Полная версия:

Wagnerism

REVUE WAGNÉRIENNE

By 1885, a new phalanx of writers occupied the front lines of French literature. Verlaine and Mallarmé were its leaders, and at least a dozen young poets filled out its ranks. Paris had seen successive waves of romanticism, Parnassianism, and naturalism; this latest vanguard, which had allies in the visual arts and the theater, touched upon uncanny images, spectral apparitions, the world of dreams, clusters of words so dense that they resisted understanding. The poets of the eighties reacted against the naturalist claim to be showing the world as it is, and, more widely, to materialist and evolutionary understandings of the human condition. Here, behind the veil of reality, was the hidden truth of existence, at the edge of the sayable. The unavoidable question arose of what the new movement should be called. One possible term was “decadence,” which Bourget codified in 1881, with his theory of the disintegration of language. Two years later, Verlaine published his poem “Langueur,” which begins with the line “I am the Empire at the end of the decadence.” This usage reached unashamedly for decadence in the old, disreputable sense—excess amid collapse.

For that very reason, though, many young poets rejected the label. In 1885, Jean Moréas replied to an unflattering essay on “decadent poets” by repudiating bohemianism in the Baudelaire-Verlaine vein, preaching instead a devotion to “the pure Concept and the eternal Symbol.” In passing, Moréas proposed the word “symbolist.” In a subsequent manifesto, he expanded on the term, explaining that the new poetry obeyed an evolutionary logic while revealing “esoteric affinities with primordial Ideas.”

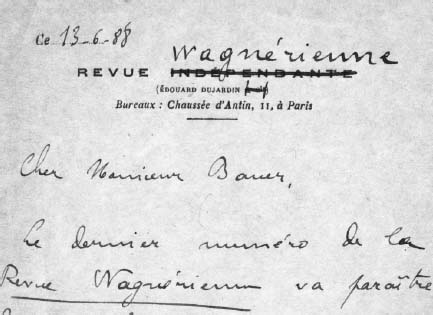

That same year, patrons of the Concerts Lamoureux were offered copies of a new magazine called the Revue wagnérienne. It was the brainchild of Édouard Dujardin, the twenty-three-year-old son of a sea captain who supported his literary endeavors with a stipend from his parents. Dujardin also worked out a system for winning at the racetrack, which boosted his coffers until he tried to break the bank at Monte Carlo. Dandyish and bemonocled, Dujardin wore a red vest embroidered with tiny swans, in honor of Lohengrin. He caught the Wagner virus in May 1882, when he heard the Ring in London. That summer, he went to Bayreuth for the premiere of Parsifal, and at the following year’s festival he greeted French arrivals at the railway station by blowing discordantly on a horn in what he believed to be a Siegfried manner.

In Wagnerian circles in Paris, Dujardin fell in with two other young men who shared his musical and literary passions. One was Téodor de Wyzewa, a Polish émigré critic with a yen for Villiers, Mallarmé, and Jules Laforgue. The other was Houston Stewart Chamberlain, an expatriate Englishman who would eventually marry into the Wagner family and become Bayreuth’s resident racist philosopher. In the early eighties, Chamberlain was more liberal in his opinions, and avidly read the latest French literature. A Wagnerite from the late seventies onward, he, too, had attended the first performances of Parsifal. Several times he hovered in the Meister’s vicinity, too overawed to speak to him. Together, Dujardin, Wyzewa, and Chamberlain decided to found a Wagnerian journal, dedicated not only to the music itself but to the increasingly large number of artists who took it as a model.

At first, the Revue looked to be an offshoot of the Bayreuther Blätter, the house periodical at Bayreuth. It offered translations of Wagner’s writings, analyses of the operas, schedules of performances, and other tidbits. Then, in the third issue, the Revue took an unusual turn, with the publication of a prose poem about the Tannhäuser overture. This was the work of Joris-Karl Huysmans, who had already written provocatively about Wagner in his popular and scandalous novel À rebours (Against the Grain). Des Esseintes, that book’s protagonist, bemoans the vulgarity of concerts like the Pasdeloup series, where a “man with the aspect of a carpenter beats a sauce in the air and massacres disconnected episodes of Wagner, to the immense delight of an ignorant crowd!” The music is better enjoyed at home, where the mind can roam free. In his Tannhäuser piece for the Revue, Huysmans focuses on the Venusberg music and its “screams of uncontained desires, cries of strident lecheries, impulses from the carnal beyond.” Venus is “the incarnation of the Spirit of Evil, the effigy of omnipotent Lust, the image of the irresistible and magnificent Sataness.”

