Полная версия

Полная версияSpecimens of the Table Talk of Samuel Taylor Coleridge

The clerisy of a nation, that is, its learned men, whether poets, or philosophers, or scholars, are these points of relative rest. There could be no order, no harmony of the whole, without them.

April 21. 1832

INTELLECTUAL REVOLUTIONS.—MODERN STYLEThere have been three silent revolutions in England:—first, when the professions fell off from the church; secondly, when literature fell off from the professions; and, thirdly, when the press fell off from literature.

* * * * *Common phrases are, as it were, so stereotyped now by conventional use, that it is really much easier to write on the ordinary politics of the day in the common newspaper style, than it is to make a good pair of shoes.

An apprentice has as much to learn now to be a shoemaker as ever he had; but an ignorant coxcomb, with a competent want of honesty, may very effectively wield a pen in a newspaper office, with infinitely less pains and preparation than were necessary formerly.

April 23. 1832

GENIUS OF THE SPANISH AND ITALIANS.—VICO.—SPINOSAThe genius of the Spanish people is exquisitely subtle, without being at all acute; hence there is so much humour and so little wit in their literature. The genius of the Italians, on the contrary, is acute, profound, and sensual, but not subtle; hence what they think to be humorous is merely witty.

* * * * *To estimate a man like Vico, or any great man who has made discoveries and committed errors, you ought to say to yourself—"He did so and so in the year 1720, a Papist, at Naples. Now, what would he not have done if he had lived now, and could have availed himself of all our vast acquisitions in physical science?"

* * * * *After the Scienza Nuova106 read Spinosa, De Monarchia ex rationis praescripto107.They differed—Vico in thinking that society tended to monarchy; Spinosa in thinking it tended to democracy. Now, Spinosa's ideal democracy was realized by a contemporary—not in a nation, for that is impossible, but in a sect—I mean by George Fox and his Quakers.108

April 24. 1832

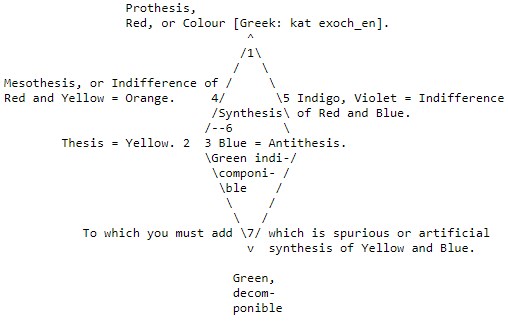

COLOURSColours may best be expressed by a heptad, the largest possible formula for things finite, as the pentad is the smallest possible form. Indeed, the heptad of things finite is in all cases reducible to the pentad. The adorable tetractys, or tetrad, is the formula of God; which, again, is reducible into, and is, in reality, the same with, the Trinity. Take colours thus:—

April 28. 1832

DESTRUCTION OF JERUSALEM.—EPIC POEMThe destruction of Jerusalem is the only subject now remaining for an epic poem; a subject which, like Milton's Fall of Man, should interest all Christendom, as the Homeric War of Troy interested all Greece. There would be difficulties, as there are in all subjects; and they must he mitigated and thrown into the shade, as Milton has done with the numerous difficulties in the Paradise Lost. But there would be a greater assemblage of grandeur and splendour than can now be found in any other theme. As for the old mythology, incredulus odi; and yet there must be a mythology, or a quasi-mythology, for an epic poem. Here there would be the completion of the prophecies—the termination of the first revealed national religion under the violent assault of Paganism, itself the immediate forerunner and condition of the spread of a revealed mundane religion; and then you would have the character of the Roman and the Jew, and the awfulness, the completeness, the justice. I schemed it at twenty-five; but, alas! venturum expectat.

April 29. 1832

VOX POPULI, VOX DEI.—BLACKI never said that the vox populi was of course the vox Dei. It may be; but it may be, and with equal probability, a priori, vox Diaboli. That the voice of ten millions of men calling for the same thing is a spirit, I believe; but whether that be a spirit of Heaven or Hell, I can only know by trying the thing called for by the prescript of reason and God's will.

