Полная версия

Полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 14, No. 397, November 7, 1829

AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF A LANDAULET!

I dined one day at a bachelor's dinner in Lincoln's Inn-fields, and my wife having no engagement that evening, I gave my coachman a half holiday, and when he had set me down, desired him to put up his horses, as I should return home in a jarvey. At eleven, my conveyance arrived; the steps were let down, and, when down, they slanted under the body of the carriage; my foot slipped from the lowest step, and I grazed my shin against the second; but at last I surmounted the difficulty, and seating myself, sank back upon the musty, fusty, ill-savoured squabs of the jarvey.

I was about to undertake a very formidable journey; I lived in the Regent's Park; and as the horses that now drew me had been worked hard during the day, it seemed probable that some hours would elapse before I could reach my own door. Off they went, however; the coachman urged them on with whip and tongue: the body of the jarvey swung to and fro; the glasses shook and clattered; the straw on the floor felt damp, and rain water oozed through the roof, (for it was a landaulet). I felt chilled, and drew up the front window, at least I drew up the frame; but as it contained no glass, I was not the warmer for my pains; so I wrapped my cloak around me, and rather sulkily sank into a reverie. The vehicle still continued to rumble, and rattle, and shake, and squeak; I fell into a doze, caused by some fatigue and much claret, and gradually these sounds seemed to soften into a voice! I distinguished intelligible accents! I listened attentively to the low murmurs, and distinctly I heard, and treasured in my memory, what appeared to me to be the "Lament of the Landaulet!"

The poor body seemed to sigh, and the wheels became spokesmen!

"I am about fifteen years of age," (thus squeaked my equipage); "I was born in Long Acre, the birthplace of the aristocracy of my race, and Messrs. Houlditch were my parents.

"No four-wheeled carriage could possibly have entered upon life with brighter prospects; it is, alas! my hard lot to detail the vicissitudes that rendered me what I am.

"I was ordered by an earl, who was on the point of marriage with an heiress, and I was fitted up in the most expensive style. My complexion was pale yellow; on my sides I had coronets and supporters; my inside was soft and comfortable; my rumble behind was satisfactory; and my dicky was perfection, and provided with a hammercloth. My boots were capacious, my pockets were ample, and my leathers in good condition.

"When I stood at the earl's door on the morning of his marriage, it was admitted by all who beheld me, that a neater turn-out had never left Long Acre. Lightly did my noble possessor press my cushions, as I wafted him to St. George's Church, Hanover Square; and when the ceremony was over, and the happy pair sat side by side within me, the earl kissed the lips of his countess, and I felt proud, not of the rank and wealth of my contents, but because they were contented and happy.

"Oh, how merrily my wheels whirled in those days! I bore my possessors to their country-seat; I flew about the county returning wedding visits; I went to races, with sandwiches and champagne in my pockets; and I spent many a long night in the inn-yard, while my lord and lady were presiding at county assemblies.

"Mine was a life of sunshine and smiles. But ladies are capricious: the countess suddenly discovered that I was heavy. Now, if she wished me to be light-headed, why did she order a landaulet? She declared, too, that I was unfit for town service; gave new orders to Houlditch; took possession of a chariot fashioned eight months later than myself; sent me to Long Acre to be disposed of, and I became a secondhand article!

"My humiliation happened at an unlucky moment, for continual racketing in the country had quite unhinged me; I required bracing, and had quite lost my colour. My paternal relation, however, (Houlditch), undertook my repair, and I was very soon exhibited painted green, and ticketed, 'For sale secondhand.'

"It was now the month of May, when all persons of the smallest fashionable pretensions shun their country abodes and come to London, that they may escape the first fragrance of the flowers, the first song of the birds, the budding beauty of the forests and the fresh verdure of the fields. I therefore felt (as young unmarried ladies feel at the commencement of the season) that there was every chance of my finding a lord and master, and becoming a prominent ornament of his establishment.

"After standing for a month at Houlditch's, (who, by the by, was not over-civil to his own child, but made a great favour of giving me house-room), I one day found myself scrutinized by a gentleman of very fashionable appearance. He was in immediate want of a carriage; I was, fortunately, exactly the sort of carriage he required, and in a quarter of an hour the transfer was arranged.

