Полная версия:

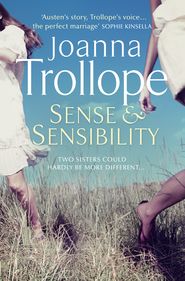

Sense & Sensibility

Belle smiled at Sir John.

‘Elinor’s studying architecture. She draws beautifully.’

He smiled back at her. ‘I remember Henry saying you did, too. You’ll be in your element at Barton, drawing and painting away.’

‘I did figures, mostly, but I’m sure I could—’

‘And Elinor’, Marianne said loudly, ‘draws buildings. Where can she study buildings in Devon?’

‘Darling. Don’t, darling. Don’t be rude.’

John Middleton beamed again at Marianne. ‘She’s not rude. She’s refreshing. I like refreshing. My kids will adore her; they love anyone out of the ordinary. Four of them. Enough energy to power your average city, between them.’ He closed his laptop and looked up at Belle. ‘Well,’ he said, ‘Well. Can I take it that you and the girls will come and live at Barton Cottage for what I promise you will be a very modest rent?’

Margaret took her fingers out of her ears and opened her eyes. She flung her arms wide in a gesture of despair. ‘What about all my friends?’ she said.

‘I wonder’, Belle said from the doorway, ‘if I could trouble you for a moment?’

Both Fanny and John Dashwood, who were watching the evening news on television with glasses in their hands, gave a little jump in their chairs.

‘Belle!’ John Dashwood said, with surprise rather than pleasure.

He leaned forward and reduced the volume on the television, although he didn’t turn it off altogether. Fanny remained where she was, holding her wine glass. John stood up slowly. ‘Have a drink,’ he said automatically, gesturing vaguely towards the bottle plainly visible on a silver tray on the coffee table in front of them.

‘I’m sure’, Fanny said, ‘that she won’t be staying that long.’

Belle smiled at her. She advanced into the room far enough to give herself authority, but not so far that she couldn’t make a quick escape. ‘Quite right, Fanny. I will be two minutes. We had a visitor this afternoon.’

Fanny continued to regard her wine glass. She said to it, ‘I wondered when you would see fit to mention that to me.’

Belle smiled broadly at John. ‘Would it be an awful nuisance to turn the television off?’

John glanced at Fanny. She made an impatient little gesture of dismissal. He picked up the remote again and aimed it at the screen.

‘Thank you,’ Belle said. She was determined to keep smiling. She folded her hands lightly in front of her. ‘The thing is, that we won’t be troubling you here at Norland much longer. We’ve been offered a house. By a relation of mine.’

John looked truly startled. ‘Good heavens.’

Fanny said smoothly, ‘But not too far from here, I hope?’

‘Actually …’ Belle said, and stopped, savouring the moment.

‘Actually what?’

‘We are going to Devon,’ Belle said with satisfaction.

‘Devon!’

‘Near Exeter. A house on an estate which is, I gather, just a fraction larger than this one. It belongs to my cousin. My cousin Sir John Middleton.’

John said, almost inaudibly, ‘My cousin, I believe. A Dashwood cousin.’

Belle took no notice. She looked directly, smilingly, at Fanny. ‘So we’ll be out of your hair by the end of the month. As soon as we can sort a school for Margaret and all that.’

‘But I was going to help you find a house!’ John said aggrievedly.

‘So sweet of you, but in the end the house came to us.’

‘So lucky,’ Fanny said.

‘Oh, I agree. So lucky.’

‘It’s too bad,’ John exclaimed.

‘What is?’

‘It’s too bad of you to make all these arrangements without consulting me.’

‘But you didn’t want me to consult you,’ Belle said.

Fanny said clearly, ‘Sweetness, you’ve given them all somewhere to live all summer, rent free, and the run of the kitchen gardens, after all.’

John glanced at her. He said with relief, ‘So I have.’

‘There we are,’ Belle said brightly. ‘All settled. You let us stay on in our own home for a while and now we’ve found another one to go to! Perfect. I’ve taken Barton Cottage for a year and, of course, it would be lovely to see you there whenever you are down that way.’

Fanny looked out of the window. ‘I never go to Devon,’ she said.

Belle paused in the doorway. ‘No,’ she said, ‘I thought not. But maybe you’ll break the habit of a lifetime. It’s odd, really, that you never went to see Edward all the time he was in Plymouth, don’t you think?’

Fanny’s head snapped back round. ‘Edward! Why mention Edward?’

