Полная версия

Полная версияLectures on Language, as Particularly Connected with English Grammar.

Whether is which either. "Shew whether of these two thou hast chosen."—Acts 1: 24. It is more frequently applied in modern times to circumstance and events than to persons and things. "I will let you know whether I will or will not adopt it," one or the other.

Together signifies two or more united. Gethered is the past participle of gather.

"As Mailie, an' her lambs thegither,Were ae day nibbling on the tether."Burns.Ever means time, age, period. It originally and essentially signified life. For ever is for the age or period. For ever and ever, to the ages of ages. Ever-lasting is age-lasting. Ever-lasting hills, snows, landmarks, etc.

Never, ne-ever, not ever, at no time, age or period.

When-ever.—At what point or space of time or age.

What-ever.—What thing, fact, circumstance, or event.

Where-ever.—To, at, or in what place, period, age, or time.

Whither-so-ever, which-way-so-ever, where-so-ever, never-the-less, etc. need only be analyzed, and their meaning will appear obvious to all.

Oft, often, oft-times, often-times, can be understood by all, because the noun to which they belong is oft-en retained in practice.

Once, twice, at one time, two times.

Hence, thence, whence, from this, that, or what, place, spot, circumstance, post, or starting place.

Hence-for-ward, hence-forth, in time to come, after this period.

Here-after, after this era, or present time.

Hither, to this spot or place. Thither, to that place. Hither-to, hither-ward, etc. the same as to you ward, or to God ward, still retained in our bibles.

Per-haps, it may hap. Perchance, peradventure, by chance, by adventure. The latin per means by.

Not, no ought, not any, nothing. It is a compound of ne and ought or aught.

Or is a contraction from other, and nor from ne-or, no-or, no other.

No-wise, no ways. I will go, or, other-wise, in another way or manner, you must go.

Than, the ane, the one, that one, alluding to a particular object with which a comparison is made; as, This book is larger than that bible. That one bible, this book is larger. It is always used with the comparative degree, to define particularly the object with which the comparison is made. Talent is better than flattery. Than flattery, often bestowed regardless of merit, talent is better.

As is an adjective, in extensive use. It means the, this, that, these, the same, etc. It is a defining word of the first kind. You practice as you have been taught—the same duties or principles understood. We use language as we have learned it; in the same way or manner. It is often associated with other words to particularly specify the way, manner, or degree, in which something is done or compared. I can go as well as you. In the same well, easy, convenient way or manner you can go, I can go in the same way. He was as learned, as pious, as benevolent, as brave, as faithful, as ardent. These are purely adjectives, used to denote the degree of the likeness or similarity between the things compared. Secondary words are often added to this, to aid the distinction or definition; as, (the same illustrated,) He is just as willing. I am quite as well pleased without it. As, like many other adjectives, often occurs without a noun expressed, in which case it was formerly parsed by Murray himself as (like, or the same) a relative pronoun; as, "And indeed it seldom at any period extends to the tip, as happens in acute diseases."—Dr. Sweetster. "The ground I have assumed is tenable, as will appear."—Webster. "Bonaparte had a special motive in decorating Paris, for 'Paris is France, as has often been observed."—Channing. "The words are such as seem."—Murray's Reader! p. 16, intro.

So has nearly the same signification as the word last noticed, and is frequently used along with it, to define the other member of the comparison. As far as I can understand, so far I approve. As he directed, so I obeyed. It very often occurs as a secondary adjective; as, "In pious and benevolent offices so simple, so minute, so steady, so habitual, that they will carry," etc. "He pursued a course so unvarying."—Channing.

These words are the most important of any small ones in our vocabulary, because (for this cause, be this the cause, this is the cause) they are the most frequently used; and yet there are no words so little understood, or so much abused by grammarians, as these are.

We have barely time to notice the remaining parts of speech. "Conjunctions" are defined to be a "part of speech void of signification, but so formed as to help signification, by making two or more significant sentences to be one significant sentence." Mr. Harris gives about forty "species." Murray admits of only the dis-junctive and copulative, and reduces the whole list of words to twenty-four. But what is meant by a dis-junctive con-junctive word, is left for you to determine. It must be in keeping with indefinite defining articles, and post-positive pre-positions. He says, "it joins words, but disjoins the sense."22 And what is a word with out sense," pray tell us? If "words are the signs of ideas," how, in the name of reason, can you give the sign and separate the sense? You can as well separate the shadow from the substance, or a quality from matter.

