Полная версия

Полная версияEverything Begins In Childhood

The participants in that show continued their ridiculous battle in the middle of the yard, ignoring the audience.

Perhaps, throughout our lifetime, the principal events that stick out in our minds are those that strike us with their unnaturalness and abnormality but at the same time are full of vivid details that spark our imagination. They include sounds, smells, scenes – instantaneous, like snapshots, feelings we experience – fear, pity, a realization of the ridiculousness of a scene that can hit us at the most tragic moments… And all that, blended together, remains in memory as a powerful and unforgettable impression.

That was how two seemingly incompatible scenes became intertwined, engraved in my memory. The first was the old yard at sunset: the intricate shadows of the trees, the wonderful aroma of flowers, the fresh smell of leaves after watering, the blissful tranquility, stillness and cool of the evening. And the other was the same yard, seized by madness: squealing, noise, shouts, faces contorted in fury, figures dashing around the yard.

One of them was my cousin Yura. He zigzagged among the trunks, disappearing under bushes and tables. Robert was destined not to catch up with him. He ran with all his might. Sometimes he seemed about to catch Yura, and then, waving the hose, Robert cried out a strange word, an expletive, perhaps formed of two words, “Su… Su-ka… Sukatina!” (Bi… Bi-tch… Bitch-itina) and tried to hit Yura.

But no, he couldn’t catch up with him, and the laughing Yura was already at the gate. Before disappearing behind the gate, he waved to his uncle with his fingers, which he held in front of his nose, his thumb pressed to its tip.

Panting, the enraged Robert yelled after him one last time:

“Bitchitina!”

The way he looked, it was good that he didn’t run out into the lane in pursuit of Yura. The poor fellow didn’t yet know that the strange swearword he had invented, “bitchitina," would become another of his nicknames.

Chapter 30. Kosher Chickens

The day that followed Yura’s unruly behavior was far from happy for him. The stricken groom, along with all the witnesses to the scandal, complained to Misha, Yura’s father, and Yura was given a good beating. Uncle Misha had a very heavy hand.

On top of that, the slighted party and his witnesses emphasized that it was Misha’s duty to bring up his son properly and that Yura must apologize to his uncle.

It was Aunt Tamara who was particularly indignant about her nephew’s behavior and demanded strict methods of upbringing. The whole family knew Tamara, a moralist who had neither the time nor desire to take care of her own children. They were raised by the street.

But this was not a question of Tamara’s children. In a word, Misha gave Yura an ultimatum – under pressure from the Yuabov family – and Yura had to make a public apology.

The ceremony was arranged with great solemnity. All the members of the family gathered in the yard: Grandma Lisa on the porch, Misha and Valya at their door, Robert, pointedly gloomy, on the trestle bed, and I on a chair not far from him.

Very attentive and with necks outstretched, we all watched “the protagonist of this drama,” who, shuffling his feet, crossed the yard toward Robert. Would he play another trick? I’m sure that was what each of us was thinking.

But Yura didn’t play any tricks this time. He knew how to control himself when necessary. On top of that, the apology ceremony fit well into the usual cat-and-mouse game he played with Uncle. He didn’t mind letting his uncle feel like a winner for a short period.

Pretending to be somewhat embarrassed, but leering at the same time, Yura came up to his uncle and mumbled something not quite comprehensible. “If you don’t bother me, I won’t bother you,” I thought I heard.

“Louder, so that everyone can hear!” Misha demanded.

“Chief, forgive me, all right?” my cousin said loudly.

Robert’s gloomy face brightened up. He smiled like a warrior who had managed to gain the upper hand in tough hand-to-hand combat. Winning an apology from Yura was an unprecedented feat.

As soon as that moralizing ceremony was over, the adults resumed preparations for the wedding.

A few relatives arrived to help with the cooking. A kaivonu, a cook who specializes in serving family celebrations involving many guests, stopped by. Somebody had already gone to the market to carry out the difficult task of buying and delivering the great quantities of groceries.

However, Grandma Lisa, to maintain her reputation as a good hostess, had decided to add her own poultry to the store-bought provisions. It should be mentioned that on that day Grandma Lisa was kinder and merrier than usual. Preparations for the wedding, the general bustle, the presence of outsiders – all that livened her up. She felt she was the head of a big family, and that definitely enhanced her feeling of her own importance. Standing near the henhouse, Grandma called to Yura and me cheerfully:

“Valery, Yura, bring the baby carriage. It’s near the pantry. Hurry up! Hurry up!”