Belle was almost out of the door. ‘Oh, Edward,’ she said airily. ‘Dear Edward. So affectionate. He’s going to come to Barton. I made a special point of asking him to come and see us in the cottage. And he said he’d love to.’

And then she reached for the handle and closed the door behind her with a small but triumphant bang.

4

‘Marianne,’ Elinor said, ‘will you please put that guitar down and come and help us?’

Marianne was in her favourite playing chair by the window in her bedroom, her right foot on a small pile of books – a French dictionary and two volumes of Shakespeare’s history plays came to just the right height – and the guitar resting comfortably across her thigh. She was playing a song of Taylor Swift’s that she had played a good deal since Dad died, even though – or maybe even because – everyone had told her that a player at her level could surely express themselves better with something more serious. It was called ‘Teardrops on My Guitar’, and to Elinor’s mind, it was mawkish.

‘Oh, M, please.’

Marianne played determinedly on to the end of a verse. She said, when she’d finished, ‘I know you hate that song.’

‘I don’t hate it …’

‘It isn’t much of a song. I know that. It isn’t hard to play. But it suits me. It suits how I feel.’

Elinor said, ‘We’re packing books. You can’t imagine how many books there are.’

‘I thought the cottage was furnished?’

‘It is. But not with books and pictures and things. We could get through it so much more quickly if you just came and helped a bit.’

Marianne raised her head to look out of the window. She folded both arms embracingly around her guitar. She said, ‘Can you imagine being away from here?’

Elinor said tiredly, ‘We’ve been through all that.’

‘Look at those trees. Look at them. And the lake. I’ve done all my practice by this window, looking out at that view. I’ve played the guitar in this room for ten years, Ellie, ten years.’ She looked down at the guitar. ‘Dad gave me my guitar in this room.’

‘I remember.’

‘When I got grade five.’

‘Yes.’

‘He did all the research, and everything. I remember him saying it had to have a cedar top and rosewood sides and an ebony fingerboard, a proper, classical, Spanish guitar. He was so excited.’

Elinor came further into the room. She said soothingly, ‘It’s coming with us, M, you’ll have your guitar.’

Marianne said suddenly, ‘Fanny—’ and stopped.

‘Fanny? What about her?’

Marianne looked at her. ‘Yesterday. Fanny asked me what the guitar had cost.’

‘She didn’t! What did you say to her?’

‘I told her,’ Marianne said, ‘I said I couldn’t remember exactly, I thought maybe a bit more than a thousand, and she said who paid for it.’

‘The cheek!’ Elinor exclaimed.

‘Well, I was caught on the hop, wasn’t I, because she then said did Dad pay for it, and I said it was a joint present for getting grade five from Dad and Uncle Henry, and she said, Well, that really means it belongs to Norland, doesn’t it, if Uncle Henry paid for some of it, and not you.’

Elinor sat down abruptly on the end of Marianne’s bed. She said, ‘You couldn’t make Fanny up, could you?’

Marianne laid her cheek on the guitar’s rosewood flank. ‘I put it under my bed last night. I’m not letting it out of my sight.’

‘And you still want to stay here? Even if it meant living with Fanny?’

Marianne lifted her head and then stood up, adjusting the guitar so that she was holding it by the neck. She said, ‘It’s the place, Ellie. It’s the trees and the light and the way it makes me feel. I just can’t imagine anywhere else feeling like home. I’m terrified that nowhere else ever will be home. Even with Fanny, I just – just belong, at Norland.’

Elinor sighed. Marianne had not only inherited their father’s asthma, but also his propensity for depression. It was something they all had learned to accept, and to live with: the mood swings and the proclivity for inertia and despair. Elinor thought about what lay ahead, about the enormity of this move to such a completely unknown environment and society and wondered, slightly desperately, if she could manage to accommodate a bout of Marianne’s depression as well as their mother’s volatility and Margaret’s appalled reaction at having to leave behind every single person she had ever known or been at school with in her whole, whole life.

‘Please,’ Elinor said again. ‘Please don’t give up before we’ve even got there.’

‘I’ll try,’ Marianne said in a small voice.

‘I can’t manage all of you hating this idea—’

‘Ma doesn’t. It was Ma who bounced us all into this.’

‘Ma’s on a high at the moment because she got one across Fanny. It won’t last.’

Marianne looked at her sister. ‘I’ll try,’ she said again, ‘I really will.’

‘There’ll be other trees—’

‘Don’t.’

‘And valleys. And jolly Sir John.’

Marianne gave a tiny shudder. ‘Suppose they’re the only people we know?’

