. For the sake of readers who want to experience the Sengopoulos Notebook as Cavafy arranged it, I have included, before this final section of the Published Poems, a list of the poems giving the order in which they appeared in the Notebook.

Because they were works about which the poet had mixed feelings, I have decided to place the remaining poems, some of which are very early, after those that the poet approved for publication. These appear in roughly chronological order. First come the twenty-seven Repudiated Poems, originally published between 1886 and 1898 and subsequently renounced by the poet. These are followed by the Unpublished Poems. The latter is a group of seventy-seven texts (including three written in English) that Cavafy completed but never approved for publication, and which he kept among his papers, many of them bearing the notation “Not for publication, but may remain here.” The first of these was written when the poet was around fourteen; the last was written in 1923, when he was sixty. Thirteen found their way into print after World War II, and a complete scholarly edition of the entire group, edited by George Savidis, was published in Athens, in 1968. A subsequent edition, published by Mr. Savidis in 1993, gives to them a new name, “Hidden Poems,” but I have retained the old designation, “Unpublished,” both in my text and in my notes, since I believe that “unpublished” adequately suggests the poet’s attitude toward those works without introducing speculative psychological overtones. In the present volume I have included translations of all seventy-four of the Unpublished Poems that were written in Greek, as well as the texts of the three poems Cavafy wrote in English, since they are original works; I have omitted from the present translation the poet’s five translations into Greek of works in other languages, of which three are from English. Readers will also find translations of the three remarkable Prose Poems among the Unpublished Poems.

The fourth and final section of this volume contains the Unfinished Poems, drafts that Cavafy had begun between 1918 and 1932 (see the discussion below).

A final word, about the appearance of the poems on the page. As we know, the dates of composition and subsequent publication of Cavafy’s poems is often suggestive: it surely meant something that he spent fifteen years returning to and polishing “The City” before he chose to publish it. According to Sarayannis,

Cavafy himself told me that he never managed to write a poem from beginning to end. He worked on them all for years, or often let them lie for whole years and later took them up again. His dates therefore only represent the year when he judged that one of his poems more or less satisfied him.

Given the importance of those dates, I have chosen to note them at the bottom of the page(s) on which the poems appear in the main portion of this text, rather than cluttering the notes at the back with one-line items (“Written in 1917, published in 1918”). To do so, I have adopted the following system of notation. When known, the year of original composition (and of subsequent rewriting, if there was one and if we know when it occurred) appears in italics; the year (or years) of publication appear in roman type. Hence, for example, in the case of the Published Poem “Song of Ionia,” of which an early version was written at some point before 1891 and then published in 1896, only to be subsequently revised in 1905 and published in its final form in 1911, the notation reads as follows: [1891; 1896; 1905; 1911].

In the case of the Unpublished Poems—the date of whose first publication, long after the poet’s death, does not, by contrast, shed any light on his feelings or intentions—I have merely added the year of composition, in parentheses, after the title of each poem. In the case of the Unfinished Poems, the year that appears in parentheses refers to what George Savidis, who discovered the drafts, called “the date of first conception,” which Cavafy noted on the dossier for each draft. In both cases, the addition of the date to the title has, I think, the virtue of making those poems visually distinct from the ones that Cavafy himself chose to publish—however he may have subsequently felt about them. Readers today are, indeed, likely to find more to admire, or at the very least to learn from, in the poems that Cavafy suppressed than the poet himself would have suspected.

5

IN THE AUTUMN OF 1932, at the end of a four-month sojourn in Athens that also marked the beginning of the end of his life, Cavafy revealed with some agitation that he had important unfinished business to attend to. “I still have twenty-five poems to write,” he declared to some friends, in the distorted whisper to which his famously mellifluous and enchanting voice had been reduced following the tracheotomy that was meant to save him from throat cancer, and which was the reason he’d come to Athens from Alexandria. “Twenty-five poems!”

The conversation, recalled by one of the friends to whom he’d spoken that day and reported after Cavafy’s death in April of the following year, was merely the first of what turned out to be several tantalizing references to a body of unfinished work that the poet was desperately trying to complete as death closed in. Ten years later, in 1943, someone who’d been engaged in compiling Cavafy’s bibliography during the very year in which the poet had traveled to Athens seeking medical help revealed that Cavafy had made it plain to him that the bibliography was far from complete. In 1963, on the thirtieth anniversary of Cavafy’s death, someone else wrote in to a newspaper claiming that, during those last months, the dying poet had written him to say that he still had fifteen poems to finish.