"The gentleman was on the point of running away with a young lady; he was attached to her, four horses were attached to me, and I was in waiting at the corner of Grosvenor Street at midnight. I thought myself a fortunate vehicle; I anticipated another marriage, another matrimonial trip, another honeymoon. Alas! my present trip was not calculated to add to my respectability. My owner, who was a military man, was at his post at the appointed time: he seemed hurried and agitated; frequently looked at his watch; paced rapidly before one of the houses, and continually looked towards the drawing-room windows. At length a light appeared, the window was opened, and a female, muffled in a cloak and veil, stood on the balcony; she leaned anxiously forward; he spoke, and without replying she re-entered the room. The street-door opened, and a brisk little waiting-maid came out with some bundles, which she deposited in the carriage: the captain (for such was his rank) had entered the hall, and he now returned, bearing in his arms a fainting, weeping woman; he placed her by his side in the carriage: my rumble was instantly occupied by the waiting-maid and my master's man, and we drove off rapidly towards Brighton.

"The captain was a man of fashion; handsome, insinuating, profligate, and unfeeling. The lady—it is painful to speak of her: what she had been, she could never more be; and what she then was, she herself had yet to learn. She had been the darling pet daughter of a rich old man; and a dissipated nobleman had married her for her money when she was only sixteen. She had been accustomed to have every wish gratified by her doting parent; she now found herself neglected and insulted by her husband. Her father could not bear to see his darling's once-smiling face grow pale and sad, and he died two years after her marriage. She plunged into the whirlpool of dissipation, and tasted the rank poisons which are so often sought as the remedies for a sad heart. From folly she ran to imprudence; from imprudence to guilt;—and was the runaway wife happier than she who once suffered unmerited ill-usage at home? Time will show.

"At Brighton, my wheels rattled along the cliffs as briskly and as loudly as the noblest equipage there; but no female turned a glance of recognition towards my windows, and the eyes of former friends were studiously averted. I bore my lady through the streets, and I waited for her now and then at the door of the theatre; but at gates of respectability, at balls, and at assemblies, I, alas! was never 'called,' and never 'stopped the way.' Like a disabled soldier, I ceased to bear arms, and I was crest-fallen!

"This could not last: my mistress could little brook contempt, especially when she felt it to be deserved; her cheek lost its bloom, her eye its lustre; and when her beauty became less brilliant, she no longer possessed the only attraction which had made the captain her lover. He grew weary of her, soon took occasion to quarrel with her, and she was left without friends, without income, and without character. I was at length torn from her: it nearly broke my springs to part with her; but I was despatched to the bazaar in London, and saw no more of my lady.

(To be continued.)

FASHIONABLE NOVELS

It is well that hard words break no bones, else two or three gentlemen of literary notoriety would be in a sorry plight after reading the following passage in a recent Magazine. We stand by, and like the fellow in the play, bite our thumb:—

"Surely, surely, all men, women, and children, not cursed with the fatuity that would become a vice-president of the Phrenological Society, must by this time be about heartsick of what are called Novels of Fashionable Life. Only two men of any pretensions to superiority of talent have had part in the uproarious manufacture of this ware, that has been dinned in our ears by trumpet after trumpet, during the last six or seven years. Mr. Theodore Hook began the business—a man of such strong native sense and thorough knowledge of the world as it is, that we cannot doubt the coxcombry which has drawn so much derision on his sayings and doings was all, to use a phrase which he himself has brought into fashion, humbug. He could not cast his keen eyes over any considerable circle of society in this country, without perceiving the melancholy fact, that the British nation labours under a universal mania for gentility—all the world hurrying and bustling in the same idle chase—good honest squires and baronets, with pedigrees of a thousand years, and estates of ten thousand acres—ay, and even noble lords—yea, the noblest of the noble themselves (or at least their ladies), rendered fidgety and uncomfortable by the circumstance of their not somehow or other belonging to one particular little circle in London. Comely round-paunched parsons and squireens, again, all over the land, eating the bread of bitterness, and drinking the waters of sorrow, because they are, or think they are, tipt the cold shoulder by these same honest squires and baronets, &c. &c. &c. who, excluded from Almack's, in their own fair turn and rural sphere enact nevertheless, with much success, the part of exclusives—and so downwards—down to the very verge of dirty linen. The obvious facility of practising lucratively on this prevailing folly—of raising 700l., 1000l., or 1500l. per series, merely by cramming the mouths of the asinine with mock-majestic details of fine life—this found favour with an indolent no less than sagacious humorist; and the fatal example was set. Hence the vile and most vulgar pawings of such miserables as Messrs. Vivian Grey and "The Roué"—creatures who betray in every page, which they stuff full of Marquess and My Lady, that their own manners are as gross as they make it their boast to show their morals. Hence, some two or three pegs higher, and not more, are such very very fine scoundrels as the Pelhams, &c.; shallow, watery-brained, ill-taught, effeminate dandies—animals destitute apparently of one touch of real manhood, or of real passion—cold, systematic, deliberate debauchees, withal—seducers, God wot! and duellists, and, above all, philosophers! How could any human being be gulled by such flimsy devices as these?

