Полная версия

Полная версияEverything Begins In Childhood

It was time to go to the tower. We requested permission to go – we didn’t want to take off without it this time – and left the yard.

* * *The heat was subsiding. The intensity of the sultry, desert-like air was lessening. It was growing milder, cooling off gradually. It was the asphalt that still emitted waves of hot air, releasing the daytime heat. Metal roofs, made red hot during the day, were now shrinking and “firing occasional shots” as if complaining about the trials they endured. Birds began to wake up after their day’s rest in secluded corners – sparrows were chirping, doves cooing.

Korotky Lane, where we lived, was a third of a kilometer long, matching its name: “short.” It was shaped like a “T,” and three streets bounded the lane. Shelkovichnaya (Mulberry) and Severnaya (Northern) Streets could be seen to the left and right of our gate, and Herman Lopatin Street, formerly Shedovaya Street, was at the end, at the bottom of the T. That’s where we headed, stopping on the way to pick up our friend Kamil.

Kamil, who was my age but tall beyond his years, was a calm, modest, quiet boy. He never bragged, though he had reason to.

His yard looked like ours but a bit smaller and impeccably clean. It was a typical Uzbek yard, cozy and inviting.

On the path leading from the gate to the house and into the garden there was a big trestle bed covered with padded blankets. Every time I visited Kamil, his grandpa and grandma would welcome me like an esteemed guest. The old man would take me to the trestle bed, tapping his walking stick, sit me down and begin to ask about my parents and the way we lived in the new town. And Grandma would come to the trestle bed bringing bowls filled with fragrant tea. I felt awkward and embarrassed.

I would try to sneak away and play with Kamil, but Grandpa and Grandma followed the old customs strictly. Besides, they must have missed the company. And I always had my tea along with many stories that were so interesting that I no longer wanted to leave. I sometimes spent hours on the trestle bed with the old folks and Kamil, listening, now about the basmachs (members of an anti-Soviet movement) during the civil war, now about earthquakes, then about Timur, the awesome conqueror.

That beautiful, hospitable yard was also amazingly quiet. No one yelled or argued here. Grandpa and Grandma talked to each other respectfully and affectionately. I was sometimes surprised – how could they have lived together for so many years and not grown tired of each other? And I remembered my grandpa and grandma… I thought that was the reason Kamil had grown up to be so calm and sympathetic.

By the way, his uncle was also like that. That short potbellied man was very popular among the local boys. Uncle Sayid had a rifle. Well, it was an air rifle loaded with little pellets. Uncle Sayid allowed his nephew’s friends to use that rifle, when he was around, naturally. And he acted as a shooting instructor.

“Press it… harder, close to your shoulder,” he would say, standing next to me. The heavy rifle in my weak hands would sag and I couldn’t aim properly. The patient teacher levelled the rifle as he continued to instruct me.

“Good. Well done. Close your left eye. Do you see the target? Freeze.”

“Freeze,” I thought, desperately fighting the force that kept pulling the rifle down. “I can’t freeze, I can’t…”

“Don’t breathe, and press the hammer smoothly,” I heard him command.

I squinted and pressed the hammer. A shot was heard… Missed!

“It’s all right,” Uncle Sayid said calmly. “We’ll try one more time.” The barrel was opened, the shotgun loaded. The lesson continued…

* * *This time we didn’t have tea with his hospitable grandparents. Kamil was ready and armed, so we set out for the Fortress.

When we reached the CentCom building, we remembered the rumor that all the old houses on our streets would be torn down, and multi-story buildings made of prefab units, similar to the CentCom building, which was considered the acme of modern urban development, would be erected instead. Perhaps the city authorities liked the idea, but we couldn’t even imagine such a thing. Who would voluntarily exchange their own adobe house, perhaps without all the modern conveniences but with fruit and vegetable gardens, small barns with various kinds of livestock, chickens, sheep, goats, and yard dogs, for the comfort of tiny apartments devoid of all the joys of unrestricted living?

Even at our place in Chirchik, it was better. At least, we had verandas and vegetable gardens.

“Well, if they tear down the private houses, we won’t have a choice. They’ll make us move,” prudent Kamil said.

We reached the grove where the Fortress, or rather its ruins, was located. Only the cylindrical brick tower with its narrow embrasures, or openings, had survived and was in rather good shape. It wasn’t too tall, just three stories high, but it still towered over the treetops. A bit farther away, the tall beautiful gate remained. It was made of bricks, crowned on both sides with turrets and an ornate pediment over its center arch.

