Полная версия

Полная версияEverything Begins In Childhood

“Where are those lazybones? Valery, Yura, run to the neighbor’s for benches and tables! Ilya and Yasha are already there.”

Yasha and Ilya were our cousins, Aunt Tamara’s sons. Some furniture was borrowed from our neighbors, the Fazildins, an Uzbek family. Their son, Allaudin, was our friend.

The entrance to their house was unusual – after opening the door, you entered a dark room with an earthen floor located under the house. Its other door led to the yard. After entering the yard, you could get to the house. Yura and I were very amused by this ingenious arrangement.

“Hey, Akhun, be careful, don’t run into the doorpost!” We heard Ilya’s voice as soon as we stepped from the sunny street into the darkness of the room.

Akhun was the nickname of our younger cousin, Yasha. The nickname didn’t have any special meaning; it was just reminiscent of the name of a statesman of our time, Akhunbabayev. Yasha was a rather unruly boy. Every time the brothers appeared in Grandpa’s yard, their loud squabbles and the clinking of broken glass could be heard. Yasha was indifferent to the nickname Akhun, but he couldn’t stand his other nickname, “Baldy.” Yasha’s head was quite often shaved for some reason. Maybe that’s why he got angry. Ilya tried his patience several times a day.

As we entered, the brothers were bringing in a big wooden table with crossed legs from the yard. It wasn’t too heavy, but it was too wide to fit through the doorway. The table got stuck, and Yura and I arrived just in time to help. Ilya began giving us instructions immediately:

“Sideways…now to the left… more, more… Stop! Can’t you see?”

Tables and benches traveled from one yard to another and back quite often. So, we boys, who were always entrusted with this work, had long ago become experts in pulling furniture through narrow doorways. Many words, whose meanings were very particular to the task, were used in the process – “diagonally,” “into a skid,” “lower,” “more to the side,” and the like. But it still wasn’t easy not to break these old but very necessary tables and benches and not to scratch doorposts. We were wet and tired after we had gotten that damned table outside.

“How many more?” I asked, waving flies away from my sweat-covered forehead. “Many. They want to clutter the whole yard with them,” Ilya mumbled. “I’ve seen mineral water delivered, but not too many bottles. We need to stash it, otherwise we won’t even get a taste.”

Tashkent mineral water, like many other things, was delivered to stores irregularly, and we boys liked it very much. Of course, we had to stash it so that at least at the wedding we could have as much of it as we desired.

We talked a bit about various tasty dishes, which we knew were already being prepared. Ilya’s thoughts somehow switched from this “tasty” subject to the bride.

“Have you seen her? When she walks, she moves her ass so it makes a figure eight,” Ilya raised his hands and demonstrated what he meant.

“Oh yes, her buns are the best!” Yasha confirmed.

And we giggled. The brothers were older than Yura and me. Ilya was already fifteen. It wasn’t surprising that they weren’t indifferent to the spiciest details of Robert’s bride’s figure. It didn’t stir any emotions in Yura and me, but we couldn’t admit it.

“Alright, let’s go.” The elder brother interrupted this interesting conversation as he got down off the table. “Let’s go, or Robert will start yelling again.”

By evening, the yard was ready to receive guests.

Chapter 33. The Long-Awaited Day

“A few words about our newlyweds …”

Standing in front of the microphone so that everyone could see him, Uncle Misha summarized for the gathering the principal milestones in the lives of the newlyweds, Robert and Mariya. He spoke distinctly, emphasizing every word, no less skillfully than the leader of the music group who had spoken a moment before. His voice resounded over the tables placed all around the yard, up to Jack’s kennel. For tonight, Jack had been locked in the storage room.

