Полная версия

Полная версияПозитивные изменения. Том 2, №4 (2022). Positive changes. Volume 2, Issue 4 (2022)

Данная шкала значима как при внедрении в модель соседского центра, так и для движения, воронки роста статуса каждого жителя и допущения наличия потенциала, таланта, особенностей в каждом. Это позволит обеспечить максимально возможный спектр вовлечения и создания условий развития жизни на территории, в том числе всех форм и направлений предпринимательской инициативы в самом широком смысле, с одновременным снижением рисков развития латентных социальных проблем.

9. Приоритет социальных проектов – приоритет коммерческих проектов.

Сразу важно отметить намеренно использованную ложность данного противопоставления на шкале. У этих стереотипно полярных позиций есть одна общая и принципиально важная как для центров, так и для движения основа – предпринимательская инициатива. В какой сфере в данный момент в данной локации инициатива предпринимателя будет проявлена – значения не имеет, важнее чтобы ее реализация могла быть успешнее благодаря капиталу сообществ на базе центров и/или движения. То есть главное – чтобы горожане в принципе могли самоопределяться как акторы, субъекты социальных и экономических процессов, агенты и лидеры позитивных изменений.

10. Ценности открытости к новому, инновационность – ценности консерватизма.

Последняя шкала – своеобразный тест на готовность к устойчивому развитию – через позитивные изменения, обучение, открытость к новым решениям, способность к принятию новых проблем, перемен, технологий, взглядов на мир и его возможные траектории развития. Может показаться очевидным важность приоритета данной ценности, но при этом, когда в рамках онлайн-исследования клубов на базе движения был задан вопрос о потребности в обучении и интересах развития, большая часть ответов выражала отсутствие подобного запроса, что показывает на проблемы для трансформации, но не меняет сути выявления близости и возможности перевода текущих социальных запросов, в том числе оформленных в движения, в запрос на создание соседских центров.

Таким образом, по мнению автора публикации, озвученный подход и использование подобного рода шкал может помочь на уровне «чек-апа» инициативным группам в понимании и самоопределении в отношении развития соседского центра на своей территории. А затем, на основе либо уже существующего предложения и моделей соседских центров, либо авторского решения начать строить свою «столицу».

“Neighborhood Capital”: A Neighborhood Center as the Key to Shaping Cities and Communities

Vladimir Vainer

DOI 10.55140/2782–5817–2022–2–4–56–65

The topic of neighborhood centers has been a focus of research for more than 100 years. These days we see another rebirth of neighborhood centers. Leading development companies are making social investments in this element of the urban fabric. In this article, we reflect on the vision of neighborhood centers, their role, and their search for a development model – something you need to know before you start building your “little neighborhood capital.”

Vladimir Vainer

Director of Positive Changes Factory

THE SCIENTISTS' VIEW

The idea and concept of neighborhood centers as the key component of life development in the cities and villages in Russia has been fully revealed in recent decades in the works by Elena Shomina and Sergey Kuznetsov, Peter Ivanov, Vladimir Vainer, Svyat Murunov, as well as in the materials of Applied Urbanistics Centers and other experts and practitioners, first of all heads of neighborhood centers created by developers in new urban neighborhoods.

In the international scientific discourse, the topic of neighborhood centers has been around for more than 100 years. According to Peter Ivanov, an urbanist and sociologist at the Civil Engineering Laboratory, author and editor of the Telegram channel “Urbanism as the Meaning of Life,” “many think that neighborhoods were invented by Le Corbusier.” Those who have read Glazychev believe that neighborhoods were invented by Clarence Perry. In fact, neither is true. Microdistricts were invented by William Eugene Drummond, whom Wikipedia describes as “a Prairie School architect[69].”

Architect William Eugene Drummond proposed the concept of a Neighborhood Unit, where a unit is understood as “part of the whole.” Drummond pointed out that the modern city (with its major projects now more than a century old) needs to recreate the social and political relations among its citizens and, consequently, the need for new special infrastructure. According to Peter Ivanov, Drummond took sociologist Charles Cooley's concept of the “primary circle of social relations” as the basis and focused attention on the neighborhood unit, the environment in which that very circle of relations – family, friendship, neighborhood – is preserved and maintained.

