Полная версия

Полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 14, No. 397, November 7, 1829

Various

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction / Volume 14, No. 397, November 7, 1829

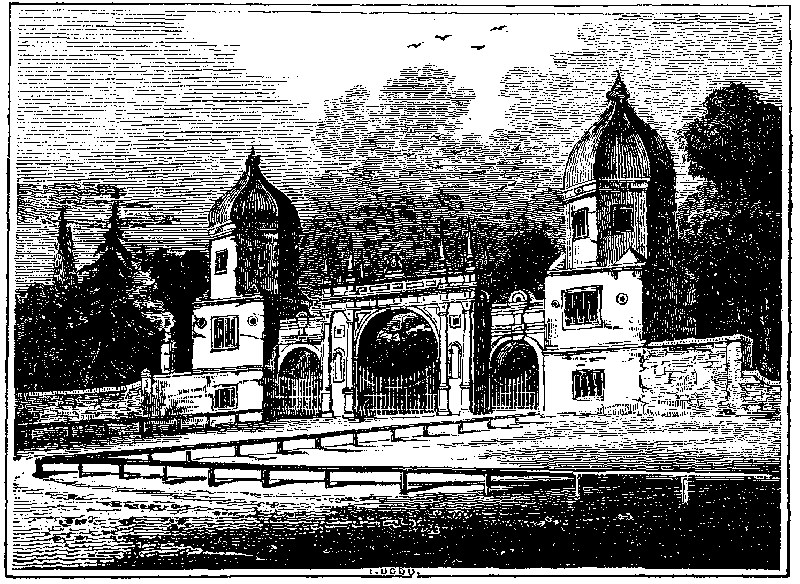

Burleigh, Northamptonshire

The above is a view of the grand screen and entrance lodges to Burleigh, or Burghley, the seat of the Cecil family, and now the property of the Marquess of Exeter. The house and principal part of the demesne, are within the parish of Stamford St. Martin, in the church of which are some costly monuments to several eminent persons of the Cecil family; and this estate gave title to William Cecil, Baron Burleigh, in 1570. The park was formed, and the mansion, which is one of the most splendid in the kingdom, was mostly built by the great Lord Treasurer, in the time of Queen Elizabeth, and the following inscription, over one of the entrances, within a central court, records the era of this work:—"W. DOM. DE BVRGHLEY, 1577." Beneath the turret is the date of 1585, when some grand additions were made to the mansion; and the above Grand Entrance, towards the north, appears to have been added in 1587. Since these dates, several material alterations and additions have been made by subsequent possessors; and the whole, as a building, with its vast and varied collection of works of art, is one of the most magnificent show-houses in England. The spacious and finely wooded park and large lake are also very fine. The house surrounds a square court, to the east of which is the great hall, kitchen, various domestic offices, with spacious stables, coach-houses, &c.—all indicative of the splendid hospitalities of the Elizabethean age and old English character. The south front commands a fine sloping lawn, with a broad sheet of water, formed by Brown, together with some interesting park-scenery; the western side has nearly the same views, with the advantage of distant objects in Rutlandshire, Lincolnshire, and the spires of Stamford. From the north front the ground gradually slopes to the river Welland. A complete list of the pictures and valuable curiosities of Burleigh will be found in a Guide published by the ingenious Mr. Drakard, bookseller, of Stamford, as well as in that gentleman's excellent History of Stamford.

About two miles west of Burleigh, are the ruins of Wothorp, or Worthorp House. According to Camden, a mansion of considerable size was erected here by Thomas Cecil, the first Earl of Burleigh, who jocularly said, "he built it only to retire to out of the dust, while his great house at Burleigh was sweeping." After the Restoration the Duke of Buckingham resided here for some years.