Dujardin’s essay “The Theoretical Works of Richard Wagner,” which also appeared in the Revue’s third issue, ponders the composer’s capacity to disclose deep, hidden truths through the medium of art. Renouncing false realism, the poet-artist will “transport men into the ideal and real realm of the Unity.” Here was the transubstantiation that so many Symbolists sought. The difference was that, unlike Wagner, they felt little need to reach a wide audience or to speak in a readily accessible way. In the words of Edmund Wilson: “The symbols of the Symbolist school are usually chosen arbitrarily by the poet to stand for special ideas of his own.”

Wyzewa contributed a series of visionary essays that tracked Wagnerism in different artistic fields. In an article on literature, the critic writes that “art re-creates life by way of Signs,” although one must detach these signs from conventional referents in order to grasp the perpetual flux of emotion. This agenda sounds Nietzschean, and, indeed, Wyzewa helped to introduce French readers to the philosopher. Wagner and his fellow composers have captured that flux in sound; other arts are striving for the same effect. Wyzewa imagines a new kind of novel that would dive into a single consciousness, duplicating the ebb and flow of thought and feeling. In the visual arts, Wagnerism figures not only among the realists but also among adherents of the “Poetry of painting,” who combine “contours and nuances in pure fantasy.” Recent works by Gustave Moreau, Odilon Redon, and Edgar Degas qualify as “Wagnerian deeds.” In the post-Wagnerian music of the future, scores would be read rather than played.

The final issue of the Revue’s first year featured a sequence of eight sonnets, under the heading “Hommage à Wagner.” The poets were Verlaine, Mallarmé, Wyzewa, Dujardin, René Ghil, Stuart Merrill, Charles Morice, and Charles Vignier. Except for the first two, they were in their early or mid-twenties—foot soldiers of Symbolism. The work is mostly of the second rank, but it colorfully exhibits the symptoms of Wagnérisme as it spread through the Third Republic. Merrill pictures a cavalcade of heroes—Lohengrin, Tannhäuser, and Parsifal the Chaste—in gold armor under purple banners. (Merrill, an American based in Paris, planned a cycle of twenty-two Wagner sonnets, of which he completed only four.) Ghil renders music as a tender virgin set upon by a virile composer. Morice associates Wagner with fiery hordes and bloody tumult. Wyzewa dips into the domain of sleep and waking dreams. Dujardin bows before a Magus, a “Blasphemer of the Ordinary,” who unveils the “other universe” beyond the quotidian.

The Symbolists gave much thought to the innate musicality of the raw materials of language. In 1886, Ghil, who was once so thunderstruck by a Lamoureux Wagner concert that he aimlessly wandered the streets of Paris after midnight, produced Treatise of the Word, which, to quote Joseph Acquisto, attempts to establish “scientific correspondences among vowels, consonants, colors, orchestral instruments, and emotions.” Undoubtedly inspired by Arthur Rimbaud’s 1883 poem “Vowels,” Ghil devises the following arrangement:

A, black; E, white; I, blue; O, red; U, yellow

A, organs; E, harps; I, violins; O, brass; U, flutes

In a section on Wagner, Ghil pledges that the new musical poet can meet the Meister’s challenge: “In the Brass, the Woodwinds, the Strings that ravish him, through the close and subtle relationships of Colors, Timbres, and Vowels, he will seek the least poorly concordant Speech, in words sounding as notes.” (Wagnéristes had a tendency toward Germanic capitalization.) According to Francis Vielé-Griffin, another American-born poet who joined this circle, one group of Symbolists was known as the “Symbolistes-Instrumentistes.” Seeking to become more musical, they got hold of a harmonium and hoisted it up to the apartment where they gathered. Unfortunately, it turned out that no one knew how to play the instrument, and so “the organ remained perpetually mute, reinforcing by the solitary solemnity of its presence an atmosphere already rather thick with verbal lyricism.”