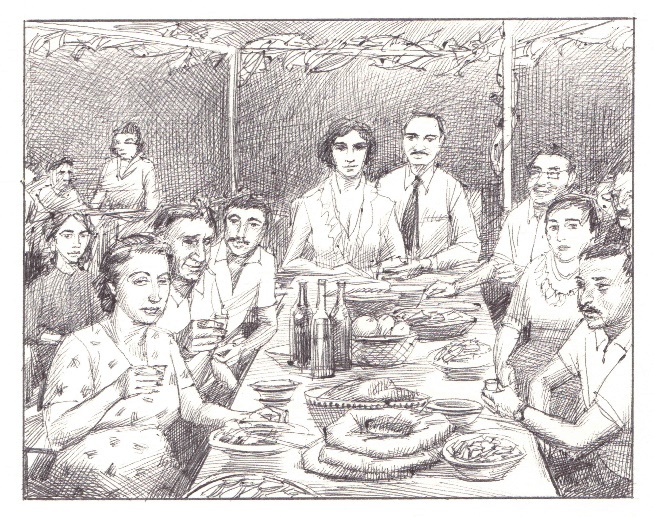

The light of many bulbs stretched above the tables illuminated the feasting guests. There were many of them, over one hundred people. It was so light in the yard that even the lush thick green crowns of the apricot and cherry trees glistened against the dark, velvety sky. The guests looked particularly well-dressed in that bright light. The tables set for the occasion with bottles, platters of appetizers and piles of vegetables were resplendent with abundance. They were about to start serving the hot dishes… Glass and porcelain sparkled, women’s dresses of many colors gleamed, laughter and voices droned on, sometimes even covering Uncle’s monologue. By that time, the guests had split into groups, small warm groups, each of which was having a good time in its own way. At the beginning of the event, everybody, as usual, paid special attention to the newlyweds, casting glances at them, sending them smiles and proposing toasts. But, after observing this decorum, the guests got busy with their glasses, plates, and conversations. They kind of forgot about the newlyweds, who sat in full view under the safe protection of their mothers. The guests would look at them from time to time when Uncle Misha’s voice became especially expressive or when he gestured toward Robert or Mariya with a sweep of his hand, as if calling upon the guests not to forget their duty.

Perhaps we boys were the most attentive listeners. If only Uncle Misha knew how we commented on almost every one of his phrases.

Our group, Yura, me, Ilya and Yasha, had made ourselves comfortable at the table near the apricot tree. We could see and hear everything from there. We could mock everyone and everything, our heads close together, to our hearts’ content. That was exactly what we were doing.

“After finishing eight grades, Robert entered technical school,” Uncle Misha informed the audience solemnly.

“Eight?” Ilya whispered, choking with laughter. “Yeah, a whole eight grades and playing hooky… or was it hockey?”

Satisfied with his quip, Ilya laughed loudly. Yasha poked him in the side, “Be quiet. There are people around… Let’s see what he says about Mariya. She must have just played hooky. He’d better tell us how she was ‘plucked’ today.”

Now we were all shaking with laughter.

Quite recently, as the guests were arriving, we peeked at the koshchinon right here, near the trestle bed. The word chino means “to pull out” in Tadjik. The koshchinon ceremony consists of plucking all excess hair from a bride’s face. It’s a very old Eastern tradition, but I’ve failed to discover its origin. As far as I know, it’s customary to do it before a wedding, setting apart a special evening when women of the bride’s and groom’s families get together. But with us, the ceremony took place in our yard shortly before the wedding celebration.

If the hair had been plucked with the usual cosmetic tweezers during koshchinon, there would have been nothing interesting about it. But the operation was done the old-fashioned way, with the help of an ordinary thread. They say that in the very old days, they used the thinnest leather lace to do it. A person who performed the procedure, called a koshchin, held a thread tied into a loop with both hands, between the spread thumb, middle and index fingers. Moving them fast, now bringing together the sides of the loop, now moving them apart, and running the thread over the face of the bride-sufferer, the koshchin skillfully pulled out all excess hair around the eyebrows, above the lips and on the cheeks, in a word, wherever it was necessary.

That was the ceremony we had witnessed under the apricot tree not so long ago.

Grandma’s friend Mira performed the role of koshchin. The principal person who was “plucked” was Mariya, but a few other women waited their turn, unwilling to waste such a rare opportunity.

Mariya was seated on a chair. Her head, wrapped in a scarf and tossed back, was held by one of the women. Aunt Mira sat down opposite her and spread her fingers. We could see the dark thread between her fingers perfectly well. The thread moved, its strands got close together, then drew apart, merged together like the jaws of a beast of prey, moving like a roller around Mariya’s face, which was getting redder and redder. Poor Mariya squinted, grimaced, even moaned, and Aunt Mira, repeating “You can take it, my dear” and rocking rhythmically, continued her work. It even seemed to us that we saw little wisps of hair between the parts of the thread.

“Ouch! She’ll pull out her nose!” I said to laughing Yura.

Mariya had a nice straight little nose located neatly on her small oblong face. She belonged to the category of girls who were attractive without make-up. With a short haircut, slender, neither stout nor skinny, with everything in moderation, she looked splendid in her white wedding dress. There was only one thing that evoked our malicious remarks, her gait. Mariya’s little bottom wiggled, forming figure eights when she walked, as Ilya had put it.