THE LION'S ROAR

(For the Mirror.)Sad is my grief, and violent my rage,Furious I knock my head against the rail,That damns me to this miserable cage;Fierce as a Jack Tar with his well chew'd tail,I dash my spittle on the ground, and roarLoud as the trump to bid us be no more.I am the doughty, the illustrious beast,Called Leo, father of the Panther young,Tho' last begotten, not belov'd the least,You all know I have a roast beef tongue:Then, hear my John Bull clamour, hear my shout!Why, why the d–, roust we all tarn out?Did I not keep a beef-eater belowTo show the ladies to my monarch cave?I kept a constant levee day of show,And seldom monarchs so polite behave!You paid far less for seeing me, I ken,Than porterage for seeing noble men.Did I not eat my supper in your presence.And gnaw the beef bone with a greedy tusk?Did you not shudder at the marrow's essence,Not quite so beautiful or sweet as musk?Did I not ope my lion fauces widerThan is the difference 'twixt Moore and Ryder?Then, why the d–?—I'm obliged to swear!Must we turn out, to grace the monarch's mews,From the thronged Strand which seemed our native air,And, where as thick as piety in pews,We growl'd within our dens, nor hop'd to change,Nor wish'd, Instead of Exeter, a change.Sweet lovely corner, neighb'ring the Lyceum,Lord of whose showy board I used to crow.Frighting my brethren when folks came to see 'em,Or cutlery of Mr. Clarke below;I mourn thee in the King's Mews, Mr. CrossGet Mr. Southey's muse to sing my loss.Yes, I am chang'd, like shillings from the MintSent forth to find another one's protection!Chang'd as palaver which the members printAnd do not follow after their election!Ah! Mr. Cross, your gratitude is low,You might have ask'd me where I wish'd to go.Since we have turn'd out, like a ministerWhose day of residence on loaves and fishes,Finding himself unable to defer,He offers up, as if 'twere to his wishes;Listen, tho' lately coming, to my moan,And then I'll tell you where we should have gone.The Monkeys should have dwelt in the Arcade,And join'd their fellows, and their brethren ApeSat in the shop where clothes are ready made,To show how elegant they fit the shape!The Bears gone westward also, ne'er to rangeThe city, lest they got upon the Change.The Tigers, with their talons might have gotA place as blood letters to Dr. Brooks!The Ounces found themselves a cosy spotIn a confectioner's or pastrycook's,And yet I question howsoe'er they bake,That sixteen ounces make not a pound-cake.And, O, you Elephant!—I beg your pardon!Dead Chunee! listen to my grave petition,And take your ivory to Covent Garden;That they may furnish me a free admission,And you, you Lynx, you ought to out, and sallyThe Winter Theatres, or dark blind alley.The lovely Zebra, Asia's painted ass,'Stead of a den, and bed of straw possessor,Down to old Cambridge should have had a pass,To fill the office of some wise professor;Then, had he shown each antiquated quiz,His Zebra auricles were long as his.Thus had we all obtained a proper station,'Twere in one day of happiness to cruise.And I had never written my vexationAt being palac'd in the Royal Mews.The reason for which conduct I'm at loss,O, Mr. Cross, 'tay'nt you, but I am cross.I really thought thou had'st been much genteeler,Polite-o was thy grandfather, rememberThou wert a Merchant Tailor, and a stealerTo school in younger days, in cold December,Then did thy fingers, shiv'ring like a Russ,Make thee to feel—thou could'st not feel for us.At Charing Cross, the Golden Cross is thineNo longer; why, then hurry us so near it,We do not in the little tap-room dine,Where Greenwich cads and Walworth jarvies beer it,This Mews is cold to the Exchange's glow,Belle Sauvage Cross, thou'rt beau sauvage, I trow.My usage is the best, I don't deny,Thou'st fee'd the keeper, and he likes to feed us,But, then the situation I decry,But crying's useless—who the deuce will heed us?Then, reader would you listen to my wail,Come, and but see me, "I'll unfold my tail."P.T.CALCULATING CHILD

