Полная версия

Полная версияПолная версия:

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 14, No. 400, November 21, 1829

It furnishes a subject of serious consideration, as well as an argument for a special providence, to know, that the accurate Reaumur, and other naturalists, have observed, that when any kind of insect has increased inordinately, their natural enemies have increased in the same proportion, and thus preserved the balance.—Ibid.

GnatsThere are few insects with whose form we are better acquainted than that of the gnat. It is to be found in all latitudes and climates; as prolific in the Polar as in the Equatorial regions. In 1736 they were so numerous, and were seen to rise in such clouds from Salisbury cathedral, that they looked like columns of smoke, and frightened the people, who thought the building was on fire. In 1766, they appeared at Oxford, in the form of a thick black cloud; six columns were observed to ascend the height of fifty or sixty feet. Their bite was attended with alarming inflammation. To some appearances of this kind our great poet, Spenser, alludes, in the following beautiful simile:—

As when a swarm of gnats at eventide,Out of the fennes of Allan doe arise,Their murmurring small trumpets sownden wide,Whiles in the air their clust'ring army flies.That as a cloud doth seem to dim the skies:Ne man nor beast may rest or take repast,For their sharp wounds and noyous injuries,Till the fierce northern wind, with blustering blast,Doth blow them quite away, and in the ocean cast.In Lapland, their numbers have been compared to a flight of snow when the flakes fall thickest, and the minor evil of being nearly suffocated by smoke is endured to get rid of these little pests. Captain Stedman says, that he and his soldiers were so tormented by gnats in America, that they were obliged to dig holes in the ground with their bayonets, and thrust their heads into them for protection and sleep. Humboldt states, that "between the little harbour of Higuerote and the mouth of the Rio-Unare, the wretched inhabitants are accustomed to stretch themselves on the ground, and pass the night buried in the sand three or four inches deep, exposing only the head, which they cover with a handkerchief."

After enumerating these and other examples of the achievements of the gnat and musquito tribe, Kirby says, "It is not therefore incredible that Sapor, King of Persia, should have been compelled to raise the siege of Nisibis by a plague of gnats, which attacked his elephants and beasts of burden, and so caused the rout of his army; nor that the inhabitants of various cities should, by an extraordinary multiplication of this plague, have been compelled to desert them; nor that, by their power of doing mischief, like other conquerors who have been the torment of the human race, they should have attained to fame, and have given their name to bays, town, and territories." Ibid.

Leaf CaterpillarsThe design of the caterpillars in rolling up the leaves is not only to conceal themselves from birds and predatory insects, but also to protect themselves from the cuckoo-flies, which lie in wait in every quarter to deposit their eggs in their bodies, that their progeny may devour them. Their mode of concealment, however, though it appear to be cunningly contrived and skilfully executed, is not always successful, their enemies often discovering their hiding place. We happened to see a remarkable instance of this last summer (1828), in a case of one of the lilac caterpillars which had changed into a chrysalis within the closely folded leaf. A small cuckoo-fly, aware, it should seem, of the very spot where the chrysalis lay within the leaf, was seen boring through it with her ovipositor, and introducing her eggs through the punctures thus made into the body of the dormant insect. We allowed her to lay all her eggs, about six in number, and then put the leaf under an inverted glass. In a few days the eggs of the cuckoo-fly were hatched, the grubs devoured the lilac chrysalis, and finally changed into pupae in a case of yellow silk, and into perfect insects like their parent.—Library of Entertaining Knowledge.

The last extract, and all in the Library of Entertaining Knowledge signed J.R. are written by Mr. J. Rennie, whose initials must be familiar to every reader as attached to some of the most interesting papers in Mr. Loudon's Magazines. He is a nice observer of Nature, and one of the most popular writers on her phenomena.