Dujardin, in a poetic cycle titled Litanies, went as far as to supply a notated musical realization. Stilted in compositional terms, Litanies is of greater significance in French literary history. The stately metrical structures of classical poetry are giving way to vers libre, or free verse. Dujardin later testified that Wagner impelled his first thoughts in this direction: “Because the musical phrase had won freedom of rhythm, it was necessary to win an analogous rhythmic freedom for verse.” The composer’s librettos are already a kind of free verse, liberated from the tight rhyme schemes that had governed most opera before him. In collaboration with Chamberlain, Dujardin concocted a “literal” translation of the opening scene of Rheingold. It begins: “Weia! Waga! vogue, ô la vague, vibre en la vive!” The language of Litanies is nearly the same: “Les voiles voguent sur les vagues” (“Sails waft over the waves”). As Vielé-Griffin concluded, “music made symbolist expression possible.”

Even bolder is Dujardin’s 1887 novel Les Lauriers sont coupés (The Laurels Are Cut Down), which answered Wyzewa’s call for a new kind of Wagnerian fiction, one that would record a single character’s ideas, perceptions, and emotions over a short period. Les Lauriers—the title comes from an old French children’s song, “Nous n’irons plus au bois”—describes the inner life of a dandy wandering about Paris one evening. Passages of insistent repetition bring to mind the heaving texture of the Tristan prelude:

The candles on the mantelpiece are lit; here’s the white bed, soft, the carpets; I lean against the open window; outside, behind me, I feel the night; black, cold, sad, sinister night; the dark where appearances change; the silence where sands murmur; the tall trees packed black together; the bare walls; and the windows dim with the unknown, and the windows lighted, unknown; in the pallor of the sky, this vibration of the weeping eyes of the stars; the secret of opaque, mysterious shadows, mixed into something fearsome; there, some unknown, fearsome thing … I shudder; quickly, I turn round, grip the window, I push it to, I close it, quickly … Nothing … The window’s closed … And the curtains? I draw them to, like this … Night is abolished.

Dujardin explained his method in a later essay titled “The Interior Monologue.” Just as Wagner’s music consists of a succession of motifs that suggest psychological states, the interior monologue is a “succession of short sentences, each of which also expresses a movement of the soul, the similarity being that they are related to each other not according to a rational order but according to a purely emotional order, outside of any intellectualized arrangement.” At the time, this idea had few imitators, but its moment would arrive in the next century: James Joyce cited Les Lauriers as a precedent for Ulysses.

VERLAINE AND MALLARMÉ

Mallarmé by Manet

Experiments in endless melody and vers libre aside, the most striking tributes in the Revue wagnérienne were in sonnet form. Verlaine’s “Parsifal” and Mallarmé’s “Hommage” both appeared in the “Hommage à Wagner” issue of January 1886. Each poem heralded a distinct new strain of Wagnerism. Verlaine hosted a Wagnerism of the Decadence, spiked with illicit sexuality. Mallarmé augured a modernist Wagner, esoteric and abstract. Such work disconcerted the more conventional-minded supporters of the Revue wagnérienne. The magazine’s split identity—part fan publication, part avant-garde periodical—proved untenable, and Dujardin shut it down after the third year.

Dujardin had difficulty extracting a sonnet from Verlaine, who was living in squalid conditions in a small room behind a wine shop. The poet had recently served his second prison term, after threatening to strangle his mother; the first was for shooting Rimbaud. (Almost alone among French writers of the period, Rimbaud was indifferent to Wagner. An obscene drawing in one of his letters, showing a man labeled “Wagner” with a bottle of Riesling inserted into his rectum, has been identified as a reference not to the composer but to an unpopular landlord.) The Irish novelist George Moore, who accompanied Dujardin when the editor went to collect Verlaine’s poem, recalled that a young man “with a face so rosy that he reminded me of a butcher-boy” opened the door. The sonnet was handed over, but Moore doubted whether it could be published, because of its eyebrow-raising variation on the theme of Parsifal’s threatened chastity. Although the syntax is equivocal, the boy savior seems tempted not only by Kundry and the Flower Maidens but also by a fellow young male.

Parsifal has conquered the Maidens, their pretty

Babble and amusing lust, and his inclination

Toward the Flesh of virgin boy who is enticed

To love light breasts and pretty babble;

He has conquered the beautiful Woman of subtle heart,

Spreading fresh arms and arousing throat;

Having conquered Hell, he returns to his tent

With a heavy trophy on his boyish arm—

The lance that pierced the Flank supreme!

He has healed the king, is king himself,

Priest of the most holy essential treasure.

In robes of gold, he worships, as glory and symbol,

The pure vessel where the True Blood shines.