(Translated from the last number of the Revue Encyclopedique. By a Correspondent.)(For the Mirror.)A boy, seven years of age, whose name is Vincent Zuccaro, has excited the public attention at Palermo for some time past. This child, born of poor and uneducated parents, possesses an extraordinary talent for calculation; his mind seizes, as it were, by instinct, all the varied combinations of numbers, which he unravels with equal facility. The various reports which had been spread throughout the city, respecting his talents, appeared so incredible, that a public meeting of literary men was expressly convened, for the purpose of examining his pretensions. The meeting was held on the 30th of January last, at the Academy Del Buon Gusto, and consisted of upwards of four hundred persons, among whom were observed some of the most distinguished literati and influential persons of the city. Two Professors of Mathematics were stationed near the child, to prevent collusion or fraud, and to take minutes of the questions proposed, with the answers returned. A great number of questions were proposed, which Vincent Zuccaro answered with a facility that excited general admiration. We shall only extract two of the most simple, as some of the questions would be hardly intelligible to general readers:

Question 1.—A ship set sail at noon from Naples to Palermo (the distance between the two cities being 180 miles), and sailed at the rate of ten miles an hour; another ship set off at the same time, to sail from Palermo to Naples, at the rate of seven miles per hour: at what time did the ships meet each other, and what was the distance sailed by each? Vincent Zuccaro immediately replied—The first ship sailed 105 15/17 miles; the second, 74 2/17 miles. It was then observed to him, that he had only answered part of the question, and that the hour of meeting had been omitted. He then said this would be 10 10-17 hours after the time of the departure. The child had perceived that this part of the answer was implicitly contained in the former; which he also imagined the examiners perceived as well as himself, and therefore he omitted it.

Question 2.—In three successive attacks upon a town, a quarter of the assailants perished in the first attack, a fifth in the second, and a sixth in the last, when their number was reduced to 138 men. Required the original number? Answer, 360.

Q.—How did you find that number?

A.—If the number had been 60, there would eventually have remained 23; now 23 being the sixth of 138, the assailants were 6 times 60 or 360 at first.

Q.—Why did you suppose the number 60, rather than 50 or 70?

A.—Because neither 50 nor 70 are divisible by 4 or 6.

From these questions and replies, it will be readily understood that the child does not employ the ordinary artifices of mathematicians. Marquess Scriso, who was the first person to discover this singular talent, is about, with several other persons of distinction in the city, to solicit the aid of Government in the education of the child, every one being fully aware of the impropriety of subjecting him to the ordinary mode of education.

"OUT OF SEASON," OR THE BEAU'S LAMENT

(For the Mirror.)"There is no labour so great as idleness."

Heigho! what a blank is our being! ahi!For there's nobody left in the town,That's nobody fit to associate with me;Dinner's up, but my spirits are down,I can't eat or drink (how should I?) for sorrow,And the lack of some usual treat,And I surely should hang me, or marry tomorrow,Were there not a few bawls in the street.Hang! marry! said I, why I'm now drown'd in tears,Who am wont in sham pain to lose real;And could pull my own house down, about my own earsFor lack of amusements ideal;But plays, concerts, shopping, Di'ramas so bright,That enlarge the pent mind at a view,Are fled with my friends; I'm the wretchedest wightThat from devil ennui, e'er look'd blue!O horrible! horrible world! there's not e'enAn old maid in't, to ask me to tea;Not fit, or in country or town, to be seen,They have hurried off, blindly to see!Parks, houses, clubs, shops, churches, squares, deserts seem;Quite flat, Magazines and Newspapers;Ah, what shall I do? make a trial of steam,In order to banish the vapours?Shall I swallow my dinner? I can't—shall I sleep?Then I don't get away from myself!Shall I think what a beau I have once been, and weepLike a belle, that is laid on the shelf?Shall I write? shall I read? ah, yes, that will do,But an old book is terrible stuff:Boy, get the new novel, stop, reading's so new,That a book will be novel enough!M.L.B.ANCIENT HISTORY OF DRURY LANE

