Полная версия

Полная версияПолная версия:

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 14, No. 400, November 21, 1829

Various

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction / Volume 14, No. 400, November 21, 1829

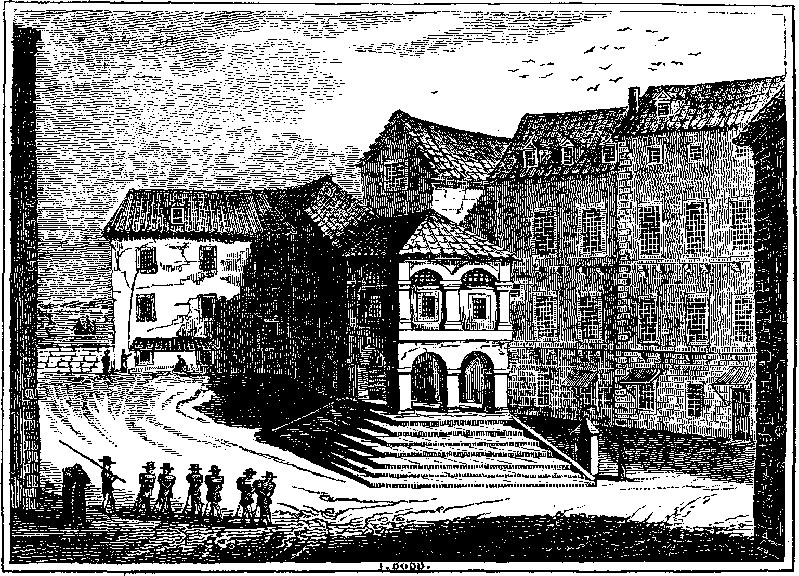

The Limoeiro, at Lisbon

Locks, bolts, and bars! what have we here?—a view of the Limoeiro, or common jail, at Lisbon, whose horrors, without the fear of Don Miguel in our hearts, we will endeavour to describe, though lightly—merely in outline,—since nothing can be more disagreeable than the filling in.

For this purpose we might quote ourselves, i.e. one of our correspondents,1 or a host of travellers and residents in the Portuguese capital; but we give preference to Mr. W. Young, who has borne much of the hard fare of the prison, and can accordingly speak more fully of its accommodations and privations. Mr. Young is an Englishman, who married a Portuguese lady in Leiria, and resided for several years in that town. He was arrested in May, 1828, on suspicion of disaffection towards Don Miguel's government: nothing appears to have been proved against him, and after having suffered much disagreeable treatment in different jails in Leiria and Lisbon, he was discharged in the following September, on condition of leaving the country. He returned to England, and lost no time in publishing a volume entitled "Portugal in 1828;" with "A Narrative of the Author's Residence there and of his persecution and confinement as a state prisoner."

The prison, says Mr. Young, stands on the highest ground in St. George's Castle, and is the first building on the south side toward the Tagus. Near the entrance it is divided internally as follows below:—Saletta (the small hall;) Salla Livre (free hall,) so called, because visiters are allowed to go in to see their friends, except when the jailer or intendant orders otherwise; Salla Fechado (the hall shut,) so called, because no communication is allowed with the prisoners in that hall; Enchovia (the common prison,) where thieves, murderers, and vagabonds of every description are confined. This last receptacle is a horrid place; and is often made use of as a punishment for prisoners from other parts of the gaol. Hither they are sent when they commit any offence, for as many days as the jailer may think proper, and are often put in irons during that time.

Besides these different prisons on the ground floor, there are eight dungeons in a line, all nearly alike in shape and size; but some are superior to others as to light and air: and in proportion to the degree they wish to annoy the unfortunate victim, so are these dungeons used. A few dollars never fail to procure a better light and air when properly applied.

Three of these dungeons are about six feet higher than the other five. There is a corridor in the front of them, which is always shut up when any one is confined in them, so that no one can ever approach the door of a dungeon. And to make this a matter of certainty, whenever the jailer or officers of the prison carry prisoners their food, they lock the door of the corridor before they open that of the dungeon.

The first of the lower five of these dungeons is in the passage leading from, the Salla Livre, and next door to the privy of the prison; so that it is never used as a secret dungeon. The lower four are enclosed as those above, and are much darker than that in the passage. This latter is claimed by the book-keeper as his property, and I hired it of him to sleep in, and to be alone when I wished to be so.