"These gentry form a sort of cross between the Theodorian breed of novel and the Wardish—the extravagantly overrated—the heavy, imbecile, pointless, but still well-written, sensible, and, we may even add, not disagreeable, Tremaine and De Vere. The second of these books was a mere rifacimento of the first; and, fortunately for what remained of his reputation, Mr. Robert Ward has made no third attempt. He has much to answer for; e.g. if we were called upon to point out the most disgusting abomination to be found in the whole range of contemporary literature, we have no hesitation in saying we should feel it our duty to lay our finger on the Bolingbroke-Balaam of that last and worst of an insufferable charlatan's productions—Devereux.

BRUSSELS IN 1829

For the education of youth of both sexes, Brussels is one of the best stations on the continent, and is a good temporary residence for Englishmen whose means are limited. The country is plentiful, and consequently every article of living moderate. It is near England, the government is mild, and there is no restraint in importing English books, though their own press is any thing but free.

The population of Brussels is rated at nearly 100,000, of which above 20,000 are paupers, supported by the government and voluntary contributions. The population is rapidly increasing. The number of foreigners in the winter of 1828 was between seven and eight thousand, of which half the number were English. Many families settle for a season, and take their flight south, or return home in June; but the greatest number are stationary for the education of their children. An English clergyman, formerly a teacher at Harrow, has an establishment for boys, well conducted, and the expense does not exceed fifty guineas a year. There are several seminaries for girls, also superintended by Englishwomen, with French teachers. Masters in every department are excellent, so that few places afford better schools for education.

The air in the upper part of the city is salubrious, and the climate, perhaps, better on the whole than England; but the winters are sharper, and the summers hotter; fogs are less frequent, and the spring generally sets in a fortnight earlier than in any part of Great Britain.

Our countrymen will be disappointed who settle in Brussels as a place of amusement, for no capital can be more dull; and the natives are not ready of access, which is probably as much the fault of their visitors as themselves. As a station for economy, it can be highly recommended, provided no trust is put in servants, and every thing is paid for with ready money. The writer of this article resided in Brussels for a dozen years, and he knows this from experience. If an establishment, large or small, is well regulated, a saving of fifty per cent, may be made, certainly, in housekeeping, compared with London. House-rent is dearer in proportion with other articles of living, and the taxes are daily augmenting. The horse-tax is more than double that of England; and the king of the Netherlands can boast that he is the only sovereign in Europe who has a tax on female labour. William Pitt attempted a similar measure, but was mobbed by the housemaids, and abandoned it.—New Monthly Magazine.

The Gatherer

A snapper up of unconsidered trifles.SHAKSPEARE.CURIOUS DISCOVERY OF A ROBBERY

Lysons in his "Environs of London," says, "In a room adjoining to the south-side of the saloon, in the manor-house, at Charlton, in Kent, is a chimney-piece, with a slab of black marble so finely polished, that Lord Downe is said to have seen in it a robbery committed on Blackheath; the tradition adds, that he sent out his servants, who apprehended the thieves." Dr. Plot makes the story more marvellous, by laying the scene of the robbery at Shooter's Hill; he also says, "Thus in a chimney-piece at Beauvoir Castle, might be seen the city and cathedral of Lincoln, and in another at Wilton, the city and cathedral of Sarum."

P.T.W."VERY BAD."

