Полная версия

Полная версияПолная версия:

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 14, No. 400, November 21, 1829

She was peculiarly sensitive to music. There was one song (it was Moore's Farewell to his Harp) to which she "took a special fancy;" she wished to hear it only at twilight—thus, with that same perilous love of excitement which made her place the windharp in the window when she was composing, seeking to increase the effect which the song produced upon a nervous system, already diseasedly susceptible; for it is said, that whenever she heard this song she became cold, pale, and almost fainting; yet it was her favourite of all songs, and gave occasion to these verses, addressed, in her fifteenth year, to her sister.

When evening spreads her shades around,And darkness fills the arch of heaven;When not a murmur, not a soundTo Fancy's sportive ear is given;When the broad orb of heaven is bright,And looks around with golden eye;When Nature, softened by her light.Seems calmly, solemnly to lie;Then, when our thoughts are raised aboveThis world, and all this world can give,Oh, Sister! sing the song I love,And tears of gratitude receive.The song which thrills my bosom's core,And, hovering, trembles half afraid,Oh, Sister! sing the song once more,Which ne'er for mortal ear was made.'Twere almost sacrilege to singThose notes amid the glare of day;Notes borne by angels' purest wing,And wafted by their breath away.When, sleeping in my grass-grown bed,Shouldst thou still linger here above,Wilt thou not kneel beside my head,And, Sister! sing the song I love?To young readers it might be useful to observe, that these verses in one place approach the verge of meaning, but are on the wrong side of the line: to none can it be necessary to say, that they breathe the deep feeling of a mind essentially poetical.

"Her desire of knowledge increased as she grew more capable of appreciating its worth;" and she appreciated much beyond its real worth the advantages which girls derive from the ordinary course of female education. "Oh!" she said one day to her mother, "that I only possessed half the means of improvement which I see others slighting! I should be the happiest of the happy." A youth whom nature has endowed with diligence and a studious disposition has, indeed, too much reason to regret the want of that classical education which is wasted upon the far greater number of those on whom it is bestowed; but, for a girl who displays a promise of genius like Lucretia, and who has at hand the Bible and the best poets in her own language, no other assistance can be needed in her progress than a supply of such books as may store her mind with knowledge. Lucretia's desire of knowledge was a passion which possessed her like a disease. "I am now sixteen years old," she said, "and what do I know? Nothing!—nothing, compared with what I have yet to learn. Time is rapidly passing by: that time usually allotted to the improvement of youth; and how dark are my prospects in regard to this favourite wish of my heart!" At another time she said—"How much there is yet to learn!—If I could only grasp it at once!"

In October 1824, when she had just entered upon her seventeenth year, a gentleman, then on a visit at Plattsburgh, saw some of her verses—was made acquainted with her ardent desire for education, and with the circumstances in which she was placed; and he immediately resolved to afford her every advantage which the best schools in the country could furnish. This gentleman has probably chosen to have his name withheld, being more willing to act benevolently than to have his good deeds blazoned; and yet, stranger as he needs must be, there are many English readers to whom it would have been gratifying, could they have given to such a person "a local habitation and a name." When Lucretia was made acquainted with his intention, the joy was almost greater than she could bear. As soon as preparations could be made, she left home, and was placed at the "Troy Female Seminary," under the instruction of Mrs. Willard. There she had all the advantages for which she had hungered and thirsted; and, like one who had long hungered and thirsted, she devoured them with fatal eagerness. Her application was incessant; and its effects on her constitution, already somewhat debilitated by previous disease, became apparent in increased nervous sensibility. Her letters at this time exhibit the two extremes of feeling in a marked degree. They abound in the most sprightly or most gloomy speculations, bright hopes and lively fancies, or despairing fears and gloomy forebodings. In one of her letters from this seminary, she writes thus to her mother: "I hope you will feel no uneasiness as to my health or happiness; for, save the thoughts of my dear mother and her lonely life, and the idea that my dear father is slaving himself, and wearing out his very life, to earn a subsistence for his family—save these thoughts (and I can assure you, mother, they come not seldom), I am happy. Oh! how often I think, if I could have but one-half the means I now expend, and be at liberty to divide that with mamma, how happy I should be!—cheer up and keep good courage." In another, she says: "Oh! I am so happy, so contented now, that every unusual movement startles me. I am constantly afraid that something will happen to mar it." Again, she says: "I hope the expectations of my friends will not be disappointed: but I am afraid you all calculate upon too much. I hope not, for I am not capable of much. I can study and be industrious; but I fear I shall not equal the hopes which you say are raised." The story of Kirke White should operate not more as an example than a warning; but the example is followed and the warning overlooked. Stimulants are administered to minds which are already in a state of feverish excitement. Hotbeds and glasses are used for plants which can only acquire strength in the shade; and they are drenched with instruction, which ought "to drop as the rain, and distil as the dew—as the small rain upon the tender herb, and as the shower upon the grass."