(For the Mirror.)The reader will most probably exclaim, "Ancient History of Drury Lane! What a farce!" A dirty lane filled with all complexions of hawkers and pedlars, licensed and unlicensed!—true incurious reader, Gay has sung

"Of Drury's mazy courts and dark abodes;"yet the topographical and theatrical loiterer may call to mind many pleasing reminiscences, although mingled with unpleasing ones:

"Who has not here a watch or snuff-box lost,Or handkerchiefs that India's shuttle boast."GAY.Stowe says, "Drury Lane, so called, for that there is a house belonging to the family of the Druries.1 This lane turneth north towards S. Giles in the field. From the south end of this lane in the high street, are divers faire buildings, hostelries, and houses for gentlemen, and men of honor, &c."

Nightingale tells us, "The west end of Wych Street was formerly ornamented by Drury House, built by Sir William Drury, an able commander in the Irish wars, in the reign of Queen Elizabeth, and who unfortunately fell in a duel with Sir John Burroughs, through a foolish quarrel about precedency. During the time of the fatal discontents of Elizabeth's favourite, the Earl of Essex, it was the place where his imprudent advisers resolved on such counsels, as terminated in the destruction of him and his adherents. In the next century it was possessed by the heroic Earl of Craven, who rebuilt it. It was lately a large brick pile, concealed by other buildings and was a public-house, bearing the sign of the Queen of Bohemia's Head, the earl's admired mistress, whose battles he fought animated by love and duty. When he could aspire to her hand, he is supposed to have succeeded, and it is said, that they were privately married; and that he built for her the fine seat at Hampstead Marshal, in the county of Berks, afterwards destroyed by fire. The services rendered by the earl to London, his native city, in particular, were exemplary. He was so indefatigable in preventing the ravages of the frequent fires of those days, that it was said his very horse smelt it out. He and Monk, Duke of Albemarle,2 heroically staid in town during the dreadful pestilence, and at the hazard of their lives preserved order in the midst of the terror of the times." The house was taken down, and the ground purchased by Mr. Philip Astley, who built there the Olympic Pavilion. In Craven Buildings there was formerly a very good portrait of the Earl of Craven in armour, with a truncheon in his hand, and mounted on his white horse. The Theatre Royal in this street, originated on the Restoration. "The king made a grant of a patent (says Pennant) for acting in what was then called the Cockpit, and the Phoenix, the actors were the king's servants, were on the establishment, and ten of them were called gentlemen of the Great Chamber, and had ten yards of scarlet cloth allowed them, with a suitable quantity of lace."

There is a curious specimen of ancient architecture at the sign of the Cock and Magpie public-house, facing Craven Buildings. Smith, in his London, says, "The late Mr. Thomas Batrich, barber, of Drury Lane, (who died in 1815, aged 85 years,) informed me that Theophilus Cibber was the author of many of the prize-fighting bills, and that he frequently attended and encouraged his favourites. It may be here observed, that Drury Lane had seldom less than seven fights on a Sunday morning, all going on at the same time on distinct spots." At present, the fights are between the apple-women and the dogberries, respecting the legal tenure of stalls:

"Bess Hoy first found it troublesome to bawl,And therefore plac'd her cherries on a stall."KING.Drury Lane will always be interesting to the theatrical loiterer, from the number of stars that have irradiated from its horizon. If the wise Solon had lived in our times, he would no doubt have felt a local attachment to this neighbourhood; for he frequented plays even in the decline of life. And Plutarch informs us, he thought plays useful to polish the manners, and instil the principles of virtue.