Kamil’s uncle had told us about the Fortress. It was built in the second half of the nineteenth century between the former Shedovaya Street and the Anhor embankment. It was a real defensive fortress with thick walls, the embrasures, the corner bastion and tall ramparts around it. It protected the whole city. In former times, a cannon shot was fired every day at noon.

There were many buildings inside the Fortress – barracks, officers’ quarters, a powder magazine, and an infirmary.

Uncle Sayid told us, and he had heard it from old people, that at the beginning of our century, there had already been unrest in the Fortress. Soldiers of the Tashkent garrison, quartered in the Fortress, rioted and staged a real uprising during the 1905 revolution. There was also fighting here during the civil war. I don’t know whether the Fortress was ruined at that time or later. It was a pity. But Tashkent residents continued to call the romantic ruins “the Fortress,” just as it had been called in the past. And, of course, it attracted all the boys in the neighborhood – what could possibly be a better place for battles? There was still a grove near the Fortress; it wasn’t big, but it was dense. Perhaps there had been a big park here at one time, but it had gradually been chopped down, particularly when the CentCom building was under construction. Still, many old trees with thick trunks and wide crowns survived. Oaks, poplars, maple trees, chinaras (Eastern plane trees), and acacias stood, along with winter apple, cherry, apricot and mulberry trees.

That was where we were headed.

* * *On this occasion, there were about ten boys at the Fortress, everyone we knew from the neighboring streets. Each one arrived with a weapon; some of them had slingshots besides their sawed-off shotguns. This battle was not going to be a laughing matter.

“You’ve got quite a shotgun… It’s first-class!” Sasha said to Kamil. He and his brother Slava lived across the street from us. “Even the barrel is polished.” Kamil gave Sasha his shotgun, and Sasha took aim with the air of an expert.

“My uncle helped me make it,” our friend answered timidly, flushing from the praise. “We polished it to remove any splinters.”

Kamil had reason to be proud; the shotgun was splendid. And it had a rubber band from the store, not one taken from underpants.

“Well, shall we begin?” Kamil said. “Is everyone here?”

Kamil, even though he wasn’t a braggart or a show-off, was usually our leader. It just seemed natural to choose him.

“Don’t shoot at anyone’s head,” Kamil warned us.

“Or at their balls,” someone cried out.

Laughter rang out.

“And slingshots don’t count.”

After everybody had expressed their opinions, we divided into two groups. The terms of the battle were simple – one group had to withdraw beyond the edge of the grove to give their opponents time to hide, and then they would begin their offensive by sneaking up on the hidden group.

The goal was to destroy as many enemy soldiers as possible. Everything counted – bumps, bruises and, during the battle itself, any “ahs,” “ouches” or other evidence of direct hits.

The winner would be determined after the battle, when the casualties were counted. Of course, that’s when arguments would arise, and it wasn’t always possible to determine the truth.

Now, we needed to decide which group would stay near the tower and which would go on the offensive. We did it by coin toss, which was our substitute for the medieval warriors’ custom of having a duel between two bogatirs (Russian epic heroes) to determine which army would begin the offensive.

Our bogatirs, Kamil and Ahmad, who was as tall as Kamil, with dark hair and a weather-bitten face, stepped forward for the coin toss.

A coin shone in Kamil’s hand.

“Which do you choose?” he asked Ahmad. “Heads or tails?”

“Heads,” Ahmad answered.

It was assumed that the winning side would stay at the tower. It was easier and more advantageous to defend than to sneak up on the enemy.

Another of Kamil’s abilities was tossing a coin as skillfully as a juggler in the circus. He could toss a five-kopek coin so that, after flying high in the air, it would land on a table on its edge and spin for a long time, like a top, in one spot.

The coin flew straight and high. Kamil caught it, slamming it onto the back of his hand.

“Tails,” our leader stated calmly, showing Ahmad and the rest of us the coin on his hand. “All right, after you leave the grove, count to one hundred and… Forward!”

“Hide! Camouflage!” Sergey, a boy from the CentCom building, said. “We’ll win for sure.”

Sergey would always get angry about all sorts of trivial things.

We deliberated on how to hide while Ahmad was taking his army away.

“It would be great to climb up there,” Sasha said looking at the tower. “Why did they have to board up the door?”

“Why… why… Of course, they store arms there,” Slava, Sasha’s elder brother said. “Otherwise, they would have turned it into a museum long ago, wouldn’t they? It’s a relic from the past. Why board it up?”

