Полная версия:

Garden Birds

The presence of non-native berry-producing shrubs in gardens, while potentially a valuable food resource for visiting birds, brings with it a possible conservation issue. Since birds are the main dispersal agent for the seeds held within berries, they are a potential route by which non-native species may become more widely established within the wider countryside (Greenberg & Walter, 2010).

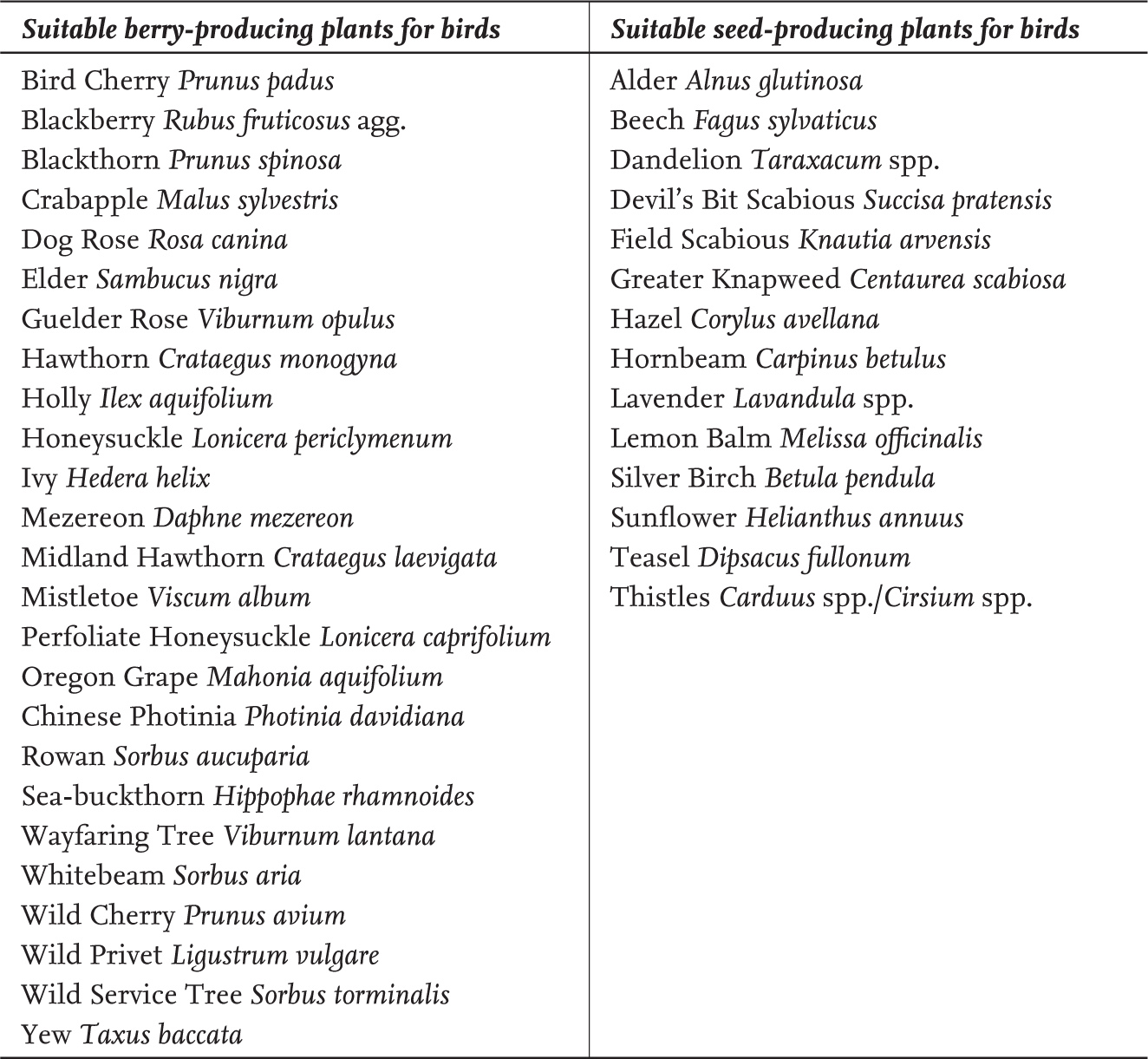

It is not just the berries that birds seek; some, such as Greenfinch, are after the seeds themselves. This can prompt plants to incorporate toxic compounds into the seed coat or its lining. Although it is the absence within the wider countryside of the seeds of larger shrubs and trees that can drive birds to garden feeding stations (see later in this chapter), it is important to note that some of our garden birds specialise in the seeds of smaller plants. The Goldfinch, for example, specialises in seeds of the Compositae family, particularly the thistles and dandelions and it is this habit that probably first brought them into gardens to feed on ornamental thistles, teasel, lavender and cornflower (Glue, 1996). Maddock (1988) reports how, from the winter of 1983/84, a few Goldfinches would visit a suburban Oxfordshire garden to feed on lavender and dry teasel heads. Their interest was maintained by brushing the teasel heads with Niger. Over the following winter, up to two dozen Goldfinches again visited the teasel head before turning to a mix of Niger, canary seed and millet provided at a garden feeding station. Important berry- and seed-producing plants for birds are shown in Table 4.

TABLE 4. Suitable plants for providing berries and seeds for garden birds. Adapted from Toms et al., (2008).

On occasion, garden birds have been reported stealing nectar from flowering plants, the latter typically exotic species whose flowers show features used to attract birds as pollinators (Búrquez, 1989; Proctor et al., 1996). Reports from within the UK have included Blue Tit – feeding from Crown Imperial Fritillaria imperialis (Thompson et al., 1996); Blackcap – feeding from Mahonia (Harrup, 1998); and Blackcap feeding from Kniphofia. In addition, the behaviour is widely recognised in a number of the warbler species migrating through the Mediterranean region (Cecere et al., 2011). Nectar feeding has also been recorded for a number of European plants (see the review by Ford, 1985), including those in the genera Rhamnus, Ferula, Acer, Crataegus, Ribes and Salix.

Nectar feeding is thought to be a widespread behaviour in UK Blue Tits, with the species recorded feeding from a variety of flowers across 33 counties within the UK (Fitzpatrick, 1994). There has also been a small amount of more detailed work, examining the contribution that nectar taken from Flowering Currant Ribes sanguineum makes to Blue Tit spring diet (Fitzpatrick, 1994). This revealed that although the nectar was not the preferred food – it was used most when peanuts were unavailable because of competition from other birds – it was a highly profitable food source, contributing up to 50 per cent of the average daily metabolic rates of the Blue Tits studied. The use of nectar sources by suburban populations of predominantly nectar-feeding birds has been examined in Australia, with a view to understanding the contribution that native and exotic shrubs make towards the available nectar resource (French et al., 2005).

FOOD SELECTION BY GARDEN BIRDS

The contribution that food provisioned at garden feeding stations makes to the energetic and nutritional requirements of garden birds varies between seasons and between species. It also varies between the different types of food provided, with some higher in fat or protein content than others, and with differences in the amount of time required to ‘handle’ and process the food. It is difficult to study the feeding preferences of birds out in the field, particularly in a garden setting where individual birds can find alternative feeding opportunities nearby. A small amount of work has been done here in the UK with, for example, Greenwood & Clarke (1991) examining the selection of black-striped sunflower seeds and peanuts – peanuts were the preferred food taken.

