Полная версия:

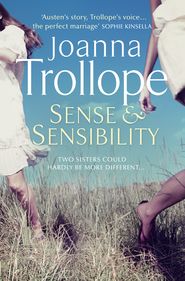

Sense & Sensibility

‘But’, Elinor said quietly, ‘that’s what Fanny wants. She wants a sort of showcase. And she’ll get it. We heard her. She’s got John just where she wants him. And, because of him, she’s got Norland. She can do what she likes with it. And she will.’

An uneasy forced bonhomie hung over the house for days afterwards until yesterday, when John had come into their kitchen rather defiantly and put a bottle of supermarket white wine down on the table with the kind of flourish only champagne would have merited and announced that actually, as it turned out, all things being considered, and after much thought and discussion and many sleepless nights, especially on Fanny’s part, her being so sensitive and affectionate a person, they had come to the conclusion that they – he, Fanny, Harry and the live-in nanny – were going to need Norland to themselves.

There’d been a stunned silence. Then Margaret said loudly, ‘All fifteen bedrooms?’

John had nodded gravely. ‘Oh yes.’

‘But why – how—’

‘Fanny has ideas of running Norland as a business, you see. An upmarket bed and breakfast. Or something. To help pay for the upkeep, which will be’ – he rolled his eyes to the ceiling – ‘unending. Paying to keep Norland going will need a bottomless pit of money.’

Belle gazed at him, her eyes enormous. ‘But what about us?’

‘I’ll help you find somewhere.’

‘Near?’

‘It has to be near!’ Marianne cried, almost gasping. ‘It has to, it has to, I can’t live away from here, I can’t—’

Elinor took her sister’s nearest hand and gripped it.

‘A cottage,’ John suggested.

‘A cottage!’

‘There are some adorable Sussex cottages.’

‘But they’ll need paying for,’ Belle said despairingly, ‘and I haven’t a bean.’

John looked at her. He seemed a little more collected. ‘Yes, you have.’

‘No,’ Belle said. ‘No.’ She felt for a chairback and held on to it. ‘We were going to have plans. To make some money to pay for living here. We had schemes for the house and estate, maybe using it as a wedding venue or something, after Uncle Henry died, but there wasn’t time, there was only a year, before – before …’

Elinor moved to stand beside her mother.

‘There’s the legacies,’ John said.

Belle flapped a hand, as though swatting away a fly. ‘Oh, those …’

‘Two hundred thousand pounds is not nothing, my dear Belle. Two hundred thousand is a considerable sum of money.’

‘For four women! For four women to live on forever! Four women without even a roof over their heads?’

John looked stricken for a moment and then rallied. He indicated the bottle on the table. ‘I brought you some wine.’

Margaret inspected the bottle. She said to no one in particular, ‘I don’t expect we’ll even cook with that.’

‘Shush,’ Elinor said, automatically.

Belle surveyed her stepson. ‘You promised your father.’

John looked back at her. ‘I promised I’d look after you. I will. I’ll help you find a house to rent.’

‘Too kind,’ Marianne said fiercely.

‘The interest on—’

‘Interest rates are hopeless, John.’

‘I’m amazed you know about such things.’

‘And I’m amazed at your blithe breaking of sacred promises.’

Elinor put a hand on her mother’s arm. She said to her brother, ‘Please.’ Then she said, in a lower tone, ‘We’ll find a way.’

John looked relieved. ‘That’s more like it. Good girl.’

Marianne shouted suddenly, ‘You are really wicked, do you hear me? Wicked! What’s the word, what is it, the Shakespeare word? It’s – it’s – yes, John, yes, you are perfidious.’

There was a brief, horrified silence. Belle put a hand out towards Marianne and Elinor was afraid they’d put their arms round each other, as they often did, for solidarity, in extravagant reaction.

She said to John, ‘I think you had better go.’

He nodded thankfully, and took a step back.

‘She’ll be looking for you,’ Margaret said. ‘Has she got a dog whistle she can blow to get you to come running?’

Marianne stopped looking tragic and gave a snort of laughter. So, a second later, did Belle. John glanced at them both and then looked past them at the Welsh dresser where all the plates were displayed, the pretty, scallop-edged plates that Henry and Belle had collected from Provençal holidays over the years, and lovingly brought back, two or three at a time.

John moved towards the door. With his hand on the handle, he turned and briefly indicated the dresser. ‘Fanny adores those plates, you know.’

