Полная версия:

Garden Birds

FIG 19. Sunflower hearts, with their high edible oil content, are very popular with garden birds like Goldfinch. The popularity of these seeds has as much to do with Russian agronomists as it does with American entrepreneurs. (John Harding)

Sunflower seeds and their oil have a range of market uses, with the black-husked oilseed type a staple for bird food; this was introduced into the UK in the 1970s. Sunflower hearts were first introduced to the UK market during the early 2000s, their use proving popular with both wild birds and with the people putting out food. Unlike black sunflower seeds, hearts are already de-husked so leave less mess under bird feeders that then needs to be cleaned up. The lack of a husk also reduces handling times for feeding birds, which makes the hearts energetically more attractive that the traditional black sunflower seeds. At 6,100 kcal per kg, the calorie content of sunflower hearts is better than that of peanuts (5,700 kcal per kg); because the hearts have been de-husked, by weight they are also significantly higher in kcal than black sunflower seeds (5,000 kcal per kg).

Peanuts

Peanuts, also known as monkey nuts or groundnuts, are the edible seeds of Arachis hypogaea, a cultivated leguminous plant originating from a genus that developed in southwest Brazil and northeast Paraguay, where the most ancient species in the genus still grow. Available evidence suggests that Arachis hypogaea itself emerged within the hunter/cultivator communities present in Peru and/or Argentina. Peanut shells dated to 1800–1500 BCE have been excavated from sites near Casma and Bermejo in Peru and in the High Andes of northwest Argentina. There is also evidence of early presence in China, suggesting that mariners from China visited the South American region and returned home with peanuts. Evidence from shipwreck remains off the South American coast adds further support to this hypothesis.

