Полная версия

Полная версияLectures on Language, as Particularly Connected with English Grammar.

Describing adjectives admit of variation to express different degrees of comparison. The regular degrees have been reckoned three; positive, comparative, and superlative. These are usually marked by changing the termination. The positive is determined by a comparison with other things; as, a great house, a small book, compared with others of their kind. This is truly a comparative degree. The comparative adds er; as, a greater house, a smaller book. The superlative, est; as, the greatest house, the smallest book.

Several adjectives express a comparison less than the positive, others increase or diminish the regular degrees; as, whitish white, very white, pure white; whiter, considerable whiter, much whiter; whitest, the very whitest, much the whitest beyond all comparison, so that there can be none whiter, nor so white.

We make an aukward use of the words great and good, in the comparison of things; as, a good deal, or great deal whiter; a good many men, or a great many men. As we never hear of a small deal, or a bad deal whiter, nor of a bad many, nor little many, it would be well to avoid such phrases.

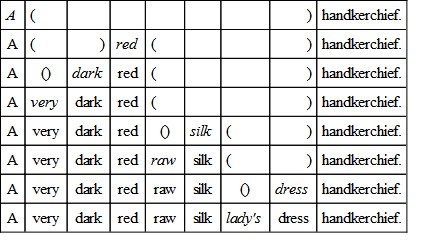

The words which are added to other adjectives, to increase or diminish the comparison, or assist in their definition, may properly be called secondary adjectives, for such is their character. They do not refer to the thing to be defined or described, but to the adjective which is affected, in some way, by them. They are easily distinguished from the rest by noticing this fact. Take for example: "A very dark red raw silk lady's dress handkerchief." The resolution of this sentence would stand thus:

We might also observe that hand is an adjective, compounded by use with kerchief. It is derived from the french word couvrir, to cover, and chef, the head. It means a head dress, a cloth to cover, a neck cloth, a napkin. By habit we apply it to a single article, and speak of neck handkerchief.

The nice shade of meaning, and the appropriate use of adjectives, is more distinctly marked in distinguishing colors than in any thing else, for the simple reason, that there is nothing in nature so closely observed. For instance, take the word green, derived from grain, because it is grain color, or the color of the fair carpet of nature in spring and summer. But this hue changes from the deep grass green, to the light olive, and words are chosen to express the thousand varying tints produced by as many different objects. In the adaptation of language to the expression of ideas, we do not separate these shades of color from the things in which such colors are supposed to reside. Hence we talk of grass, pea, olive, leek, verdigris, emerald, sea, and bottle green; also, of light, dark, medium; very light, or dark grass, pea, olive, or invisible green.

Red, as a word, means rayed. It describes the appearance or substance produced when rayed, reddened, or radiated by the morning beams of the sun, or any other radiating cause.

Wh is used for qu, in white, which means quite, quited, quitted, cleared, cleansed of all color, spot, or stain.

Blue is another spelling for blew. Applied to color, it describes something in appearance to the sky, when the clouds and mists are blown away, and the clear blue ether appears.

You will be pleased with the following extract from an eloquent writer of the last century,9 who, tho somewhat extravagant in some of his speculations, was, nevertheless, a close observer of nature, which he studied as it is, without the aid of human theories. The beauty of the style, and the correctness of the sentiment, will be a sufficient apology for its length.

"We shall employ a method, not quite so learned, to convey an idea of the generation of colors, and the decomposition of the solar ray. Instead of examining them in a prism of glass, we shall consider them in the heavens, and there we shall behold the five primordial colours unfold themselves in the order which we have indicated.

"In a fine summer's night, when the sky is loaded only with some light vapours, sufficient to stop and to refract the rays of the sun, walk out into an open plain, where the first fires of Aurora may be perceptible. You will first observe the horizon whiten at the spot where she is to make her appearance; and this radiance, from its colour, has procured for it, in the French language, the name of aube, (the dawn,) from the Latin word alba, white. This whiteness insensibly ascends in the heavens, assuming a tint of yellow some degrees above the horizon; the yellow as it rises passes into orange; and this shade of orange rises upward into the lively vermilion, which extends as far as the zenith. From that point you will perceive in the heavens behind you the violet succeeding the vermilion, then the azure, after it the deep blue or indigo colour, and, last of all, the black, quite to the westward.

"Though this display of colours presents a multitude of intermediate shades, which rapidly succeed each other, yet at the moment the sun is going to exhibit his disk, the dazzling white is visible in the horizon, the pure yellow at an elevation of forty-five degrees; the fire color in the zenith; the pure blue forty-five degrees under it, toward the west; and in the very west the dark veil of night still lingering on the horizon. I think I have remarked this progression between the tropics, where there is scarcely any horizontal refraction to make the light prematurely encroach on the darkness, as in our climates.