And now, only a day later, here they were, grouped round the table yet again, exhausted by a further calamity, by rage at Fanny’s malevolence and John’s feebleness, terrified at the prospect of a future in which they did not even know where they were going to lay their heads, let alone how they were going to pay for the privilege of laying them anywhere.

‘I will of course be qualified in a year,’ Elinor said.

Belle gave her a tired smile. ‘Darling, what use will that be? You draw beautifully but how many architects are unemployed right now?’

‘Thank you, Ma.’

Marianne put a hand on Elinor’s. ‘She’s right. You do draw beautifully.’

Elinor tried to smile at her sister. She said, bravely, ‘She’s also right that there are no jobs for architects, especially newly qualified ones.’ She looked at her mother. ‘Could you get a teaching job again?’

Belle flung her hands wide. ‘Darling, it’s been forever!’

‘This is extreme, Ma.’

Marianne said to Margaret, ‘You’ll have to go to state school.’

Margaret’s face froze. ‘I won’t.’

‘You will.’

‘Mags, you may just have to—’

‘I won’t!’ Margaret shouted.

She ripped her earphones out of her ears and stamped to the window, standing there with her back to the room and her shoulders hunched. Then her shoulders abruptly relaxed. ‘Hey!’ she said, in quite a different voice.

Elinor half rose. ‘Hey what?’

Margaret didn’t turn. Instead she leaned out of the window and began to wave furiously. ‘Edward!’ she shouted. ‘Edward!’ And then she turned back long enough to say, unnecessarily, over her shoulder, ‘Edward’s coming!’

2

However detestable Fanny had made herself since she arrived at Norland, all the Dashwoods were agreed that she had one redeeming attribute, which was the possession of her brother Edward.

He had arrived at the Park soon after his sister moved in, and everyone had initially assumed that this tallish, darkish, diffident young man – so unlike his dangerous little dynamo of a sister – had come to admire the place and the situation that had fallen so magnificently into Fanny’s lap. But after only a day or so, it became plain to the Dashwoods that the perpetual, slightly needy presence of Edward in their kitchen was certainly because he liked it there, and felt comfortable, but also because he had nowhere much else to go, and nothing much else to occupy himself with. He was even, it appeared, perfectly prepared to confess to being at a directionless loose end.

‘I’m a bit of a failure, I’m afraid,’ he said quite soon after his arrival. He was sitting on the edge of the kitchen table, his hair flopping in his eyes, pushing runner beans through a slicer, as instructed by Belle.

‘Oh no,’ Belle said at once, and warmly, ‘I’m sure you aren’t. I’m sure you’re just not very good at self-promotion.’

Edward stopped slicing to extract a large, mottled pink bean that had jammed the blades. He said, slightly challengingly, ‘Well, I was thrown out of Eton.’

‘Were you?’ they all said.

Margaret took one earphone out. She said, with real interest, ‘What did you do?’

‘I was lookout for some up-to-no-good people.’

‘What people? Real bad guys?’

‘Other boys.’

Margaret leaned closer. She said, conspiratorially, ‘Druggies?’

Edward grinned at his beans. ‘Sort of.’

‘Did you take any?’

‘Shut up, Mags,’ Elinor said from the far side of the room.

Edward looked up at her for a moment, with a look she would have interpreted as pure gratitude if she thought she’d done anything to be thanked for, and then he said, ‘No, Mags. I didn’t even have the guts to join in. I was lookout for the others, and I messed up that, too, big time, and we were all expelled. Mum has never forgiven me. Not to this day.’

Belle patted his hand. ‘I’m sure she has.’

Edward said, ‘You don’t know my mother.’

‘I think’, said Marianne from the window seat where she was curled up, reading, ‘that it’s brilliant to be expelled. Especially from anywhere as utterly conventional as Eton.’

‘But maybe,’ Elinor said quietly, ‘it isn’t very convenient.’

Edward looked at her intently again. He said, ‘I was sent to a crammer instead. In disgrace. In Plymouth.’

‘My goodness,’ Belle said, ‘that was drastic. Plymouth!’

Margaret put her earphone back in. The conversation had gone back to boring.

Elinor said encouragingly, ‘So you got all your A levels and things?’

‘Sort of,’ Edward said. ‘Not very well. I did a lot of – messing around. I wish I hadn’t. I wish I’d paid more attention. I’d really apply myself to it now, but it’s too late.’

‘It’s never too late!’ Belle declared.

Edward put the bean slicer down. He said, again to Elinor, as if she would understand him better than anyone, ‘Mum wants me to go and work for an MP.’

‘Does she?’