We have already noticed Rule 18, which teaches the use of conjunctions. Under that rule, you may examine these examples. "As it was in the beginning, is now, and ever shall be."—Common Prayer. "What I do, have done, or may hereafter do, has been, and will always be matter of inclination, the gratifying of which pays itself: and I have no more merit in employing my time and money in the way I am known to do, than another has in other occupations."—Howard.

The following examples must suffice.

If. This word is derived from the saxon gifan, and was formerly written giff, gyff, gif, geve, give, yiff, yef, yeve. It signifies give, grant, allow, suppose, admit, and is always a verb in the imperative mood, having the following sentence or idea for its object. "If a pound of sugar cost ten cents, what will ten pounds cost?" Give, grant, allow, suppose, (the fact,) one pound cost, etc. In this case the supposition which stands as a predicate—one pound of sugar cost ten cents, is the object of if—the thing to be allowed, supposed, or granted, and from which the conclusion as to the cost of ten pounds is to be drawn.

"He will assist us if he has the means." Allow, admit, (the fact,) he has the means, he will assist us.

"Gif luf be vertew, than is it leful thing;Gif it be vice, it is your undoing."Douglas p. 95."Ne I ne wol non reherce, yef that I may."Chaucer."She was so charitable and so pytousShe wolde wepe yf that she sawe a mousCaught in a trappe, if it were deed or bledde."Prioresse."O haste and come to my master dear.""Gin ye be Barbara Allen."Burns.But. This word has two opposite significations. It is derived from two different radicals. But, from the saxon be and utan, out, means be out, leave out, save, except, omit, as, "all but one are here." Leave out, except, one, all are here.

"Heaven from all creation hides the book of fateAll but (save, except) the page prescribed our present state.""When nought but (leave out) the torrent is heard on the hill,And nought but (save) the nightingale's song in the grove.""Nothing but fear restrains him." In these cases the direct objects of the verb, the things to be omitted are expressed.

But is also derived from botan, which signifies to add, superadd, join or unite; as, in the old form of a deed, "it is butted and bounded as follows." Two animals butt their heads together. The butt of a log is that end which was joined to the stump. A butt, butment or a-butment is the joined end, where there is a connexion with something else. A butt of ridicule is an object to which ridicule is attached.

"Not only saw he all that was,But (add) much that never came to pass."M'Fingal.To button, butt-on, is derived from the same word, to join one side to the other, to fasten together. It was formerly spelled botan, boote, bote, bot, butte, bute, but. It is still spelled boot in certain cases as a verb; as,

"What boots it thee to fly from pole to pole,Hang o'er the earth, and with the planets roll?What boots ( ) thro space's fartherest bourns to roam,If thou, O man, a stranger art at home?"Grainger."If love had booted care or cost."A man exchanged his house in the city for a farm, and received fifty dollars to boot; to add to his property, and make the exchange equal.

Let presents the same construction in form and meaning as but, for it is derived from two radicals of opposite significations. It means sometimes to permit or allow; as, let me go; let me have it; and to hinder or prevent; as, "I proposed to come unto you, but (add this fact) I was let hitherto."—Rom. 1: 13. "He who now letteth, will let until he be taken out of the way."—2 Thess. 2: 7.

And is a past participle signifying added, one-ed, joined. It was formerly placed after the words; as, "James, John, David, and, (united to-gether-ed,) go to school." We now place it before the last word.

Tho, altho, yet. "Tho (admit, allow, the fact) he slay me, yet (get, have, know, the fact) I will trust in him." Yes is from the same word as yet. It means get or have my consent to the question asked. Nay is the opposite of yes, ne-aye, nay, no. The ayes and noes were called for.

I can pursue this matter no farther. The limits assigned me have been overrun already. What light may have been afforded you in relation to these words, will enable you to discover that they have meaning which must be learned before they can be explained correctly; that done, all difficulty is removed.

Interjections deserve no attention. They form no part of language, but may be used by beasts and birds as well as by men. They are indistinct utterances of emotions, which come not within the range of human speech.