“Each neighborhood unit, according to Drummond, consists of low-rise apartment buildings, an elementary school, a playground and a neighborhood center,” Ivanov notes. In modern parlance, the Drummond neighborhood center is the “little capital” of the neighborhood, an amalgamation of a wide variety of functions that are still characteristic of the modern neighborhood center – a club, a place for meetings and gatherings, sports center, and so on.

In contrast to the modern developers' prevailing view of the neighborhood centers, Drummond saw them as a major tool for providing individuality and, following that, political subjectivity to the city neighborhoods. And then, each neighboring unit would create the fabric of the city itself, with business spaces and centers, parks, squares, and promenades emerging at the “junctions between the neighborhood units.”

Peter Ivanov notes that this concept became so popular that Drummond's terminology was borrowed in the 1920s by Robert Ezra Park, the founding father of the Chicago School of Sociology, who also argued that neighborhoods were the foundational core of the urban fabric. And by the 1930s, under the influence of the Chicago School sociologists, Clarence Perry offered his own understanding of neighborhood units, shifting the focus away from the political role of neighborhood centers[70]. It was Perry's approach, as Peter Ivanov notes, “that was creatively reworked in the USSR,” which resulted in the neighborhoods as we all know them.

From practically the only Russian-language review of Drummond's concept by Peter Ivanov, the reader can draw several important conclusions for this material:

• Neighborhood centers are a part of the neighborhood's living routine, lost during the “creative reworking,” and this might be a good time to bring this element back into the urban fabric;

• Neighborhood centers are one element of the neighborhood unit, creating a holistic structure and conditions for self-actualization of each resident, preventing stigmatization of certain groups of residents and unlocking the potential of neighborhood communities;

• Neighborhood centers create an identity for each unit of an entire city, providing (with sufficient development and scale of amalgamation) the territorial, social, and political subjectivity that we can already observe in a number of cases of the development of the Territorial Public Self-Governments or community foundations.

THE DEVELOPERS' VIEWPositively, these findings are reflected in many ways in today's vision of the role and purpose of neighborhood centers by the leading development companies. This can be seen, in particular, from the agenda of most large-scale and regular professional events, such as the annual international conference “Factory of Spaces.” The organizer of the conference, the Blagosfera center, brings together community space owners and managers every year with a mandatory separate event dedicated to neighborhood center development. In the fall of 2022, such an event was the Neighborhood Center Leaders Session of development companies, organized in conjunction with the Positive Changes Factory.

Its key topics were those of the vision and the role of neighborhood centers, as well as the search for a neighborhood center development model that is most adequate to the contemporary situation.

According to Irina Gontarenko, Project Manager of Neighborhood Centers at Brusnika Company, each center is an element of the neighborhood's social infrastructure for self-actualization of the residents, establishing a community within itself and stimulating its development[71]. The roles of the community and the developer are clearly spelled out and distributed. Brusnika participates in creating the community, setting the development vector, moderating processes, assisting in managing controversial situations and providing financial support at the initial stage (the first year). The community contributes by community development activities, providing content for events, creating and implementing projects.

The community center concept presented by GloraX[72] Head of Special Projects Olga Nerusheva emphasizes that a developed local community improves the environment and speeds up the decision-making process regarding the development of the space. Community centers also stimulate the development of micro-businesses: “cafes, schools, lectures and workshops grant opportunities to discover and realize entrepreneurial talent. The more services are provided in a neighborhood and the more diverse they are, the more willing people are to buy housing there,” she says. According to her, it's all a value-added element. “The company's experts have already recorded cases where people from nearby houses first came to the co-working room, and then moved into the apartments of the developer's projects,” Olga Nerusheva explains.

The general vector for unlocking potential is continued by the head of “We, the Neighbors” network of neighborhood centers[73] of the Seven Suns Development group of companies, Daria Mashevskaya. She singles out creating exclusive conditions for human and community development, providing local accessibility (being close by), aggregating all points of positive change in the neighborhood, and purposefully influencing the development of the area as the key goals of investing in neighborhood centers.

Disclosing these goals, Daria Mashevskaya describes the objectives of introducing and uniting people sharing common interests, providing support and resources for the development and solution of problems formed within the community, including those that coincide with the values of the developer (customer). Thus, the expert notes, “we are moving from absent or sporadic communities to the creation of structured communities where residents are finding support from like-minded people, developing, working together to address urgent problems, and experiencing career growth and scaling.”