‘They won’t be.’

‘Maybe’, Marianne said, ‘Edward will come.’

Elinor said nothing. She got off the bed and made purposefully for the door.

‘Ellie?’

‘Yes.’

‘Have you heard from Edward?’

There was a tiny pause.

‘He hasn’t rung,’ Elinor said.

‘Have you seen him on Facebook?’

In the doorway, Elinor turned. ‘I haven’t looked,’ she said.

Marianne bent to lay her guitar down on her bed, like a child. ‘He likes you, Ellie.’

There was another little pause. ‘I – know he does.’

‘I mean,’ Marianne said, ‘he really likes you. Seriously.’

‘But he’s caught—’

‘It’s pathetic, these days, to be still under your mother’s thumb. Like he is.’

Elinor said quite fiercely, ‘She neglected him. And spoiled the others. She isn’t at all fair.’

Marianne came and stood close to her sister. ‘Oh, good,’ she said. ‘Standing up for Edward. Good sign.’

Elinor looked at her sister with sudden directness. ‘I can’t think about that.’

‘Can’t you?’

‘No,’ Elinor said. ‘Today I am thinking about packing up books so I don’t have to think about giving up my degree.’

Marianne looked stricken. ‘Oh, Ellie, I didn’t think …’

‘No. Nobody does. I know I’d only got a year to go, but I had to ring my year co-ordinator and tell him I wouldn’t be back this term.’ She broke off, and then she said, ‘We were going to concentrate on surveying this term. And model-making. I was, he said, possibly the best at technical drawing in my year. He said – oh God, it doesn’t matter what he said.’

Marianne put her arms round her sister. ‘Oh, Ellie.’

‘It’s OK.’

‘It isn’t, it isn’t, it’s so unfair.’

‘Maybe’, Elinor said, standing still in Marianne’s embrace, ‘I can pick it up again later.’

‘In Exeter? Could you join a course in Exeter?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘Have you told Ma?

Elinor sighed. ‘Sort of. I don’t want to burden her.’

‘Please think about telling her properly. Please think about finishing your course in Exeter.’

Elinor sighed. She gave Marianne a quick hug, and detached herself. ‘I’ll try. In due course, I’ll try. Right now … Right now I can’t think about anything except getting us all settled in Devon without losing our minds or our money.’ She paused and then she said, ‘Please come and help with these books?’

Sir John sent the handyman from Barton Park to Norland, with Sir John’s own Range Rover, to drive the Dashwoods down to Devon. He also organised a removal company from Exeter to come and collect their books and pictures, and their china and glass, and Belle had the exquisite satisfaction of seeing the Provençal plates disappearing into paper-filled boxes, and in then labelling those boxes with a bold black marker pen so that Fanny, monitoring the whole packing-up procedure, could not fail to observe the china’s departure.

John Dashwood was very uneasy around the whole process. When he returned each day from the notional job of running the Ferrarses’ commercial property empire – he was regarded as an inevitable and unwelcome nuisance by the man who actually did the work – he hovered in Belle’s sitting room or kitchen, mournfully reciting the expenses that made Norland such an exhausting drain upon his wallet and energies, and pointing out how lucky Belle was to be exchanging life at Norland for one of such carefree simplicity and frugality in Devon. Only once did Belle grow so exasperated by his perpetual litany of complaints that she was driven to point out quite sharply that the promise of generosity made in that room at Haywards Heath Hospital had never actually been adhered to. John Dashwood had been deeply wounded by her accusation that he had been other than both honourable and generous, and said so. ‘It’s too bad of you, Belle. It really is. You and the girls have had absolutely the run of the house and garden since Henry died, the complete run. It’s been really inconvenient for Fanny, having you here and having to put all her decorating plans on hold, but of course she’s been angelic about that. As she has about everything. I sometimes wonder, Belle, if Henry didn’t spoil you, I really do. You don’t seem to have the first idea about recognising or acknowledging generosity. I’m really quite shocked. I just hope poor old John Middleton knows what he’s in for, trying to help someone who appears not to have the first idea of even how to say thank you.’ He’d peered at her, cradling his whisky and soda. ‘Just a “thank you, John” would be nice. Don’t you think? It’s all I’m asking, after everything you’ve been given. Just a thank you, Belle.’

