Полная версия

Полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 14, No. 397, November 7, 1829

An extract then follows from an account of payments to "Blew Gownis," by Sir Robert Melvill, of Murdocarney, treasurer-depute of King James VI., furnished to the author of "Waverley," by an officer of the Register House; after which Sir Walter proceeds as follows:—

"I have only to add, that although the institution of King's Bedesmen still subsists, they are now seldom to be seen in the streets of Edinburgh, of which their peculiar dress made them rather a characteristic feature.

"Having thus given an account of the genus and species to which Edie Ochiltree appertains, the author may add, that the individual he had in his eye was Andrew Gemmells, an old mendicant of the character described, who was many years since well known, and must still be remembered, in the vales of Gala, Tweed, Ettrick, Yarrow, and the adjoining country.

"The author has in his youth repeatedly seen and conversed with Andrew, but cannot recollect whether he held the rank of Blue Gown. He was a remarkably fine old figure, very tall, and maintaining a soldier-like, or military manner and address. His features were intelligent, with a powerful expression of sarcasm. His motions were always so graceful, that he might almost have been suspected of having studied them; for he might, on any occasion, have served as a model for an artist, so remarkably striking were his ordinary attitudes. Andrew Gemmells had little of the cant of his calling; his wants were food and shelter, or a trifle of money, which he always claimed, and seemed to receive, as his due. He sang a good song, told a good story, and could crack a severe jest with all the acumen of Shakspeare's jesters, though without using, like them, the cloak of insanity. It was some fear of Andrew's satire, as much as a feeling of kindness or charity, which secured him the general good reception which he enjoyed every where. In fact, a jest of Andrew Gemmells, especially at the expense of a person of consequence, flew round the circle which he frequented, as surely as the bon-mot of a man of established character for wit glides through the fashionable world. Many of his good things are held in remembrance, but are generally too local and personal to be introduced here.

"Andrew had a character peculiar to himself among his tribe, for aught I ever heard. He was ready and willing to play at cards or dice with any one who desired such amusement. This was more in the character of the Irish itinerant gambler, called in that country a carrow, than of the Scottish beggar. But the late Reverend Doctor Robert Douglas, minister of Galashiels, assured the author, that the last time he saw Andrew Gemmells, he was engaged in a game at brag with a gentleman of fortune, distinction, and birth. To preserve the due gradations of rank, the party was made at an open window of the château, the laird sitting on his chair in the inside, the beggar on a stool in the yard; and they played on the window-sill. The stake was a considerable parcel of silver. The author expressing some surprise, Dr. Douglas observed, that the laird was no doubt a humorist or original; but that many decent persons in those times would, like him, have thought there was nothing extraordinary in passing an hour, either in card-playing or conversation, with Andrew Gemmells.

"This singular mendicant had generally, or was supposed to have, as much money about his person, as would have been thought the value of his life among modern footpads. On one occasion, a country gentleman, generally esteemed a very narrow man, happening to meet Andrew, expressed great regret that he had no silver in his pocket, or he would have given him sixpence:—'I can give you change for a note laird,' replied Andrew.

"Like most who have arisen to the head of their profession, the modern degradation which mendicity has undergone was often the subject of Andrew's lamentations. As a trade, he said, it was forty pounds a year worse since he had first practised it. On another occasion he observed, begging was in modern times scarcely the profession of a gentleman, and that if he had twenty sons, he would not easily be induced to breed one of them up in his own line. When or where this laudator temporis acti closed his wanderings, the author never heard with certainty; but most probably, as Burns says—

"–he died a cadger-powny's deathAt some dike side.""The author may add another picture of the same kind as Edie Ochiltree and Andrew Gemmells; considering these illustrations as a sort of gallery, open to the reception of any thing which may elucidate former manners, or amuse the reader.

