Полная версия

Полная версияПолная версия:

Rambles and Recollections of an Indian Official

Though I reprobate that wanton severity of discipline in which the substance is sacrificed to the form, in which unavoidable and trivial offences are punished as deliberate and serious crimes, and the spirit of the soldier is entirely disregarded, while the motion of his limbs, cut of his whiskers, and the buttons of his coat are scanned with microscopic eye, I must not be thought to advocate idleness. If we find the sepoys of a native regiment, as we sometimes do at a healthy and cheap station, become a little unruly like schoolboys, and ask an old native officer the reason, he will probably answer others as he has me by another question, 'Ghora ārā kyūn? Pānī sarā kyūn?' 'Why does the horse become vicious? Why does the water become putrid?'-For want of exercise. Without proper attention to this exercise no regiment is ever kept in order; nor has any commanding officer ever the respect or the affection of his men unless they see that he understands well all the duties which his Government entrusts to him, and is resolved to have them performed in all situations and under all circumstances. There are always some bad characters in a regiment, to take advantage of any laxity of discipline, and lead astray the younger soldiers, whose spirits have been rendered exuberant by good health and good feeding; and there is hardly any crime to which they will not try to excite these young men, under an officer careless about the discipline of his regiment, or disinclined, from a mistaken esprit de corps, or any other cause, to have those crimes traced home to them and punished.1120

There can be no question that a good tone of feeling between the European officers and their men is essential to the well-being of our native army; and I think I have found this tone somewhat impaired whenever our native regiments are concentrated at large stations. In such places the European society is commonly large and gay; and the officers of our native regiments become too much occupied in its pleasures and ceremonies to attend to their native officers or sepoys. In Europe there are separate classes of people who subsist by catering for the amusements of the higher classes of society, in theatres, operas, concerts, balls, &c., &c.; but in India this duty devolves entirely upon the young civil and military officers of the Government, and at large stations it really is a very laborious one, which often takes up the whole of a young man's time. The ladies must have amusement; and the officers must find it for them, because there are no other persons to undertake the arduous duty. The consequence is that they often become entirely alienated from their men, and betray signs of the greatest impatience while they listen to the necessary reports of their native officers, as they come on or go off duty.1121

It is different when regiments are concentrated for active service. Nothing tends so much to improve the tone of feeling between the European officers and their men, and between European soldiers and sepoys, as the concentration of forces on actual service, where the same hopes animate, and the same dangers unite them in common bonds of sympathy and confidence. 'Utrique alteris freti, finitimos armis aut metu sub imperium cogere, nomen gloriamque sibi addidere.' After the campaigns under Lord Lake, a native regiment passing Dinapore, where the gallant King's 76th, with whom they had fought side by side, was cantoned, invited the soldiers to a grand entertainment provided for them by the sepoys. They consented to go on one condition—that the sepoys should see them all back safe before morning. Confiding in their sable friends, they all got gloriously drunk, but found themselves lying every man upon his proper cot in his own barracks in the morning. The sepoys had carried them all home upon their shoulders. Another native regiment, passing within a few miles of a hill on which they had buried one of their European officers after that war, solicited permission to go and make their 'salām' to the tomb, and all went who were off duty.1122 The system which now keeps the greater part of our native infantry at small stations of single regiments in times of peace tends to preserve this good tone of feeling between officers and men, at the same time that it promotes the general welfare of the country by giving confidence everywhere to the peaceful and industrious classes.