It was a relief, in the end, to see Sir John’s car. Belle climbed in beside young Thomas, the handyman, who had put on his new jeans in honour of this important commission from his employer, and the girls got into the back seat behind her, Margaret clutching her iPod, her childhood Nintendo DS and her pocketbook laptop, as if they represented her only frail remaining link to civilised or social life as she knew it. Behind the girls Thomas stacked their suitcases and, on top of that, Marianne’s guitar case, which she had held in her arms all the time she was saying goodbye to John and Fanny. Fanny had been holding Harry’s hand, as if he were a trump card that she needed to flourish at the final moment of victory. In the hand not gripped by his mother, Harry was clutching a giant American-style cookie which seemed to absorb too much of his attention for there to be any to spare for his cousins’ departure. Elinor had knelt in front of him, and smiled. ‘Bye, bye, Harry.’

He regarded her, chewing. She leaned forward and kissed his cheek. ‘You smell of biscuit.’

He frowned.

‘It’s a cookie,’ he said reprovingly, and wedged it in his mouth again.

‘Poor little boy,’ Elinor said, later, in the car.

‘Is he?’

‘Course he is. Having Fanny for a mother …’

Belle turned in her seat. She said, rolling her eyes slightly in the direction of Thomas, ‘Let’s not talk about Fanny.’

‘She didn’t wave,’ Marianne said. She gazed out of the window, as if devouring what she saw as it sped past her.

‘No.’

‘She turned her face so that I kind of got her ear when I kissed her.’

‘Yuck, having to kiss her at all …’

‘She was pretty well smirking!’

‘She’s horrible.’

‘She’s over,’ Belle said firmly. ‘Over.’ Then she turned and smiled brightly at Thomas, who was driving with elaborate professionalism, and exclaimed, almost theatrically, ‘And we are starting a new life, in Devon!’

In the bright, small kitchen at Barton Cottage, with its immediate view of a rotary washing line planted in a square of paving, Elinor surveyed the unpacked boxes. She had said that she would sort the kitchen not just out of altruism, but also so that she could have time to herself, time to try and retrieve her mind and spirit, neither of which had yet made the journey with her body, from Norland to Barton.

It had been quite a good journey for the first few hours. Everyone was slightly hysterical with the immediate relief of escaping the pressure of living in a house with other people who so openly wanted them gone, but then Marianne had gone suddenly very quiet and then very pale and when Elinor, trained by long practice to be alert to her sister’s symptoms, asked if she was OK, she had begun to wheeze and gasp alarmingly, and Belle had ordered Thomas, in a voice urgent with panic, to stop the car.

They had tumbled out on to the verge of the A31 somewhere west of Southampton, and Elinor had been intensely grateful to Thomas, who quietly established himself beside Marianne as they all crouched on the tired grass by a litter bin in a parking place, and supported her while Elinor held her blue inhaler to her mouth and talked to her steadily and quietly, as she had so often done before.

‘Poor darling,’ Belle said, over and over. ‘Poor darling. It’ll be the stress of leaving Norland.’

‘Or the dogs, miss,’ Thomas said matter-of-factly.

‘What dogs? There aren’t any dogs.’

‘In the car,’ Thomas said. He was watching Marianne with a practical eye that was infinitely comforting to Elinor. ‘Sir John’s dogs is always in the car. Doesn’t matter how often we hoover it, we never get all the hairs out. My nan had asthma. Couldn’t even have a budgie in the house, never mind dogs and cats.’

‘Sorry,’ Marianne said, between breaths. ‘Sorry.’

‘Never be sorry …’

‘Just say, a bit earlier, next time.’

‘It won’t be an omen, will it?’

Margaret said, ‘We did omens at school and the Greeks thought—’

‘Shut up, Mags.’

‘But—’

‘We’ll put you in the front seat,’ Thomas said to Marianne, ‘with the window open.’

She nodded. Elinor looked at him. He was wearing the expression of fierce protectiveness that so many men seemed to adopt round Marianne. Solicitously, with Elinor’s assistance, he lifted Marianne to her feet.

‘Thank you,’ Elinor said.

He began to guide Marianne back to the car, his arm round her shoulders. ‘Nothing to thank me for,’ he said, and his voice was proud.

The rest of the journey had passed almost in silence. Thomas drove soberly and steadily, with Marianne leaning her head back in the seat beside him, her face turned towards the open window, her inhaler on her lap. Behind them, Elinor gripped Margaret’s hand and Belle sat with her eyes closed (in a way that suggested crowding memories rather than repose) as Hampshire gave way to Dorset, and Dorset, in its turn and after seemingly endless hours, to Devon.