"Sometimes the trade-winds, from the north-east or south-east, blow there, card the clouds through each other, then sweep them to the west, crossing and recrossing them over one another, like the osiers interwoven in a transparent basket. They throw over the sides of this chequered work the clouds which are not employed in the contexture, roll them up into enormous masses, as white as snow, draw them out along their extremities in the form of a crupper, and pile them upon each other, moulding them into the shape of mountains, caverns, and rocks; afterwards, as evening approaches, they grow somewhat calm, as if afraid of deranging their own workmanship. When the sun sets behind this magnificent netting, a multitude of luminous rays are transmitted through the interstices, which produce such an effect, that the two sides of the lozenge illuminated by them have the appearance of being girt with gold, and the other two in the shade seem tinged with ruddy orange. Four or five divergent streams of light, emanated from the setting sun up to the zenith, clothe with fringes of gold the undeterminate summits of this celestial barrier, and strike with the reflexes of their fires the pyramids of the collateral aerial mountains, which then appear to consist of silver and vermilion. At this moment of the evening are perceptible, amidst their redoubled ridges, a multitude of valleys extending into infinity, and distinguishing themselves at their opening by some shade of flesh or of rose colour.

"These celestial valleys present in their different contours inimitable tints of white, melting away into white, or shades lengthening themselves out without mixing over other shades. You see, here and there, issuing from the cavernous sides of those mountains, tides of light precipitating themselves, in ingots of gold and silver, over rocks of coral. Here it is a gloomy rock, pierced through and through, disclosing, beyond the aperture, the pure azure of the firmament; there it is an extensive strand, covered with sands of gold, stretching over the rich ground of heaven; poppy-coloured, scarlet, and green as the emerald.

"The reverberation of those western colours diffuses itself over the sea, whose azure billows it glazes with saffron and purple. The mariners, leaning over the gunwale of the ship, admire in silence those aerial landscapes. Sometimes this sublime spectacle presents itself to them at the hour of prayer, and seems to invite them to lift up their hearts with their voices to the heavens. It changes every instant into forms as variable as the shades, presenting celestial colors and forms which no pencil can pretend to imitate, and no language can describe.

"Travellers who have, at various seasons, ascended to the summits of the highest mountains on the globe, never could perceive, in the clouds below them, any thing but a gray and lead-colored surface, similar to that of a lake. The sun, notwithstanding, illuminated them with his whole light; and his rays might there combine all the laws of refraction to which our systems of physics have subjected them. Hence not a single shade of color is employed in vain, through the universe; those celestial decorations being made for the level of the earth, their magnificent point of view taken from the habitation of man.

"These admirable concerts of lights and forms, manifest only in the lower region of the clouds the least illuminated by the sun, are produced by laws with which I am totally unacquainted. But the whole are reducible to five colors: yellow, a generation from white; red, a deeper shade of yellow; blue, a strong tint of red; and black, the extreme tint of blue. This progression cannot be doubted, on observing in the morning the expansion of the light in the heavens. You there see those five colors, with their intermediate shades, generating each other nearly in this order: white, sulphur yellow, lemon yellow, yolk of egg yellow, orange, aurora color, poppy red, full red, carmine red, purple, violet, azure, indigo, and black. Each color seems to be only a strong tint of that which precedes it, and a faint tint of that which follows; thus the whole together appear to be only modulations of a progression, of which white is the first term, and black the last.

"Indeed trade cannot be carried on to any advantage, with the Negroes, Tartars, Americans, and East-Indians, but through the medium of red cloths. The testimonies of travellers are unanimous respecting the preference universally given to this color. I have indicated the universality of this taste, merely to demonstrate the falsehood of the philosophic axiom, that tastes are arbitrary, or that there are in Nature no laws for beauty, and that our tastes are the effects of prejudice. The direct contrary of this is the truth; prejudice corrupts our natural tastes, otherwise the same over the whole earth.

"With red Nature heightens the brilliant parts of the most beautiful flowers. She has given a complete clothing of it to the rose, the queen of the garden: and bestowed this tint on the blood, the principle of life in animals: she invests most of the feathered race, in India, with a plumage of this color, especially in the season of love; and there are few birds without some shades, at least, of this rich hue. Some preserve entirely the gray or brown ground of their plumage, but glazed over with red, as if they had been rolled in carmine; others are besprinkled with red, as if you had blown a scarlet powder over them.

"The red (or rayed) color, in the midst of the five primordial colors, is the harmonic expression of them by way of excellence; and the result of the union of two contraries, light and darkness. There are, besides, agreeable tints, compounded of the oppositions of extremes. For example, of the second and fourth color, that is, of yellow and blue, is formed green, which constitutes a very beautiful harmony, and ought, perhaps, to possess the second rank in beauty, among colors, as it possesses the second in their generation. Nay, green appears to many, if not the most beautiful tint, at least the most lovely, because it is less dazzling than red, and more congenial to the eye."