* * * * *Black is the negation of colour in its greatest energy. Without lustre, it indicates or represents vacuity, as, for instance, in the dark mouth of a cavern; add lustre, and it will represent the highest degree of solidity, as in a polished ebony box.

* * * * *In finite forms there is no real and absolute identity. God alone is identity. In the former, the prothesis is a bastard prothesis, a quasi identity only.

April 30. 1832

ASGILL AND DEFOEI know no genuine Saxon English superior to Asgill's. I think his and Defoe's irony often finer than Swift's.

May 1. 1832

HORNE TOOKE.—FOX AND PITTHorne Tooke's advice to the Friends of the People was profound:—"If you wish to be powerful, pretend to be powerful."

* * * * *Fox and Pitt constantly played into each other's hands. Mr. Stuart, of the Courier, who was very knowing in the politics of the day, soon found out the gross lies and impostures of that club as to its numbers, and told Fox so. Yet, instead of disclaiming them and exposing the pretence, as he ought to have done, Fox absolutely exaggerated their numbers and sinister intentions; and Pitt, who also knew the lie, took him at his word, and argued against him triumphantly on his own premisses.

Fox's Gallicism, too, was a treasury of weapons to Pitt. He could never conceive the French right without making the English wrong. Ah! I remember—

—it vex'd my soul to seeSo grand a cause, so proud a realmWith Goose and Goody at the helm;Who long ago had fall'n asunderBut for their rivals' baser blunder,The coward whine and FrenchifiedSlaver and slang of the other side!May 2. 1832

HORNERI cannot say that I thought Mr. Horner a man of genius. He seemed to me to be one of those men who have not very extended minds, but who know what they know very well—shallow streams, and clear because they are shallow. There was great goodness about him.

May 3. 1832

ADIAPHORI.—CITIZENS AND CHRISTIANS—– is one of those men who go far to shake my faith in a future state of existence; I mean, on account of the difficulty of knowing where to place him. I could not bear to roast him; he is not so bad as all that comes to: but then, on the other hand, to have to sit down with such a fellow in the very lowest pothouse of heaven is utterly inconsistent with the belief of that place being a place of happiness for me.

* * * * *In two points of view I reverence man; first, as a citizen, a part of, or in order to, a nation; and, secondly, as a Christian. If men are neither the one nor the other, but a mere aggregation of individual bipeds, who acknowledge no national unity, nor believe with me in Christ, I have no more personal sympathy with them than with the dust beneath my feet.

May 21. 1832

PROFESSOR PARK.—ENGLISH CONSTITUTION—DEMOCRACY.—MILTON AND SIDNEYProfessor Park talks109 about its being very doubtful whether the constitution described by Blackstone ever in fact existed. In the same manner, I suppose, it is doubtful whether the moon is made of green cheese, or whether the souls of Welchmen do, in point of fact, go to heaven on the backs of mites. Blackstone's was the age of shallow law. Monarchy, aristocracy, and democracy, as such, exclude each the other: but if the elements are to interpenetrate, how absurd to call a lump of sugar hydrogen, oxygen, and carbon! nay, to take three lumps, and call the first hydrogen; the second, oxygen; and the third, carbon! Don't you see that each is in all, and all in each?

The democracy of England, before the Reform Bill, was, where it ought to be, in the corporations, the vestries, the joint-stock companies, &c. The power, in a democracy, is in focal points, without a centre; and in proportion as such democratical power is strong, the strength of the central government ought to be intense—otherwise the nation will fall to pieces.

We have just now incalculably increased the democratical action of the people, and, at the same time, weakened the executive power of the government.

* * * * *It was the error of Milton, Sidney, and others of that age, to think it possible to construct a purely aristocratical government, defecated of all passion, and ignorance, and sordid motive. The truth is, such a government would be weak from its utter want of sympathy with the people to be governed by it.

May 25. 1832

DE VI MINIMORUM.—HAHNEMANN.—LUTHERMercury strongly illustrates the theory de vi minimorum. Divide five grains into fifty doses, and they may poison you irretrievably. I don't believe in all that Hahnemann says; but he is a fine fellow, and, like most Germans, is not altogether wrong, and like them also, is never altogether right.