It was only in the last five miles or so, as the countryside grew increasingly beautiful and spectacular, that they began to rouse themselves from the aftermath of shock and exclaim at what they were passing.

‘Oh, look.’

‘This is amazing!’

‘Gosh, Thomas, is Barton going to be this good?’

It was. They left the road and turned in between stone gateposts crowned with urns that heralded a series of drives curving away around a smooth hillside crowned with trees. There were freshly painted signs planted alongside the drives, indicating the directions to the main house, to the offices, to visitors’ parking and, with a right-angled arrow, to Barton Cottage. And there, after a further few minutes, it was, as raw and new looking as it had been on Sir John’s laptop, but set on a pleasing slope, with woods climbing up behind it, and the forked valleys falling away dramatically in front. They had gasped when they saw it, as much for its astonishing situation as for its uncompromising banality of design.

Thomas had looked at it with satisfaction.

‘We never thought he’d get planning permission,’ he said. ‘We all bet he wouldn’t. But he managed to prove there’d been a shepherd’s cottage up there once, so there’d been a residence. If he wants something, he doesn’t give up. That’s Sir John.’

Sir John had left wine and a note of welcome in the kitchen, and a basket of logs by the sitting-room fireplace. Someone had also put milk and bread and eggs in the fridge, and a bowl of apples on the new yellow-wood kitchen table, and Margaret reported, after inspecting the bathroom, that there was also a full roll of toilet paper and a new shower curtain, printed with goldfish. Elinor could not think why, confronted both with the kindness of almost strangers, and a practical little house in a magnificent place, she should feel like doing nothing so much as taking herself off somewhere private and quiet, to cry. But she did – and there was no immediate opportunity, what with Marianne needing to be assisted into the house, and Belle and Margaret exclaiming at the advantages (Margaret) and disadvantages (Belle) of their new home, to indulge herself. The luxury of being alone and able to look at and begin to arrange her thoughts would have, as it so often did, to wait.

And now, here was her chance, by herself in the kitchen, with unpacked boxes of saucepans and plates. It was comical, really, the way she’d ended up with unpacking all the practical stuff, while the others, ably and eagerly assisted by Thomas, decided where the pictures should hang and which window gave on to the right prospect to be conducive to guitar practice. Margaret had found a tree outside where she could get five whole signal bars on her mobile phone, if she climbed up into the lowest branches, and Thomas had immediately said that he would make her a tree house, just as he had agreed with Belle that the cottage could be easily improved by extending the main sitting room into a conservatory on the southern side. He had said he would bring brochures. Elinor had said quietly, ‘What about me?’

Belle went on looking at the space where the conservatory might stand. ‘What about you, darling?’

‘Well,’ Elinor said, ‘most architects get their first break designing extensions for family houses. Even Richard Rogers—’

Belle gave her a quick glance. ‘But you’re not qualified, darling.’

‘I nearly am. I’m qualified enough.’

Belle smiled, but not at Elinor. ‘I don’t think so, darling. I’d be happier with professionals who do thousands of conservatories a year.’

Elinor closed her eyes and counted slowly to ten. Then she opened them and said, in as level a voice as she could manage, ‘There’s another thing.’

Belle was gazing at the view again. ‘Oh?’

‘Yes,’ Elinor said, more firmly. ‘Yes. What about the money?’

She put two frying pans down on the kitchen table, now, beside three mugs and a handful of wooden spoons, which had been wrapped, in the universal manner of removal men, as solicitously in new white paper as if they had been Meissen shepherdesses. Money was haunting her. Money to buy and run a car – how else was Margaret to get to her new school in Exeter? Money to pay the rent, money for electricity and water, money to pay for food and clothes and even tiny amounts of fun, when all they had in the world was, when invested, going to produce under seven hundred pounds a month, or less than two hundred pounds a week. Which was, she calculated, banging Belle’s battered old stockpot down beside the frying pans, not quite thirty pounds a day. For four women with laughable earning power, one of whom is still at school, one is unused to work, and one is both physically unfit and as yet unqualified to work. Which leaves me! Me, Elinor Dashwood, who has been living in the cloud cuckoo land of Norland and idiotic, impractical dreams of architecture. She straightened up and looked round the kitchen. The prospect – bright new units overlaid with a chaos of unarranged shabby old possessions – was sobering. It was also, if she didn’t keep the tightest of grip on herself, frightening. She was not equipped for this. None of them were. They had fled to Devon on an impulse, reacting against the grief and rejection they had been through, surrendering to the first hand held out to them without considering the true extent or consequences of that surrender.