The dungeons are all bomb proof, and over them is a terrace thickly formed of brick and stone; still I could distinctly hear the sentry walking over my head when all was quiet at night.

The walls of these cells are about six feet thick, with bars inside and out; the bars in the windows are three inches square, making twelve inches in circumference, and being crossed they form squares of about eight inches; the windows differ very much in size, some not being half so large as others.

Besides these double bars, there is a shutter immensely strong and close, so that when shut, light is totally excluded; the iron door has a strong bolt and lock, and outside of this there is a strong wooden door; in the front of the windows, and about six feet from them, there is a high wall; so that in the best of these dungeons, there is only a reflected light.

These are all the prisons on the ground floor, and when full (which they too often are) the wretched prisoners are forced to lie at night in two rows, with their feet to the wall, and their heads to the middle of the room; this position they adopt on account of the cold and damp of the stone walls; they touch each other, and the floor is completely covered. Nay, at times, so full is the gaol, that they are obliged to lie on the corridors, and even on the steps.

The Saletta will hold forty prisoners, the Salla Livre more than sixty, the Salla Fechado one hundred, and the Enchovia, near one hundred and forty. When one prison becomes too full, they remove some of the victims to another, or send them to the forts, or on board the ships in the river.

The first floor is divided into two parts, officers' rooms, and the Sallao, (saloon or large hall.) This hall will hold about 150 persons, when full. Besides the Sallao and officers' rooms on the first floor, there is a room set apart for questioning people who are in the dungeons. This room has an entrance from the street, and another through a passage from the dungeons, as well as one from the officers' rooms.

The magistrate and his clerk enter from the street, and no one in the prison sees them. The prisoner is taken up stairs from the dungeon, and the jailer or book-keeper enters from the officers' apartments. Every thing is done in the most secret manner. If they cannot cause the prisoner to commit himself, by confessing to the offence with which he is charged, they send him back again to the dungeon.

The gaol of St. George's has a second floor tier of offices; but that belongs to the governor and jailer; there are no prisoners above the ground and the first floor.

None of the authorities ever inquire whether he has any means of subsistence; there is neither bed blanket, nor even straw, unless the prisoner can buy it, and then he must pay the guards to let it pass to him.

Amongst the many thousands of unfortunate beings who are now confined in Portugal, great numbers of them are without money or any other means of subsistence; and were it not for the charity of people in general, starvation would necessarily ensue.

The only authorities employed about the prison are a jailer, secretary, and eight guards; of the latter three are always on duty; one of them being stationed at the first iron gate at the entrance of the prison, another at the second gate, and a third to attend the interior, each with a bunch of keys in his hand, which serve for nearly all the doors. The guards are relieved every night at nine o'clock, when, the man who is posted at the outer door carries a strong iron rod (see the Engraving) with which he strikes every bar in the windows and gates of the gaol; and if any one of them does not vibrate, or ring, he carefully inspects it to ascertain whether it has been cut with a saw, or corroded by any strong acid. This dismal music lasts an hour. The whole expense of the prison to government does not exceed 16s. per day, and the few officers and guards, when Mr. Young was there, manage upwards of four hundred prisoners. He was confined from June 16, to September 7, and his account of the myriads of bugs, rats, mice, and other vermin is truly disgusting. The reader will however readily credit this report when he has been told of the revolting state of the city itself. Mrs. Baillie, in her recent Letters on Lisbon, says, "for three miles round Lisbon in every direction, you cannot for a moment get clear of the disgusting effluvia that issue from every house." Doctor Southey says "every kind of vermin that exists to punish the nastiness and indolence of man, multiplies in the heat and dirt of Lisbon. In addition to mosquitoes, the scolopendra is not uncommonly found here, and snakes sometimes intrude into the bedchamber. A small species of red ant likewise swarms over every thing sweet, and the Portuguese remedy is to send for the priest to exorcise them." The city is still subject to shocks of earthquake; the state of the police is horrible; street-robbery is common, and every thief is an assassin. The pocket-knife, which the French troops are said to have dreaded more than all the bayonets of either the Spanish or the Portuguese, is here the ready weapon of the assassin; and the Tagus receives many a corpse on which no inquest ever sits. The morals, in fact, of all classes in Lisbon appear to be in a dreadful state.