We were naïve, and we couldn’t imagine how many ancient churches, monasteries, mosques, and other wonderful relics of the past had perished all over the country, how many of them had been neglected, destroyed, boarded up, turned into warehouses for gasoline or storage for potatoes…

We stared at the tower thinking about the wonderful arms that might be hidden there.

“A Mauser cartridge holds twenty-five bullets,” I sighed. “You can shoot and shoot, and you’ll still have lots of them left.”

“A Mauser is heavy. A Luger is a different story. I saw one at the museum. That’s quite something. It’s light, and they say it’s not loud…” Slava began his story. But Kamil interrupted him, “Enough about Mausers, guys. Load your shotguns. Take your places. Hurry up, hurry up!”

It was really time to get ready. We could hear from the distance, “Ninety-five…” as we were splitting, camouflaging and hiding behind the wall of the tower.

I squatted with one knee pressed against the ground behind an oak. Not far from me, Kamil and Yura puttered about in the crown of a tree, settling in the branches. It grew very quiet. My finger was tensed, holding the clothespin. A cherry pit couldn’t wait to fly out.

I scrutinized the thick green foliage, trunks and branches till my eyes hurt. It seemed that someone was to my right… Branches stirred. A figure dashed to the next tree but failed to hide.

“Ouch, ouch! My head!” The runner yelled. “You’re not allowed to shoot at the head!”

But it wasn’t just his head, he was also holding his knee. It meant he was out of the game.

Yura’s laughter was heard from the tree. A pit hit the bark of my oak, and another. I had come under fire. I bent down and ran to the nearest thick tree trunk, reloading my shotgun on the run.

As I made myself comfortable, something hit me on the head and fell to my feet… It was a green apricot. I looked up and saw Yura’s laughing face among the branches of the apricot tree. He was a person who could have fun under any circumstances. I shook my fist at him.

“Look behind you,” Kamil’s restrained whisper was heard. Just in the nick of time. I looked over my shoulder. Ahmad was aiming as he ran toward me. He had managed to come up from behind us.

Everything that happened after that occurred at incredible speed. Something happened to my eyesight. It seemed to me that it wasn’t Ahmad but rather our beloved Uncle Robert, running with a piece of hose in his hands. Ahmad’s face was distorted with the same absurd fury that had distorted our uncle’s face as he chased Yura. The only thing that was missing was Robert’s moustache.

Three shots rang out in quick succession. A pit whistled by my ear, hit the trunk and ricocheted into the back of my head.

Yura’s and my shots turned out to be more successful – the enemy leader was wounded twice. I saw him bend down, hold his stomach and curse. Well, two cherry pits weren’t just a flick on the nose.

I didn’t manage to enjoy my achievement for very long. I felt a sting on my hand, groaned and dropped the shotgun, so unexpected was it. The battle was over for me.

“Valery, how are you?” Yura yelled, his voice anxious.

I had no time to answer. Someone started shooting at the apricot tree, perhaps not even seeing Yura but shooting at the spot from which his voice emanated. He fell out of the tree like a ripe fruit and began hopping on one leg in a strange pose – he held his stomach with one hand and his bottom with another. One would have thought that an enemy’s bullet went right through him.

Actually, as we later learned, a pit had cut into Yura’s tender bottom with such force that Yura pulled his trigger accidentally. His own bullet hit a branch with such force that it ricocheted treacherously into his belly.

After jumping up and down, Yura maliciously cursed his absolutely innocent shotgun, which was lying under the tree, and hurled it against the brick wall of the tower with all his might.

Fortunately, Yura’s and my “deaths” didn’t do the enemy any good. While they were shooting at us, Kamil, Slava and Sasha defeated them completely.

The survivors triumphed. The defeated gradually returned to their senses.

“So, Sergey, who defeated whom?” Slava asked proudly.

“Next time…” a gloomy Sergey promised.

I don’t remember why, but the next time never arrived.

That was a pity. The tower, at least, must have missed our childish combats, echoes of previous real battles…

Chapter 32. A Wedding Is a Serious Affair

If you examine the way people prepare for an event, it’s usually possible to determine their attitude toward that event and the significance they attach to it, particularly if it’s a traditional kind of event. Families of Bucharan Jews do their utmost not to be worse than others in such cases, though this is probably not only true of Bucharan Jews. It may be the attitude toward such customs all over the world.

The preparations for Robert’s wedding, which had been going on for many days, assumed frightening proportions by the end.