Meanwhile, Uncle Misha, after endowing the newlyweds with an incredible number of the best qualities, expressing hope for their future achievements, and wishing them happiness and wellbeing, finished his speech. He was replaced by a vocal-instrumental group that was quite popular in Tashkent – a doira, two guitars, a clarinet, and a singer. The group opened with an Uzbek song, one of the old favorites. The tanned singer with long dark hair performed it very well. She sang, taking dance steps and waving her raised arms. Her long silk dress dotted with roses danced as she moved her shoulders. Sparkling gold hoop earrings danced in her dark hair. That was when we forgot about teasing and gossiping and couldn’t tear our eyes away from the dark-complexioned singer. Our jaws dropped, and we sang along with her “Guli sangam, guli sangam…”

“The first dance is for the newlyweds! Please!” one of the guitarists announced, strumming his guitar. The guests applauded. Robert took Mariya’s hand and led her to the area in front of the tables. He usually stooped a bit, but today he stood up amazingly straight. With his hair neatly combed, he looked elegant in his new black suit. Mariya, in her snow-white gown, was cut out for the role of bride. In a word, they were quite a couple.

The newlyweds moved around the “dance floor,” smiling at each other tenderly. They danced well, feeling the rhythm and changes in tempo, their movements natural and supple. They didn’t stand close to each other but rather a bit apart. That’s how newlyweds should behave during the first dance in Central Asia. Those are unwritten rules, but they are strictly observed. Guests are not just spectators; they are very stern examiners. If a rule is not observed, an exam failed, so to speak, the gossip will travel all over Tashkent the next day.

The newlyweds exchanged tender glances and a few words. It was clear they were in love. Looking at them, I suddenly remembered the conversation I had accidentally overheard three months before the wedding.

I was playing in the yard, and Robert and his two older brothers were talking at the table near the cherry tree. I noticed them only when I heard Father’s loud angry voice:

“What do you need her for? Aren’t there enough other girls out there?”

Father was sitting with his back to me and I couldn’t see his face, but by the tone of his voice and the way he waved his hands it was clear that he was enraged. Misha patted him on the shoulder, trying to calm him down and, at the same time, saying something to Robert, trying to convince him of something. I couldn’t hear everything he was saying, only separate words “she… such… family” reached me.

I clearly understood that they were talking about Mariya and that the older brothers didn’t approve of her.

Robert listened to his brothers without saying anything, his head lowered. From time to time, he repeated, without looking at them and trying to seem calm, “That’s my choice. It’s none of your business.”

And now, after he had upheld his choice, Robert the Victor was dancing with his chosen one. There was joy etched on their serene faces. It would be ridiculous to expect that thoughts about what fate had in store for them would cross their minds at such a moment…

“Dear guests, join the newlyweds!” the leader of the music group announced. The guests came quickly to the dance floor. Charmed by the Asian music, they simply couldn’t stand still any longer. Things like that didn’t happen in our parts. There was no family celebration without traditional Asian dances.

The big area near the tables was filled with dancers. They moved over the ground in time to the music, moving their shoulders, their hands close to their faces, tapping their feet. From a distance, it looked like a multi-colored swaying carpet or a huge flower bed. The bright ethnic dresses made the women look like flowers, fairy-tale flowers that had come to life, dancing.

One’s hands were the most important part of this dance. They were like magic birds whose “flight” could be watched endlessly. Now their wrists turned gently from side to side, now they began to bend so rhythmically and gracefully that it sent a shiver of delight down my spine. It seemed that their hands were singing, that the music was emanating from them. Faster, faster, fingers were snapping… Suddenly, they came to a standstill, as if listening to the melodious tune… and then they resumed their bewitching dance…

In my opinion, to my taste, there is nothing more beautiful than an Asian dance. In Asian countries, including those of Central Asia, the culture of dancing, dancing skill, is not entertainment. It’s an emotional requirement, almost a necessity. The hand movements of almost any dancer, much less a professional dancer, are full of an expressiveness and grace that you rarely find in the best dancers from other countries of the world.

Young people, certainly, don’t mind dancing Western style, even when Asian music is played. And now, a few couples danced that way outside the circle.

“Who is Rosa dancing with?” Ilya asked with interest.

We all knew Rosa very well, but we weren’t familiar with her partner. He must have been invited by the bride’s family. We exchanged glances. It meant that Rosa had met this guy at the wedding, and he hadn’t hesitated to ask her to dance. On top of that, the couple chatted happily as they danced. Our customs hadn’t yet lost their patriarchal nature in those days. And such behavior seemed quite daring, even to us children.

“Just look at them,” Ilya muttered. “As if they’ve known each other for ages… Well, well, we’ll see what happens tomorrow.”

We giggled. We could guess what would happen tomorrow.