One of the biggest studies to have been carried out was that undertaken by Geis (1980) in the United States. The study, carried out between November 1977 and July 1979, made use of a network of volunteers, observing and recording feeding preferences at specially designed feeding stations, capturing details of 179,000 feeding visits. Geis adopted a standard approach, whereby the food types being tested were compared against two ‘standard’ foods commonly provided by householders: black-striped sunflower seed and white proso millet. The results of the work underlined a general pattern of preferences across the bird species visiting and also highlighted the individual preferences of particular species. American Goldfinch, for example, favoured hulled sunflower seeds over Niger, with Niger favoured over oil-type sunflower seeds, black-striped sunflower seeds and white proso millet. In contrast, House Sparrows favoured white proso millet but would feed on almost anything, with the exception of flax and rape seed. Selection of Niger by fine-billed finches is something that has been documented in other studies (Horn et al., 2014).

FIG 26. Large-billed species like House Sparrow are more likely to take larger seeds from a seed mix, the smallest seeds being difficult for them to handle. (John Harding)

The abilities of wild birds to select foodstuffs based on their nutritional characteristics is, as we have just seen in relation to fruits and berries, evident from observational studies; it is also evident from experimental work, though this is more limited. Work on Common Myna Acridotheres tristis has, for example, revealed that urban populations display a strong preference for food with a high protein content, favouring this over foods with high lipid and high carbohydrate contents in field-based trials (Machovsky-Capuska et al., 2016). This work suggested that these urban Common Mynas were protein limited, something reinforced by the way in which the birds competed for access to this food.

Two reportedly individually identifiable Blue Tits, visiting a bird feeder in a suburban Belfast garden during winter, were estimated to have obtained 25.36 per cent and 44.47 per cent of their daily energy requirements from peanuts (Fitzpatrick, 1995); comparable figures from the same study for two Great Tits were 16.41 per cent and 22.2 per cent. Although this study doesn’t adequately deal with questions over how the birds could be recognised as individuals from their plumage characteristics, the work has been used to suggest that these suburban individuals were obtaining a significant component of their daily energy requirement from the food supplied. Better-documented studies, this time on provisioned Black-capped Chickadees Poecile atricapillus in Alaska, found that individuals were obtaining up to 29 per cent of their daily energy requirements from the food supplied (Brittingham & Temple, 1992a; Karasov et al., 1992).

Selection for particular food items might also be shaped by how that food is presented. Garden bird species that would feed within trees and shrubs when foraging in the wider countryside – such as the tits – were some of the first to take advantage of seeds and peanuts presented in hanging feeders and mesh cages. The strong feet of these species enable them to grip hold of small perches or mesh, something that ground-feeding species like Robin, Dunnock and Blackbird would find too challenging. These latter species would be more likely to feed from a bird table or to take food from the ground. Changes in feeder design, most notably in the shape and size of feeder perches, can exert a big influence on which birds are then able to feed. The move from a straight perch to an ‘o’ shaped perch seems to have aided Robins to feed from hanging feeders. The advice to those feeding garden birds is to feed a range of foods in a number of different ways, providing opportunities for the different species and their favoured means and locations for taking food.

FIG 27. Like Robin and Wren, the Dunnock prefers to feed on the ground but it will venture onto bird tables and, occasionally, onto hanging feeders. (John Harding)

HOW AND WHEN BIRDS USE GARDEN FEEDERS

As we will see in the following section, the use of garden feeding stations is influenced by food availability over wider areas, from that available in the nearby countryside to that available many hundreds of miles away in other countries. Before we turn to look at the use of gardens in this wider context, we will start by looking at how the location of feeding opportunities within a garden can influence its use. The foraging behaviour of small birds is influenced by the conflicting demands of needing to feed but also to avoid predators; during the breeding season, the need to maintain a territory and attract a mate can, for many individuals, also be added to these demands (Lima & Dill, 1990). These considerations are likely to influence key decisions about where and when to feed, and we know, for example, that the pattern of arrivals and departures throughout the day at garden feeding stations is shaped by the balance of risk between starvation and predation.