* * * * *Six volumes of translated selections from Luther's works, two being from his Letters, would be a delightful work. The translator should be a man deeply imbued with his Bible, with the English writers from Henry the Seventh to Edward the Sixth, the Scotch divines of the 16th century, and with the old racy German.110

Hugo de Saint Victor, Luther's favourite divine, was a wonderful man, who, in the 12th century, the jubilant age of papal dominion, nursed the lamp of Platonic mysticism in the spirit of the most refined Christianity.111

June 9. 1832

SYMPATHY OF OLD GREEK AND LATIN WITH ENGLISH.—ROMAN MIND.—WARIf you take Sophocles, Catullus, Lucretius, the better parts of Cicero, and so on, you may, just with two or three exceptions arising out of the different idioms as to cases, translate page after page into good mother English, word by word, without altering the order; but you cannot do so with Virgil or Tibullus: if you attempt it, you will make nonsense.

* * * * *There is a remarkable power of the picturesque in the fragments we have of Ennius, Actius, and other very old Roman writers. This vivid manner was lost in the Augustan age.

* * * * *Much as the Romans owed to Greece in the beginning, whilst their mind was, as it were, tuning itself to an after-effort of its own music, it suffered more in proportion by the influence of Greek literature subsequently, when it was already mature and ought to have worked for itself. It then became a superfetation upon, and not an ingredient in, the national character. With the exception of the stern pragmatic historian and the moral satirist, it left nothing original to the Latin Muse.112

A nation, to be great, ought to be compressed in its increment by nations more civilized than itself—as Greece by Persia; and Rome by Etruria, the Italian states, and Carthage. I remember Commodore Decatur saying to me at Malta, that he deplored the occupation of Louisiana by the United States, and wished that province had been possessed by England. He thought that if the United States got hold of Canada by conquest or cession, the last chance of his country becoming a great compact nation would be lost.

* * * * *War in republican Rome was the offspring of its intense aristocracy of spirit, and stood to the state in lieu of trade. As long as there was any thing ab extra to conquer, the state advanced: when nothing remained but what was Roman, then, as a matter of course, civil war began.

June 10. 1832

CHARM FOR CRAMPWhen I was a little hoy at the Blue-coat School, there was a charm for one's foot when asleep; and I believe it had been in the school since its foundation, in the time of Edward the Sixth. The march of intellect has probably now exploded it. It ran thus:—

Foot! foot! foot! is fast asleep!Thumb! thumb! thumb! in spittle we steep:Crosses three we make to ease us,Two for the thieves, and one for Christ Jesus!And the same charm served for a cramp in the leg, with the following substitution:—

The devil is tying a knot in my leg!Mark, Luke, and John, unloose it I beg!—Crosses three, &c.And really upon getting out of bed, where the cramp most frequently occurred, pressing the sole of the foot on the cold floor, and then repeating this charm with the acts configurative thereupon prescribed, I can safely affirm that I do not remember an instance in which the cramp did not go away in a few seconds.

I should not wonder if it were equally good for a stitch in the side; but I cannot say I ever tried it for that.

July 7. 1832

GREEK.—DUAL, NEUTER PLURAL, AND VERB SINGULAR.—THETAIt is hardly possible to conceive a language more perfect than the Greek. If you compare it with the modern European tongues, in the points of the position and relative bearing of the vowels and consonants on each other, and of the variety of terminations, it is incalculably before all in the former particulars, and only equalled in the last by German. But it is in variety of termination alone that the German surpasses the other modern languages as to sound; for, as to position, Nature seems to have dropped an acid into the language, when a-forming, which curdled the vowels, and made all the consonants flow together. The Spanish is excellent for variety of termination; the Italian, in this particular, the most deficient. Italian prose is excessively monotonous.

* * * * *It is very natural to have a dual, duality being a conception quite distinct from plurality. Most very primitive languages have a dual, as the Greek, Welch, and the native Chilese, as you will see in the Abbé Raynal.

The neuter plural governing, as they call it, a verb singular is one of the many instances in Greek of the inward and metaphysic grammar resisting successfully the tyranny of formal grammar. In truth, there may be Multeity in things; but there can only be Plurality in persons.