THE CARD

A TALE OF TRUTH(For the Mirror.)Young Lady Giddygad, came downFrom spending half a year in town,With cranium full of balls and plays,Routs, fêtes, and fashionable ways,Caus'd in her country-town, so quiet,Unus'd to modish din and riot,No small confusion and amaze,"Quite a sensation," is the phrase,Like that, which puss, or pug, may feelWhen rous'd from slumber by your heel,Or drowsy ass, at rider's knock,Or–should you term him block;Quoi qu'il en soit, first, gossips gape,Then envy, scandalize, and ape!Quoth Mrs. Thrifty: "Nancy, dear,My Lady sends out cards I hear,With, I suppose, 'tis now polite,Merely 'At Home,' on such a night,Now child, altho' I dare not sayWe can afford to be so gay,We're as well born as Lady G–And may be, as well bred as she!That is, quite in a sober waySo as we've nothing more to pay:For instance, when folks choose to come,And I don't choose to be 'At Home,'I'll have a notice stuck, you know,On the hall door, to tell them so:'Twill save our Rachel's legs you see,And soon the top will copy me!But, Nancy, d'ye hear, now writeThat I'm 'At Home' on Thursday night;'Tis a good fashion, for 'tis whatMost fashions in this age are notA saving one: ah, prithee think,How it saves time, and quills, and ink!"So, duteous Nancy seiz'd a pen,To ladies, and to gentlemenSent quickly out the cards; as quickCame one again: "Poh! fiddlestickAn answer, yes?—come, let me see,My spectacles!" cried Mistress T–"Hum—Mrs. Thrifty,—Thursday night—'AtHome'—oh malice! fiendish spite,"(Quoth the good dame in furious ire,Whilst the card, fed the greedy fire)"No, never, never, will I striveTo be genteel, as I'm alive,Beneath my own 'At Home' was cramm'd,There stay, good madam, and be d—d!"2M.L.B.MAHOMET THE GREAT AND HIS MISTRESS

An Anecdote(For the Mirror.)After the taking of Constantinople by the Turks, in the year 1453, several captives, distinguished either for their rank or their beauty, were presented to the victorious Mahomet the Great. Irene, a most beautiful Greek lady, was one of those unfortunate captives. The emperor was so delighted with her person, that he dedicated himself wholly to her embraces, spending day and night in her company, and neglected his most pressing affairs. His officers, especially the Janissaries, were extremely exasperated at his conduct; and loudly exclaimed against their degenerate and effeminate prince, as they were then pleased to call him. Mustapha Bassa, who had been brought up with the emperor from a child, presuming upon his great interest, took an opportunity to lay before his sovereign the bad consequences which would inevitably ensue should he longer persevere in that unmanly and base course of life. Mahomet, provoked at the Bassa's insolence, told him that he deserved to die; but that he would pardon him in consideration of former services. He then commanded him to assemble all the principal officers and captains in the great hall of his palace the next day, to attend his royal pleasure. Mustapha did as he was directed; and the next day the sultan understanding that the Bassas and other officers awaited him, entered the hall, with the charming Greek, who was delicately dressed and adorned. Looking sternly around him, the Sultan demanded, which of them, possessing so fair an object, could be contented to relinquish it? Being dazzled with the Christian's beauty, they unanimously answered, that they highly commended his happy choice, and censured themselves for having found fault with so much worth. The emperor replied, that he would presently show them how much they had been deceived in him, for that no earthly pleasure should so far bereave him of his senses, or blind his understanding, as to make him forget his duty in the high calling wherein he was placed. So saying, he caught Irene by the hair of her head, which he instantly severed from her body with his scimitar.

G.W.N.Select Biography

JUVENILE POETESS

MEMOIR OF LUCRETIA DAVIDSON,Who died at Plattsburgh, N.Y., August 27, 1825, aged sixteen years and eleven months[We hardly know how to give our readers an idea of the intense interest which this biographical sketch has excited in our mind; but we are persuaded they will thank us for adopting it in our columns. The details are somewhat abridged from No. LXXXII. of the Quarterly Review, (just published), where they appear in the first article, headed "Amir Khan, and other Poems: the remains of Lucretia Maria Davidson," &c., published at New York, in the present year. Prefixed to these "remains" is a biographical sketch, which forms the basis of the present memoir, and from the Poems are selected the few specimens with which it is illustrated.—ED.]