"The author's contemporaries at the university of Edinburgh will probably remember the thin wasted form of a venerable old Bedesman, who stood by the Potter-row Port, now demolished; and, without speaking a syllable, gently inclined his head, and offered his hat, but with the least possible Degree of urgency, towards each individual who passed. This man gained, by silence and the extenuated and wasted appearance of a palmer from a remote country, the same tribute which was yielded to Andrew Gemmells's sarcastic humour and stately deportment. He was understood to be able to maintain a son a student in the theological classics of the University, at the gate of which the father was a mendicant. The young man was modest and inclined to learning, so that a student of the same age, and whose parents were rather of the lower order, moved by seeing him excluded from the society of other scholars when the secret of his birth was suspected, endeavoured to console him by offering him some occasional civilities. The old mendicant was grateful for this attention to his son, and one day, as the friendly student passed, he stooped forward more than usual, as if to intercept his passage. The scholar drew out a halfpenny, which he concluded was the beggar's object, when he was surprised to receive his thanks for the kindness he had shown to Jemmie, and at the same time a cordial invitation to dine with them next Sunday, 'on a shoulder of mutton and potatoes,' adding, 'ye'll put on your clean sark, as I have company.' The student was strongly tempted to accept of this hospitable proposal, as many in his place would probably have done; but as the motive might have been capable of misrepresentation, he thought it most prudent, considering the character and circumstances of the old man, to decline the invitation.

"Such are a few traits of Scottish mendicity, designed to throw light on a novel in which a character of that description plays a prominent part. We conclude, that we have vindicated Edie Ochiltree's right to the importance assigned him; and have shown, that we have known one beggar take a hand at cards with a person of distinction, and another give dinner parties."

The curious reader who is anxious to pursue the character still further, will be gratified with "a few particulars with which his biographer appears to be unacquainted,"—by a Correspondent of the Literary Gazette, No. 664.

UNLUCKY TEXT

Poor Dr. Sheridan, in an unguarded moment, but in as guiltless a spirit as characterized the Vicar of Wakefield, chose for his text, upon the anniversary of the succession of the House of Hanover, "Sufficient for the day is the evil thereof." Although the sermon did not contain a single political allusion that could have caused uneasiness, or should have given offence, yet it was recorded in judgment against him, and obstructed his preferment ever after.—Southey's Colloquies.

The Naturalist

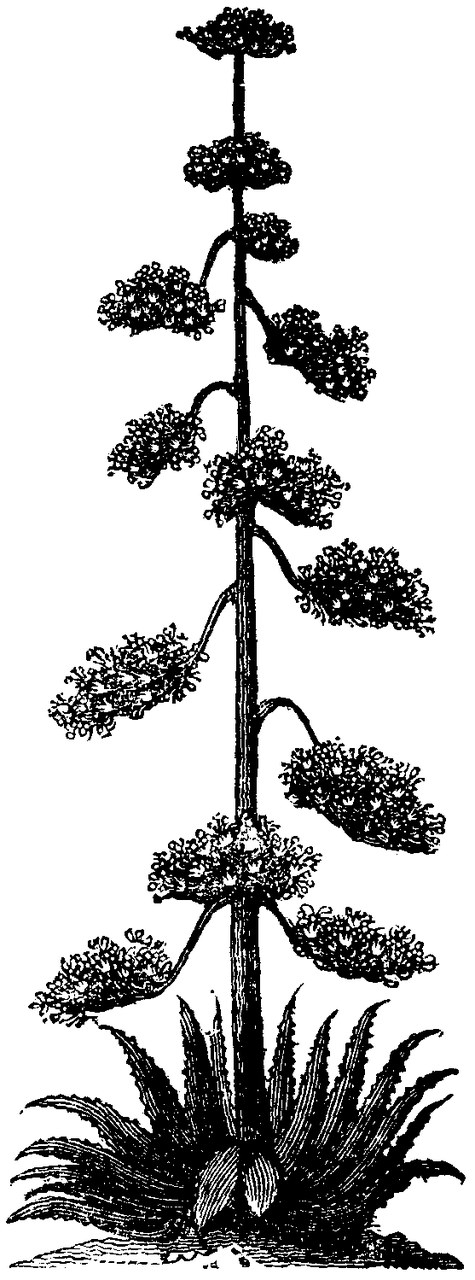

THE AMERICAN ALOE

An American Aloe (Agave Americana) is one of the most superb exhibitions in the whole vegetable kingdom. The plant, when vigorous, rises upwards of twenty feet high, and branches out on every side, forming a kind of pyramid, of greenish yellow flowers, in thick clusters at every joint. We often meet with the aloe in our conservatories, and it has been known to flourish in the open air. A Correspondent of the Gardener's Magazine, writing from Gwrich Castle, Abergelay, Denbighshire, tells us that "about eight years back he pulled down one of his hot-houses, in which stood a large American Aloe, known to be 68 years of age. It was in a box about two feet square, and the plant was so large that he determined not to put it in the new house then building; it was, in consequence, placed alongside the south wall in the corner (not expecting it to live,) where it has been ever since, never having been watered in summer, nor matted nor attended to in winter, and it is now as vigorous and as healthy (if not more so) than before. The box was not buried in the ground, and is now falling to pieces. The garden is about 100 yards from the sea."