Observe also that, in fact, a neuter noun in Greek has no real nominative case, though it has a formal one, that is to say, the same word with the accusative. The reason is—a thing has no subjectivity, or nominative case: it exists only as an object in the accusative or oblique case.

It is extraordinary that the Germans should not have retained or assumed the two beautifully discriminated sounds of the soft and hard theta; as in thy thoughts—the thin ether that, &c. How particularly fine the hard theta is in an English termination, as in that grand word—Death— for which the Germans gutturize a sound that puts you in mind of nothing but a loathsome toad.

July 8. 1832

TALENTEDI regret to see that vile and barbarous vocable talented, stealing out of the newspapers into the leading reviews and most respectable publications of the day. Why not shillinged, farthinged, tenpenced, &c.? The formation of a participle passive from a noun is a licence that nothing but a very peculiar felicity can excuse. If mere convenience is to justify such attempts upon the idiom, you cannot stop till the language becomes, in the proper sense of the word, corrupt. Most of these pieces of slang come from America.113

* * * * *Never take an iambus as a Christian name. A trochee, or tribrach, will do very well. Edith and Rotha are my favourite names for women.

July 9. 1832

HOMER.—VALCKNAERI have the firmest conviction that Homer is a mere traditional synonyme with, or figure for, the Iliad. You cannot conceivefor a moment any thing about the poet, as you call him, apart from that poem. Difference in men there was in a degree, but not in kind; one man was, perhaps, a better poet than another; but he was a poet upon the same ground and with the same feelings as the rest.

The want of adverbs in the Iliad is very characteristic. With more adverbs there would have been some subjectivity, or subjectivity would have made them.

The Greeks were then just on the verge of the bursting forth of individuality.

Valckenaer's treatise114 on the interpolation of the Classics by the later Jews and early Christians is well worth your perusal as a scholar and critic.

July 13. 1832

PRINCIPLES AND FACTS.—SCHMIDTI have read all the famous histories, and, I believe, some history of every country and nation that is, or ever existed; but I never did so for the story itself as a story. The only thing interesting to me was the principles to be evolved from, and illustrated by, the facts.115 After I had gotten my principles, I pretty generally left the facts to take care of themselves. I never could remember any passages in books, or the particulars of events, except in the gross. I can refer to them. To be sure, I must be a different sort of man from Herder, who once was seriously annoyed with himself, because, in recounting the pedigree of some German royal or electoral family, he missed some one of those worthies and could not recall the name.

* * * * *Schmidt116 was a Romanist; but I have generally found him candid, as indeed almost all the Austrians are. They are what is called good Catholics; but, like our Charles the Second, they never let their religious bigotry interfere with their political well-doing. Kaiser is a most pious son of the church, yet he always keeps his papa in good order.

July 20. 1832

PURITANS AND JACOBINSIt was God's mercy to our age that our Jacobins were infidels and a scandal to all sober Christians. Had they been like the old Puritans, they would have trodden church and king to the dust—at least for a time.

* * * * *For one mercy I owe thanks beyond all utterance,—that, with all my gastric and bowel distempers, my head hath ever been like the head of a mountain in blue air and sunshine.

July 21. 1832

WORDSWORTHI have often wished that the first two books of the Excursion had been published separately, under the name of "The Deserted Cottage." They would have formed, what indeed they are, one of the most beautiful poems in the language.

* * * * *Can dialogues in verse be defended? I cannot but think that a great philosophical poet ought always to teach the reader himself as from himself. A poem does not admit argumentation, though it does admit development of thought. In prose there may be a difference; though I must confess that, even in Plato and Cicero, I am always vexed that the authors do not say what they have to say at once in their own persons. The introductions and little urbanities are, to be sure, very delightful in their way; I would not lose them; but I have no admiration for the practice of ventriloquizing through another man's mouth.