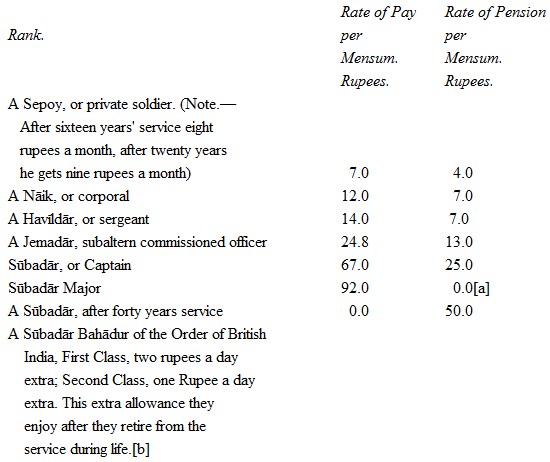

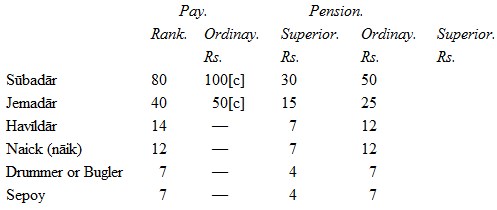

I will not close this chapter without mentioning one thing which I have no doubt every Company's officer in India will concur with me in thinking desirable to improve the good feeling of the native soldiery—that is, an increase in the pay of the Jemadārs. They are commissioned officers, and seldom attain the rank in less than from twenty-five to thirty years;1123 and they have to provide themselves with clothes of the same costly description as those of the Sūbadār; to be as well mounted, and in all respects to keep the same respectability of appearance, while their pay is only twenty-four rupees and a half a month; that is, ten rupees a month only more than they had been receiving in the grade of Havildārs, which is not sufficient to meet the additional expenses to which they become liable as commissioned officers. Their means of remittance to their families are rather diminished than increased by promotion, and but few of them can hope ever to reach the next grade of Sūbadār. Our Government, which has of late been so liberal to its native civil officers, will, I hope, soon take into consideration the claims of this class, who are universally admitted to be the worst paid class of native public officers in India. Ten rupees a month addition to their pay would be of great importance; it would enable them to impart some of the advantages of promotion to their families, and improve the good feeling of the circles around them towards the Government they serve.1124

CHAPTER 77

Invalid EstablishmentI have said nothing in the foregoing chapter of the invalid establishment, which is probably the greatest of all bonds between the Government and its native army, and consequently the greatest element in the 'spirit of discipline'. Bonaparte, who was, perhaps, with all his faults, 'the greatest man that ever floated on the tide of time', said at Elba, 'There is not even a village that has not brought forth a general, a colonel, a captain, or a prefect, who has raised himself by his especial merit, and illustrated at once his family and his country.' Now we know that the families and the village communities in which our invalid pensioners reside never read newspapers,1125 and feel but little interest in the victories in which these pensioners may have shared. They feel that they have no share in the éclat or glory which attend them; but they everywhere admire and respect the government which cherishes its faithful old servants, and enables them to spend the 'winter of their days' in the bosoms of their families; and they spurn the man who has failed in his duty towards that government in the hour of need.

No sepoy taken from the Rājpūt communities of Oudh or any other part of the country can hope to conceal from his family circle or village community any act of cowardice, or anything else which is considered disgraceful to a soldier, or to escape the odium which it merits in that circle and community.

In the year 1819 I was encamped near a village in marching through Oudh, when the landlord, a very cheerful old man, came up to me with his youngest son, a lad of eighteen years of age, and requested me to allow him (the son) to show me the best shooting grounds in the neighbourhood. I took my 'Joe Manton' and went out. The youth showed me some very good ground, and I found him an agreeable companion, and an excellent shot with his matchlock. On our return we found the old man waiting for us. He told me that he had four sons, all by God's blessing tall enough for the Company's service, in which one had attained the rank of 'havīldār' (sergeant), and two were still sepoys. Their wives and children lived with him; and they sent home every month two- thirds of their pay, which enabled him to pay all the rent of the estate and appropriate the whole of the annual returns to the subsistence and comfort of the numerous family. He was, he said, now growing old, and wished his eldest son, the sergeant, to resign the service and come home to take upon him the management of the estate; that as soon as he could be prevailed upon to do so, his old wife would permit my sporting companion, her youngest son, to enlist, but not before.

I was on my way to visit Fyzabad, the old metropolis of Oudh,1126 and on returning a month afterwards in the latter end of January, I found that the wheat, which was all then in ear, had been destroyed by a severe frost. The old man wept bitterly, and he and his old wife yielded to the wishes of their youngest son to accompany me and enlist in my regiment, which was then stationed at Partābgarh.1127

We set out, but were overtaken at the third stage by the poor old man, who told me that his wife had not eaten or slept since the boy left her, and that he must go back and wait for the return of his eldest brother, or she certainly would not live. The lad obeyed the call of his parents, and I never saw or heard of the family again.