It is no fable that the Aloe grows about a hundred years (a few more or less) before it blooms; and, after yielding its seed, the stem withers and dies. If we remember right, a beautiful specimen in full bloom, was exhibited three or four years since at the Argyll Rooms, in Regent Street.

It may be as well to mention that the sharp-pointed leaves have been known to inflict serious injury. In the Lancet, No. 313, vol. ii., a case is recorded of a young gardener, who whilst watering some plants in a gentleman's garden, at Camberwell, accidentally struck his hand against an aloe plant, one of the prickles of which passed into the last joint of his lefthand little finger; he regarded the circumstance at the time as but of trifling consequence, on account of its causing him but slight inconvenience; neither were the effects worth notice until two days after the accident, when the part put on a white appearance, and the finger became very stiff, swollen, and painful; these symptoms increased, and by the following morning the whole hand and arm, as far as the elbow, had attained an exceedingly large size. After suffering about two months, the poor fellow was removed into St. Thomas's Hospital, where the diseased arm was amputated by Mr. Travers, and the patient soon recovered his accustomed good health.

MOLES

In those districts where moles abound, it may be remarked that some of the mole-hills are considerably larger than others. When a hill of enlarged dimensions is thus discovered, we may be almost certain of finding the nest, or den of the mole near it, by digging to a sufficient depth. The fur of the mole is admirably adapted from its softness and short close texture for defending the animal from subterraneous damp, which is always injurious, more or less to non-amphibious animals; and in this climate, no choice of situation could entirely guard against it. It is a singular fact that there are no moles in Ireland. May not the dampness of the climate account for their not thriving there?—Edinburgh Lit. Gaz.

CHANGES IN ANIMALS

All domestic mammiferous animals introduced into America have become more numerous than the indigenous animals. The hog multiplies very rapidly, and assumes much of the character of the wild boar. Cows did not at first thrive, but, in St. Domingo, only twenty-seven years after its first discovery, 4,000 in a herd was not uncommon, and some herds of 8,000 are mentioned. In 1587, this island exported 35,444 hides, and New Grenada 64,350. Cows never thrive nor multiply where salt is wanting either in the plants or in the water. They give less milk in America, and do not give milk at all if the calves be taken from them. Among horses the colts have all the amble, as those in Europe have the trot: this is probably a hereditary effect. Bright chestnut is the prevailing colour among the wild horses. The lambs which are not from merinos, but the tana basta and burda of the Spaniards, at first are covered with wool, and when this is timely shorn, it grows again; if the proper time is allowed to elapse, the wool falls off, and is succeeded by short, shining, close hair, like that of the goat in the same climate. Every animal, it would appear, like man, requires time to accustom itself to climate.

THE GREAT AMERICAN BITTERN

A most interesting and remarkable circumstance we learn from the Magazine of Natural History, attends the great American Bittern; it is that it has the power of emitting a light from its breast equal to the light of a common torch, which illuminates the water so as to enable it to discover its prey. As this circumstance is not mentioned by any naturalist, the correspondent of the journal in question, took every precaution to determine, as he has done, the truth of it.