During the vacation, in which she returned home, she had a serious illness, which left her feeble and more sensitive than ever. On her recovery she was placed at the school of Miss Gilbert, in Albany; and there, in a short time, a more alarming illness brought her to the very borders of the grave. Before she entered upon her intemperate course of application at Troy, her verses show that she felt a want of joyous and healthy feeling—a sense of decay. Thus she wrote to a friend, who had not seen her since her childhood:—

And thou hast mark'd in childhood's hourThe fearless boundings of my breast,When fresh as summer's opening flower,I freely frolick'd and was blest.Oh say, was not this eye more bright?Were not these lips more wont to smile?Methinks that then my heart was light,And I a fearless, joyous childAnd thou didst mark me gay and wild,My careless, reckless laugh of mirth:The simple pleasures of a child,The holiday of man on earth.Then thou hast seen me in that hour,When every nerve of life was new,When pleasures fann'd youth's infant flower,And Hope her witcheries round it threw.That hour is fading; it has fled;And I am left in darkness now,A wanderer tow'rds a lowly bed,The grave, that home of all below.Young poets often affect a melancholy strain, and none more frequently put on a sad and sentimental mood in verse than those who are as happy as an utter want of feeling for any body but themselves can make them. But in these verses the feeling was sincere and ominous. Miss Davidson recovered from her illness at Albany so far only as to be able to perform the journey back to Plattsburgh, under her poor mother's care. "The hectic flush of her cheek told but too plainly that a fatal disease had fastened upon her constitution, and must ere long inevitably triumph." She however dreaded something worse than death, and while confined to her bed, wrote these unfinished lines, the last that were ever traced by her indefatigable hand, expressing her fear of madness.

There is a something which I dread,It is a dark, a fearful thing;It steals along with withering tread.Or sweeps on wild destruction's wing.That thought comes o'er me in the hour,Of grief, of sickness, or of sadness;'Tis not the dread of death,—'tis more,It is the dread of madness.Oh, may these throbbing pulses pauseForgetful of their feverish course;May this hot brain, which burning, glows,With all a fiery whirlpool's force,Be cold, and motionless, and stillA tenant of its lowly bed;But let not dark delirium steal—The stanzas with which Kirke White's fragment of the "Christiad" concludes, are not so painful as these lines. Had this however been more than a transient feeling, it would have produced the calamity which it dreaded: it is likely, indeed, that her early death was a dispensation of mercy, and saved her from the severest of all earthly inflictions; and that same merciful Providence which removed her to a better state of existence, made these apprehensions give way to a hope and expectation of recovery, which, vain as it was, cheered some of her last hours. When she was forbidden to read it was a pleasure to her to handle the books which composed her little library, and which she loved so dearly. "She frequently took them up and kissed them; and at length requested them to be placed at the foot of her bed, where she might constantly see them," and anticipating a revival which was not to be, of the delight she should feel in reperusing them, she said often to her mother, "what a feast I shall have by-and-bye." How these words must have gone to that poor mother's heart, they only can understand who have heard such like anticipations of recovery from a dear child, and not been able, even whilst hoping against hope, to partake them.

When sensible at length of her approaching dissolution, she looked forward to it without alarm; not alone in that peaceful state of mind which is the proper reward of innocence, but in reliance on the divine promises, and in hope of salvation through the merits of our blessed Lord and Saviour. The last name which she pronounced was that of the gentleman whose bounty she had experienced, and towards whom she always felt the utmost gratitude. Gradually sinking under her malady, she passed away on the 27th of August, 1825, before she had completed her seventeenth year. Her person was singularly beautiful; she had "a high, open forehead, a soft, black eye, perfect symmetry of features, a fair complexion, and luxuriant dark hair. The prevailing expression of her face was melancholy. Although, because of her beauty as well as of her mental endowments, she was the object of much admiration and attention, yet she shunned observation, and often sought relief from the pain it seemed to inflict upon her, by retiring from the company."

That she should have written so voluminously as has been ascertained, (says the editor of her Poems), is almost incredible. Her poetical writings which have been collected, amount in all to two hundred and seventy-eight pieces of various length; when it is considered that among these are at least five regular poems of several cantos each, some estimate may be formed of her poetical labours. Besides there were twenty-four school exercises, three unfinished romances, a complete tragedy, written at thirteen years of age, and about forty letters, in a few months, to her mother alone. To this statement should also be appended the fact, that a great portion of her writings she destroyed. Her mother observes, "I think I am justified in saying that she destroyed at least one-third of all she wrote."