Tomorrow, the telephone would ring in Rosa’s house. One of the acquaintances who had been at the wedding would tell Rosa’s mother with an air of significance, “The kids looked so great together, really very nice!” Soon, another voice would sing on the receiver, “His family is so decent, a hardworking family… We used to work together.”

In a word, there would be many interested individuals ready to begin immediate matchmaking in absentia, who were absolutely sure that a dance at the wedding was sufficient reason to do so.

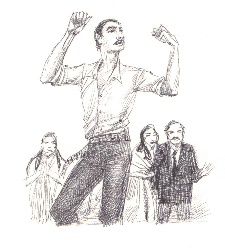

* * *Meanwhile, one of the dancers in the circle attracted everyone’s attention – he danced so jauntily and beautifully.

Here, he began to whirl in place like a leaf falling off a tree. His head was turned up, his arms pressed to his sides, with only his hands sticking out, which made him look like a penguin.

That’s how he went around the floor twice, and then he squatted half-way, beating the rhythm with his feet brought together, his arms outstretched in front of him, looking like a wrestler preparing for a fight.

Then he made another circle, snapping his fingers and rocking from side to side. His eyes half closed, he looked blissful, his lips moving a bit, singing along quietly – he was in the thrall of the music. If he had sorrows or grief, family problems – and who didn’t have them – he forgot about everything as he enjoyed that moment.

Yes, he was a wonderful dancer. That’s why everyone was watching him with such pleasure. The song was about to end, but the musicians understood that it would be a sin to interrupt such a dancer. It’s not good to interrupt a person who feels so happy.

So, the musicians began playing the song all over again.

Boop-p, boop-p. boop-p… The Uzbek doira, or drum, started its beat. The other musicians stopped playing. It was time for the drum solo, or rather a kind of competition between the dancer and the drummer.

The drummer set his instrument upright on the ground, held it between his legs and began to beat the rhythm, fast and with great force on the tightly drawn leather, with small rings attached to the inner part of the round surface of the drum. It seemed that the tightly drawn leather of the drum might snap under his tireless fingers, which were moving faster, making the sound even louder.

It was incredible! The drummer, flushed, his forehead covered with beads of sweat, bent over the drum.

Who would be the victor?

The dancer was tireless. He was spinning around the ground faster and faster, keeping up with the tempo of the drum, enchanting the viewers with new dance movements.

The drummer tossed back his sweat-covered head. His mouth was half-open. Another cascade of sounds… yet another … That’s it! He was exhausted… He nodded, and the other musicians joined in.

The dancer had won!

* * *They began serving the main course. Women were heading for the tables, one after another. They carried lagani, large, round, brightly painted platters piled with steaming pilaf.

The pilaf was arranged in tall heaps, and above them, curls of fragrant steam were rising, as if from a volcano. It was clear, and our noses smelled it, that today we would be having a real Uzbek pilaf, cooked with great skill. We began to salivate, just looking at it.

The long, dark rice mixed with amber, thinly sliced carrots and shiny black raisins looked like a mosaic. Fat, juicy pieces of lamb exuded heat.

Pilaf is a traditional dish in the countries of Central Asia, and in the East in general. It can be cooked in many different ways – with chicken, dried fruits, and even peas. But the most important thing is the skill of the cook.

Judging by the speed with which plates were emptied, the skill of today’s cooks was on a very high level, and the guests appreciated it.

I was devouring the pilaf when I suddenly heard a mournful yelp. It was Jack. I remembered that he was locked in the storage room. I began fishing out pieces of lamb from my plate. Jack would definitely have all the bones left after the wedding repast, but… I felt ashamed to be feasting without my friend. Besides, the pieces I had were tastier than bones.

More dishes arrived following the pilaf. This time, the women were bringing out chicken with fried potatoes.

The clatter of dishes, the clinking of glasses, laughter and the exclamations of the guests merged with the discordant but pleasant humming, interrupted by shouts of “Bitter!” (to make it sweeter, and the newlyweds are supposed to kiss), toasts and speeches.

The speakers were divided into two groups. The group representing the bride praised their “commodity” at the top of their lungs. The representatives of the groom praised his qualities with the same ardor. Both groups went out of their way, as if the wedding hadn’t yet happened and the question of the possible marriage was being decided right then and there.

* * *Dancing resumed.

I took advantage of that convenient moment, picked up the plate with the treats for Jack and made my way to the storage room. The door was latched, but its lower corner had come off the doorframe.

I squatted and saw something that reminded me of a big, shiny, black beetle close to the ground. That thing changed its shape, it had two holes that alternately narrowed and expanded. Snorting was heard. How come I didn’t understand right away that it was Jack’s nose?