‘Or do a law degree and read for the Bar. She wants me to do something – something …’

‘Showy,’ Elinor said.

He smiled at her again. ‘Exactly.’

‘When what you want to do,’ Belle said, picking up the slicer again and putting it back gently into his hand, ‘is really …?’

Edward selected another bean. ‘I want to do community work of some kind. I know it sounds a bit wet, but I don’t want houses and cars and money and all the stuff my family seems so keen on. My brother Robert seems to be able to get away with anything just because he isn’t the eldest. My mother – well, it’s weird. Robert’s a kind of upmarket party planner, huge rich parties in London, the sort of thing I hate, and my mother turns a completely blind eye to that hardly being a career of distinction. But when it comes to me, she goes on and on about visibility and money and power. She doesn’t even seem to look at the kind of person I am. I just want to do something quiet and sort of – sort of …’

‘Helpful?’ Elinor said.

Edward got off the table and turned so that he could look at her with pure undiluted appreciation. ‘Yes,’ he said with emphasis.

Later that night, jostling in front of the bathroom mirror with their toothbrushes and dental floss, Marianne said to Elinor, ‘He likes you.’

Elinor spat a mouthful of toothpaste foam into the basin. ‘No, he doesn’t. He just likes being around us all, because Ma’s cosy with him and we don’t pick on him and tell him to smarten up and sharpen up all the time, like Fanny does.’

Marianne took a length of floss out of her mouth. ‘Ellie, he likes us all. But he likes you in particular.’

Elinor didn’t reply. She began to brush her hair vigorously, upside down, to forestall further conversation.

Marianne reangled the floss across her lower jaw. Round it she said indistinctly, ‘D’you like him?’

‘Can’t hear you.’

‘Yes, you can. Do you, Elinor Dashwood, picky spinster of this parish for whom no man so far seems to be remotely good enough, fancy this very appealing basket case called Edward Ferrars?’

Elinor stood upright and pushed the hair off her face. ‘No.’

‘Liar.’

There was a pause.

‘Well, a bit,’ Elinor said.

Marianne leaned forward and peered into the mirror. ‘He’s perfect for you, Ellie. You’re such a missionary, you’d have to have someone to rescue. Ed is ripe for rescue. And he’s the sweetest guy.’

‘I’m not interested. The last thing I want right now is anyone else who needs sorting.’

‘Bollocks,’ Marianne said.

‘It’s not—’

‘He couldn’t take his eyes off you tonight. You only had to say the dullest thing and he was all over you, like a Labrador puppy.’

‘Stop it.’

‘But it’s lovely, Ellie! It’s lovely, in the midst of everything that’s so awful, to have Edward thinking you’re wonderful.’

Elinor began to smooth her hair back into a ponytail, severely. ‘It’s all wrong, M. It’s all wrong at the moment with all this uncertainty and worrying about money, and where we’ll go and everything. It’s all wrong to be thinking about whether I like Edward.’

Marianne turned to her sister, suddenly grinning. ‘Tell you what …’

‘What?’

‘Wouldn’t it just completely piss off Fanny if you and Ed got together?’

The next day, Edward borrowed Fanny’s car and asked Elinor to go to Brighton with him.

‘Does she know?’ Elinor said.

He smiled at her. He had beautiful teeth, she noticed, even if nobody could exactly call him handsome. ‘Does who know what?’

‘Does – does Fanny know you are going to Brighton?’

‘Oh yes,’ Edward said easily, ‘I’ve got a huge list of things to pick up for her: bath taps and theatre tickets and wallpaper samples from—’

‘I didn’t mean that,’ Elinor said. ‘I meant, does Fanny know you were going to ask me to go with you?’

‘No,’ Edward said. ‘And she needn’t. I have her great bus for the day, I have her shopping list, and nothing else is any of her business.’

Elinor looked doubtful.

‘He’s absolutely right,’ Belle said. ‘She’ll never know and it won’t affect her, knowing or not knowing.’

‘But—’

‘Get in, darling.’

‘Yes, get in.’

‘Come on,’ Edward said, opening the passenger door and smiling again. ‘Come on. Please. Please. We’ll have fish and chips on the beach. Don’t make me go alone.’

‘I should be working …’ Elinor said faintly.

She glanced at Edward. He bent slightly and, with the hand not holding the door, gave her a small, decisive shove into the passenger seat. Then he closed the door firmly behind her. He was beaming broadly, and went back round to the driver’s side at a run.

‘Look at that,’ Marianne said approvingly. ‘Who’s the dog with two tails?’