The house, along with the yard, looked like an anthill. There was cleaning, washing, chopping, frying, steaming, nailing things down, fixing, painting from morning till night, day after day, but, as Grandma Lisa put it, “there is no end of work to be done.” She, however, supervised the whole thing with enthusiasm. Her voice could be heard all the time, valuable instructions flying to right and left. She gave assignments to the professional cook, to all the women who had arrived to help, as well as to the members of her own family.

“There’s not enough salt… Add some water, it’ll boil down… How come you haven’t cut it yet? Hurry up, hurry up, it’s time to add it… Take it to the yard… Get it from the fridge… No, another one!” Those and similar commands sounded without a break, giving Grandma’s “team” no chance to relax.

She was so busy that she forgot all about her “spondulosis,” up until a certain moment. By evening, after she served supper to Grandpa upon his return from work, Grandma found it necessary to end the day with her special ceremony.

The kitchen door was thrown open with a bang. Grandma appeared in the doorway, her face a picture of suffering. She walked slowly, swaying, shuffling her slippers, her arms spread as if she were afraid of falling down.

“Valery, bachim…” Grandma’s voice was heard. It was a barely audible voice, filled with unusual tenderness, the voice of a very tired person ready to inform her relatives that she was about to part from them for good. “Valery, bachim, after Grandpa eats, take the dishes to the sink. I can’t do it. I’m so tired.”

Grandma crossed the room slowly, swaying more than before, losing the last of her energy, and reaching the television just as The Latest News broadcast began.

Grandpa Yoskhaim was having supper at the table across from the TV. I usually sat on the couch next to him for the reason I will explain. He took Grandma’s “ceremonial march” as an annoying interference – she blocked the screen.

“Pass, Lisa, pass faster,” he said impatiently, paying no attention to Grandma’s hints of tragedy.

The thing was that The Latest News, foreign news in particular, was the only program Grandpa watched and considered worthwhile.

“They show all kinds of crap,” he would often comment indignantly when he stopped for a minute or two by the TV and saw me watching a movie or something else. “Why are you watching that? You should switch to the news.” As soon as the news began, Grandpa forgot about supper. He froze, spoon in hand, halfway to his mouth, stopped chewing and held his ear with his other hand. Alas, it didn’t always help, for Grandpa’s hearing wasn’t good. That’s why one of his grandsons, either Yura or I, had to sit next to him at that important moment to narrate the news.

I was the narrator on duty during my vacations.

“Well? What? What’s he saying?” Grandpa asked all the time.

He pushed me, keeping me from hearing the news properly, and, after my muddled narration, he often argued with me, was indignant and offered his own interpretation. Grandpa assumed that he knew everything that was going on in the world better than “those fools.” He became particularly agitated when something about Israel was broadcast. That’s what he was waiting for as he watched The Latest News. As soon as “Israel” was heard from the television, and more often “Israeli militarists,” Grandpa wouldn’t rely on me. He would jump out of his chair, approach the television and listen, almost pressing his ear against the screen.

The tone used in the Soviet Union to broadcast events in Israel, how those events were distorted was common knowledge. Grandpa certainly understood that very well, but his desire to hear at least something about our ancient homeland won out over his common sense. But then he would unburden himself, cursing ‘those damn anti-Semites” with all his might.

Meanwhile, Grandma Lisa who had already reached the bedroom, was making herself comfortable, sitting on the bed and changing for the night, all the while demanding sympathy, pity and recognition of her accomplishments. Since she didn’t have an audience and, perhaps taking into account that Grandpa and I weren’t far away, she talked to herself:

“Oy, how tired I am. Should someone my age work like this? Of course not. Oy, oy, oy, it got to me again.” That was her “spondulosis” remembered most unkindly. “Oy, it stings, it stings, what a curse!”

I knew very well what would follow. As soon as The Latest News and my work as narrator were over, Grandma’s very mournful call could be heard.

“Valery, bachim, let’s have a little massage.”

And I became a masseur.

Even though Grandma Lisa often used her “spondulosis” for certain purposes she considered diplomatic, as a weapon in “civil strife,” she actually had a considerably bent spine that made her back look like a small hillock. There was a board under the Grandma’s thin mattress, for the doctor had ordered her to sleep on a firm surface. In a word, Grandma really did suffer.

Up-down, up-down, to the left, to the right, to the left, to the right… My hand, coated with lotion, slid along Grandma’s curved back like a sled, as she moaned and groaned, albeit blissfully.