As we treated the cuts of the last portion of the "Library of Entertaining Knowledge," rather critically, we are happy to say that the engravings of insects in the present part make ample amends for all former imperfections in that branch of the work; some of the pupae, insects, their nests, &c. are admirably executed, and their selection is equally judicious and attractive.

SPIRITUOUS LIQUORS

Spirit-drinking appears to have attained a pretty considerable pitch in America, where, according to the proceedings of the American Temperance Society, half as many tuns of domestic spirits are annually produced as of wheat and flour; and in the state of New York, in the year 1825, there were 2,264 grist-mills, and 1,129 distilleries of whiskey. In a communication to this society from Philadelphia, it is calculated, that out of 4,151 deaths in that city in the year 1825, 335 are attributed solely to the abuse of ardent spirits!

WOOD ENGRAVING

In early life Bewick cut a vignette for the Newcastle newspaper, from which it is calculated that more than nine hundred thousand impressions have been worked off; yet the block is still in use, and not perceptibly impaired.

AUSTRIA

The present Emperor of Austria is a gentle, fatherly old man. We have heard none of his subjects speak of him with anything but love and affection. The meanest peasant has access to him; and, except on public occasions, he leads a simpler life than any nobleman among ourselves. It is, perhaps, less the emperor than the nobility who govern in Austria, and less the nobility than Metternich, the prince-pattern of prime-ministers.—Foreign Review.

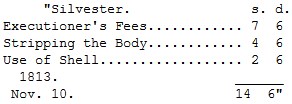

HANGING

The following letter tends to rectify an error which very generally prevails, namely, that it costs only thirteen-pence halfpenny to be hung. It is copied literatim et verbatim, from one made out by Mr. Ketch himself, and proves that a man cannot be hung for so mere a trifle:—

SCOTTISH POETRY

The passion of the Scots, from whatever race derived, for poetry and music, developed itself in the earliest stages of their history. They possessed a wild imagination, a dark and gloomy mythology; they peopled the caves, the woods, the rivers, and the mountains, with spirits, elves, giants, and dragons; and are we to wonder that the Scots, a nation in whose veins the blood of all those remote races is unquestionably mingled, should, at a very remote period, have evinced an enthusiastic admiration for song and poetry; that the harper was to be found amongst the officers who composed the personal state of the sovereign, and that the country maintained a privileged race of wandering minstrels, who eagerly seized on the prevailing superstitions and romantic legends, and wove them in rude, but sometimes very expressive versification, into their stories and ballads; who were welcome guests at the gate of every feudal castle, and fondly beloved by the great body of the people.—Tytler's History of Scotland.

TO CONSTANTINOPLE,

On approaching the city about sun-rise, from the Sea of Marmora.

A glorious form thy shining city wore,'Mid cypress thickets of perennial green,With minaret and golden dome between,While thy sea softly kiss'd its grassy shore.Darting across whose blue expanse was seenOf sculptured barques and galleys many a score;Whence noise was none save that of plashing oar;Nor word was spoke, to break the calm serene.Unhear'd is whisker'd boatman's hail or joke;Who, mute as Sinbad's man of copper, rows,And only intermits the sturdy strokeWhen fearless gull too nigh his pinnace goes.I, hardly conscious if I dream'd or woke,Mark'd that strange piece of action and repose.BERWICK

In the thirteenth century Berwick enjoyed a prosperity, such as threw every other Scottish port into the shade; the customs of this town, at the above date, amounted to about one-fourth of all the customs of England.