P.T.W.SOLUTION OF THE ENIGMATICAL EPITAPH,

(See Mirror, vol. xiv. page 214.)O! Superbe! Mors superte! Cur Superbis?Deus supernos! negat superbis vitam supernam.Proud man know this! then wherefore art thou proud?This awful doom—terrific cries aloud—Death lifts his arm! with unrelenting dart,Ready to pierce thy lofty-tow'ring heart.Why then persist? The Almighty hath deniedEternal life to all the slaves of Pride!THE SELECTOR; AND LITERARY NOTICES OF NEW WORKS

THE NEW-YEAR'S GIFT AND JUVENILE SOUVENIR FOR 1830

Edited by Mrs. Alaric WattsThe association of the line—

In wit a man, simplicity a child—is so happy as to be applicable to the Poet of all Nature. It expresses as much, if not more merit, than any single line often quoted, and its frequent repetition has probably induced us to consider the latter half—"simplicity a child"—as the peculiar talent of writing for young people, aimed at by many, yet accomplished by so few. What is it that so delights the young reader—we may say ourselves—in Robinson Crusoe3—the Shakspeare of the play-ground—but simplicity; and where, among the thousands of nursery books that have since been written, can we find its match? In childhood, youth, manhood, and old age, this is the great charm of life; and even the vitiated appetite is not unfrequently coaxed into amendment by its very delightful character when contrasted with coarser enjoyments. Metaphysicians deal out this fact to the world over and over again, and all the philosophy of Locke, Newton, and Bacon would be of little worth without it.

But this is too philosophical a strain for noticing a child's book—a little volume that is among books what a child is in human nature—"man in a small letter;" and such is Mrs. Watt's "New Year's Gift." To express all the kindly feelings which it must produce in a mind occupied as ours often is with graver matters—would be only to repeat what we said a fortnight since; and so without further premise, we will open this little casket of gems for the reader. We shall not string names together, but take a few of them. First, the "Sisters of Scio," a true story, by the author of "Constantinople in 1828," of two little Greek girls being saved from the Turks, by a good Christian. Next is "The Recall," by Mrs. Hemans:—

Music is sorrowfulSince thou wert gone;Sisters are mourning thee—Come to thine ownHark! the home voices call,Back to thy rest!Come to thy father's hall,Thy mother's breast!O'er the far blue mountains,O'er the white sea-foam,Come, thou long parted one!Back to thy home!—How appropriate is the story and its sequel; nay, almost as good as two of Mr. Farley's pantomime scenes at Christmas. "The Miller's Daughter," a tale of the French Revolution, which follows, is hardly so fit: even the mention of Robespierre and the Reign of Terror chills one's blood. "The Sights of London," is a string of "City Scenes" in verse; and "May Maxwell," and "The Broken Pitcher," are pretty ballads, by the Howitts. We are not half through the book, and can only mention "the Young Governess," a school story—"the Birds and the Beggar of Bagdad," a fairy tale—"Lady Lucy's Petition," an historiette—"the Restless Boy," by Mrs. Opie, and the "Passionate Little Girl," by Mrs. Hofland—all sparkling trifles in prose. Among the poetry is "the African Mier-Vark," or Ant-eater, by Mr. Pringle, and "the Deadly Nightshade," a sweetly touching ballad, dated from Florence; "the Vulture of the Alps" is of similar character; and we are much pleased with some lines on Birds, by Barry Cornwall, one set of which we copy, the best prose papers being too long for extract:

TO A WOUNDED SINGING BIRD

Poor singer! hath the fowler's gun,Or the sharp winter, done thee harm?We'll lay thee gently in the sun,And breathe on thee, and keep thee warm;Perhaps some human kindness stillMay make amends for human ill.We'll take thee in, and nurse thee well,And save thee from the winter wild,Till summer fall on field and fell,And thou shalt be our feathered child,And tell us all thy pain and wrongWhen thou again canst speak in song.Fear not, nor tremble, little bird,—We'll use thee kindly now,And sure there's in a friendly wordAn accent even thou shouldst know;For kindness which the heart doth teach,Disdaineth all peculiar speech.'Tis common to the bird, and brute,To fallen man, to angel bright,And sweeter 'tis than lonely luteHeard in the air at night—Divine and universal toungue,Whether by bird or spirit sung!But hark! is that a sound we hearCome chirping from its throat,—Faint—short—but weak, and very clear,And like a little grateful note?Another? ha—look where it lies,It shivers—gasps—is still,—it dies!'Tis dead,—'tis dead! and all our careIs useless. Now, in vainThe mother's woe doth pierce the air,Calling her nestling bird again!All's vain:—the singer's heart is cold,Its eye is dim,—its fortune told!A versification of a story in Mrs. Barbauld's "Evenings at home," by Sneyd Edgeworth, Esq. deserves favourable mention; even the names will tempt the reader.

There are eleven plates; the frontispiece, "Little Flora," from Boaden, and engraved by Edwards, is a sweet production; and the figures in "the Broken Pitcher," from Gainsborough,4 are well executed by H. Robinson. To conclude, we cordially recommend this little volume to such purchasers as wish to combine simplicity with talent, and the several beauties of picture and print in their "New Year's Gift," for 1830.

EDIE OCHILTREE

From the New Edition of "The Antiquary."Of the "blue gowns," or king's bedesmen, from whom the character of Edie Ochiltree was drawn, after giving an account from Martin's "Reliquiae Divi Sancti Andrae," of an order of beggars in Scotland, supposed to have descended from the ancient bards, and existing in Scotland in the seventeenth century, but now extinct, Sir Walter Scott says:—

"The old remembered beggar, even in my own time, like the Baccoch, or travelling cripple of Ireland, was expected to merit his quarters by something beyond an exposition of his distresses. He was often a talkative, facetious fellow, prompt at repartee, and not withheld from exercising his powers that way by any respect of persons, his patched cloak giving him the privilege of the ancient jester. To be a gude crack, that is, to possess talents for conversation, was essential to the trade of a 'puir body' of the more esteemed class; and Burns, who delighted in the amusement their discourse afforded, seems to have looked forward with gloomy firmness to the possibility of himself becoming one day or other a member of their itinerant society. In his poetical works, it is alluded to so often, as perhaps to indicate that he considered the consummation as not utterly impossible. Thus, in the fine dedication of his works to Gavin Hamilton, he says—

"And when I downa yoke a naig,Then, Lord be thankit, I can beg."Again, in his Epistle to Davie, a brother poet, he states, that in their closing career—

"The last o't, the warst o't,Is only just to beg."And after having remarked, that

"To lie in kilns and barns at e'en,When banes are crazed and blude is thin,Is doubtless great distress;"the bard reckons up, with true poetical spirit, the free enjoyment of the beauties of nature, which might counterbalance the hardship and uncertainty of the life even of a mendicant. In one of his prose letters, to which I have lost the reference, he details this idea yet more seriously, and dwells upon it, as not ill adapted to his habits and powers.

"As the life of a Scottish mendicant of the eighteenth century, seems to have been contemplated without much horror by Robert Burns, the author can hardly have erred in giving to Edie Ochiltree something of poetical character and personal dignity, above the more abject of his miserable calling. The class had, in fact, some privileges. A lodging, such as it was, was readily granted to them in some of the outhouses, and the usual awmous (alms) of a handful of meal (called a gowpen) was scarce denied by the poorest cottager. The mendicant disposed of these, according to their different quality, in various bags around his person, and thus carried about with him the principal part of his sustenance, which he literally received for the asking. At the houses of the gentry, his cheer was mended by scraps of broken meat, and perhaps a Scottish 'twal-penny,' or English penny, which was expended in snuff or whisky. In fact, these indolent peripatetics suffered much less real hardship and want of food, than the poor peasants from whom they received alms.

"If, in addition to his personal qualifications, the mendicant chanced to be a King's Bedesman, or Blue Gown, he belonged, in virtue thereof, to the aristocracy of his order, and was esteemed a person of great importance."