The mysterious texts to which these various hints alluded were finally identified, also in 1963, by the scholar George Savidis, Cavafy’s great editor, after an inspection of the Cavafy Archive, which Savidis himself eventually came to possess after acquiring it from Cavafy’s friend and heir, Alexander Sengopoulos. A year later, in an article about material in the Archive that had yet to be published (some of which—those poems that Cavafy had completed but did not approve for publication—he would publish in 1968 as “The Unpublished Poems”), Savidis revealed, with the deep emotion of an archaeologist making a great discovery, the existence of a cache of incomplete drafts, composed between 1918 and 1932, that the poet had left, meticulously labeled and organized, among his papers:

More interesting still are the sketches of 25 poems that Cavafy was unable to finish, and on which he was working, with great difficulty, during the last months of his life. Carefully wrapped by him in makeshift envelopes, each with its provisional title and the date, I imagine, of its first conception, they proceed from 1918 to 1932, and along with the very full drafts of some of the published work (like “Caesarion”) and some of the unpublished but completed poems, they give us a unique, unhoped-for, and tremendously moving look at the stages of Cavafian creation.

Closer inspection eventually revealed that there were, in fact, thirty drafts in all, along with a handful of fragmentary texts. In time, Savidis entrusted the task of editing these drafts, some of them awaiting the most minor of finishing touches, others apparently in the final stages of preparation but complicated by various textual problems, to the Italian scholar Renata Lavagnini. A professor of Modern Greek at the University of Palermo and member of the Istituto Siciliano di Studi Bizantini e Neoellenici (the Sicilian Institute of Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies, founded by her father, the great Byzantinist and Neohellenist Bruno Lavagnini), she is both an authority on the literary aspects of Cavafy’s work and a meticulous philologist. As a specialist in textual criticism, Professor Lavagnini was particularly well equipped to tackle the technical problems associated with editing a mass of manuscript drafts into coherent texts—although, as she herself would be the first to emphasize, these texts must always remain, at best, hypothetical; something the reader must bear in mind.

The heroic task of sifting through these sometimes illegible sketches, of teasing out, from crossed-out lines and scribbled-in insertions, each discrete stage (or, as the poet called it, morfí, “form”) in the evolution of a given poem, of arriving at the likely last form taken by each work, and of meticulously annotating textual issues, as well as providing a thoroughgoing literary and historical commentary, took decades, but there can be no doubt that the result was worth the wait. The fruits of Professor Lavagnini’s labor, published as a scholarly Greek edition in 1994, gives this important body of poetic work to the world in a lucidly presented form; it bears the title chosen by Savidis, by which it will hereafter be known: Ateli piimata, the “Unfinished Poems.” (The adjective ateli in Greek suggests, too, a state of “imperfection.”) Thanks to the generous cooperation of the Cavafy Archive, I have the privilege of making this vitally important addition to our understanding of one of the twentieth century’s greatest poets available to English speakers for the first time.

The Unfinished Poems are unusual in at least one crucial respect. More often than not, when previously unknown manuscripts by major authors unexpectedly come to light, the material in question is juvenilia: immature work from the earliest phase of the artist’s career, which he or she has discarded or repressed and which, either through the dogged detective work of dedicated scholars or through happy accidents, suddenly sees the light of day once more. The discovery, in 1994, of Louisa May Alcott’s first novel, which languished in the Harvard University Library until it was discovered by a pair of professors researching Alcott’s papers, and the 2004 discovery of the complete draft of an early novel of Truman Capote among some papers and photographs that had passed into the hands of a former house sitter, are but two recent examples. And yet as exciting and dramatic as these revelations can be, such work tends, inevitably, to be interesting less for any inherent artistic value it possesses than for the light it can shed on the writer’s creative development.

The thirty Unfinished Poems of Cavafy, by contrast, represent the last and greatest phase of the poet’s career: the decade and a half from 1918, when Cavafy was fifty-five—and when, too, he published the first of his “sensual” (or “aesthetic”) poems that were explicitly homosexual in nature—until the year before his death at the age of seventy. For this reason they are of the deepest significance not merely inasmuch as they illuminate the existing works—the Published, Unpublished, and Repudiated Poems—but as serious works of art in themselves, the deeply wrought products of a great poetic consciousness at its peak.

The publication of a writer’s unfinished work is, inevitably, an enterprise that raises complicated questions. This is particularly true in the case of a writer like Cavafy, who ruthlessly culled his own work every year, suppressing anything that did not meet his exacting standards—a process that suggests a stringent adherence to the very highest criteria of polish and perfection. But there is persuasive evidence that Cavafy considered the thirty drafts presented here as work he eventually meant to be recognized and published. The Cavafy Archive contains two lists that the poet made of work in progress: one dates to 1930, and the other was kept and constantly revised between 1923 and 1932. The former contains the titles of twenty-nine poems, of which twenty-five are all of the Unfinished drafts he’d composed by that time, and the latter records the titles of fifty poems, a figure that includes all thirty of the Unfinished drafts. All of the other poems listed in these indices are works Cavafy eventually sent to the printer. Hence the lists strongly indicate that the poet—who, as we know from the manuscripts of his Unpublished Poems, was perfectly willing to mark a finished poem with a note declaring that it “need not be published. But it may continue remaining here. It does not deserve to be suppressed”—made no distinction between those poems that he published and the ones he did not, in the end, have time to complete and publish. It was only time, and finally death, that consigned them, for a while, to obscurity.