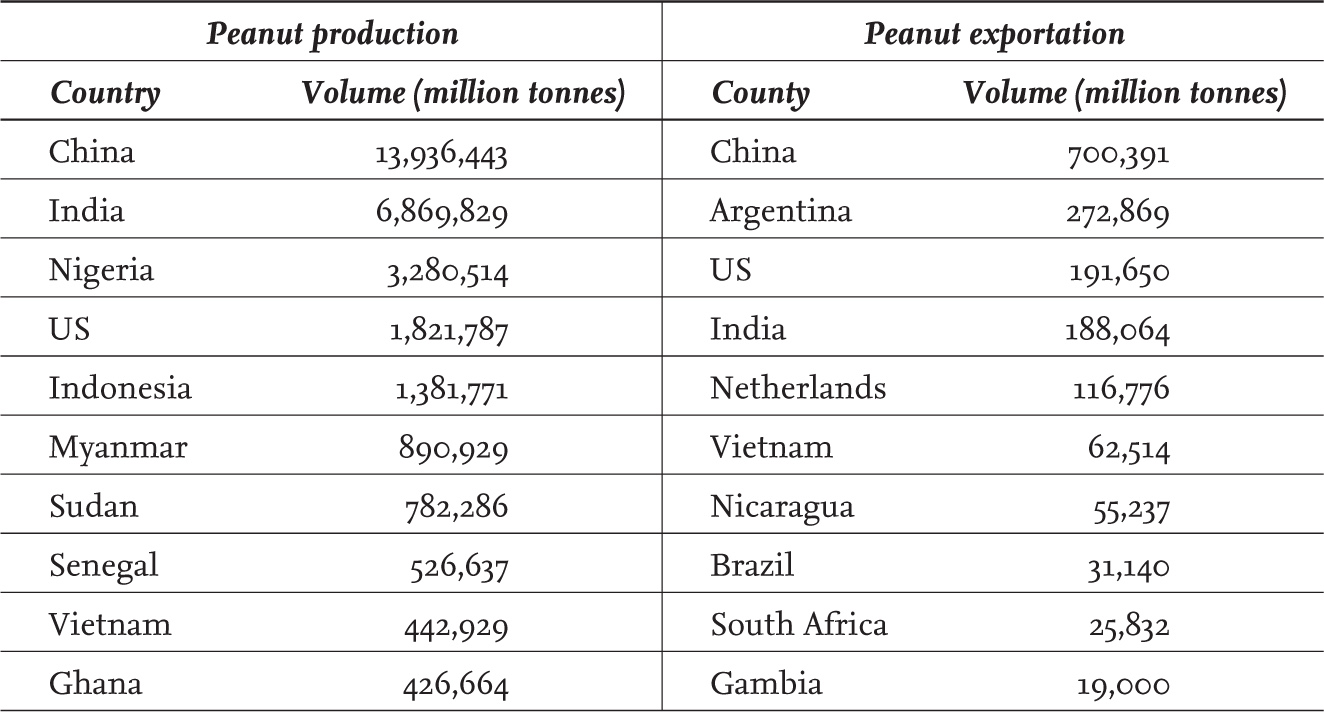

In recent history, and up until the 1960s, peanut production was dominated by countries within the sub-Saharan region of Africa, but this changed rapidly following low yields, change in domestic policies and a reduction in market pull (Pazderka & Emmott, 2010). Over the same period (see Table 2), China became the dominant producer of peanuts, securing 37 per cent of the producer market share by the mid-2000s and benefitting from internal agricultural reforms and the development of its market economy. Production within some countries (e.g. India and Indonesia) is more targeted towards internal markets than export and there has also been an interesting development in the market for value-added prepared peanuts, which is why the Netherlands features so prominently in the export table.

TABLE 2. Peanut production and exportation at a global scale, 2001–07. Data from Pazderka & Emmot (2010).

Peanuts can vary in their quality, both between regions and in relation to local climatic factors. There is, for example, a general acceptance that those produced in China are of better quality than those originating in India because of the higher oil content that they contain. With more than 100 countries cultivating peanuts, of many different varieties, it is easy to see how the wild bird food peanut market now has global reach. As we will discover in Chapter 4, peanuts are not without their problems; the presence of aflatoxin is a major threat to the market and to peanuts destined for wild bird food. In some years and areas, whole crops can be lost because of the presence of aflatoxin – which is toxic to both humans and birds – and this is why, for example, US producers can spend in excess of $27 million annually in order to ensure that their peanuts meet the agreed standards for aflatoxin control.

Peanuts were once a staple at UK garden feeding stations, initially presented in mesh bags, and to some extent still are for many of those who feed wild birds. However, the development of new seed mixes and the popularity of sunflower seeds and hearts with both birds and bird feeders have reduced their prominence. It is not unusual for those providing food to comment that the peanuts in their feeders often go largely untouched, except for visiting Great Spotted Woodpeckers and occasional Nuthatches Sitta europaea.

Seed mixes

A wide range of seed mixes is now available for use in feeding wild birds and these can vary greatly in their composition. In addition to seed-only mixes, some also include fat- or suet-based material or have invertebrate protein or fruit added to them. Watch a Greenfinch feeding at a feeder containing a seed mix and you’ll soon discover that the bird will typically select certain seeds and drop others. This pattern of selection reflects the fact the different seeds and grains vary in both their nutritional content and in the time required to process them. A feeding bird is seemingly able to balance these two components and make an appropriate selection.