There is hardly a village in the kingdom of Oudh without families like this depending upon the good conduct and liberal pay of sepoys in our infantry regiments, and revering the name of the government they serve, or have served. Similar villages are to be found scattered over the provinces of Bihār and Benares, the districts between the Ganges and Jumna, and other parts where Rājpūts and the other classes from which we draw our recruits have been long established as proprietors and cultivators of the soil.

These are the feelings on which the spirit of discipline in our native army chiefly depends, and which we shall, I hope, continue to cultivate, as we have always hitherto done, with care; and a commander must take a great deal of pains to make his men miserable, before he can render them, like the soldiers of Frederick, 'the irreconcilable enemies of their officers and their government'.

In the year 1817 I was encamped in a grove on the right bank of the Ganges below Monghyr,1128 when the Marquis of Hastings was proceeding up the river in his fleet, to put himself at the head of the grand division of the army then about to take the field against the Pindhārīs and their patrons, the Marāthā, chiefs. Here I found an old native pensioner, above a hundred years of age. He had fought under Lord Clive at the battle of Plassey, A.D. 1757, and was still a very cheerful, talkative old gentleman, though he had long lost the use of his eyes. One of his sons, a grey-headed old man, and a Sūbadār (captain) in a regiment of native infantry, had been at the taking of Java,1129 and was now come home on leave to visit his father. Other sons had risen to the rank of commissioned officers, and their families formed the aristocracy of the neighbourhood. In the evening, as the fleet approached, the old gentleman, dressed in his full uniform of former days as a commissioned officer, had himself taken out close to the bank of the river, that he might be once more during his life within sight of a British Commander-in-Chief, though he could no longer see one. There the old patriarch sat listening with intense delight to the remarks of the host of his descendants around him, as the Governor-General's magnificent fleet passed along,1130 every one fancying that he had caught a glimpse of the great man, and trying to describe him to the old gentleman, who in return told them (no doubt for the thousandth time) what sort of a person the great Lord Clive was. His son, the old Sūbadār, now and then, with modest deference, venturing to imagine a resemblance between one or the other, and his beau idéal of a great man, Lord Lake. Few things in India have interested me more than scenes like these.

I have no means of ascertaining the number of military pensioners in England or in any other European nation, and cannot, therefore, state the proportion which they bear to the actual number of forces kept up. The military pensioners in our Bengal establishment on the 1st of May, 1841, were 22,381; and the family pensioners, or heirs of soldiers killed in action, 1,730; total 24,111, out of an army of 82,027 men. I question whether the number of retired soldiers maintained at the expense of government bears so large a proportion to the number actually serving in any other nation on earth.1131 Not one of the twenty-four thousand has been brought on, or retained upon, the list from political interest or court favour; every one receives his pension for long and faithful services, after he has been pronounced by a board of European surgeons as no longer fit for the active duties of his profession; or gets it for the death of a father, husband, or son, who has been killed in the service of government.

All are allowed to live with their families, and European officers are stationed at central points in the different parts of the country where they are most numerous to pay them their stipends every six months. These officers are at— 1st, Barrackpore; 2nd, Dinapore; 3rd, Allahabad; 4th, Lucknow; 5th, Meerut. From these central points they move twice a year to the several other points within their respective circles of payment where the pensioners can most conveniently attend to receive their money on certain days, so that none of them have to go far, or to employ any expensive means to get it—it is, in fact, brought home as near as possible to their doors by a considerate and liberal government.1132

Every soldier is entitled to a pension when pronounced by a board of surgeons as no longer fit for the active duties of his profession, after fifteen years' active service; but to be entitled to the pension of his rank in the army, he must have served in such rank for three years. Till he has done so he is entitled only to the pension of that immediately below it. A sepoy gets four rupees a month, that is, about one-fourth more than the ordinary wages of common uninstructed labour throughout the country.1133 But it will be better to give the rate of pay of the native officers and men of our native infantry and that of their retired pensions in one table.