Notes of a Reader

BRITISH SEA SONGS

One of our earliest naval ballads is derived from the Pepys Collection, and is supposed to have been written in the reign of Queen Elizabeth. It records the events of a sea-fight in the reign of Henry the Eighth, between Lord Howard and Sir Andrew Barton, a Scotch pirate; and it is rendered curious by the picture it presents of naval engagements in those days, and by a singular fact which transpires in the course of the details; namely, that the then maritime force of England consisted of only two ships of war. In Percy's "Reliques of Ancient Poetry," there is another old marine ballad, called the "Winning of Cales," a name which our sailors had given to Cadiz. This affair took place in June, 1596; but the description of it in the old song presents nothing peculiar, or worthy of attention as regards naval manners. From this period, I cannot at present call to mind any sea song of importance till Gay's "Black-eyed Susan," which, you know, has maintained its popularity to the present hour, and which deserves to have done so, no less on account of the beauty of the verses, than of the pathetic air in the minor to which they are set. This was, at no great length of time, succeeded by Stevens's "Storm," a song which, I believe you will all allow, stands deservedly at the head of the lyrics of the deep. The words are nautically correct, the music is of a manly and original character, and the subject-matter is one of the most interesting of the many striking incidents common to sea-life. These fine ballads, if I mistake not, were succeeded by one or two popular songs, with music by Dr. Arne; then came those of Dibdin, which were in their turn followed by a host of compositions, distinguished more by the strenuous, robust character of the music, than by poetical excellence, or professional accuracy in the words. The songs in which the words happened to be vigorous and true—(such, for example, as Cowper's noble ballad called the "Castaway," and the "Loss of the Royal George,") were not set to music; but the powers of Shield, Davy, and others, were wasted on verses unworthy of their compositions. Among these, the foremost in excellence is the "Arethusa," a composition on which the singing of Incledon, and the bold, reckless, original John-Bull-like character of the air by Shield, or ascribed to him, have fixed a high reputation. Davy's "Bay of Biscay," deserves its popularity; and the "Sailor Boy," "The Old Commodore," and one or two other melodies by Reeve, (who, though not much of a musician, was an admirable melodist,) abound also in the qualities which I have already alluded to, as peculiar to the national music adapted to sea songs.—Blackwood's Magazine.

MAKING A BOOK

Lady Morgan gives the following process by which her "Book of the Boudoir" was manufactured: "While the fourth volume of the O'Briens," says her ladyship, "was going through the press, Mr. Colburn was sufficiently pleased with the subscription (as it is called in the trade) to the first edition, to desire a new work from the author. I was just setting off for Ireland, the horses literally putting to, [how curious!] when Mr. Colburn arrived with his flattering proposition. [How apropos!] I could not enter into any future engagement; [how awkward!] and Mr. Colburn taking up a scrabby MS. volume which the servant was about to thrust into the pocket of the carriage, asked, 'What was that?' [How touchingly simple!] I said it was 'one of many volumes of odds and ends de omnibus rebus;' and I read him the last entry I had made the night before, on my return from the opera. [How very obliging, considering that the horses were literally put to!] 'This is the very thing!' said the 'European publisher;' [how charming! and yet how droll!] and if the public is of the same opinion, I shall have nothing to regret in thus coming, though somewhat in dishabillé, before its tribunal."

Blackwood's Magazine.APPARITIONS

Dr. Southey's opinion on apparitions deserves to be carried to the controversial account of this ever-interesting question:—"My serious belief amounts to this, that preternatural impressions are sometimes communicated to us for wise purposes; and that departed spirits are sometimes permitted to manifest themselves."—Colloquies.

THE FEUDAL SYSTEM

The system of servitude, which prevailed in the earlier periods of our history was not of that unmitigated character that may be supposed. "No man in those days could prey upon society, unless he were at war with it as an outlaw—a proclaimed and open enemy. Rude as the laws were, the purposes of law had not then been perverted;—it had not been made a craft;—it served to deter men from committing crimes, or to punish them for the commission;—never to shield notorious, acknowledged, impudent guilt, from condign punishment. And in the fabric of society, imperfect as it was, the outline and rudiments of what it ought to be were distinctly marked in some main parts, where they are now wellnigh utterly effaced. Every person had his place. There was a system of superintendence everywhere, civil as well us religious. They who were born in villainage, were born to an inheritance of labour, but not of inevitable depravity and wretchedness. If one class were regarded in some respects as cattle, they were at least taken care of; they were trained, fed, sheltered, and protected; and there was an eye upon them when they strayed. None were wild, unless they were wild wilfully, and in defiance of control. None were beneath the notice of the priest, nor placed out of the possible reach of his instruction and his care. But how large a part of your population are, like the dogs of Lisbon and Constantinople, unowned, unbroken to any useful purpose, subsisting by chance or by prey; living in filth, mischief, and wretchedness; a nuisance to the community while they live, and dying miserably at last!"—Ibid.

THE STEAM BOAT ILLUSTRATED

By one of "the Islington, Gray's Inn Lane, and New Road Grand Literary, Scientific, and Philosophical InstitutionHow wondrous is the science of mechanism! how variegated its progeny, how simple, yet how compound! I am propelled to the consideration of this subject by having optically perceived that ingenious nautical instrument, which has just now flown along like a mammoth, that monster of the deep! You ask me how are steam-boats propagated? in other words, how is such an infinite and immovable body inveigled along its course? I will explain it to you. It is by the power of friction; that is to say, the two wheels, or paddles turning diametrically, or at the same moment, on their axioms, and repressing by the rotundity of their motion the action of the menstruum in which the machine floats,—water being, in a philosophical sense, a powerful non-conductor,—it is clear, that in proportion as is the revulsion so is the progression; and as is the centrifugal force, so is the—."