Of the literary character of her writings, (says the editor), it does not, perhaps, become me largely to speak; yet I must hazard the remark, that her defects will be perceived to be those of youth and inexperience, while in invention, and in that mysterious power of exciting deep interest, of enchaining the attention and keeping it alive to the end of the story; in that adaptation of the measure to the sentiment, and in the sudden change of measure to suit a sudden change of sentiment; a wild and romantic description; and in the congruity of the accompaniment to her characters, all conceived with great purity and delicacy—she will be allowed to have discovered uncommon maturity of mind, and her friends to have been warranted in forming very high expectations of her future distinction.

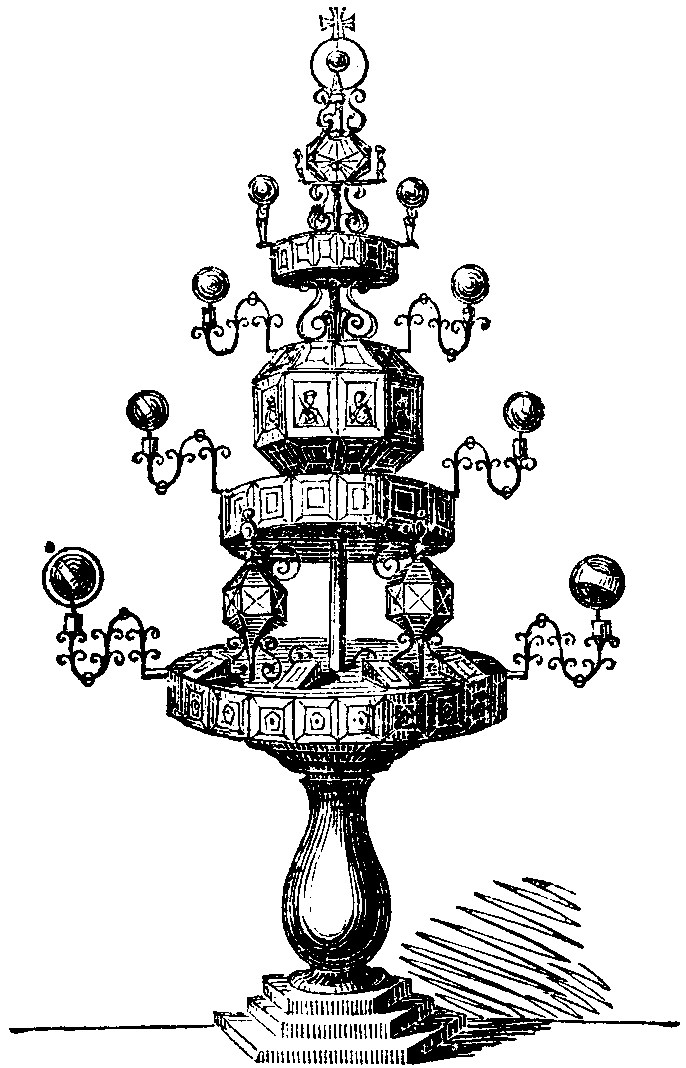

Curious Dial

This Dial, which was really no common or vulgar invention, formerly stood in Privy Garden, Whitehall, at a short distance from Gibbons's noble brass statue of James II., which, as a waggish friend of ours said of the horse at Charing Cross, remains in statu-quo to this day. The Dial was invented by one Francis Hall, alias Line, a Jesuit, and Professor of Mathematics at Liege, in Germany. It was set up, as the old books have it, in the year 1669, by order of Charles II.; and in addition to the parts represented in the cut, the inventer intended to place a water-dial at each corner, which he had nearly completed when the original Dial for want of a cover, as he quaintly observes, (which according to his Majestie's Gracious Order should have been set over it in the Winter) was much injured by the snow lying frozen upon it. But there was no chance of obtaining this out of Charles's coffers, and the Dial soon became useless. Its explanation was, however, considered by many mathematical men of the period as too valuable to be lost, and the Professor accordingly printed the description at Liege, in 1673, in which were plates and diagrams of the several parts. The matter was too grave for pleasant, anecdotical Pennant, who, speaking of the Dial, in his London, says "the description surpasses my powers:" he refers the reader to the above work, a "very scarce book" in his time, and we have been at some pains to obtain the reprint, (London, 1685,) appended to Holwell's Clavis Horologiae; or Key to the whole art of Arithmetical Dialling, small 4to. 1712.3

The whole Dial stood on a stone pedestal, and consisted of six4 parts, rising in a pyramidal form, as represented in the Cut.