THE FOUR-STEP THEORYThe concepts described above, with their emphasis on bringing residents together and strengthening local communities, unlocking entrepreneurial potential, and aggregating all initiatives in the space of the “neighborhood capital,” in the opinion of the author of the publication, fit logically into the Four-Step Theory of Neighborhood Center Sustainability Development, presented in the 2019 methodological handbook “Setting Up a Neighborhood Center[74].”

Step One: Bringing locals together to share knowledge (meetings, lectures, seminars, tea parties, workshops, festivals, movie screenings, or readings). Already at the first stage – when people share with each other their discoveries, knowledge, and “life hacks,” e.g., survival tips for economically challenging conditions – we can see a process of transition from private knowledge to collective use, from private initiative to joint action, from private possession to shared use, etc., all with the “co-” prefix.

Interestingly, Elena Shomina, a key researcher of “neighborhood relations” also draws attention to this important characteristic in her work “Neighborhood Centers as an Element of Neighborhood Community Infrastructure”: “The community emerges as a result of the interaction between neighbor resident, their communication. The prefix “co-”, meaning common, shared, connects this concept with the terms “communication” and “coownership”. The latter has become especially important in modern Russian apartment buildings since the privatization of housing and the emergence of the concepts of “common property” and “common household needs[75].”

Neighborhood (community) centers are commonly used by their community as a place for:

• joint celebration of events significant to the local residents;

• joint meetings of the residents on various issues;

• joint use of the premises for local clubs and various volunteer associations;

• joint collection, storage, and sharing of local history (a neighborhood museum function), etc. The manifestation of the prefix “co-” means the transition to the second level.

Step Two: pooling and sharing resources. This step is where usually collaborative crowdfunding and sharing projects are usually launched, ensuring the transition to the next level.

Step Three: launching a wide range of micro-entrepreneurial projects, both social and commercial (based on monetization of hobbies, new crafts, independent educational programs, training courses by residents for residents, etc.) on the basis of the neighborhood center. Such projects by residents and communities help improve the sustainability to monetize the center and move to the fourth level.

Step Four: The neighborhood center is a self-sustaining space, based on social cooperation, showcases of local goods and services for residents, schools and additional vocational education programs, an events calendar, and partnerships with outside companies.

The most exemplary synchronization of the four steps and the practice of a real neighborhood center was the model of the neighborhood center “We Are Neighbors,” tested and implemented in 2022 by Seven Suns Development. The model features a description of the potential development funnel for each participant in the life of the center – from a single neighbor, through uniting and launching initiatives, to the leader of the local circle, club, community, and so on. Interestingly, this funnel is also the basis for the season ticket system, which has become one of the sources of funding for the center. There is also great interest and anticipation caused by the intention of the leadership of the “We Are Neighbors” network to report in 2023 on the social impact of neighborhood centers and, in particular, the profile of the average participant in the neighborhood center activities – the neighborhood resident, with a focus on the dynamics and changes of the resident's subjectivity.

So now, a century later, we can once again be witnessing the blossoming of neighborhood centers based on social investment by development companies. And discovering new factors influencing the development of this institution given the contemporary specifics.

CRITERIA FOR SELECTING MODELS OF NEIGHBORHOOD CENTERS AND SELF-HELP CLUBSIn the early 2020s, the world entered the post-COVID time gaining a number of important elements of new social capital. In our country, one of them is a movement that grew organically on the basis of self-organization of citizens and communities, which took shape with the direct participation of a number of large NGOs and was called #WeAreTogether (#MYVMESTE) Since 2021, the movement has been managed by the Association of Volunteer Centers (AVC). The initiative is implemented differently in each region, but in 2022 AVC voiced its general aspiration – to create a network of self-help clubs for residents on the basis of this social capital[76].

Some of the experts engaged by AVCs for this transformation work to turn the movement into a club suggest that one possible vector of development could be organizing the residents' activity into neighborhood communities. Often initiated by residents, developers, or local government, they grow into neighborhood centers and their networks.