"Pooh!" cried Uncle John, "let us have some music."

New Monthly Magazine.LAWS FOR THE POOR

Every civilized state in the world, except Ireland, has prevented the extortion of the landlords, by institutions, either springing from the nature of society, or established by positive legal enactments.

In Austria, great exertions are made for the poor.—Vide "Reisbeck's Travels through Germany," p. 79; and "Este's Journey," p. 337.

In Bavaria, there are laws obliging each community to maintain its own poor.—Vide "Count Rumford's Establishment of Poor in Bavaria," chap. 1.

In Protestant Germany they are even better provided for.—Vide "Henderson's Tour in Germany," p. 74.

In Russia, the aged and infirm are provided with food and raiment by law, at the expense of the owner of the estate.—"Clarke's Travels in Russia." For others who may want, there is a college of provision in each government.—"Took's Russian Empire," vol. ii. p. 181.

In Livonia and Poland, the lord is bound by law to provide for the serf.—Vide "Bavarian Transactions," vol. iii.

In Northern Italy and Sicily, the crop is equally divided between landlord and tenant.—Vide "Sismondi's Italy." And the revenues of the church support the poor.

In imperial France, though the land had been divided by an Agrarian law, and cultivated, yet the Octroi, with other revenues, were devoted to the poor.

In Hungary, though feudal slavery gives an interest to the lord of the soil in the life of his serf, yet the law insists upon the provision of food, raiment and shelter. In Switzerland, though the Agrarian law is in force, and the governments purchase corn to keep down the retail prices, yet there is a provision for the poor.—Vide "Sismondi's Switzerland," vol. 1. p. 452. In Norway there is a provision for the poor.—Clarke's "Scandinavia," p. 637.

In Sweden, the most moral country in the world, the poor are maintained in the same manner as in England; a portion of the parochial assessment is devoted by law to education.—James's "Tour through Sweden," p. 105.

In Flanders there are permanent funds, &c. for the sustentation of the poor. Vide Radcliff's "Report on the Agriculture of Flanders." And there are in the Netherlands seven great workhouses.

The Dutch poor laws do not differ much from our own.–Vide Macfarlan's "Inquiries concerning the Poor," p. 218.

Even in Iceland, there is a provision for the poor.—Vide Han's "Iceland." Also in Denmark.—Vide p. 292, Jacob's "Tracts on the Corn Laws." In America there are poor laws.—Vide Dr. Dwight's "Travels," vol. iv. p. 326. In Scotland the English system is rapidly extending; and where the poor laws are not introduced, there are a great many of the miseries which are found in Ireland.—Vide "Evidence of A. Nimmo, Esq. before the Lords' Committee on Ireland, 1824." This gentleman thinks, that if they had been earlier introduced, Scotland would be now a richer country. He also states, that the average expense of supporting idle mendicants in Ireland, exceeds one million and a half annually, by the contribution of more than a ton of potatoes from each farm house, to encourage a system of licentious idleness, profligacy, insolence, and plunder; and the grand jury presentments amount annually to a million.—Monthly Mag.

In Turkey, nailing by the ears is an operation performed on bakers, for selling light bread. There is a hole cut in the door for the back of the culprit's head; the ears are then nailed to the panel; he is left in this position till sunset, then released; and seldom sustains any permanent injury from the punishment, except in his reputation. Perjury is an offence which is so little thought of, that it is visited with the mildest of all their punishments. The offender is set upon an ass, with his face to the tail, and a label on his back, with the term scheat or perjurer. In this way he is led about to the great amusement of the multitude, and even of his associates.

SCHOOL DAYS

Linnaeus long retained an unpleasant recollection of his school days;5 it is common to call this period of human life, a happy one, but that existence must have been very wretched, of which, the time passed at school has been the happiest part; it is sufficiently apparent even to superficial observers that the mind cannot, in early life, be sufficiently matured for high enjoyment; the most exquisite of our pleasures, are intellectual, and cannot be relished until the mental faculties have been cultivated and expanded.—Clayton's Sketches in Biography.

SPIRIT OF THE PUBLIC JOURNALS