‘Both wagging.’

The car lurched off at speed, in a spray of gravel.

‘He’s a dear,’ Belle said.

‘You’d like anyone who liked Ellie.’

‘I would. Of course I would. But he’s a dear in his own right.’

‘And rich. The Ferrarses are stinking—’

‘I don’t’, Belle said, putting her arm round Marianne, ‘give a stuff about that. Any more than you do. If he’s a dear boy and he likes Ellie and she likes him, that is more than good enough for me. And for you too, I bet.’

Marianne said seriously, watching the car speeding down the faraway sweep of the drive, ‘He wouldn’t be good enough for me.’

‘Darling!’

Marianne leaned into her mother’s embrace.

‘Ma, you know he wouldn’t do for me. I’m not looking for a nice guy; I’m looking for the guy. I don’t want someone who thinks I’m clever to play the guitar like I do, I want someone who knows why I play so well, who understands what I’m playing, like I do, who understands me for what I am and values that. Values me.’ She paused and straightened a little. Then she said, ‘Ma, I’d rather have nothing ever than just anything. Much rather.’

Belle was laughing. ‘Darling, don’t despair. You only left school a year ago, you’re hardly—’

Marianne stepped sideways so that Belle’s arm slipped from her waist. ‘I mean it,’ she said fiercely. ‘I mean it. I don’t want just a man, Ma. I want a soulmate. And if I can’t have one, I’d rather have nobody. See?’

Belle was silent. She was looking into the middle distance now, plainly not really seeing anything.

‘Ma?’ Marianne said.

Belle shook her head very slightly. Marianne moved closer again.

‘Ma, are you thinking about Daddy?’

Belle gave a small sigh.

‘If you are – and you are, aren’t you? – then you’ll know what I’m talking about,’ Marianne said. ‘If I didn’t get this belief in having, one day, a love of my life from you, who did I get it from?’

Belle turned very slightly and gave Marianne a misty smile. ‘Touché, darling,’ she said.

From her bedroom windows – three bays looking south and two facing west – Fanny could see across the immense lawn to the walled vegetable garden, whose glasshouses were so badly in need of repair, never mind the state of the beds themselves, or the unpruned fruit trees and general neglect visible everywhere. And there, in the decayed soft-fruit cage, with its sagging wire and crooked posts, she could see Belle, in one of her arty smock things and jeans, picking raspberries.

Of course, in a way, Belle was perfectly entitled to pick Norland raspberries. The canes themselves probably dated from Uncle Henry’s time, and in their well-meaning, amateur way, Belle and Henry had tried to look after the garden all the years they had lived at Norland. But the fact was that Norland now belonged to John. And because of John, to Fanny. Which meant that everything about it and pertaining to it was not only Fanny’s responsibility now, but her possession. Staring out of the window at her husband’s (by courtesy, only) stepmother, it came to Fanny quite forcibly that Belle was, without asking, picking Fanny’s raspberries.

It took her three minutes to cross her bedroom, traverse the landing, descend the stairs, march down the black and white floored hall to the garden door and make her way at speed across the lawn to the kitchen garden. She let the door in the wall to the kitchen garden close behind her with enough of a slam to alert Belle to the fact that she had arrived, and with a purpose.

Belle looked up, slightly dazedly. She had been thinking about something quite else, mentally arranging the furniture in a cottage she had seen, for rent, near Barcombe Cross, which she had thought might be a distinct possibility even though Elinor insisted that they couldn’t possibly afford it, and she had been picking almost mechanically while she dreamed.

‘Good morning,’ Fanny said.

Belle managed a smile. ‘Good morning, Fanny.’

Fanny stepped into the fruit cage through a torn gap in the netting. She was wearing patent-leather ballet slippers with gold discs on the toes. She looked round her. ‘This is in an awful state.’

Belle said mildly, ‘The raspberries don’t seem to mind. Look at this crop!’

She held her bowl out. Fanny gave a small dismissive sniff. ‘You’ve got a huge amount.’

‘We grew them, Fanny.’

‘All the same …’

‘I’d be happy to pick some for you, Fanny. I offered some to Harry – I thought he might like to pick them with me, but he said he didn’t like raspberries.’

Fanny said carefully, ‘We are very – selective in the fruit we give Harry.’

Belle resumed her picking. ‘Bananas,’ she said, over her shoulder. ‘Only bananas, we hear. Can that be good for him, not even to eat apples?’

There was short, highly charged pause. Then Fanny said, ‘Isn’t Elinor helping you?’