TABLE OF THE RATE OF PAY AND RETIRED PENSIONS OFTHE NATIVE OFFICERS AND SOLDIERS OF OUR NATIVE INFANTRY

a. I presume this means that no special rate of pension was fixed for the rank of Sūbadār Major.

b. The monthly rates of pay and pension now in force for native officers and men of the Bengal army are as follows:

c. Half of this rank in each regiment receive the higher rate of pay.

The circumstances which, in the estimation of the people, distinguish the British from all other rulers in India, and make it grow more and more upon their affections, are these: The security which public servants enjoy in the tenure of their office; the prospect they have of advancement by the gradation of rank; the regularity and liberal scale of their pay; and the provision for old age, when they have discharged the duties entrusted to them ably and faithfully.1134 In a native state almost every public officer knows that he has no chance of retaining his office beyond the reign of the present minister or favourite; and that no present minister or favourite can calculate upon retaining his ascendancy over the mind of his chief for more than a few months or years. Under us they see secretaries to government, members of council, and Governors-General themselves going out and coming into office without causing any change in the position of their subordinates, or even the apprehension of any change, as long as they discharge their duties ably and faithfully.

In a native state the new minister or favourite brings with him a whole host of expectants who must be provided for as soon as he takes the helm; and if all the favourites of his predecessor do not voluntarily vacate their offices for them, he either turns them out without ceremony, or his favourites very soon concoct charges against them, which causes them to be tumed out in due form, and perhaps put into jail till they have 'paid the uttermost farthing'. Under us the Governors-General, members of council, the secretaries of state,1135 the members of the judicial and revenue boards, all come into office and take their seats unattended by a single expectant. No native officer of the revenue or judicial department, who is conscious of having done his duty ably and honestly, feels the slightest uneasiness at the change. The consequence is a degree of integrity in public officers never before known in India, and rarely to be found in any other country. In the province where I now write,1136 which consists of six districts, there are twenty-two native judicial officers, Munsifs, Sadr Amīns, and Principal Sadr Amīns;1137 and in the whole province I have never heard a suspicion breathed against one of them; nor do I believe that the integrity of one of them is at this time suspected. The only one suspected within the two and a half years that I have been in the province was, I grieve to say, a Christian; and he has been removed from office, to the great satisfaction of the people, and is never to be employed again.1138 The only department in which our native public servants do not enjoy the same advantages of security in the tenure of their office, prospect of rise in the gradation of rank, liberal scale of pay, and provision for old age, is the police; and it is admitted on all hands that there they are everywhere exceedingly corrupt. Not one of them, indeed, ever thinks it possible that he can be supposed honest; and those who really are so are looked upon as a kind of martyrs or penitents, who are determined by long suffering to atone for past crimes; and who, if they could not get into the police, would probably go long pilgrimages on all fours, or with unboiled peas in their shoes.1139

He who can suppose that men so inadequately paid, who have no promotion to look forward to, and feel no security in their tenure of office, and consequently no hope of a provision for old age, will be zealous and honest in the discharge of their duties, must be very imperfectly acquainted with human nature—with the motives by which men are influenced all over the world. Indeed, no man does in reality suppose so; on the contrary, every man knows that the same motives actuate public servants in India as elsewhere. We have acted successfully upon this knowledge in all other branches of the public service, and shall, I trust, at no distant period act upon the same in that of the police; and then, and not till then, can it prove to the people what we must all wish it to be, a blessing.

The European magistrate of a district has, perhaps, a million of people to look after.1140 The native officers next under him are the Thānadārs of the different subdivisions of the district, containing each many towns and villages, with a population of perhaps one hundred thousand people. These officers have no grade to look forward to, and get a salary of twenty-five rupees a month each.1141

They cannot possibly do their duties unless they keep each a couple of horses or ponies, with servants to attend to them; indeed, they are told so by every magistrate who cares about the peace of his district. The people, seeing how much we expect from the Thānadār, and how little we give him, submit to his demands for contribution without a murmur, and consider almost any demand venial from a man so employed and paid. They are confounded at our inconsistency, and say, where they dare to speak their minds, 'We see you giving high salaries and high prospects of advancement to men who have nothing on earth to do but to collect your revenues and to decide our disputes about pounds, shillings, and pence, which we used to decide much better among ourselves when we had no other court but that of our elders to appeal to; while those who are to protect life and property, to keep peace over the land, and enable the industrious to work in security, maintain their families and pay the government revenue, are left without any prospect of rising, and almost without any pay at all.'