Lucretia Maria Davidson was born September 27, 1808, at Plattsburgh, on Lake Champlain. She was the second daughter of Dr. Oliver Davidson, and Magaret his wife. Her parents were in straitened circumstances, and it was necessary, from an early age, that much of her time should be devoted to domestic employments: for these she had no inclination, but she performed them with that alacrity which always accompanies good will; and, when her work was done, retired to enjoy those intellectual and imaginative, pursuits in which her whole heart was engaged. This predilection for studious retirement she is said to have manifested at the early age of four years. Reports, and even recollections of this kind, are to be received, the one with some distrust, the other with some allowance; but when that allowance is made, the genius of this child still appears to have been as precocious as it was extraordinary. Instead of playing with her schoolmates, she generally got to some secluded place, with her little books, and with pen, ink, and paper; and the consumption which she made of paper was such as to excite the curiosity of her parents, from whom she kept secret the use to which she applied it. If any one came upon her retirement, she would conceal or hastily destroy what she was employed upon; and, instead of satisfying the inquiries of her father and mother, replied to them only by tears. The mother, at length, when searching for something in a dark and unfrequented closet, found a considerable number of little books, made of this writing-paper, and filled with rude drawings, and with strange and apparently illegible characters, which, however, were at once seen to be the child's work. Upon closer inspection, the characters were found to consist of the printed alphabet; some of the letters being formed backwards, some sideways, and there being no spaces between the words. These writings were deciphered, not without much difficulty; and it then appeared that they consisted of regular verses, generally in explanation of a rude drawing, sketched on the opposite page. When she found that her treasures had been discovered, she was greatly distressed, and could not be pacified till they were restored; and as soon as they were in her possession, she took the first opportunity of secretly burning them.

These books having thus been destroyed, the earliest remaining specimen of her verse is an epitaph, composed in her ninth year, upon an unfledged robin, killed in the attempt at rearing it. When she was eleven years of age, her father took her to see the decorations of a room in which Washington's birthday was to be celebrated. Neither the novelty nor the gaiety of what she saw attracted her attention; she thought of Washington alone, whose life she had read, and for whom she entertained the proper feelings of an American; and as soon as she returned home, she took paper, sketched a funeral urn, and wrote under it a few stanzas, which were shown to her friends. Common as the talent of versifying is, any early manifestation of it will always be regarded as extraordinary by those who possess it not themselves; and these verses, though no otherwise remarkable, were deemed so surprising for a child of her age, that an aunt of hers could not believe they were original, and hinted that they might have been copied. The child wept at this suspicion, as if her heart would break; but as soon as she recovered from that fit of indignant grief, she indited a remonstrance to her aunt, in verse, which put an end to such incredulity.

We are told that, before she was twelve years of age, she had read most of the standard English poets—a vague term, excluding, no doubt, much that is of real worth, and including more that is worth little or nothing, and yet implying a wholesome course of reading for such a mind. Much history she had also read, both sacred and profane; "the whole of Shakspeare's, Kotzebue's, and Goldsmith's dramatic works;" (oddly consorted names!) "and many of the popular novels and romances of the day:" of the latter, she threw aside at once those which at first sight appeared worthless. This girl is said to have observed every thing: "frequently she has been known to watch the storm, and the retiring clouds, and the rainbow, and the setting sun, for hours."

An English reader is not prepared to hear of distress arising from straitened circumstances in America—the land of promise, where there is room enough for all, and employment for every body. Yet even in that new country, man, it appears, is born not only to those ills which flesh is heir to, but to those which are entailed upon him by the institutions of society. Lucretia's mother was confined by illness to her room and bed for many months; and this child, then about twelve years old, instead of profiting under her mother's care, had in a certain degree to supply her place in the business of the family, and to attend, which she did dutifully and devotedly, to her sick bed. At this time, a gentleman who had heard much of her verses, and expressed a wish to see some of them, was so much gratified on perusing them, that he sent her a complimentary note, enclosing a bank-bill for twenty dollars. The girl's first joyful thought was that she had now the means, which she had so often longed for, of increasing her little stock of books; but, looking towards the sick bed, tears came in her eyes, and she instantly put the bill into her father's hands, saying, "Take it, father; it will buy many comforts for mother; I can do without the books."