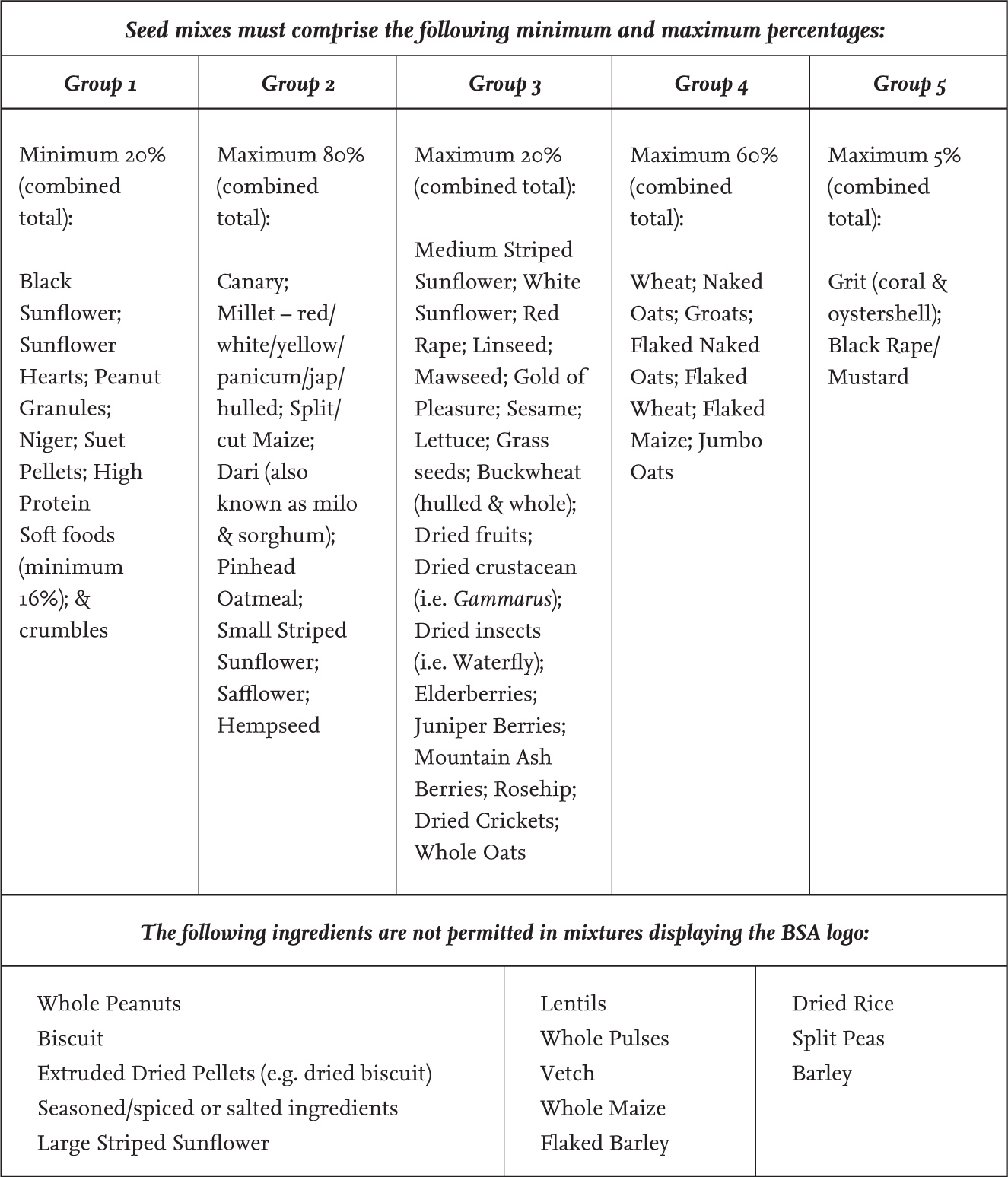

Recognising the different nutritional content of different types of seed, and wishing to secure an advantage in what is a highly competitive market, a number of wild bird care companies have signed up to the Birdcare Standards Association, an industry body that is governed by a set of guidelines. The guidelines for wild birdseed (see Table 3) effectively identify certain foodstuffs as being largely unsuitable. These, which include buckwheat and whole oats, sometimes feature prominently in cheaper seed mixes, where they effectively provide a bulking agent, which is little used by the birds. When looking for a seed mix, you often find that you get what you pay for, the better-quality mixes commanding a premium. However, you also need to consider the species that will be feeding on the mix; if, for example, the main recipients will be House Sparrows, then a mix with larger seeds and grains is likely to be better used than one which is made mostly of smaller seeds which the sparrows find difficult and time-consuming to process.

TABLE 3. The Birdcare Standards Association sets the following compulsory standards for seed mixes carrying the Birdcare Standards Association logo.

Niger

The small seeds of Niger were originally used to produce a cooking oil by peoples living within eastern Africa, and cultivation probably first occurred in the Ethiopian highlands. The seed was renamed ‘Nyjer’ in the US, in part to clarify its pronunciation and avoid unfortunate associations with a similar-looking slang word, being registered as a trademark of Wild Bird Feeding Industry, a now well-established US company, in 1998. It is sometimes referred to, incorrectly, as ‘thistle’ seed. As a flower, Niger had certainly been introduced to British gardens by 1806, and the species has been known in the wild since 1876. There is a suggestion from national botanical surveys that its occurrence in the wild is increasing, perhaps because of its use in bird food. As a commercial crop, Niger is mainly grown in India, Ethiopia and – to a lesser extent – Myanmar, underlining the global scale of production that ends up on UK garden centre shelves.