There is really nothing in our rule in India which strikes the people so much as this glaring inconsistency, the evil effects of which are so great and so manifest. The only way to remedy the evil is to give the police what the other branches of the public service already enjoy—a feeling of security in the tenure of office, a higher rate of salary, and, above all, a gradation of rank which shall afford a prospect of rising to those who discharge their duties ably and honestly. For this purpose all that is required is the interposition of an officer between the Thānadār and the magistrate, in the same way as the Sadr Amīn is now interposed between the Munsif and the Judge.1142 On an average there are, perhaps, twelve Thānas, or police subdivisions, in each district, and one such officer to every four Thānas would be sufficient for all purposes. The Governor-General who shall confer this boon on the people of India will assuredly be hailed as one of their greatest benefactors.1143 I should, I believe, speak within bounds when I say that the Thānadārs throughout the country give at present more than all the money which they receive in avowed salaries from government as a share of indirect perquisites to the native officers of the magistrate's court, who have to send their reports to them, and communicate their orders, and prepare the cases of the prisoners they may send in for commitment to the Sessions courts.1144 The intermediate officers here proposed would obviate all this; they would be to the magistrate at once the tapis of Prince Husain and the telescope of Prince Ali—media that would enable them to be everywhere and see everything.

I may here seem to be 'travelling beyond the record', but it is not so. In treating on the spirit of military discipline in our native army I advocate, as much as in me lies, the great general principle upon which rests, I think, not only our power in India, but what is more, the justification of that power. It is our wish, as it is our interest, to give to the Hindoos and Muhammadans a liberal share in all the duties of administration, in all offices, civil and military, and to show the people in general the incalculable advantages of a strong and settled government, which can secure life, property, and character, and the free enjoyment of all their blessings throughout the land; and give to those who perform duties as public servants ably and honestly a sure prospect of rising by gradation, a feeling of security in their tenure of office, a liberal salary while they serve, and a respectable provision for old age.

It is by a steady adherence to these principles that the Indian Civil Service has been raised to its present high character for integrity and ability; and the native army made what it really is, faithful and devoted to its rulers, and ready to serve them in any quarter of the world.1145 I deprecate any innovation upon these principles in the branches of the public service to which they have already been applied with such eminent success; and I advocate their extension to all other branches as the surest means of making them what they ought and what we must all most fervently wish them to be.

The native officers of our judicial and revenue establishments, or of our native army, are everywhere a bond of union between the governing and the governed.1146 Discharging everywhere honestly and ably their duties to their employers, they tend everywhere to secure to them the respect and affection of the people. His Highness Muhammad S'aīd Khān, the reigning Nawāb of Rāmpur, still talks with pride of the days when he was one of our Deputy Collectors in the adjoining district of Badāon, and of the useful knowledge he acquired in that office.1147 He has still one brother a Sadr Amīn in the district of Mainpurī, and another a Deputy Collector in the Hamīrpur District; and neither would resign his situation under the Honourable Company to take office in Rāmpur at three times the rate of salary, when invited to do so on the accession of the eldest brother to the 'masnad'. What they now enjoy they owe to their own industry and integrity; and they are proud to serve a government which supplies them with so many motives for honest exertion, and leaves them nothing to fear, as long as they exert themselves honestly. To be in a situation which it is generally understood that none but honest and able men can fill1148 is of itself a source of pride, and the sons of native princes and men of rank, both Hindoo and Muhammadan, everywhere prefer taking office in our judicial and revenue establishments to serving under native rulers, where everything depends entirely upon the favour or frown of men in power, and ability, industry, and integrity can secure nothing.1149