The base, or first piece, was a table of about 40 inches in diameter, and 8 or 9 inches thick, in the edge of which were 20 glazed dials, with the Jewish, Babylonian, Italian, Astronomical, and usual European methods of counting the hours: they were all vertical or declining Dials, the style or gnomon being a lion's paw, unicorn's horn, or some emblem from the royal arms. On the upper part of the Table were 8 reclining dials, glazed, and showing the hour in different ways—as by the shade of the style falling upon the hour-lines, the hour-lines falling on the style, or without any shade of hour-lines or style, &c. Upon this piece or table stood also 4 globes, cut into planes, with geographical, astronomical, and astrological dials. From the table also, east, west, north, and south, were four iron branches supporting glass bowls, showing the hour by fire, water, air, and earth.

The second piece of the pyramid was also a round table somewhat less than the first, with 4 iron supporters, and dials on the edge, showing the different rising of remarkable stars; the style to each being a little star painted upon the inside of the glass cover. From this piece also branched 4 glass bowls to show the hour by a style without a shadow, a shadow without a style, &c. Upon the upper part of the table were 8 reclining planes, 4 covered with looking-glass, on which the hour-lines, or style of a dial being painted, were reflected upon the bottom inclining planes of the third piece, and there showed the hour. The other 4 had also dials upon them, which were to be seen in a looking-glass placed upon the bottom of the third piece.

The third piece was a large hollow globe, about 24 inches in diameter, and cut into 26 planes, two of which served for top and bottom. The rest were divided into 8 equal reclining planes, 8 equal inclining planes, and 8 equal vertical or upright planes; all of which were hollow. The incliners were not covered with glass, but left open, so as better to receive and show the dials reflected from the second piece. Two of the 8 upright planes towards the north had no bottoms, but were covered only with clear glass, or windows to look into the globe, and thus see the dials as well within as without the same. The other 6 had not only each a cover of clear polished glass, with a dial described on them, like those of the first piece, but had a glass for their bottom; which glass was thinly painted over white, so that the shade of the hour-lines drawn upon the cover, might be seen as well within as without the globe. On these bottom glasses were painted portraits, each holding a sceptre, or truncheon, the end of which pointed to the hour. Two also of the recliners towards the north, had only a glass cover, or window to look into the globe: the other 6 had double glass like the former; their dials being some upon the cover, others upon the bottom; but all so contrived, that the hour could only be known by them, by looking within the globe. From the top of this globe issued 4 iron branches with glass bowls with dials showing the time according to the several ways of counting the hours. These bowls were painted inside so as to keep out the light, except a point left like a star, through which the sun-beams showed the hour; and the place where the hour-lines were drawn, was only painted on the outside thinly with white colour, so that the sun-light passing through the star might be seen, and show the hour.

The fourth piece stood on the globe, had 4 iron supporters, and was a table about 20 inches in diameter, and 6 in thickness! The edge was cut into 12 concave superficies like so many half-cylinders; on each of which was a dial showing the hour by the shade of a fleur-de-lis fixed at the top of each half-cylinder. From the top of this table issued 4 iron branches, with glass bowls, like those of the first, second, and third pieces, though proportionally less. The dials on these bowls showed only the usual hour, and otherwise differed from the third piece; here the hour-lines being left clear for the sunbeams to pass through, that by so passing, they might exhibit the same dial on the opposite side of the bowl, which was thinly painted white, that the said hours might be seen, and show the hour by their passing over a little star painted in the middle.

The fifth piece likewise upon 4 iron supporters, was a globe of about 12 inches diameter, cut into 14 planes, viz. 8 triangles, equal and equilateral; and the other 6 were equal squares. The dials on these planes showed the usual hour by the shade of a fleur-de-lis fastened to the top or bottom of each plane.

The last, or top piece of the pyramid, was a glass bowl of 7 inches diameter, upon a foot of iron. The north side of this piece was thinly painted over white, that the shade of a little golden ball, placed in the middle of the bowl, might be seen to pass over the hour-lines which were drawn upon the white colour, and noted the hour. The bowl was included between two circles of iron gilt, with a cross on the top.

Such is a general description of the parts or divisions of this very curious Dial. To which may be added that the first four pieces had all their sides covered with little plates of black glass, first cemented to the said pieces, except those places whereon the dials were drawn; which being also covered with plates of polished glass, nearly the whole of the outside of the dial appeared to be glass; the angles or corners being elegantly gilt, as were in part the iron work of the pyramid, supporters, branches, styles, &c.