Use as a supplementary food for wild birds came rather later, the seed starting as something of a niche ‘conditioning’ product used by cage bird enthusiasts. It was known to be popular with American Goldfinch Spinus tristis and Pine Siskin Spinus pinus in the US in the 1960s, and it was the association with Goldfinches here in the UK that helped its popularity to increase. The seed’s small size leads to it being favoured by fine-billed species like Goldfinch and Siskin, with larger-billed species finding it too delicate to bother with. The small size also requires the use of a special ‘nyjer feeder’, whose small feeding ports prevent the seed from flowing out of the feeder and onto the ground – which is what happens if you inadvertently put the seed into a standard feeder. Initially, it seems that the provision of Niger seed at garden feeding stations encouraged the arrival of Goldfinches, with some participants in the BTO Garden BirdWatch scheme commenting on how they had never had visiting Goldfinches until they started provisioning the seed. Others, however, failed to attract them to Niger, even where it was provided alongside other foods at garden feeding stations. One of the interesting patterns of Niger use by Goldfinches appears to be the move away to sunflower hearts over recent years; this may be linked to the decline in UK Greenfinch populations following the emergence of finch trichomonosis (see Chapter 4) and the release of Goldfinches from competition with this larger and more dominant species. Niger seed may still be an important food for Siskin and Lesser Redpoll Acanthis cabaret, the latter species now being seen more commonly at UK garden feeding stations.

FIG 20. With their fine bill, Siskins are one of the species to have taken to Niger seeds, though they seem to prefer sunflower hearts if these are available and there is little competition from larger species like Greenfinch. (John Harding)

Fat and suet products

Although highly variable in terms of their content, a high-quality fat product may have in excess of 8,500 kcal per kg, something that makes these products particularly attractive for use during the winter months. Fat- and suet-based products come in a diversity of forms, probably the most familiar of which are ‘fat balls’ and square or rectangular blocks. Fat balls almost always used to be sold within plastic mesh netting, something that was occasionally responsible for the death of a feeding bird, either caught by its foot or by its barbed tongue. Although a substantial number of netted fat balls are still sold (and purchased) within the UK market, there has been a welcome move towards un-netted fat balls.

Suet may also be presented in a pelletised form, something that is popular with Starlings, or in or around objects such as plastic sticks or coconut shells – popular with Blue Tits and Great Tits. Suet products often contain additional material, perhaps added to increase the range of species that will take it, to broaden its nutritional composition or to secure a marketing advantage. These include seeds, nuts, berries and insect protein (typically mealworms). Suet products may also contain ash in variable quantities, added in order to bind the material together and to reduce the chances of the product breaking down. Again, the Bird Care Standards Association has a set of rules relating to this type of product, though these are geared more towards the source of the fat, rather than the composition of the product or content of additional material. The standards are as follows:

i) suet should be derived from animals that have received ante- and post-mortem examination by veterinary officers and found to be fit for human consumption;

ii) all suet should be processed at a fully licensed and approved EU or US abattoir, and

iii) any suet products that are blended with peanuts, either in whole or granular form, must use peanuts that contain a nil detectable aflatoxin level.

Live foods

The term ‘live foods’ refers to the provision of insects, typically mealworms and wax worms, which are bred specifically for this and the wider pet food market. These may be provided alive or, more commonly, in a desiccated form. Mealworms are not worms but larvae of darkling beetles belonging to the genus Tenebrio. Within the UK it is the larvae of the Yellow Mealworm Tenebrio molitor that are most commonly used as food for wild and aviary birds, captive reptiles and amphibians. The smaller sized larvae of the Dark Mealworm Tenebrio obscura are sometimes used. As their name suggests, mealworms have a long association with human beings, occurring as pests of grain and other cereal products. Mealworms are fairly easy to rear, both at home and commercially, and a number of companies are now involved in the large-scale farming of these beetles, producing insect protein not just for wild birds and the pets already mentioned but also as a contribution to cat and dog food products and, looking to the future, human foods (Grau et al., 2017).

FIG 21. Mealworms are often very popular with Starlings, Robins and Blackbirds, with individual birds quickly learning to exploit them where they are offered. (John Harding)

Wild birds seem to prefer live mealworms, presumably because they attract attention by their movements, but probably because they are far closer in their composition to wild caught food. Mealworms have a high protein (13–22 per cent) and fat (9–20 per cent) content and are also a source of polyunsaturated fatty acids, essential amino acids and zinc. Perhaps surprisingly, they have a significantly higher nutritional value than either beef or chicken.