There were friends, as they are called, who remonstrated with her parents on the course they were pursuing in her education, and advised that she should be deprived of books, pen, ink, and paper, and rigorously confined to domestic concerns. Her parents loved her both too wisely and too well to be guided by such counsellors, and they anxiously kept the advice secret from Lucretia, lest it should wound her feelings—perhaps, also, lest it should give her, as it properly might, a rooted dislike to these misjudging and unfeeling persons. But she discovered it by accident, and without declaring any such intention, she gave up her pen and her books, and applied herself exclusively to household business, for several months, till her body as well as her spirits failed. She became emaciated, her countenance bore marks of deep dejection, and often, while actively employed in domestic duties, she could neither restrain nor conceal her tears. The mother seems to have been slower in perceiving this than she would have been had it not been for her own state of confinement; she noticed it at length, and said, "Lucretia, it is a long time since you have written any thing." The girl then burst into tears, and replied, "O mother, I have given that up long ago." "But why?" said her mother. After much emotion, she answered, "I am convinced from what my friends have said, and from what I see, that I have done wrong in pursuing the course I have. I well know the circumstances of the family are such, that it requires the united efforts of every member to sustain it; and since my eldest sister is now gone, it becomes my duty to do every thing in my power to lighten the cares of my parents." On this occasion, Mrs. Davidson acted with equal discretion and tenderness; she advised her to take a middle course, neither to forsake her favourite pursuits, nor devote herself to them, but use them in that wholesome alternation with the every day business of the world, which is alike salutary for the body and the mind. She therefore occasionally resumed her pen, and seemed comparatively happy.

How the encouragement which she received operated may be seen in some lines, not otherwise worthy of preservation than for the purpose of showing how the promises of reward affect a mind like hers. They were written in her thirteenth year.

Whene'er the muse pleases to grace my dull page,At the sight of reward, she flies off in a rage;Prayers, threats, and intreaties I frequently try,But she leaves me to scribble, to fret, and to sighShe torments me each moment, and bids me go write,And when I obey her she laughs at the sight;The rhyme will not jingle, the verse has no sense,And against all her insults I have no defence.I advise all my friends who wish me to write,To keep their rewards and their gifts from my sight,So that jealous Miss Muse won't be wounded in pride,Nor Pegasus rear till I've taken my ride.Let not the hasty reader conclude from these rhymes that Lucretia was only what any child of early cleverness might be made by forcing and injudicious admiration. In our own language, except in the cases of Chatterton and Kirke White, we can call to mind no instance of so early, so ardent, and so fatal a pursuit of intellectual advancement.

"She composed with great rapidity; as fast as most persons usually copy. There are several instances of four or five pieces on different subjects, and containing three or four stanzas each, written on the same day. Her thoughts flowed so rapidly, that she often expressed the wish that she had two pair of hands, that she might employ them to transcribe. When 'in the vein,' she would write standing, and be wholly abstracted from the company present and their conversation. But if composing a piece of some length, she wished to be entirely alone; she shut herself into her room, darkened the windows, and in summer placed her Aeolian harp in the window:" (thus by artificial excitement, feeding the fire that consumed her.) "In those pieces on which she bestowed more than ordinary pains, she was very secret; and if they were, by any accident, discovered in their unfinished state, she seldom completed them, and often destroyed them. She cared little for any of her works after they were completed: some, indeed, she preserved with care for future correction, but a great proportion she destroyed: very many that are preserved, were rescued from the flames by her mother. Of a complete poem, in five cantos, called 'Rodri,' and composed when she was thirteen years of age, a single canto, and part of another, are all that are saved from a destruction which she supposed had obliterated every vestige of it."

She was often in danger, when walking, from carriages, &c., in consequence of her absence of mind. When engaged in a poem of some length, she has often forgotten her meals. A single incident, illustrating this trait in her character, is worth relating:—She went out early one morning to visit a neighbour, promising to be at home to dinner. The neighbour being absent, she requested to be shown into the library. There she became so absorbed in her book, standing, with her bonnet unremoved, that the darkness of the coming night first reminded her she had forgotten her meals, and expended the entire day in reading.