I opened the door and, stepping into the storage room, closed it behind me. Jack whirled around me like crazy, pounced on me, put his paws on my chest, whirled again, telling me with his yelping how happy he was that I was visiting him. If Jack could have talked, he couldn’t have expressed it better.

Took-took-took! Jack’s tail drummed the door of the cabinet. Boom-boom-m! As Jack whirled, cans and boxes were scattered around.

At last, he calmed down a little, and I squatted and put the plate with food on the floor.

Before that, I had held it above my head and was surprised that Jack didn’t pay any attention to the tempting smells. But now, I could hear munching and crunching sounds. “Jack, my dear,” I whispered, stroking the dog.

I completely forgot that while Jack was eating, it was dangerous to approach him, and stroking him was out of the question. When approached, he would bare his teeth, snarling fiercely, ready to jump at you and bite you. It was different today…

Jack crunched some more and then grew silent. Two green eyes stared at me in the darkness. They were aglow and getting closer to my face. His moist nose touched my cheek, and something that was harder than the nose came up against it… Good heavens, it was a chicken bone.

Music was booming outside. They were having a good time, they were dancing. The long-awaited wedding was proceeding in full swing. But I didn’t feel like going back out there.

Something more important and joyful was happening in the dark shed. Friendship, great friendship had been born there. Not that we hadn’t been friends before – of course we were – but neither I nor Jack had ever given it a thought. We hadn’t known how to communicate it to each other, but we could today.

The most wonderful thing about it was that Jack was the first to do it.

Would I possibly be able to shoot a pit at him, to douse him with water, or hurt my friend in some other way again?

Chapter 34. Hammom

“Hey, Redhead, where are you?”

It’s amazing how the same words can sound when pronounced by different voices, with different intonations. My cousin Yura also shouts “Hey, Redhead!” Yet no matter how loud he does it, it always sounds brotherly and friendly.

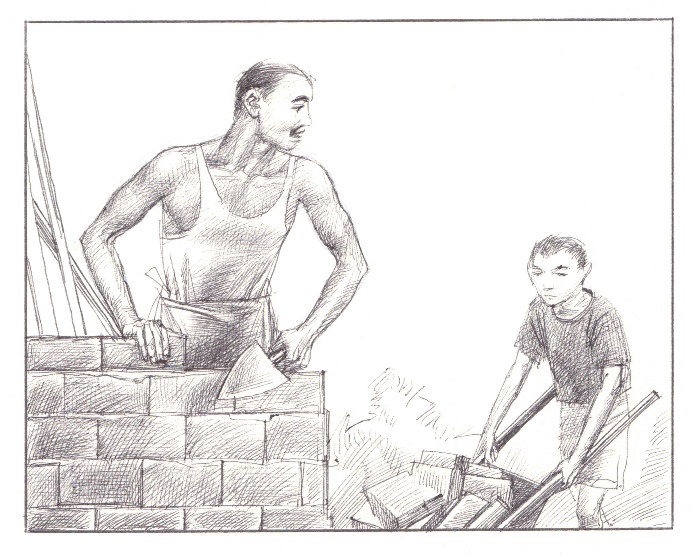

But this voice was demanding and rude, and I would call it unique. It was no wonder, the voice belonged to Uncle Robert… Uncle Robert, also know as Chief and Forelock, at this moment presented himself to me in yet another character which I immediately denoted with an exact, clear-cut word – “exploiter.”

I had heard that word at school many times. In the past, it had always been an abstraction for me. But now it acquired specific meaning and was filled with real content.

Uncle Robert had begun to build a hammom, or winter bathroom, and I was his only helper. My favorite cousin Yura was on vacation with his parents at the famous lake Issyk-Kul in Kirgizia. I was the only manpower Robert had available, and that was exactly what was happening now, to my great displeasure.

So, we were building a hammom. It was supposed to make the house more comfortable, compared to neighboring houses, which didn’t have winter baths.

In summer, like all our neighbors, we used the shower in the yard. Water was poured into the big yellow tank through a hose. It got so hot during the day that we had a shower with hot water. In winter, one had to go to the public bathhouse that Grandpa and Grandma had visited for many years.

An outing to the bathhouse was a real event for Grandpa Yoskhaim and would be planned in advance. On a bath day, Grandma put the appropriate clean underwear into Grandpa’s shoulder bag. Grandpa remembered to remind her that he would be home late because he also planned a visit to his barber. He had his own barber, for he didn’t entrust his head to just anyone who knew how to hold scissors.