The old baby carriage, its big wheels large enough to accommodate twins, used to be Yura’s. Now, it served as a cart. We rolled it to the henhouse and were given another assignment.

“Let’s catch five hens. No, four hens and a rooster. Take them to the synagogue to get their throats cut. Yura, do you remember how to get to the synagogue?”

Sure, Yura remembered. A trip to the synagogue with chickens sounded like a pleasant entertainment to him. Unlike me, he was glad to take on the task of catching the chickens. I felt disgusted. I was sorry for the snow-white cacklers, my interlocutors. Yura entered the henhouse alone. Some excited, cackling chickens were caught, one after another, and we helped Grandma tie up their legs and put them in the carriage.

It took forty minutes to walk to the synagogue. From Korotky Lane we reached Severnaya Street and, from there, Shpilkov Street. It was wide and shady, like Shedovaya Street.

There were a few stores there, as well as the Museum of Applied Arts, famous throughout the republic, where amazingly beautiful jewelry, embossed design products, embroidery, carpets and other works by old and new Uzbek craftsmen were exhibited. An Intourist bus was parked in front of the museum. Foreign tourists were brought here all the time; a visit to the museum forming a part of many a tourist’s itinerary. That’s why there were always kids around the museum entrance, shamelessly trying to coax chewing gum and souvenirs out of foreign visitors. “Please, gum! You have gum?” These English words were familiar to school and kindergarten children.

However, the police often drove the kids away, for it was assumed that foreigners would take pictures of boys with outstretched hands and then publish them in the West: “Soviet boys beg!”

The baby carriage was swaying smoothly. The big wheels creaked slightly. The chickens, almost lulled to sleep, mumbled something mournful: Pok, pok, Po-o-ok. Noon, with its heat, had arrived. Even though the hood of the carriage was up, protecting our prisoners from the sun’s rays, the chickens were hot and ill at ease. They lay with their beaks open, revealing their small, straight, bright-red tongues.

Passersby probably thought that we were two caring siblings pushing a baby carriage containing our brother or sister. It actually looked like that if you didn’t listen closely to the sounds coming from the carriage. They were babies all right, just not swaddled. And, by the way, it would be necessary to clean the carriage thoroughly later.

We walked, chuckling and chatting, and Yura had just begun to tell me about the wonderful knives for sale at the hardware store nearby when everything went head over heels.

The rooster began emitting strange shrill sounds, flapped his wings and shot up, hit the roof of the carriage, then fell on top of the hens, shot up again and flew out of the carriage. He came tumbling down onto the asphalt and began hopping around on his bound-up legs, flapping his wings violently, and then fell into a dry arik. Right after that, the white hens began flying out of the carriage, cackling frightfully, flapping their wings and losing feathers.

The noise was terrible. The carriage was shaking and rocking in all directions. It seemed to be ruled by a mystical force. Feathers floated around like snowflakes. We didn’t even have time to get scared. We simply froze. I came to my senses when the last hen, which flew higher than the others, rushed past my face and – pakh-pakh – swatted me twice in the face with its wings.

Curious passersby began to gather around us, some of them laughing, others giving advice.

At that point, Yura and I came to our senses.

“Catch them! First the rooster!” Yura yelled.

We began to steal up to the fugitive from two sides down in the dry clay arik, trying not to scare him away. But the rooster didn’t have escape on his mind. On the contrary, he was eager for a fight. With tattered wings and tied-up legs, he still looked like an enraged eagle. Hopping up, he scratched the earth with his claws, which were sharp as knives. His eyes sparkled, the beak on his head with its outstretched neck was ready to inflict blows.

I stopped. The rooster and I were looking at each other intently when I saw Yura closing in on him from the other side of the arik, his arms outstretched.

At that moment, the rooster lunged at me. Wild sounds reminiscent of a crow cawing issued from his mighty beak. He was coming at me at very high speed, hopping springily. He seemed like the devil incarnate to me, like a monstrous, fantastic one-eyed bird, ready to kill me.

I was a very fast runner, and now, the wind hissed in my ears, my body felt weightless but, at the same time, acquired unusual sensitivity. It seemed to me that the rooster’s beak was about to pierce my lean bottom… or my spine… and break through it. I would fall down, and the enraged bird would press me to the ground with its mighty claws and begin tearing me apart.

Yes, that escape attempt was a moment of truth sent to me deliberately by fate. I turned from butcher to prey for a short time, the same sort of prey the rooster had been in our hands.