“A bit higher… more… harder! That’s it… good! That’s my boy! God grant you good health. When you’re not here, no one gives me a massage…”

Only when I worked as a masseur, did I receive so much praise and gratitude from Grandma. I continued to rub, my hand gradually becoming numb, and Grandma’s back turning red. To my surprise, it seemed to me that her back became more even, that the hillock almost disappeared.

* * *The last day before the wedding was particularly tense. Yura and I had to run small errands every now and then, and we tried to enjoy this vigorous activity as much as possible.

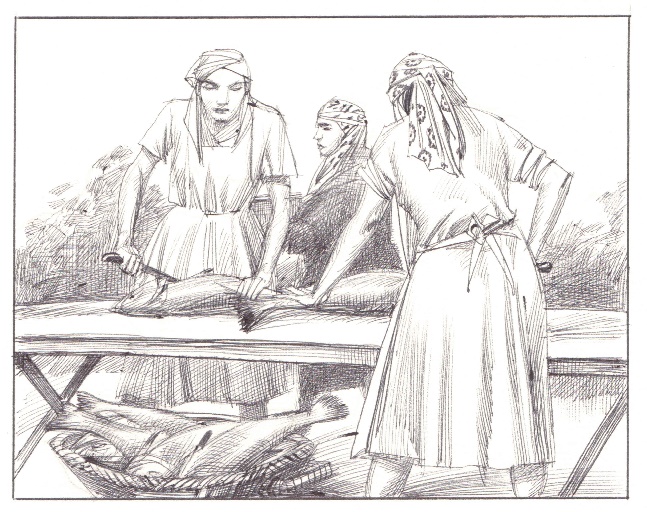

Mama and Valya scraped fish on the old wooden table with the carved legs near the trestle bed in the garden. Mama had arrived the day before from Chirchik after obtaining permission to miss work for two days.

There were two wicker baskets filled with big, fat silvery carp near the table. Now and then the women bent down, grabbed a heavy fish, dropped it with a thud onto the table, and large scales flew like spray in all directions.

Yura and I hung about near them waiting for the spoils.

The fish had been scraped. Now, they opened their bellies. O-one, and innards were pulled out. That was the moment we had been waiting for. Our mamas took the fish bladders out of the bundles of innards and threw them to us. A fish bladder is an oblong, pearly-yellowish container consisting of two parts and filled with air. It allows fish to stay afloat better. But we were attracted to a different quality: it was a perfect cracker. Put a bladder on asphalt, lift your leg and … pakh! Oh no, no words can express what that sounds like. One must simply hear it. It is so harsh, so booming that your ears get blocked for a second.

Bookh! Bookh! was heard from the table.

Now Mama, now Valya, and sometimes both of them together hit their knives with hammers, cutting through the sturdy fish spines, slicing the fish into chunks.

It was hard work. Their hands were stained with blood; fish scales were stuck to their hands, clothes, even faces. They were hot, and the flies that were attracted by the smell of the fish swarmed around and pestered them. But even that didn’t upset either Mama or Valya. They were very glad to be together, for they saw each other very rarely since we had moved to Chirchik.

Mama and Valya were friends. Their similar personalities, fates, even sorrows, along with being neighbors for many years, had bound them together. Valya was the only friend with whom Mama could share her trials and tribulations. She, on her part, heard out quite a few of Valya’s secrets. After marrying Father’s brother, Uncle Misha, Valya was, naturally, drawn into the whirlwind of the family squabbles. She was the only one in the whole family who didn’t take part in the hounding of Mama. Uncle Misha didn’t shun any “means of education” in trying to get his wife to join the clan. Sometimes, the pressure became so strong that the friends had to meet secretly, but their friendship endured.

Now, the two kelinkas – that’s what they called daughters-in-law in these parts – were getting ready to meet a third one. What would she be like, this young daughter-in-law? Would she become their friend? Or would she prefer to join the majority? That’s what bothered our mamas, what they pondered while their hands were busy preparing the fish for cooking.

Our mamas discussed everything, not even feeling awkward about having Yura and me around. It made no difference, for we knew all their secrets. We saw how other relatives treated them, and we witnessed their hopeless and timid attempts to change this small hostile family commune for the better. And, of course, we sided with our mamas with all our hearts. Yura’s open rebelliousness, his quarrels with Grandma Lisa and Forelock were nothing but a desire to express it. I was timider and, perhaps, gentler. My protest began to reveal itself later.