Many words come under the example previously given to illustrate the secondary character of adjectives, which should be carefully noticed by the learner, to distinguish whether they define or describe things, or are added to increase the distinction made by the adjectives themselves, for both defining and describing adjectives admit of this addition; as, old English coin, New England rebelion; a mounted whip, and a gold mounted sword—not a gold sword; a very fine Latin scholar.

Secondary adjectives, also, admit of comparison in various ways; as, dearly beloved, a more beloved, the best beloved, the very best beloved brother.

Words formerly called "prepositions," admit of comparison, as I have before observed. "Benhadad fled into an inner chamber." The inner temple. The inmost recesses of the heart. The out fit of a squadron. The outer coating of a vessel, or house. The utmost reach of grammar. The up and down hill side of a field. The upper end of the lot. The uppermost seats. A part of the book. Take it farther off. The off cast. India beyond the Ganges. Far beyond the boundaries of the nation. I shall go to the city. I am near to the town. Near does not qualify the verb, for it has nothing to do with it. I can exist in one place as well as another. It is below the surface; very far below it. It is above the earth—"high above all height."

Such expressions frequently occur in the expression of ideas, and are correctly understood; as difficult as it may have been to describe them with the theories learned in the books—sometimes calling them one thing, sometimes another—when their character and meaning was unchanged, or, according to old systems, had "no meaning at all of their own!"

But I fear I have gone far beyond your patience, and, perhaps, entered deeper into this subject than was necessary, to enable you to discover my meaning. I desired to make the subject as distinct as possible, that all might see the important improvement suggested. I am apprehensive even now, that some will be compelled to think many profound thoughts before they will see the end of the obscurity under which they have long been shrouded, in reference to the false rules which they have been taught. But we have one consolation—those who are not bewildered by the grammars they have tried in vain to understand, will not be very likely to make a wrong use of adjectives, especially if they have ideas to express; for there is no more danger of mistaking an adjective for a noun, or verb, than there is of mistaking a horse chestnut for a chestnut horse.

In our next we shall commence the consideration of Verbs, the most important department in the science of language, and particularly so in the system we are defending. I hope you have not been uninterested thus far in the prosecution of the subject of language, and I am confident you will not be in what remains to be said upon it. The science, so long regarded dry and uninteresting, becomes delightful and easy; new and valuable truths burst upon us at each advancing step, and we feel to bless God for the ample means afforded us for obtaining knowledge from, and communicating it to others, on the most important affairs of time and eternity.

LECTURE VIII.

ON VERBS

Unpleasant to expose error. – Verbs defined. – Every thing acts. – Actor and object. – Laws. – Man. – Animals. – Vegetables. – Minerals. – Neutrality degrading. – Nobody can explain a neuter verb. – One kind of verbs. – You must decide. – Importance of teaching children the truth. – Active verbs. – Transitive verbs false. – Samples. – Neuter verbs examined. – Sit. – Sleep. – Stand. – Lie. – Opinion of Mrs. W. – Anecdote.

We now come to the consideration of that class of words which in the formation of language are called Verbs. You will allow me to bespeak your favorable attention, and to insist most strenuously on the propriety of a free and thoro examination into the nature and use of these words. I shall be under the necessity of performing the thankless task of exposing the errors of honest, wise, and good men, in order to remove difficulties which have long existed in works on language, and clear the way for a more easy and consistent explanation of this interesting and essential department of literature. I regret the necessity for such labors; but no person who wishes the improvement of mankind, or is willing to aid the growth of the human intellect, in its high aspirations after truth, knowledge, and goodness, should shrink from a frank exposition of what he deems to be error, nor refuse his assistance, feeble tho it may be, in the establishment of correct principles.

In former lectures we have confined our remarks to things and a description of their characters and relations, so that every entity of which we can conceive a thought, or concerning which we can form an expression, has been defined and described in the use of nouns and adjectives. Every thing in creation, of which we think, material or immaterial, real or imaginary, and to which we give a name, to represent the idea of it, comes under the class of words called nouns. The words which specify or distinguish one thing from another, or describe its properties, character, or relations, are designated as adjectives. There is only one other employment left for words, and that is the expression of the actions, changes, or inherent tendencies of things. This important department of knowledge is, in grammar, classed under the head of Verbs.

Verb is derived from the Latin verbum, which signifies a word. By specific application it is applied to those words only which express action, correctly understood; the same as Bible, derived from the Greek "biblos" means literally the book, but, by way of eminence, is applied to the sacred scriptures only.

This interesting class of words does not deviate from the correct principles which we have hitherto observed in these lectures. It depends on established laws, exerted in the regulation of matter and thought; and whoever would learn its sublime use must be a close observer of things, and the mode of their existence. The important character it sustains in the production of ideas of the changes and tendencies of things and in the transmission of thought, will be found simple, and obvious to all.