Other foods

Bread appears to be a popular food with householders, perhaps because it provides an opportunity for them to direct unwanted crusts or stale slices towards other creatures perceived to be in need of sustenance. Its nutritional value is, in the context of garden birds, unclear. Bread was by far the commonest food provided by householders who responded to a questionnaire survey carried out in Cardiff in the 1980s (Cowie & Hinsley, 1988a), with c. 90 per cent of respondents provisioning bread in both winter and summer. Galbraith et al. (2014) found bread to be the most commonly provisioned food in their study, estimating that the equivalent of more than five million loaves was put out by New Zealand residents annually.

FIG 22. A small number of UK householders put out meat scraps or even whole carcasses for visiting Red Kites. (Jill Pakenham)

Apart from the small number of householders nationally who provide meat for visiting Red Kites Milvus milvus, only a small proportion of the kitchen scraps fed to wild birds here in the UK include meat. The situation is very different in Australia where the provision of meat is fairly typical. This reflects clear differences between the main groups of birds visiting garden feeding stations here in the UK (seed-eating species) and in Australia (omnivorous species, such as Laughing Kookabura Dacelo novaeguineae, Australian Magpie Gymnorhina tibicen and Grey Butcherbird Cracticus torquatus). As we’ll see later in this chapter, the provision of meat has potential implications for wild bird health.

In parts of North America, sugar solution is used to attract and feed hummingbirds. Typically made from one-part cane sugar to four-parts water, the solution is seen as a supplementary food rather than a replacement for the sugars that these tiny birds would normally secure from flowers. While those hummingbirds tested appear to be more strongly influenced by the position of a food source rather than its colour, many feeders are red in colour because this is perceived as increasing their attractiveness to hummingbirds. Once a food source has been identified, colour may act as an important discriminator stimulus and it may be that individuals learn to associate this colour with these new nectaring opportunities (Miller & Miller, 1971). The increasing use of hummingbird feeders has been linked to the changes in the range of Anna’s Hummingbird Calypte anna, a species that now overwinters and presumably breeds at more northerly latitudes than it did a few decades ago. Examination of Project FeederWatch data (see Chapter 6 for more on this project) demonstrates that more participants in the large-scale study now offer sugar solution in hummingbird feeders than once did, though it is unclear whether the increase in feeder provision has driven the range expansion of this hummingbird species, or the range expansion has led to more people putting out hummingbird feeders (Greig et al., 2017).

THE NATURAL FOODS AVAILABLE WITHIN GARDENS

Invertebrates

Many of the birds making use of garden feeding stations also feed on invertebrates; for some garden birds, such as Wren, it is the insects and spiders found within the garden that are the food of choice. Because species like Wren usually ignore the food provided at bird tables and in hanging feeders, their presence in the garden can be easily overlooked. We don’t know a great deal about how the features present within gardens and across the wider urban environment shape the community of invertebrates that is found there. While there are some obvious relationships, others are masked by the complexity of the many microhabitats present and the influence of components within the wider landscape. Work carried out as part of the Biodiversity in Urban Gardens project (BUGS) underlines the difficulties in seeking to identify relationships between invertebrate abundance and particular features (Smith et al., 2006a).

The plant species growing within gardens will have a shaping influence on many of the invertebrate species present, not least because the plants provide many of the feeding opportunities that such invertebrates require. A typical garden flora will almost certainly comprise a mixture of native and non-native species, and the latter may prove unsuitable for insects because of their chemical composition or structural characteristics. Things may not be as bad as you might assume, however, since the chemistry of individual plant species tends to be fairly similar within a family and many of the non-native plants introduced into UK gardens belong to families that also contain a native component. The BUGS project revealed that of the 1,166 plant species recorded in 61 Sheffield gardens, 70 per cent were non-native; however, at the family level, just 36 per cent of the families were alien in origin (Smith et al., 2006b).

FIG 23. While some hoverfly species avoid being predated by mimicking less palatable species, other garden-visiting flies may be taken by Spotted Flycatchers and other bird species. (Mike Toms)

Despite this, there is evidence from work carried out in the suburban landscapes of southeastern Pennsylvania, US, that native planting can be better for both invertebrates and the birds that feed on them (Burghardt et al., 2008). Karin Burghardt and colleagues looked at a number of avian and lepidopteran community measures across paired suburban properties, one property in each pair being planted with entirely native plants and the other with a conventional suburban mix of natives and non-natives. The native-planted properties were found to support significantly more caterpillars and range of caterpillar species and had a significantly greater abundance, species richness and diversity of birds; they also had more breeding pairs of native bird species.