I stopped upon hearing Yura’s voice. The rooster was no longer chasing me. Yura had grabbed it by a leg, though it dangled in the air, all the while trying to break away, flapping its wings and wailing.

“Redhead, over here!” my cousin yelled. “Hurry! Let’s tie it to the carriage!”

As soon as the rooster was in Yura’s hands, I recovered my courage. I dashed to the carriage and found a shoelace on the bottom. We tied the poor rooster, whom I hated bitterly at that moment, to the frame. Dealing with the hens wasn’t a problem, for they were thrashing around not far from the carriage, to everyone’s amusement. The unfortunate inhabitants of the henhouse were so tired from their unsuccessful escape attempt that they didn’t cause any more trouble for the rest of the way. But we continued to grumble for a long time, cursing our captives and threatening the vicious rooster with his upcoming inevitable execution.

The synagogue was located in a small two-story, U-shaped private house.

The yard, formed by the house and its outbuildings, was paved with bricks and stone slabs. There was a long green awning attached to the roofs on three sides of the yard. There were tables and chairs under it.

The light that came through the awning tinted the walls of the house and the yard a pleasant turquoise color, soothing to the eyes. It was very cozy there. Perhaps it seemed to people who prayed in the shade of the awning that they were actually under the protection and auspices of the One to whom they appealed with hope. There were a few synagogues in Tashkent, but that was not enough, and worshipers usually suffered from crowded conditions. Grandpa attended that very synagogue to which we had come, and he often grumbled that there was no room to stand and no seats to sit on. But on that weekday the synagogue was empty.

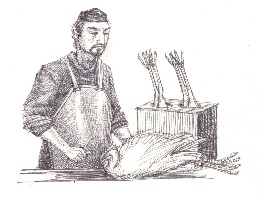

An elderly man with a beard and bright skull cap, which Bukharan Jews wore instead of kippahs, appeared upon hearing the squeak of the door. He was the synagogue’s shochet. After asking us what we had come for, he nodded and came out to the yard.

It is well known that the Torah doesn’t allow Jews to eat all meat and fish products, but even the permitted ones must be prepared in a special way, and only an expert, a shochet, can butcher animals and poultry. He must butcher them in a particular way so that all the blood drains from them, because the use of blood is forbidden by the Torah.

If we consider the numerous holidays, family celebrations, birthdays, bar mitzvahs and weddings, it’s not difficult to imagine how much work a shochet has.

“Which one shall we begin with?” the shochet asked, looking into the carriage.

Neither Yura nor I answered him. Our grudge with the rooster and our thirst for revenge had left us. We stood silently in front of the carriage. We didn’t look at the chickens. We looked at a strange structure in the yard, close to the exit. It was quite tall and made of wood. There were cone-shaped chutes sticking out of it. On one of them was a straight razor with clotted blood and chicken fluff on its blade. I couldn’t turn my eyes away from that razor once I had caught sight of it.

The chickens were silent and didn’t even stir in the carriage.

The shochet didn’t ask us any more questions. He took one of the hens by the wings, pulled them back and slashed its throat with the razor. Blood spurted out in a scarlet jet. The hen started, as if an electric current had run through it, its legs shook convulsively, and it fluttered, trying to break away. Its eyes and beak were wide open, and the yard resounded with its hoarse screeching.

That terrible screech pierced Yura and me like an electric shock, but the shochet’s hand didn’t shake. Holding the hen firmly, as if gripping it in a vise, he lowered its head down into the chute, and in a few moments all life had left its body, along with its blood.

The carriage was soon empty. Five pairs of legs, their claws spread apart, stuck out of the five chutes. The shochet then placed the chickens into the carriage. We paid him and left.

Kirk-kirk – the wheels squeaked slightly, as before. The carriage rocked gently. Its bottom was covered with a fluffy white mat of chicken bodies, speckled with blood here and there.

The chickens looked as if they were asleep. We walked without talking, as if we were afraid to wake them.

The hot air still hung over the city.