SPIRIT OF THE PUBLIC JOURNALS

THE LORD MAYORS DAY

"Spirit of Momus! thou'rt wandering wide.When I would thou wert merrily perch'd by my side,For I am sorely beset by the blues;Thou fugitive elf! I adjure thee return,By Fielding's best wig, and the ashes of Sterne,Appear at the call of my muse."It comes, with a laugh on its rubicund face;Methinks, by the way, it's in pretty good case,For a spirit unblest with a body;"On the claret bee's-wing," says the sprite, "I regale;But I'm ready for all—from Lafitte down to ale,From Champagne to a tumbler of toddy."Then I'm not over-nice, as at least you must know,In the rank of my hosts—for the lofty or lowAre alike to the Spirit of Mirth;I care not a straw with whom I have dined,Though a family dinner's not much to my mind,And a proser's a plague upon earth."But where, my dear sprite, for this age have you been?Have you plunged in the Danube, or danced on the Seine?Or have taken in Lisbon your station?Or have flapped over Windsor your butterfly-wings,O'er its bevy of beauties, and courtiers, and kings—The wonders and wits of the nation?""No; of all climes for folly, Old England's the clime;Of all times for fully, the present's the time;And my game is so plentiful here,That all months are the same, from December to May;I can bag in a minute enough for a day—In a day, bag enough for a year."My game-bag has nooks for 'Notes, Sketches, and Journeys,'By soldiers and sailors, divines and attorneys,Through landscapes gay, blooming, and briary;And so, as you seem rather pensive to-night,To dispel your blue-devils, I'll briefly reciteA specimen-leaf from my diary:—"'THE NINTH OF NOVEMBER"'Through smoke-clouds as dark as a forest of rooks,The rich contribution of blacksmiths and cooksFrom the huge human oven below,I heard old St. Paul's gaily pealing away;Thinks I to myself, 'It is Lord Mayor's Day,So, I'll go down and look at the Show.'"'I spread out my pinions, and sprang on my perch—'Twas the dragon on Bow, that odd sign of the church,The episcopal centre of action;All Cheapside was crowded with black, brown, and fair,Like a harlequin's jacket, or French rocquelaire,A legitimate Cheapside attraction.Then rung through the tumult a trumpet so shrill,That it frightened the ladies all down Ludgate Hill,And the owlets in Ivy Lane;Then came in their chariots, each face in full blow,The sheriffs and aldermen, solemn and slow,All bombazine, bag-wig and chain."'Then came the old tumbril-shaped city machine,With a Lord Mayor so fat that he made the coach lean;Lord Waithman was scarcely a brighter man;The wits said the old groaning wagon of state,Which for ages had carried Lord Mayors of such weight,To-day would break down with a lighter man."'Then proud as a prince, at the head of the bandRode the city field-marshal, with truncheon in hand,Though his epaulettes lately are gone;But he's still fine enough to astonish the cits,And drive the economists out of their wits,From Lords Waithman and Wood, to Lord John."'But I now left the pageant—wits, worthies, and all—And flew through the smoke to the roof of Guildhall,And perched on the grand chandelier;The dinner was stately, the tables were full—There sat, multiplied by three thousand, John Bull,Resolved to make all disappear."'And then came the speeches; Lord Hunter was fine—Lord Wood, finer still—Lord Thompson, divine,The sheriffs were Ciceros a-piece;Lord Crowther was sick, though he managed to eatWhat, if races were feasts, would have won him the plate;But he tossed off a bumper to Greece."'Then all was enchantment—all hubbub and smiles—The wit of Old Jewry, the grace of St. Giles,The force of the Billingsgate tongue:Till the eloquent Lord Mayor demanding 'Who malts?'—The understood sign for beginning the waltz—In a fright through the ceiling I sprung.'"Monthly Magazine

AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF A LANDAULET

(Concluded from page 302.)It happened to be a dull time of year, and for some months my wheels ceased to be rotatory: I got cold and damp; and the moths found their way to my inside: one or two persons who came to inspect me declined becoming purchasers, and peering closely at my panels, said something about "old scratch." This hurt my feelings, for if my former possessor was not quite so good as she might have been, it was no fault of mine.

At length, after a tedious inactivity, I was bought cheap by a young physician, who having rashly left his provincial patients to set up in London, took it into his head that nothing could be done there by a medical man who did not go upon wheels; he therefore hired a house in a good situation, and then set me up, and bid my vendor put me down in his bill.