The structure of plants can be an issue where the cultivars presented in garden centres and plant catalogues are divergent from native forms. For example, the ‘double cultivars’ of certain flower forms, which prove popular with gardeners because of their extended flowering season and novel appearance, are less suitable for nectar-feeding insects and they also set less seed. If flower selection and form reduces opportunities for invertebrates within the garden, then it will also reduce opportunities for insect-eating birds. One consequence of this can be seen in the generally lower productivity of tit species within the urban environment. Great Tits and Blue Tits feed their young on small caterpillars and appear to struggle to find enough of these in many urban and suburban gardens (Cowie & Hinsley, 1987).

FIG 24. The larvae of craneflies and other soil-dwelling invertebrates taken from garden lawns are important for Starlings and other species. (Jill Pakenham)

It is also important to recognise the widespread use of insecticides and related compounds in gardens, since these have the potential to both reduce prey availability and to enter the food chain, where problems may then occur. More widely within the built environment there is the risk from pollution, such as with heavy metals (see Chapter 4), which can also impact on the availability of invertebrates and alter the composition of the prey communities available to foraging birds (Eeva et al., 2005).

Fruits, seeds and nectar

Garden plants can also provide food for visiting birds more directly, through their fruits and seeds; in fact, many plants rely on birds to act as dispersal agents for their seeds, offering a nutritious fleshy fruit to attract the bird to take the seed. For example, the natural foods taken by garden-wintering Blackcaps include the berries of Cotoneaster, Honeysuckle Lonicera, Holly Ilex aquifolium, Mistletoe Viscum album and Sea-buckthorn Hippophae rhamnoides. Blackcaps have also been reported feeding on the seeds of Daisy Bush Brachyglottis greyi (Hardy, 1978). The different fruits and seeds become available at different times of the year, though predominantly from October through to January, and this can alter the shape of the bird community visiting gardens. The movement into gardens of wintering Redwing, Fieldfare and Waxwing may reflect the availability of favoured berries in gardens and their scarcity elsewhere. It has been noted, for example, that the timing of hedgerow cutting within the UK’s arable landscapes may remove large quantities of the berry standing crop from the wider landscape, leaving gardens as an important resource (Croxton & Sparks, 2004).

Some of these berries are favoured over others and in some cases a long fruiting season, such as in Holly, can suggest that the berry isn’t particularly favoured by visiting birds, only being eaten once other options are no longer available. In addition to the differences seen between different plant species, the nutritional characteristics of individual fruits may also vary with season. In many berries, the water content of the pulp decreases as the season progresses, while the average lipid content increases. Berry colour may be used as a signal, alerting berry-eating birds to the reward on offer, and there is evidence that birds may select fruits of a particular colour because of their nutritional value. Some bird species appear to select fruits with a high anthocyanin content; anthocyanin is an antioxidant and berries rich in this pigment tend to be black in colour or ultraviolet reflecting. Work on Blackcaps indicates that individuals actively select for anthocyanins in their diet and that they use fruit colour as an honest signal of anthocyanin rewards when foraging (Schaefer et al., 2007).

The consequences of the variation seen in fruits leads to species-specific preferences within the bird species that feed upon them. A series of studies by David and Barbara Snow has highlighted some of these preferences. Mistle Thrush, for example, was found to favour sloes over haws, while the preference was reversed in both Redwing and Fieldfare. Song Thrush Turdus philomelos showed a clear preference for Yew Taxus baccata, Elder Sambucus nigra and Guelder Rose Viburnum opulus, and the apparent avoidance of rosehips, while Blackbird was found to be fairly catholic in its tastes (Snow & Snow, 1988). Blackcaps make use of smaller berries in gardens, such as those of Cotoneaster conspicua (Fitzpatrick, 1996a), reflecting their almost entirely frugivorous diet (when fruit is available) within the Mediterranean wintering area (Jordano & Herrera, 1981), although it is interesting to note the importance of supplementary foods presented at garden feeding stations highlighted by Plummer et al. (2015) and explored later in this chapter.

FIG 25. Berry-producing garden shrubs can be very popular with Mistle Thrushes and other visiting thrushes, together with Blackcaps and Waxwings. (John Harding)