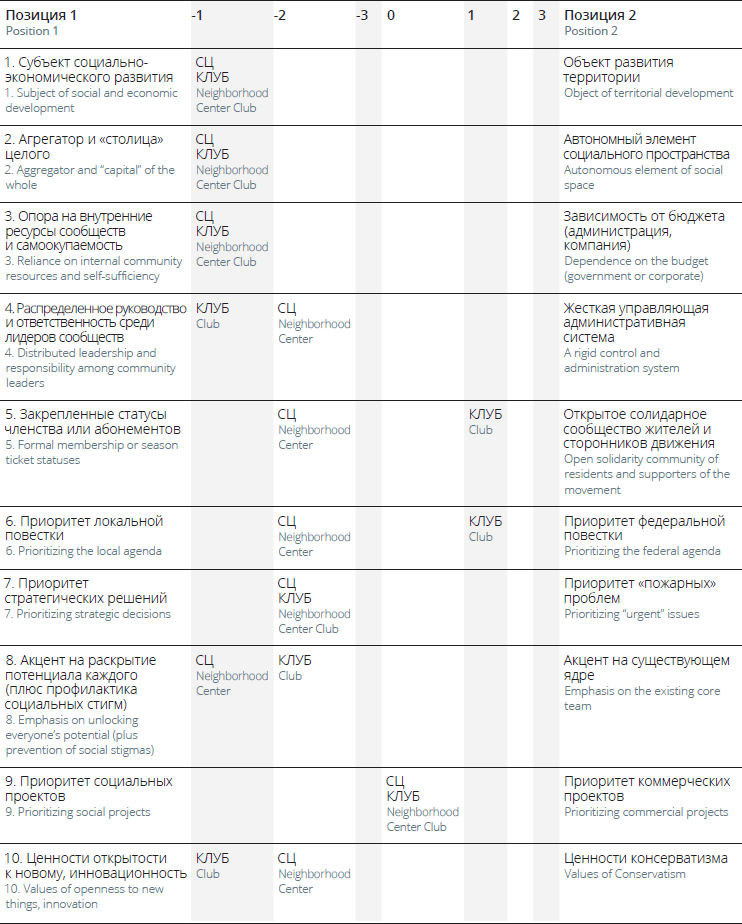

To see the touching points between neighborhood centers and potential clubs, let us analyze the conditions and possibilities for transforming the largest movement into the logic of neighborhood centers. We propose to do this on the basis of conditional rankings formed by experts in a study of clubs that have already appeared, and a review of various neighborhood center models.

1. The subject of socio-economic development or the object of territorial development.

The willingness to take responsibility and authority for the improvement of living standards in the local area is a clear indicator of readiness to set up a neighborhood center in one's neighborhood. This parameter can also easily be applied to assess the maturity of the local movement.

2. The aggregator and the “capital” of the whole or an autonomous element of social space. The existence of an understanding of the necessity and functionality of the neighborhood center as a space uniting all points of attraction in the neighborhood and at the same time a readiness to unite with other “capitals” of the urban fabric is another important indicator of the potential behind opening and developing a neighborhood center. This same characteristic was evident in the #WeAreTogether movement through 2022.

3. Reliance on internal community resources and self-sufficiency vs. Dependence on the budget (government or corporate).

Having the competencies to inventory, pool and manage the resources and capital of a neighborhood community with payback initiatives is a must for a neighborhood center in a social investment environment. However, for a movement, this component may prove to be the weakest link, since a movement in most regions is not considered in isolation from administrative tasks and resources.

4. Distributed leadership and responsibility among community leaders vs. A rigid control and administration system.

In the case of neighborhood centers, one can encounter the entire spectrum of formats between the two extremes, but in terms of the vision and role of centers, most experts believe it is more logical and strategically accurate to prioritize the first version of the ranking.

5. Formal membership or season ticket statuses vs. Open solidarity community of residents and supporters of the movement.

For an economically sustainable and socially subjective institution of the neighborhood center, it seems correct to develop a range of social statuses, formalized by various tools – from subscriptions for extra functionality to symbolizing the engagement through merchandize. Symbols of engagement in varying degrees of public or private manifestation may be sufficient for a broader movement, as, for example, in the practice of working to retain and increase the number of supporters of major charitable foundations.

6. Prioritizing the local agenda vs. Prioritizing the federal agenda.

It seems clear that in order to maximize the engagement of the neighborhood residents, it is important for the neighborhood center to establish and promote a local development agenda, in contrast to a movement, which has become primarily a response to a global challenge with local gaps in addressing these problems.

7. Prioritizing strategic solutions vs. Prioritizing “urgent” issues.

For the purposes of developing and/or transforming current practices, it is logical to shape the transition to “long-term” project and/or model solutions. Despite the seemingly obvious situation and immediate demands of the residents (especially in social networks and neighborhood community chats), and the specificity of work that is mostly aimed at helping “right here, right now,” the communities must be able to see the roots of problems and potential solutions based on the center and movement, to test solutions and further scale across the fabric of cities. In addition, they could change the scale from the local neighborhood level to citywide or greater, to discover and develop their own theory of positive changes for the entire region.