It is quite astonishing how we flew about the streets and squares, acting great practice; those who knew us by sight must have thought we had a great deal to do, but we practised nothing but locomotion. Some medical men thin the population, (so says Slander,) my master thinned nothing but his horses. They were the only good jobs that came in his way, and certainly he made the most of them. He was obliged to feed them, but he was very rarely feed himself. It so happened that nobody consulted us, and the unavoidable consumption of the family infected my master's pocket, and his little resources were in a rapid decline.

Still he kept a good heart; indeed, in one respect, he resembled a worm displayed in a bottle in a quack's shop window—he was never out of spirits! He was deeply in debt, and his name was on every body's books, always excepting the memorandum-books of those who wanted physicians. Still I was daily turned out, and though nobody called him in, he was to be seen, sitting very forward, apparently looking over notes supposed to have been taken after numerous critical cases and eventful consultations. Our own case was hopeless, our progress was arrested, an execution was in the house, servants met with their deserts and were turned off, goods were seized, my master was knocked up, and I was knocked down for one hundred and twenty pounds.

Again my beauties blushed for a while unseen; but I was new painted, and, like some other painted personages, looked, at a distance, almost as good as new. Fortunately for me, an elderly country curate, just at this period, was presented with a living, and the new incumbent thought it incumbent upon him to present his fat lady and his thin daughter with a leathern convenience. My life was now a rural one, and for ten long years nothing worth recording happened to me. Slowly and surely did I creep along green lanes, carried the respectable trio to snug, early, neighbourly dinners, and was always under lock and key before twelve o'clock. It must be owned I began to have rather an old-fashioned look; my body was ridiculously small, and the rector's thin daughter, the bodkin, or rather packing-needle of the party, sat more forward, and on a smaller space than bodkins do now-a-days. I was perched up three feet higher than more modern vehicles, and my two lamps began to look like little dark lanterns. But my obsoleteness rendered me only more suited to the service in which I was enlisted. Honest Roger, the red-haired coachman, would have looked like a clown in a pantomime, in front of a fashionable equipage; and Simon the footboy, who slouched at my back, would have been mistaken for an idle urchin surreptitiously enjoying a ride. But on my unsophisticated dickey and footboard no one could doubt but that Roger and Simon were in their proper places. The rector died; of course he had nothing more to do with the living, it passed into other hands; and a clerical income being (alas, that it should be so!) no inheritance, his relict suddenly plunged in widowhood and poverty, had the aggravated misery of mourning for a deaf husband, while she was conscious that the luxuries and almost the necessaries of life were for ever snatched from herself and her child.

Again I found myself in London, but my beauty was gone, I had lost the activity of youth, and when slowly I chanced to creak through Long Acre, Houlditch, my very parent, who was standing at his door sending forth a new-born Britska, glanced at me scornfully, and knew me not! I passed on heavily—I thought of former days of triumph, and there was madness in the thought I became a crazy vehicle! straw was thrust into my inward parts, I was numbered among the fallen,—yes, I was now a hackney-chariot, and my number was one hundred!

What tongue can tell the degradations I have endured! The persons who familiarly have called me, the wretches who have sat in me—never can this be told. Daily I take my stand in the same vile street, and nightly am I driven to the minor theatres—to oyster-shops—to desperation!

One day, when empty and unoccupied, I was hailed by two police-officers who were bearing between them a prisoner. It was the seducer of my second ill-fated mistress; a first crime had done its usual work, it had prepared the mind for a second, and a worse: the seducer had done a deed of deeper guilt, and I bore him one stage towards the gallows. Many months after, a female called me at midnight: she was decked in tattered finery, and what with fatigue and recent indulgence in strong liquors, she was scarcely sensible, but she possessed dim traces of past beauty. I can say nothing more of her, but that it was the fugitive wife whom I had borne to Brighton so many years ago. No words of mine could paint the living warning that I beheld. What had been the sorrows of unmerited desertion and unkindness supported by conscious rectitude, compared with the degraded guilt, the hopeless anguish, that I then saw?