1

The reader is referred to "The Red Book," by William Bearcroft, revised by Daniel H. Barnes, late of the New-York High School, as a correct system of teaching practical orthography.

2

Gall, Spurzheim, and Combe, have reflected a light upon the science of the mind, which cannot fail of beneficial results. Tho the doctrines of phrenology, as now taught, may prove false—which is quite doubtful—or receive extensive modifications, yet the consequences to the philosophy of the mind will be vastly useful. The very terms employed to express the faculties and affections of the mind, are so definite and clear, that phrenology will long deserve peculiar regard, if for no other reason than for the introduction of a vocabulary, from which may be selected words for the communication of ideas upon intellectual subjects.

3

Metaphysics originally signified the science of the causes and principles of all things. Afterwards it was confined to the philosophy of the mind. In our times it has obtained still another meaning. Metaphysicians became so abstruse, bewildered, and lost, that nobody could understand them; and hence, metaphysical is now applied to whatever is abstruse, doubtful, and unintelligible. If a speaker is not understood, it is because he is too metaphysical. "How did you like the sermon, yesterday?" "Tolerably well; but he was too metaphysical for common hearers." They could not understand him.

4

In this respect, many foreign languages possess a great advantage over ours. They can augment or diminish the same word to increase or lessen the meaning. For instance; in the Spanish, we can say Hombre, a man; Hombron, a large man; Hombrecito, a young man, or youth; Hombrecillo, a miserable little man; Pagaro, a bird; Pagarito, a pretty little bird; Perro, a dog; Perrillo, an ugly little dog; Perrazo, a large dog.

The Indian languages admit of diminutives in a similar way. In the Delaware dialect, they are formed by the suffix tit, in the class of animate nouns; but by es, to the inanimate; as, Senno, a man; Sennotit, a little man; Wikwam, a house; Wikwames, a small house.—Enc. Amer. Art. Indian Languages, vol. 6, p. 586.

5

Mr. Harris, in his "Hermes," says, "A preposition is a part of speech, devoid itself of signification; but so formed as to unite two words that are significant, and that refuse to coalesce or unite themselves."

Mr. Murray says, "Prepositions serve to connect words with one another, and show the relation between them."

6

"Me thou shalt use in what thou wilt, and doe that with a slender twist, that none can doe with a tough with."

Euphues and his England, p. 136.

"They had arms under the straw in the boats, and had cut the withes that held the oars of the town boats, to prevent any pursuit."

Ludlow's Memoirs, p. 435.

"The only furniture belonging to the houses, appears to be an oblong vessel made of bark, by tying up the ends with a withe."

Cooke's Description of Botany Bay.

7

See Galatians, chap. 1, verse 15. "When it pleased God, who separated me," &c.

8

Acts, xvii, 28.

9

St. Pierre's Studies of Nature.—Dr. Hunter's translation, pp. 172-176.

10

It is reported on very good authority that the same olive trees are now standing in the garden of Gethsemane under which the Saviour wept and near which he was betrayed. This is rendered more probable from the fact, that a tax is laid, by the Ottoman Porte, on all olive trees planted since Palestine passed into the possession of the Turks, and that several trees standing in Gethsemane do not pay such tribute, while all others do.

11

We do not assent to the notions of ancient philosophers and poets, who believed the doctrine that the world is animated by a soul, like the human body, which is the spirit of Deity himself; but that by the operation of wise and perfect laws, he exerts a supervision in the creation and preservation of all things animate and inanimate. Virgil stated the opinions of his times, in his Æneid, B. VI. l. 724.

"Principio cœlum, ac terras, camposque liquentes,

Lucentemque globum, Lunæ, Titaniaque astra

Spiritus intus alit, totamque infusa per artus

Mens agitat molem, et magno se corpore miscet."

"Know, first, that heaven, and earth's compacted frame,

And flowing waters, and the starry flame,

And both the radiant lights, one common soul

Inspires and feeds—and animates the whole.

This active mind, infused thro all the space,

Unites and mingles with the mighty mass."

Dryden, b. VI. l. 980.