Table 1. Comparison of the model positioning of the neighborhood center and the clubs by the #WeAreTogether movement

8. Emphasis on unlocking everyone's potential (plus social stigma prevention) vs. Emphasis on the existing core team.

This ranking is meaningful both for implementing the neighborhood center model and for a movement, funneling the growth status of each resident and assuming that everyone has the potential, talent, and peculiarities. This will ensure the widest possible engagement and establish conditions for the improvement of living standards in the local area, including all forms and directions of entrepreneurial initiative in the broadest sense, while reducing the risks of latent social problems surfacing.

9. Prioritizing social projects vs. Prioritizing commercial projects.

It is important to note in advance that the juxtaposition of the two extremes on this scale. These stereotypically polar positions have one common ground, which is fundamentally important for both neighborhood centers and a movement: entrepreneurial initiative. It does not matter what field the entrepreneur's initiative will take place in, at the given time and location – it is more important that its implementation be more successful thanks to the capital of the community-based centers and/or movements. In other words, the key is for the citizens to be able to identify themselves as actors, subjects of social and economic processes, agents and leaders of positive change.

10. Values of openness to new things, innovation vs. Values of conservatism.

The last ranking is a kind of test of readiness for sustainable development – through positive change, learning, openness to new solutions, the ability to accept new problems, changes, technologies, views of the world and its possible development trajectories. The importance of prioritizing this value may seem obvious, but when the online survey of movement-based clubs asked about the need for training and development interests, most of the responses expressed lack of such demand, which shows obstacles for transformation, but does not change the essence of identifying proximity and the possibility of transforming current social demands, including those formalized into movements, into a demand for the establishment of neighborhood centers.

Thus, according to the author of the publication, the voiced approach and the use of this kind of rankings can help initiative groups during the “check-up” phase, to gain understanding and self-determination of the neighborhood center development in their territory. And then, based on either the existing proposal and neighborhood centers models, or the author's solution, they can start building their “capital.”

Исследования / Research Studies

Импакт-инвестирование: какие проблемы волнуют исследователей? Дайджест публикаций

Елизавета Захарова

DOI 10.55140/2782–5817–2022–2–4–66–81

Область импакт-инвестирования является местом схождения исследовательских интересов из широкого спектра научных дисциплин, и по мере развития рынка социального предпринимательства и рефлексии о том, как измерять социальный эффект, идет активная проблематизация происходящих внутри процессов. Какие темы в фокусе внимания исследователей рынка импакт-инвестиций, пойдет речь в нашем дайджесте публикаций, вышедших во второй половине 2022 года.

Елизавета Захарова

Аспирант факультета социальных наук НИУ ВШЭ

Одна из наиболее заметных тем, затрагиваемых в последних публикациях, – внимание к бизнес-этике и попытка разрешить этические проблемы, возникающие на фоне роста оборота импакт-инвестиций. Подчеркивается необходимость обеспечения соответствия практик социального обмена этическим стандартам и формирования оценки интеграции таких практик в проекты социальных предпринимателей. Помимо этого, актуализируются вопросы, связанные с решением проблем системного неравенства: появляются работы о том, как развивать инклюзивное участие в принятии решений для тех, кто является непосредственными выгодополучателями социальных инвестиций. Авторы некоторых публикаций выдвигают на первый план разговор о балансе между рисками и достижением вклада в решение социальных проблем. Фиксируется ускорение финансиализации рынка (т. е. роста экспансии финансового сектора) и укрепление роли благотворительности в снижении рисков импакт-инвестирования. Отдельный интерес в подборке представляет статья о том, как финтех-решения могут быть полезными в планировании и оценке импакт-инвестирования. В своем последнем отчете GIIN оценивает объем рынка импакт-инвестиций в 1,164 трлн долларов США и намечает две области для развития рынка: «зеленые» облигации и корпоративное инвестирование. Наконец, сохраняется тенденция среди исследователей предпринимать попытки по систематизации накопленной научной базы вокруг темы импакт-инвестирования, чтобы выделить в нем наиболее влиятельные исследовательские направления и тенденции и очертить круг для новых.