“Light on one poem, partial light on another.” Cavafy’s 1927 remark is perhaps nowhere more apt than in the case of the Unfinished Poems. Readers encountering these works will immediately see how fully they partake of Cavafy’s special vision as I have described it above, and part of the excitement of reading them for the first time comes, indeed, from the way they seem to fit into the existing corpus, taking their place beside poems that are, by now, well known; there is a deep pleasure in having, unexpectedly, more of what one already loves. But a great deal of the excitement generated by the Unfinished Poems derives, even more, from the new “light,” as the poet put it, that they now shed on existing work—on our knowledge of the poet, his techniques, methods, and large ambitions.

Of these thirty texts, nine treat contemporary subjects that will be familiar to readers already at home in the poet’s world. There are evocative treatments of the memory of a deliciously illicit encounter on a wharf (“On the Jetty”), and an elderly poet’s reverie about long-past days in which he was a member of a gang of rough young men living at the fringes of society—and on the wrong side of the law (“Crime”). One has as its subject a photograph that elicits thoughts of a bygone love (“The Photograph”); it is a crucial addition to a small but vivid group of poems already known (“That’s How,” “From the Drawer,” “The Bandaged Shoulder”) that indicate how intrigued the poet was by photography and how suggestively it could figure in his work. A short but vivid lyric, entitled simply “Birth of a Poem,” casts a gentle, lunar light on our understanding of the way in which the poet imagined his own creative process to have worked (“imagination, taking / something from life, some very scanty thing / fashions a vision. …”).

A striking longer work, “Remorse,” takes its place beside the most emphatic of Cavafy’s philosophical poems—“Hidden Things,” “Che Fece … Il Gran Rifiuto”—while expanding their moral vision, adding a new note of gentle forgiveness for the unwitting cruelties to which fear and repression condemn us. Surely two of the most remarkable of these contemporary poems are “The Item in the Paper,” where the melodramatic donnée—a young man is reading an item in a paper about the murder of a youth with whom he’d had a liaison—becomes the vehicle for a tender and devastating exploration of a favorite theme, the soul-destroying effects of taboos against illicit love, and the hypocrisy of those who impose them; and “It Must Have Been the Spirits,” the lyric (discussed above, p. XXXVII), about the nocturnal apparition of Cavafy’s younger self, a work in which, as in some of Cavafy’s greatest poems with this motif—“Since Nine—,” “Caesarion”—past and present, the quotidian and the intensely erotic, become disorientingly, thrillingly blurred.

The remaining twenty-one lyrics are historical in nature, although here, as with the best of Cavafy’s work, this label is often a matter of convenience. They have familiar Cavafian settings. There are Hellenistic powers teetering—often unbeknownst to the poems’ smug narrators—on the brink of implosion (“Antiochus the Cyzicene,” “Tigranocerta,” “Agelaus,” “Nothing About the Lacedaemonians”); the corrupted Egypt of the incestuous Ptolemies (“The Dynasty,” “Ptolemy the Benefactor [or Malefactor]”); the Greek-speaking margins of the Roman Empire (the setting of “Among the Groves of the Promenades,” the fourth and last of Cavafy’s Apollonius of Tyana poems, this one about the sage’s sudden, telepathic apprehension, in Ephesus, of Domitian’s murder back in Rome). The early Christian era is vividly represented (“Athanasius,” about the Christian bishop who was ill treated by Julian the Apostate, a recurring Cavafian character), as are the peripheries of the Greek-speaking world during the twilight of Late Antiquity (“Of the Sixth or Seventh Century”). And of course there is the vast arc of Byzantium, from Justinian (the subject of the spooky short lyric “From the Unpublished History”) to the empire’s final days.

To the latter epoch, poignant to any Greek, belongs what is surely one of the most striking of any of Cavafy’s poems, finished or unfinished: “After the Swim.” Here the poet, as often in his greatest mature creations, dissolves the distinctions between “historical” and “erotic” poetry, seducing the reader into thinking that the setting is, in fact, that of the late masterpiece “Days of 1908”—a hot Mediterranean day, a seaside swim, naked ephebic bodies—only to reveal, somewhat disorientingly, that we are in the waning days of Byzantium, haunted by the memory of the great scholar Gemistus Plethon, whose own identity (loyally Christian? covertly pagan?) was itself rather vexed.