Things exist; Nouns name them.

Things differ; Adjectives define or describe them.

Things act; Verbs express their actions.

All Verbs denote action.

By action, we mean not only perceivable motion, but an inherent tendency to change, or resist action. It matters not whether we speak of animals possessed of the power of locomotion; of vegetables, which send forth their branches, leaves, blossoms, and fruits; or of minerals, which retain their forms, positions, and properties. The same principles are concerned, the same laws exist, and should be observed in all our attempts to understand their operations, or employ them in the promotion of human good. Every thing acts according to the ability it possesses; from the small particle of sand, which occupies its place upon the sea shore, up thro the various gradation of being, to the tall archangel, who bows and worships before the throne of the uncreated Cause of all things and actions which exist thro out his vast dominions.

As all actions presuppose an actor, so every action must result on some object. No effect can exist without an efficient cause to produce it; and no cause can exist without a corresponding effect resulting from it. These mutual relations, helps, and dependencies, are manifest in all creation. Philosophy, religion, the arts, and all science, serve only to develope these primary laws of nature, which unite and strengthen, combine and regulate, preserve and guide the whole. From the Eternal I AM, the uncreated, self-existent, self-sustaining Cause of all things, down to the minutest particle of dust, evidences may be traced of the existence and influence of these laws, in themselves irresistible, exceptionless, and immutable. Every thing has a place and a duty assigned it; and harmony, peace, and perfection are the results of a careful and judicious observance of the laws given for its regulation. Any infringement of these laws will produce disorder, confusion, and distraction.

Man is made a little lower than the angels, possessed of a mind capable of reason, improvement, and happiness; an intellectual soul inhabiting a mortal body, the connecting link between earth and heaven—the material and spiritual world. As a physical being, he is subject, in common with other things, to the laws which regulate matter: as an intellectual being, he is governed by the laws which regulate mind: as possessed of both a body and mind, a code of moral laws demand his observance in all the social relations and duties of life. Obedience to these laws is the certain source of health of body, and peace of mind. An infringement of them will as certainly be attended with disease and suffering to the one, and sorrow and anguish to the other.

Lower grades of animals partake of many qualities in common with man. In some they are deficient; in others they are superior. Some animals are possessed of all but reason, and even in that, the highest of them come very little short of the lowest of the human species. If they have not reason, they possess an instinct which nearly approaches it. These qualities dwindle down gradually thro the various orders and varieties of animated nature, to the lowest grade of animalculæ, a multitude of which may inhabit a single drop of water; or to the zoophytes and lythophytes, which form the connecting link between the animal and vegetable kingdom; as the star-fish, the polypus, and spunges. Then strike off into another kingdom, and observe the laws vegetable life. Mark the tall pine which has grown from a small seed which sent forth its root downwards and its trunk upwards, drawing nourishment from earth, air, and water, till it now waves its top to the passing breeze, a hundred feet above this dirty earth: or the oak or olive, which have maintained their respective positions a dozen centuries despite the operations of wind and weather, and have shed their foliage and their seeds to propagate their species and extend their kinds to different places. While a hundred generations have lived and died, and the country often changed masters, they resist oppression, scorn misrule, and retain rights and privileges which are slowly encroached upon by the inroads of time, which will one day triumph over them, and they fall helpless to the earth, to submit to the chemical operations which shall dissolve their very being and cause them to mingle with the common dust, yielding their strength to give life and power to other vegetables which shall occupy their places.10 Or mark the living principle in the "sensitive plant," which withers at every touch, and suffers long ere it regains its former vigor.

Descend from thence, down thro the various gradations of vegetable life, till you pass the narrow border and enter the mineral world. Here you will see displayed the same sublime principle, tho in a modified degree. Minerals assume different shapes, hues and relations; they increase and diminish, attach and divide under various circumstances, all the while retaining their identity and properties, and exerting their abilities according to the means they possess, till compelled to yield to a superior power, and learn to submit to the laws which operate in every department of this mutable world.

Every thing acts according to the ability God has bestowed upon it; and man can do no more. He has authority over all things on earth, and yet he is made to depend upon all. His authority extends no farther than a privilege, under wholesome restrictions, of making the whole subservient to his real good. When he goes beyond this, he usurps a power which belongs not to him, and the destruction of his happiness pays the forfeit of his imprudence. The injured power rises triumphant over the aggressor, and the glory of God's government, in the righteous and immediate execution of his laws, is clearly revealed. So long as man obeys the laws which regulate health, observes temperance in all things, uses the things of this world as not abusing them, he is at rest, he is blessed, he is happy: but no sooner has he violated heaven's law than he becomes the slave, and the servant assumes the master. But I am digressing. I would gladly follow this subject further, but I shall go beyond my limits, and, it may be, your patience.