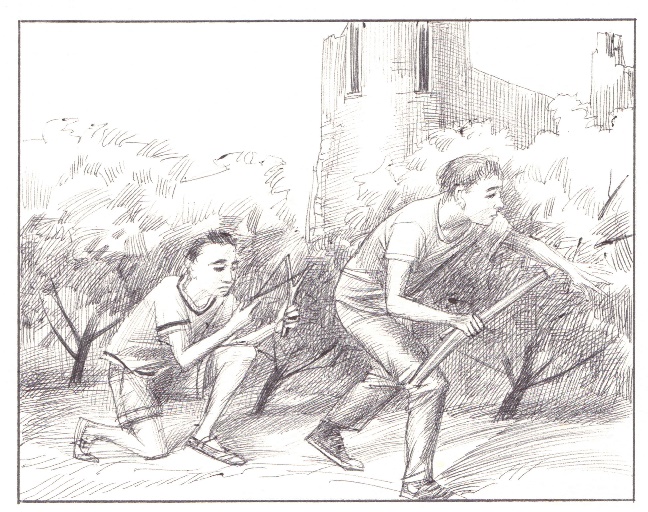

Chapter 31. The Battle Near the Old Fortress

There are, most likely, no boys in the world for whom the notion “a useless thing” exists. Boys have their own ideas, scale of values, and needs. A bent nail thrown out by someone can be either an excellent piece for a slingshot or a fishhook. An empty shampoo bottle can be turned into a spray bottle – you just need to make a hole in the lid. Cherry pits can serve as excellent bullets for a sawed-off shotgun handmade out of all sorts of “useless things.” That was what we were busy with that morning.

I had just parted with Grandpa, who had gone to work, when Yura, still sleepy and disheveled, yet businesslike and anxious, darted out into the yard.

That evening, we were supposed to take part in a battle, a big battle near the Old Fortress behind the CentCom building. And our arms, those very sawed-off shotguns, were not ready. We had no time to lose.

We started with some cherry pits, which I had had the foresight to save from the preserve making: bullets always came in handy. I had kept them in a paper bag, so they were somewhat damp with bits of pulp stuck to some of them. We spread the cherry pits on the table near the trestle bed so they could dry out in the sun. Bullets had to be very dry.

Now, we could get busy on our weapons.

A wooden barrel, approximately twenty centimeters long formed the base of a shotgun. A clothespin could be attached to the front end of the wooden barrel. An elastic band from lingerie or, even better, a rubber band like they used in stores for packing, could be nailed to each side of the rear end. A pit, or rather bullet, was placed in the rubber band just as in a slingshot. But that was its only similarity to a slingshot.

A shotgun was more complex to use. The rubber band with the pit had to be pulled back cautiously and clutched in the clothespin. Then, you took aim, pressed the clothespin, and … b-b-bang! In a word, our shotgun could shoot almost like a real gun. One only needed to make it properly, so that the rubber band held firm and the clothespin didn’t move.

It was easy to find pieces of wood for the barrels in the pile of scraps near the summer shower. Then, we needed nails, and not just any nails, but a certain size. We knew perfectly well where to find them. We just needed to figure out how to get to them.

Nails, large and small, and special shoemaker’s nails were kept in Grandpa’s storage room in the yard, not far from the lavatory. We weren’t allowed to enter it. Yura, of course, had done so without permission more than once, more than twice. Since I was a visitor, I had entered the storage room with Grandpa in the past. We needed to sneak into the storage room quickly and remain unnoticed, but we couldn’t figure out how, for the storage room door was terribly squeaky.

“Last time I opened it, Jack was barking,” Yura remembered. “Let’s tease Jack.”

We jumped around Jack, making faces, but he lay calmly, glancing at us lazily from time to time. Perhaps he was thinking, “Who knows what you want?… Now don’t bark… Now bark suddenly…”

Yura picked up some small pebbles and began throwing them at Jack. One of the pebbles hit the kennel. Jack couldn’t take it any longer, jumped up and burst into loud deep barking. I wasted no time and darted into the storage room, leaving the door ajar.

The rays of light that penetrated the storage room through the crack lit the dark little shed with its low ceiling and earthen floor. The old cabinet was on the wall across from the door. It seemed to be looking sullenly at us, not expecting anything good from these uninvited visitors. It was a very old, unvarnished cabinet without a single scratch. Perhaps the darkness that always surrounded it protected it well.

Yura held back the door so that it wouldn’t squeak, and I flung open the door of the cabinet. What couldn’t you find in there! Everything you would need for starting a shoe factory right in our yard.

Rolled strips of leather that looked like scrolls of ancient parchment were on the upper shelves. They gave off a pleasant smell. The lower shelves were filled with paper bags full of heels, soles, taps, laces, and other small items used in shoe repair.

“Hurry up, you’re so slow! Look on the lower shelf!” My cousin pushed me.

But when I got to the bag of nails, I couldn’t find the ones we needed right away. Nails, like hedgehog’s quills, pricked all my fingers, and I moaned and yelped slightly while Yura hopped up and down impatiently at the door.