A tyro interrogating a classical wag on the labours and sufferings of Homer, was shown the Iliad, and told that it was composed under great deprivation. Pointing to the edition, he inquired, if that was all the Iliad; to which he received as answer, that that was not all the ill he had, as Homer was obliged to sing it, to procure a little bread.

EPIGRAM

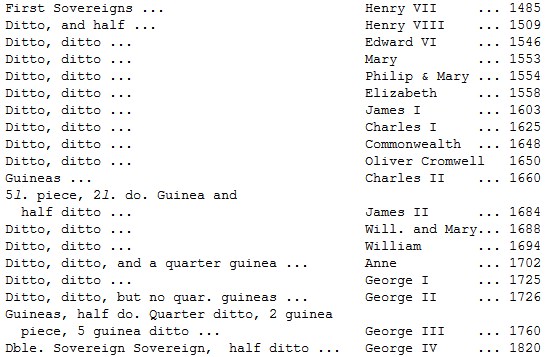

Young Sloeleaves vaunting he could traceHis line to Julius Caesar,Was gall'd to hear a wag exclaim,"The Celtae, if you please, Sir!"Q IN THE CORNER.Inscription over the Hive public-house, in Snargate Street, DovorWithin this HiveWe're all alive,Good liquors make us funny,If you are dry,Step in and tryThe flavour of our honey.SOVEREIGNS AND GUINEAS,

And the reigns in which they have been coined

EPIGRAMS ON THE FEES DEMANDED FOR SEEING WESTMINSTER ABBEY

Dame Godly desired the Abbey to view,Admittance, one sixpence, demanded the clerk,Which modest request in astonishment wrapt her,How long will you such imposition pursue?Faith ma'am, as to that we are left in the dark,But I think, for my part, to the end of the Chapter.6Down with your cash, the Verger cries,How mean'st thou this? John Bull replies,What law protects th' extortion?Stop, gentle friend—what's law to us?The law's your own—so make no fuss,The profits are our portion.Poets and prophets 'mongst the ancient RomansWere deemed the same, and this our pockets rue,For on this creed is built our sacred showman's,Who has his poets and his profits too.EPITAPH IN BRENTWOOD CHURCHYARD, ESSEX

Here lyes Isaac Greentree.A wag passing through the churchyard, wrote as follows:—

There is a time when these green trees shall fall,And Isaac Greentree rise above them all.GALLOWAYS—WHY PARTICULAR HORSES SO CALLED

Galloway is a county in Scotland that lies the most to the south and the nearest to Ireland. This county gives name to a particular breed of horses of a middling size, which are strong, active, hardy, and serviceable.

Tradition reports that this kind of horse sprung from some Spanish stallions, who swam on shore from some of the ships of the famous Spanish Armada wrecked on the coast.

C.K.W.WARNING TO YOUNG LADIES

Intended as an "accompaniment" to a celebrated piece of Music, by CravenOh! ladies fair, tho' smooth the air,I send you now, I pray take care—Lest "THE LIGHT BARK" be, after all,Foredoom'd to perish in a squall!PRINTER'S DEVIL.ANNUALS FOR 1830

With the next number of "THE MIRROR," will be published the first SUPPLEMENTARY SHEET of the

SPIRIT OF THE ANNUALS FOR 1830,With a fine Engraving from one of the most splendid embellishments of these popular works. The SUPPLEMENT will contain "the Amulet"—"Friendship's Offering," and Notices of as many more volumes as can consistently be brought within the compass of one sheet.

LIMBIRD'S EDITION OF THE

Following Novels is already Published:

1

Dr. Donne resided in a house of Sir R. Drury. Vide Life by honest Izaak Walton.

2

He married a daughter of one of the Fine Barber-women of Drury Lane.

3

A few weeks since we gave a copy of Robinson Crusoe to a young man, "whose education had been neglected," and who had never read this delightful book: the account of his delight from its perusal has more than recompensed us tenfold.

4

We should like to see a volume of poems written by Wordsworth, and illustrated by Gainsborough. How delightfully too would a few of the poet's lines glib off in a Juvenile Annual.

5

He was sent at the age of ten years to a school at Wexin, the master of which was so severe as entirely to destroy his spirits, and repress the early indications of his extraordinary talents.

6

The Dean and Chapter of Westminster are supposed to receive the money paid for seeing the Abbey.