* * * * *I cannot help regretting that Wordsworth did not first publish his thirteen books on the growth of an individual mind—superior, as I used to think, upon the whole, to the Excursion. You may judge how I felt about them by my own poem upon the occasion.117 Then the plan laid out, and, I believe, partly suggested by me, was, that Wordsworth should assume the station of a man in mental repose, one whose principles were made up, and so prepared to deliver upon authority a system of philosophy. He was to treat man as man, —a subject of eye, ear, touch, and taste, in contact with external nature, and informing the senses from the mind, and not compounding a mind out of the senses; then he was to describe the pastoral and other states of society, assuming something of the Juvenalian spirit as he approached the high civilization of cities and towns, and opening a melancholy picture of the present state of degeneracy and vice; thence he was to infer and reveal the proof of, and necessity for, the whole state of man and society being subject to, and illustrative of, a redemptive process in operation, showing how this idea reconciled all the anomalies, and promised future glory and restoration. Something of this sort was, I think, agreed on. It is, in substance, what I have been all my life doing in my system of philosophy.

* * * * *I think Wordsworth possessed more of the genius of a great philosophic poet than any man I ever knew, or, as I believe, has existed in England since Milton; but it seems to me that he ought never to have abandoned the contemplative position, which is peculiarly—perhaps I might say exclusively—fitted for him. His proper title is Spectator ab extra.

* * * * *July 23. 1832

FRENCH REVOLUTIONNo man was more enthusiastic than I was for France and the Revolution: it had all my wishes, none of my expectations. Before 1793, I clearly saw and often enough stated in public, the horrid delusion, the vile mockery, of the whole affair.118

When some one said in my brother James's presence119 that I was a Jacobin, he very well observed,—"No! Samuel is no Jacobin; he is a hot-headed Moravian!" Indeed, I was in the extreme opposite pole.

July 24. 1832

INFANT SCHOOLSI have no faith in act of parliament reform. All the great—the permanently great—things that have been achieved in the world have been so achieved by individuals, working from the instinct of genius or of goodness. The rage now-a-days is all the other way: the individual is supposed capable of nothing; there must be organization, classification, machinery, &c., as if the capital of national morality could be increased by making a joint stock of it. Hence you see these infant schools so patronized by the bishops and others, who think them a grand invention. Is it found that an infant-school child, who has been bawling all day a column of the multiplication-table, or a verse from the Bible, grows up a more dutiful son or daughter to its parents? Are domestic charities on the increase amongst families under this system? In a great town, in our present state of society, perhaps such schools may be a justifiable expedient—a choice of the lesser evil; but as for driving these establishments into the country villages, and breaking up the cottage home education, I think it one of the most miserable mistakes which the well-intentioned people of the day have yet made; and they have made, and are making, a good many, God knows.

July 25. 1832

MR. COLERIDGE'S PHILOSOPHY.—SUBLIMITY.—SOLOMON.—MADNESS.—C. LAMB—SFORZA's DECISIONThe pith of my system is to make the senses out of the mind—not the mind out of the senses, as Locke did.

* * * * *Could you ever discover any thing sublime, in our sense of the term, in the classic Greek literature? never could. Sublimity is Hebrew by birth.

* * * * *I should conjecture that the Proverbs and Ecclesiastes were written, or, perhaps, rather collected, about the time of Nehemiah. The language is Hebrew with Chaldaic endings. It is totally unlike the language of Moses on the one hand, and of Isaiah on the other.

* * * * *Solomon introduced the commercial spirit into his kingdom. I cannot think his idolatry could have been much more, in regard to himself, than a state protection or toleration of the foreign worship.

* * * * *When a man mistakes his thoughts for persons and things, he is mad. A madman is properly so defined.

* * * * *Charles Lamb translated my motto Sermoni propriora by—properer for a sermon!

* * * * *I was much amused some time ago by reading the pithy decision of one of the Sforzas of Milan, upon occasion of a dispute for precedence between the lawyers and physicians of his capital;—Paecedant fures—sequantur carnifices. I hardly remember a neater thing.

July 28. 1832

FAITH AND BELIEFThe sublime and abstruse doctrines of Christian belief belong to the church; but the faith of the individual, centered in his heart, is or may be collateral to them.120

Faith is subjective. I throw myself in adoration before God; acknowledge myself his creature,—simple, weak, lost; and pray for help and pardon through Jesus Christ: but when I rise from my knees, I discuss the doctrine of the Trinity as I would a problem in geometry; in the same temper of mind, I mean, not by the same process of reasoning, of course.