Juvenile Blue Tits and Great Tits are known to be subordinate to older individuals and have been shown to make greater use of bird feeders located further from cover (and with a higher risk of Sparrowhawk Accipiter nisus predation) than adult birds. Hinsley et al. (1995) reported that 40 per cent of the tits they trapped at a feeder located close to cover were adults, with this figure dropping to 17 per cent at a feeder located further away. Another garden-based study found a similar pattern, this time looking at a number of garden bird species (Cowie & Simons, 1991). Cowie and Simons found that total food consumption declined with distance from cover in their experimental study using feeders positioned at different distances from vegetation. The House Sparrows in their study only used the feeder closest to cover, with Blue Tit only slightly more willing to feed further out into the garden. Only Greenfinch seemed comfortable feeding on the more exposed feeders; this species tended to arrive to feed in sizeable flocks and it seems likely that this flocking behaviour increased the chances that a potential predator would be spotted early enough for the birds to make their escape. Interestingly, the proportion of time that individual birds spent manipulating food items decreased in favour of increased vigilance when birds were feeding further from cover, again underlining the need to balance the energetic and nutritional returns against the risk of predation. Krebs (1980), looking at handling times in Great Tits, found that food-deprived individuals demonstrated shorter food-handling times than satiated individuals, presumably because they spent less time scanning for predators in order to take on board as much food as possible. A study by Suhonen (1993) has also demonstrated that foraging site selection in tits – this time mixed flocks of Crested Tit Lophophanes cristatus and Willow Tit Poecile montana – is influenced by a combination of the dominance relationships present and the perceived risk of predation by Pygmy Owls Glaucidium passerinum.

Most small birds will rush to the available cover if a predator is detected nearby; at some point they must then make a decision to leave the safety that the cover provides in order to resume feeding. Several pieces of work demonstrate that this return to feeding is influenced by the age and status of the individuals involved. De Laet (1985), Hegner (1985) and Hogstad (1988) found that dominant Great Tits, Blue Tits and Willow Tits (respectively) typically would not leave the available cover until subordinate individuals had first done so. Some individuals will make use of the available cover more directly, for example by carrying food items from feeders into nearby cover for consumption. Research has demonstrated that the chances of a bird doing this increase as the distance to cover decreases, the size of the food item increases or if the individual is less dominant than other individuals that are also using the feeding stations. In the UK, Coal Tits will often remove food from feeding stations to consume elsewhere, presumably because they are some way down the pecking order.

FIG 28. The small size of the Coal Tit, and its low ranking within the garden bird dominance hierarchy, may be one reason why this species often takes a seed from a garden feeding station to eat it in a nearby bush or shrub. It may also cache seed for use at a later date. (John Harding)

The balance of energetic demands, predation risk and competition from other individuals also shapes the time at which birds feed over the course of a day. We are all familiar with the dawn peak in feeding activity seen in garden birds here in the UK. However, this is not the only peak in activity seen at garden feeding stations, since many observers have reported a second peak towards late morning and a third just before dusk. Fitzpatrick (1997) examined these temporal patterns in feeder use by studying the birds visiting feeders in a Belfast garden. Her work, carried out during the winter months, revealed the patterns of activity at garden feeders for House Sparrow, Blue Tit and Great Tit. Although there were some differences between the three species, the broad patterns underlined the three peaks reported elsewhere.

The use of garden feeders may also be influenced by which other species are present, perhaps mediated through dominance hierarchies (see Chapter 6), or because of individual behaviour. The use of camera traps and PIT tags (which allow the automated identification of individual birds) has enabled researchers to look at some of the factors that may modify the ways in which feeding stations are accessed. Galbraith et al. (2017b), for example, have been able to establish if individual birds are consistent in their use of supplementary food over time or whether use might vary seasonally. Working in New Zealand, the researchers found that although House Sparrows were numerous at monitored feeding stations, individuals were highly variable in their feeder use. In contrast, feeding station use by visiting Spotted Doves Streptopelia chinensis tended to be based around a core group of individuals who were highly consistent in their behaviour. Work carried out in the UK (Crates et al., 2016; Jack, 2016) has also reported variation between both species and individuals in their use of feeding stations.