I regret to say, I was last month nigh committing manslaughter; I broke down in the Strand and dislocated the shoulder of a rich old maid. I cannot help thinking that she deserved the visitation, for, as she stepped into me in Oxford Street, she exclaimed, loud enough to be heard by all neighbouring pedestrians, "Dear me! how dirty! I never was in a hackney conveyance before!"—though I well remembered having been favoured with her company very often. A medical gentleman happened to be passing at the moment of our fall; it was my old medical master. He set the shoulder, and so skilfully did he manage his patient, that he is about to be married to the rich invalid, who will shoulder him into prosperity at last.

I last night was the bearer of a real party of pleasure to Astley's:—a bride and bridegroom, with the mother of the bride. It was the widow of the old rector, whose thin daughter (by the by she is fattening fast) has had the luck to marry the only son of a merchant well to do in the world.

The voice suddenly ceased!—I awoke—the door was opened, the steps let down—I paid the coachman double the amount of his fare, and in future, whenever I stand in need of a jarvey, I shall certainly make a point of calling for number One Hundred.

THE GATHERER

"A snapper-up of unconsidered trifles."SHAKSPEARE.BELL.—THE CRY OF THE DEER SO CALLED

I am glad of an opportunity to describe the cry of the deer by another name than braying, although the latter has been sanctioned by the use of the Scottish metrical translation of the Psalms. Bell seems to be an abbreviation of the word bellow. This sylvan sound conveyed great delight to our ancestors chiefly, I suppose, from association. A gentle knight in the reign of Henry VIII., Sir Thomas Wortley, built Wantley Lodge, Warncliffe Forest, for the purpose, as the ancient inscription testifies, of "Listening to the Harts' Bell."

C.K.W.THE CURSE OF SCOTLAND

The origin of the nine of diamonds being called the Curse of Scotland is not generally known. It arose from the following circumstance:—The night before the battle of Culloden, the Duke of Cumberland thought proper to send orders to General Campbell not to give quarter; and this order being despatched in much haste, was written on a card. This card happened to be the nine of diamonds, from which circumstance it got the appellation above named.

W.M.POLITICAL PUNS

Among the many expedients resorted to by the depressed party in a state to indulge their sentiments safely, and probably at the same time, according to situation, to sound those of their companions, puns and other quibbles have been of notable service. The following is worthy of notice:—The cavaliers during Cromwell's usurpation, usually put a crumb of bread into a glass of wine, and before they drank it, would exclaim with cautious ambiguity, "God send this Crum well down!" A royalist divine also, during the Protectorate, did not scruple to quibble in the following prayer, which he was accustomed to deliver:—"O Lord, who hast put a sword into the hand of thy servant, Oliver, put it into his heart ALSO—to do according to thy word." He would drop his voice at the word also, and, after a significant pause, repeat the concluding sentence in an under tone.

W.M. Erratum at page 306.—For Hemiptetera read HEMIPTERAANNUALS FOR 1830

With No. 398 was published a SUPPLEMENT, containing the first portion of the SPIRIT OF THE ANNUALS, with a splendid Engraving of the CITY OF VERONA, and Notices of the Gem, Literary Souvenir, Friendship's Offering, and Amulet.

Printed and Published by J. LIMBIRD 143, Strand, (near Somerset House,) London; sold by ERNEST FLEISCHER, 626, New Market, Leipsic; and by all Newsmen and Booksellers.

1

See "Portuguese Prisons," MIRROR, vol. xii, p. 99.

2

A fact.

3

For the loan of which we thank our esteemed correspondent, P.T.W.

4

It need hardly be explained that the above is a section, or only one half of the dial.

5

For a notice of the application of this cement to useful purposes, see No. 396, page 283.—ED. MIRROR.