This sentiment, he probably borrowed from Pythagoras and Plato, who argue the same sentiment, and divide this spirit into "intellectus, intelligentia, et natura"—intellectual, intelligent, and natural. Whence, "Ex hoc Deo, qui est mundi anima: quasi decerptæ particulæ sunt vitæ hominum et pecudum." Or, "Omnia animalia ex quatuor elementis et divino spiritu constare manifestum est. Trahunt enim a terra carnem, ab aqua humorem, ab ære anhelitum, ab igne fervorem, a divino spiritu ingenium."—Timeus, chap. 24, and Virgil's Geor. b. 4, l. 220, Dryden's trans. l. 322.

Pope alludes to the same opinion in these lines:

"All are but parts of one stupendous whole.

Whose body nature is, and God the soul."

12

Page 41.

13

Exodus, iii. 2, 3.

14

Cardell's grammar.

15

The Jews long preserved this name in Samaritan letters to keep it from being known to strangers. The modern Jews affirm that by this mysterious name, engraven on his rod, Moses performed the wonders recorded of him; that Jesus stole the name from the temple and put it into his thigh between the flesh and skin, and by its power accomplished the miracles attributed to him. They think if they could pronounce the word correctly, the very heavens and earth would tremble, and angels be filled with terror.

16

Plutarch says, "This title is not only proper but peculiar to God, because He alone is being; for mortals have no participation of true being, because that which begins and ends, and is constantly changing, is never one nor the same, nor in the same state. The deity on whose temple this word was inscribed was called Apollo, Apollon, from a negative and pollus, many, because God is one, his nature simple, and uncompounded."—Vide, Clark's Com.

17

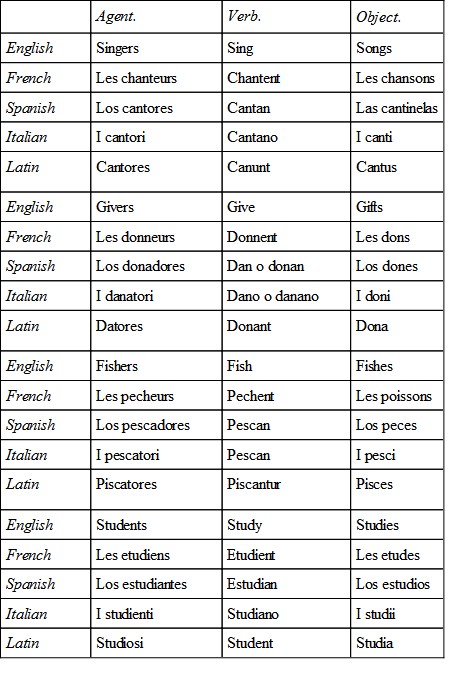

The same fact may be observed in other languages, for all people form language alike, in a way to correspond with their ideas. The following hasty examples will illustrate this point.

18

Mr. Murray says, "These compounds," have, shall, will, may, can, must, had, might, could, would, and should, which he uses as auxiliaries to help conjugate other verbs, "are, however, to be considered as different forms of the same verb." I should like to know, if these words have any thing to do with the principal verbs; if they only alter the form of the verb which follows them. I may, can, must, shall, will, or do love. Are these only different forms of love? or rather, are they not distinct, important, and original verbs, pure and perfect in and of themselves? Ask for their etymons and meaning, and then decide.

19

Diversions of Purley, vol. 1, p. 77.

20

Dr. Edwards observes, in a communication to the Connecticut Society of Arts and Sciences, from personal knowledge, that "the Mohegans (Indians) have no adjectives in all their language. Altho it may at first seem not only singular and curious, but impossible, that a language should exist without adjectives, yet it is an indubitable fact." But it is proved that in later times the Indians employ adjectives, derived from nouns or verbs, as well as other nations. Altho many of their dialects are copious and harmonious, yet they suffered no inconvenience from a want of contracted words and phrases. They added the ideas of definition and description to the things themselves, and expressed them in the same word, in a modified form.

21

Matthew, chap. 24, v. 48.

22

Examples of a dis-junctive conjunction. "They came with her, but they went without her."—Murray.

Murray is wrong, and Cardell is right. The simplifiers are wrong, but their standard is so likewise.

"Me he restored to my office, and him he hanged."—Pharaoh's Letter.