THE USE OF GARDEN FEEDING STATIONS AND GARDEN TYPE

The extent to which garden feeding stations are used is shaped first and foremost by where the garden is located; put up a peanut feeder in a garden in the Scottish Highlands and you might just attract Crested Tit; place the same feeder in a garden in suburban Surrey and you won’t, but you might attract Ring-necked Parakeet. In addition to geography, the nature of the surrounding habitat will play its part. A rural garden in the east of England, surrounded by farmland, might receive visiting Yellowhammer and Reed Bunting Emberiza schoeniclus late in the winter when farmland seed supplies are very low, while one located next to a conifer plantation will be visited by Siskin and Coal Tit. We might therefore expect some general patterns to arise, indicating the likely garden bird community in gardens of different types and located within different landscapes. This is something that we have been able to examine by using data from BTO Garden BirdWatch (see Chapter 6 for more on this project). This work looked at the probability of occurrence in Garden BirdWatch gardens for 40 species (Chamberlain et al., 2004a). There were 26 species that showed a significant association with the habitat character outside of the garden and in most cases the probability of occurrence was higher in gardens located within rural habitats. For several species the probability of occurrence was very low in all but the most rural habitats (Pied Wagtail, Rook, Siskin – winter only – and Yellowhammer). Interestingly, there were some species that were more likely to occur in gardens located within more urbanised habitats, including: Black-headed Gull (medium and large gardens), Feral Pigeon, Magpie (large gardens), Starling and House Sparrow. Several species showed obvious peaks in their occurrence at intermediate scores, suggesting an association with suburban gardens; these included Coal Tit, Long-tailed Tit Aegithalos caudatus, Nuthatch, Treecreeper Certhia familiaris, Jay Garrulus glandarius, Magpie (medium gardens) and Bullfinch Pyrrhula pyrrhula.

FIG 29. Black-headed Gulls are occasional visitors to garden feeding stations, rarely seen in summer when they have their characteristic chocolate brown heads, but sometimes forced to turn to gardens during periods of poor winter weather. (John Harding)

THE USE OF GARDEN FEEDERS IN RELATION TO WIDER AVAILABILITY OF FOOD

As we have just touched on, the use of garden feeders by seed-eating birds is likely to be influenced by the availability of favoured seeds within the wider environment. This is likely to be particularly relevant in relation to tree seeds, since many tree species produce very large numbers of seeds in some years but not others – a process known as masting. In mast years, the very large volume of seeds produced is thought to saturate seed predators with an over-abundance of food, leaving some seeds to germinate untouched. Since the seed crop produced the following year is typically very much smaller, the populations of seed predators are prevented from growing sharply, leaving the balance in favour of the trees when they next come to produce a bumper crop. A number of studies have shown that the population size and breeding performance of various bird species is linked to these masting events. But can such masting events influence the extent to which seed-eating birds make use of garden feeding stations?