‘You can see that she isn’t.’

‘Because she isn’t here,’ Fanny said.

Belle said nothing. Fanny threaded her way through the raspberry canes until she was once again in Belle’s sightline.

‘Elinor isn’t here,’ Fanny said clearly, ‘because she is in my car, isn’t she, being driven by my brother, on her way to Brighton.’

‘And if she is?’

‘I wouldn’t want you to think I hadn’t noticed. I wouldn’t want you to think I don’t know. I wasn’t asked. I saw them. I saw them drive away.’

Belle said defiantly, ‘Edward invited her!’

Fanny leaned forward to pick a large, ripe raspberry very precisely out of Belle’s bowl. ‘He may have done. But she had no business accepting.’

Belle stepped back so that the bowl of raspberries was just out of Fanny’s reach. ‘I beg your pardon!’ she said indignantly.

Fanny looked at the raspberry in her fingers and then she looked at Belle. ‘Don’t get any ideas,’ she said.

‘But—’

‘Look,’ Fanny said. ‘Look. My father came from nowhere and ended up somewhere very successful, all through his own efforts. He was ambitious, quite rightly, and he was ambitious for his children, too. He’d be thrilled about Norland. But he wouldn’t be thrilled at all about his eldest son being – being ensnared by his son-in-law’s illegitimate half-sister with not a bean to her name. Any more than my mother would be, if she knew.’ Fanny paused, and then she said, ‘Any more than I am.’

Belle stared at her. ‘I cannot believe this, Fanny.’

Fanny waved the hand holding the raspberry. ‘It doesn’t matter what you can or can’t believe, Belle. It doesn’t matter a jot. All that matters is that when Elinor gets back from her jaunt in my car with my brother, you have just two words to say to her. Two words. Hands off. Do you get it, Belle? Hands off Edward.’

And then she dropped the raspberry on to the earth, and ground it down under her patent-leather toecap.

Edward held out a crumple of white paper. ‘Have another chip.’

Elinor was lying on her back on Edward’s battered cotton jacket, which he had spread for her on the shingle. She waved a hand. ‘Couldn’t.’

‘Just one.’

‘Not even that. They were delicious. The fish was perfect. Thank you for holding back on the vinegar.’

Edward put another chip in his mouth. ‘I have a thing for vinegar.’

Elinor snorted faintly.

‘I mean,’ Edward said, laughing too, ‘I mean vinegar in vinegar. Not in people.’

‘No names then.’

He lay down beside her, slightly turned towards her. He said comfortably, ‘We know who we mean, don’t we? And you haven’t even met my mother.’

Elinor stretched both arms up and laced her fingers together against the high blue arc of the sky. ‘Talking of mothers—’

‘Did you know,’ Edward said, interrupting, ‘that when you talk, the end of your nose moves up and down very slightly? It’s adorable.’

Elinor suppressed a smile. She lowered her arms. ‘Talking of mothers,’ she said again.

‘Oh, OK then. Mothers. What about them?’

‘Mine is so sweet, really—’

‘Oh, I know.’

‘—but she’s driving me insane. Insane. Almost every day she goes off to look at some house or other. She must be on every agent’s books in East Sussex.’

Edward put out a tentative finger and touched the end of Elinor’s nose. He said, ‘But that’s good. That’s positive.’

Elinor tried to ignore his finger. ‘Yes, of course it is, in theory. But she’s looking at stuff we can’t begin to afford. They may technically be cottages but they’ve got five bedrooms and three bathrooms and one even has a swimming pool in a conservatory thing. I ask you.’

‘But—’

Elinor turned her head to look at him, dislodging his finger. ‘Ed, we can’t actually even afford a garden shed. But she won’t listen.’

‘They don’t.’

‘You mean mothers?’

‘Mothers,’ Edward said with emphasis. ‘They do not listen.’

‘You mean yours won’t listen to you either?’

Edward rolled on his back. ‘Nobody listens.’

‘Oh, come on.’

He said, ‘I applied to Amnesty International and they said I wasn’t qualified for anything they had on offer. Same with Oxfam. And the only reason for having anything to do with the law is that Human Rights Watch might – might – give me a hearing with the right bits of paper in my hand.’

Elinor waited a moment, and then she said, ‘What are you good at, do you think?’

Edward picked a pebble out of the shingle beside him and looked at it. Then he said, in quite a different, more confident tone of voice, ‘Organising things. I don’t mean how many cases of champagne will two hundred people drink, like Robert. I mean quite – serious things. I can get things done. Actually.’