We have abridged and in part rewritten this explanation from upwards of six closely-printed 4to. pages. After the general description, in the original tract, the different sections or parts of the dial, 73 in number, are still further explained, and illustrated by 17 plates, besides a vertical section, of which last our Cut is a copy. Perhaps these details would tire the general reader, and on that account we do not press them: a few of them, however, may be noticed still further.

Of these, the Bowls appear to be the most attractive. One on the first piece, by fire was a little glass bowl filled with clear water. This bowl was about three inches diameter, placed in the middle of another sphere, about six inches diameter, consisting of several iron rings or circles, representing the hour circles in the heavens. The hour was known by applying the hand to these circles when the sun shone, when that circle where you felt the hand burnt by the sunbeams passing through the bowl filled with water, showed the true hour, according to the verse beneath it:

Cratem tange, manusq horam tibi reddet adusta.The phenomenon is thus explained by the Professor: "the parallel rays of the sun passing through the little bowl, are bent by the density of the water, into a cone or pyramid, whose vertex reaches a little beyond those hour circles, and there burns the hand applied; for so many rays being all united into a point, must needs make an intense heat, which heat is so powerful in the summer-time, that it will fire a piece of wood applied to it."

To many of the Dials were suitable inscriptions as above, and these with the references must have made the construction of the whole a task of immense labour. It would be absurd to expect that Charles II. had much to do with its completion, for he was, in his own estimation, more pleasantly employed than in watching the flight of time by heavenly luminaries. His attractions were on earth, where the splendour of a wicked court and the witchery of bright eyes eclipsed all other pursuits. Still, the licentious king was not forgotten by the inventer of the dial. Among the pictures on some of the glasses were portraits of the king, the two queens, the duke of York, prince Rupert, &c. In the king's picture, the hour was shown by the shade of the hour-lines passing over the top of the sceptre—perhaps the only time the royal trifier ever pointed to so useful an end. Prince Rupert, by his contributions to science, had a better right to be there; but Charles was not even grateful enough for the elevation to protect the precious Dial from rain and snow.

In the list of subscribers for the reprint of the Tract, occurs "Jacob Chandler, basket-maker:" in our times this would be considered a knotty work for any but a professional reader.

NOTES OF A READER

HISTORY OF INSECTS

The Family Library, No. 7Library of Entertaining Knowledge, Part 6.—Insect ArchitectureAt present we can only notice these works as two of the most delightful volumes that have for some time fallen into our hands, and as possessing all the merits which characterize the previous portions of the Series. Our cognizance of them, in a collected form, must rest till the other half appears; in the meantime a few flying extracts will prove amusing:—

Bees without a QueenThese humble creatures cherish their queen, feed her, and provide for her wants. They live only in her life, and die when she is taken away. Her absence deprives them of no organ, paralyzes no limb, yet in every case they neglect all their duties for twenty-four hours. They receive no stranger queen before the expiration of that time; and if deprived of the cherished object altogether, they refuse food, and quickly perish. What, it may be asked, is the physical cause of such devotion? What are the bonds that chain the little creature to its cell, and force it to prefer death, to the flowers and the sunshine that invite it to come forth and live? This is not a solitary instance, in which the Almighty has made virtues, apparently almost unattainable by us, natural to animals! For while man has marked, with that praise which great and rare good actions merit, those few instances in which one human being has given up his own life for another—the dog, who daily sacrifices himself for his master, has scarcely found an historian to record his common virtue.—Family Library.

Cleanliness of BeesAmong other virtues possessed by bees, cleanliness is one of the most marked; they will not suffer the least filth in their abode. It sometimes happens that an ill-advised slug or ignorant snail chooses to enter the hive, and has even the audacity to walk over the comb; the presumptuous and foul intruder is quickly killed, but its gigantic carcass is not so speedily removed. Unable to transport the corpse out of their dwelling, and fearing "the noxious smells" arising from corruption, the bees adopt an efficacious mode of protecting themselves; they embalm their offensive enemy, by covering him over with propolis; both Maraldi and Reaumur have seen this. The latter observed that a snail had entered a hive, and fixed itself to the glass side, just as it does against walls, until the rain shall invite it to thrust out its head beyond its shell. The bees, it seemed, did not like the interloper, and not being able to penetrate the shell with their sting, took a hint from the snail itself, and instead of covering it all over with propolis, the cunning economists fixed it immovably, by cementing merely the edge of the orifice of the shell to the glass with this resin, and thus it became a prisoner for life, for rain cannot dissolve this cement, as it does that which the insect itself uses.5—Ibid.