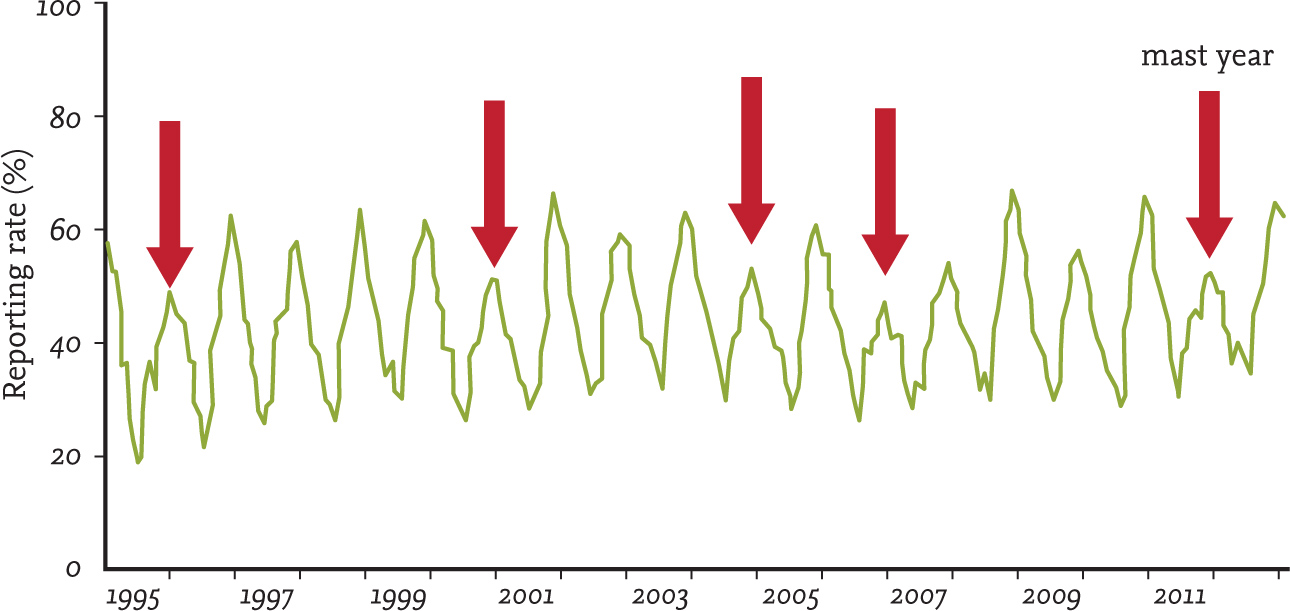

This is something that has been investigated by using the garden bird datasets collected by the BTO through the Garden Bird Feeding Survey (for Beech Fagus sylvatica) and Garden BirdWatch (for Sitka Spruce Picea sitchensis). Chamberlain et al. (2007a) found that the probability of occurrence at garden feeding stations for seven beechmast-eating species (Great Spotted Woodpecker, Woodpigeon, Great Tit, Coal Tit, Nuthatch, Jay and Chaffinch) was significantly lower in those years when a masting event occurred. A similar pattern was found for Siskin and Coal Tit in relation to Sitka Spruce, a species known to produce mast crops at intervals of three to five years (McKenzie et al., 2007). The seed and cone crops produced by these trees are synchronised, within a species, over very large areas, which is why such patterns can be seen very clearly in the BTO datasets. As we will see in the final chapter of this book, Sitka Spruce has been of particular importance to Coal Tit and Siskin populations within the UK, with its small seeds (relative to those of other conifers) proving particularly valuable. The availability of conifer seed to small birds may also be shaped by weather conditions, since it is known that conifer cones open to release their seed on dry days but remain firmly closed when it is wet (Harris, 1969). This may explain the apparent increase in bird-feeder use witnessed in my own garden on damp days during late winter, when Siskin numbers generally peak within gardens.

FIG 30. Coal Tits make greater use of garden feeding stations in those winters when the Sitka Spruce seed crop is poor. Data reproduced from BTO Garden BirdWatch with permission.