At last, the nails were in my pocket, but I didn’t feel like leaving this very interesting little shed. It was filled with boxes of old household utensils – kettles, basins, a beautiful copper pitcher with a long, thin, swan-like neck and a decorative lid. There were many other wonderful things there. “Oh, look,” we whispered, rummaging through boxes. Yura had propped the door open with a brick and joined me in this absorbing pastime. We felt like treasure hunters about to find a box of gold coins, a Damascus steel saber or at least an old pistol. Our finds were much more modest, of course, but a roll of insulation wire wasn’t a bad find. We could use it when we make slingshots.

We managed to make our sawed-off shotguns quite quickly. Now we needed to test them, and to practice.

The yard offered many targets. We could shoot at leaves or an old bucket near the duval, but we preferred a live, moving target, like Jack, for instance. At that moment, he was sniffing at something near his kennel.

That sniffing, it should be mentioned, wasn’t a random occupation or the result of finding something whose smell attracted Jack. No, it was a part of the special canine ritual Jack performed after he woke up. Since Jack took quite a few naps throughout the day, we witnessed the ritual often.

After waking up, he would sit with his rear paws wide apart and lick his groin and stomach clean. Jack was cleanly, and he did it without haste, conscientiously. Then, he would begin to stretch with great force until he turned into a kind of arrow. His fur, pressed to his body, became smooth and shiny. Even the tip of his shaggy tail became smooth. And what true delight his snout expressed! Jack’s ears were pressed to his head, he would squint blissfully, and he had a broad smile – there’s no other way to express what would happen to his snout.

No matter how many times I watched Jack stretching, it always seemed to me that he could stretch endlessly. If I tied his hind paws to something and stepped away from him with a tasty morsel in my hands, sausage, for example, Jack would begin to move his front paws as he advanced forward. One meter, two, three… he would move closer to me, and his body would stretch and stretch, becoming a thin tape about to break… Then I, of course, wouldn’t be able to resist any longer and would give him the sausage.

So far, I had performed such experiments only in my mind. And Jack, after stretching safely to his heart’s content, proceeded to sniffing. I think he was performing a test, and a thorough one at that, to see if everything was all right throughout the territory that belonged to him, Jack. Had anything unexpected happened there while he had been asleep? Had a treacherous, camouflaged enemy invaded his area? Had it been mined, to put it in military terms.

As far as I know, this is an ancient custom of dogs, inherited from their wild ancestors, just like the invariable rule of marking the border of their property by irrigating it… Taking into account Jack’s fellow yard dwellers, that rule was not superfluous. It took no effort on Yura’s part to sneak up on the poor dog while he was asleep and attach an empty tin can to his tail or play some other mean trick. It wasn’t Jack’s fault that Yura didn’t understand about his “marking” and didn’t obey “the laws of the jungle.”

Usually, when Jack inspected his property, he didn’t discover anything alarming. He may now and then have come across harmless border violators, ants or beetles. They were harmless all right, but they had to be punished. Jack did that with great pleasure. Bringing about the demise of a poor ant was a joyful, absorbing game for Jack. With his front legs bent and his chest near the ground, he would stand motionless, wagging his raised tail, then jump up and begin to frolic. That was something! It was a real dance. Even as Jack danced around his prey, he didn’t look blood thirsty. On the contrary, his snout would express sheer childlike joy. Jack would lean over an intruder and begin to sniff it, snorting and yelping slightly. His moist black nose twitched in all directions, his nostrils would expand and contract. Then he would put his nose down close to the insect, his eyes cocked… Woooop! His red tongue flashed at incredibly high speed, and the ant was gone. Sometimes, Jack, as a change of pace, would press some poor little thing into the ground.

* * *As we searched for a target, Jack froze near his kennel, his tail erect, sniffing a beetle or ant. His beautiful fluffy tail was a perfect target. Yura was the first to shoot; I followed. The dog continued enjoying himself. We had missed! The second shot was successful. Jack jumped up, made himself comfortable and began chewing on his tail. Perhaps he thought he had been bitten by a flea.

We decided that Jack had had enough, and we switched to more complex moving targets: flies and gnats. It was great to shoot at gnats as they swarmed, a dense cloud in the air. When we shot at such a cloud, we could see how the “bullet” cut across it. The cherry pits hit the leaves on the trees and the walls of the outbuildings. The hissing of bullets and their clicking, so pleasant to a boy’s ear, filled the yard for several hours. We practiced to our hearts’ content.