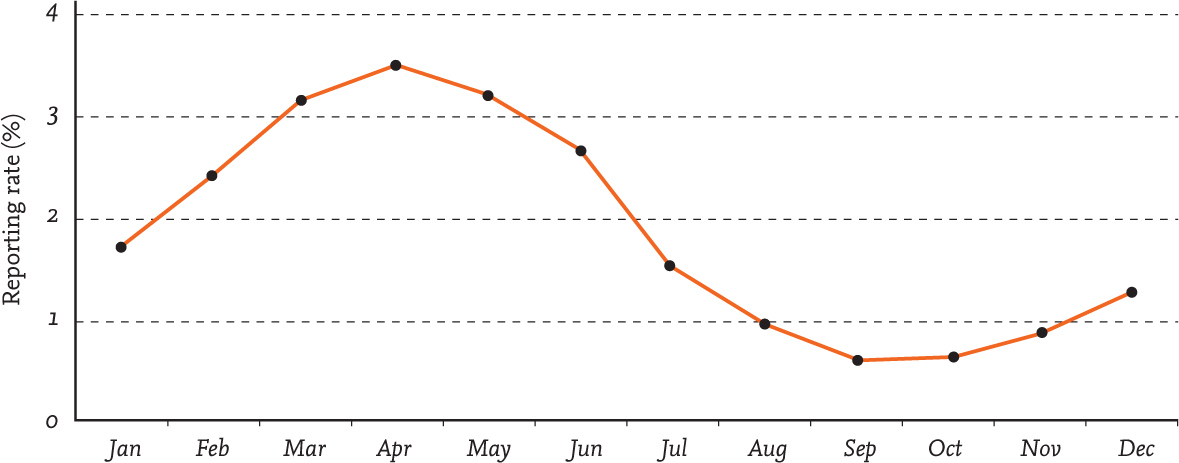

There is also evidence of a movement into (largely) rural gardens during the late winter period, with farmland buntings and finches showing their annual peak in garden use at this time according to data from BTO Garden BirdWatch (see Figure 31). The late winter period is known to be a difficult time for seed-eating birds using farmland habitats, the loss of overwinter stubbles leaving a ‘hungry gap’ in food availability (Siriwardena et al., 2008), something that may prompt the birds to aggregate in patches of habitat where seeds can still be found (Gillings et al., 2008) or to move out of farmland and into other habitats (Gillings & Beaven, 2004). Examination of data from the Winter Farmland Bird Survey (Gillings & Beaven, 2004), alongside that from BTO Garden BirdWatch for the same weeks, is suggestive of a movement out of farmland and into gardens for Goldfinch and potentially other species (Figure 32). Further supporting evidence comes from the long-running Garden Bird Feeding Survey. This shows an increase in the use of gardens by Reed Bunting and Yellowhammer during the period of greatest agricultural intensification (Chamberlain et al., 2003; 2005); although not supported by formal statistical tests, it could reflect increased use of garden foods because of a decline in seed availability within wider farming landscapes.

FIG 31. The use of garden feeding stations by Yellowhammers peaks during the second half of the winter, a period during which farmland seed supplies are at their lowest. Data reproduced from BTO Garden BirdWatch with permission.

Work carried out in France supports the value of rural gardens for farmland birds during the winter months. Using data from the French Garden Birdwatch scheme, Pierret & Jiguet (2018) looked at garden use by farmland bird species along a gradient denoting agricultural intensification. Garden feeders located within intensively cultivated landscapes were found to attract more birds, with this relationship strongest for truly farmland species. The pattern became more pronounced as the winter progressed, suggesting that as farmland seed supplies become depleted, so farmland birds increasingly turn to gardens.

One scarce farmland bird for which a number of rural gardens may be of particular importance within the UK is the Cirl Bunting Emberiza cirlus, whose small Devonshire population makes regular use of garden feeding stations in the south of the county during the winter months. Of course, to fully understand the role that gardens play in the ecology of bird communities breeding within farmland, we need to be able to track their individual movements, something that is becoming increasingly possible through the use of emerging technologies, such as PIT tags. The pull of garden feeding stations has wider implications for those involved in survey work, particularly during the winter months. Ask any volunteer who has participated in bird atlasing during the winter months, and found themselves in an area of open country, and they will tell you how it is the rural gardens and their feeding stations that are the place to look for small birds. This effect has been studied experimentally through work carried out in Maine, US, where researchers were testing a bird survey technique widely used in the breeding season and involving an observer making a series of stops along a linear and driven route. At each stop the observer would carry out a ‘point count’ noting the bird species recorded during a fixed time interval before moving on to the next stop. By examining the densities of birds recorded at stops with and without a feeding station, the researchers found that for five species densities were higher at stops with feeding stations. As well as this, presence of the food appeared to influence the birds’ habitat selection, pulling them into edge habitats.