—And, O those children’s voices singing in the dome!

The sonnet wavers between sincere religiosity—Verlaine gestured toward Catholicism in his last years—and unrepentant sensualism. The final line, with its slightly too excited intake of breath, has a campy ring. The poem looks ahead to a turn-of-the-century homoerotic culture in which the composer’s works become an emblem of outlaw desire.

Mallarmé, whom Verlaine generously celebrated in his 1884 anthology Les Poètes maudits, remade Wagner in his own image: opulent, intricate, ambiguous. This most recondite of nineteenth-century poets took pride in the drabness of his lineage, describing himself as the scion of an “uninterrupted series of functionaries in the Administration and the Registry.” Born in Paris in 1842, Mallarmé lost his mother and sister early. He had the feeling of being an orphan, of having come from nowhere. By the time he was twenty, he had decided upon a literary career. He took jobs teaching English in the provinces, and in his spare time worked on his early masterpieces, “Hérodiade” and “The Afternoon of a Faun.” Having dabbled in Romantic and Parnassian moods, he found his own strict and strange style. “I am inventing a language,” he wrote in 1864, “which must necessarily spring from an entirely new poetics, which I could define in these few words: Paint not the thing but the effect it produces … All words must efface themselves before the sensation.”

Like van Gogh, Mallarmé felt that music had moved ahead of other art forms. Poets, like painters, must catch up. In an 1862 essay insincerely titled “Art for All,” Mallarmé begins with a famous proposition—“Everything that is sacred and wishes to remain sacred envelops itself in mystery”—and praises the art of music for holding fast to its secrets. “If we casually open up Mozart, Beethoven, or Wagner and throw an indifferent eye on the first page of their work, we are gripped with a religious astonishment at the sight of these macabre processions of severe, chaste, and unknown signs.” Poetry is lacking in such mystery; Mallarmé will restore it. All this harks back to Wagner’s theorizing on the untapped potential of musical drama.

The young Mallarmé had few opportunities to hear Wagner’s music live, but he surely encountered it in the salons. Heath Lees, in his book Mallarmé and Wagner, has found traces of the composer in early poems like “Sainte” and “Hérodiade.” Villiers, whom Mallarmé revered, stimulated a deeper interest. When Villiers and Mendès came to stay with the poet in 1870, after their visit to Tribschen, they were undoubtedly full of talk of the “palmiped of Lucerne.” Still, Wagnerism remained dormant in Mallarmé’s work for some time. Indeed, Mallarmé was somewhat dormant himself; for fifteen years, he published almost nothing. The explosion of so-called decadent or Symbolist art in the mid-eighties revived him. After Verlaine and Huysmans paid tribute, Mallarmé found himself with a bevy of young acolytes. Among them were Dujardin and Wyzewa, of the Revue wagnérienne.

In April 1885, Dujardin took Mallarmé to an all-Wagner event at the Concerts Lamoureux, which included the Tannhäuser overture, Siegfried’s Funeral Music, and the preludes to Tristan and Parsifal. Mallarmé was riveted by music and audience alike. The word “foule,” “crowd,” occurs often in his writing on Wagner, and it is never entirely free of the shudder of horror that Huysmans’s Des Esseintes feels when he visits the Concerts Populaires. From then on, though, Mallarmé seldom missed a Lamoureux event. Even in high summer he would greet his younger followers at the gate in formal attire, an impeccable top hat on his head. He would take notes as he listened, perhaps with ideas for poems hatching in his mind. Paul Valéry, one of the adepts, said that Mallarmé “left the concerts full of sublime jealousy.”

Dujardin asked Mallarmé to write for the Revue. The result was “Richard Wagner, Reverie of a French Poet,” which appeared in August 1885. “Nothing has ever seemed so difficult to me,” Mallarmé wrote to Dujardin, very much in the style of a harried working writer. “Just think, I am sick, I am more than ever a slave. I have never seen anything of Wagner’s, and I want to create something original and precise, something which is not beside the point. I need more time. I will work on nothing else, you have my word, until this is done.”

Mallarmé begins with praise for Wagner’s renovation of decrepit theatrical traditions. Music “penetrates and envelops the Drama through its dazzling will.” Characters become manifest in the medium of sound: we encounter “a god dressed in the invisible folds of a fabric of chords,” we experience the “wave of Passion” that comes pouring through a single hero, so that “Legend is enthroned in the footlights.” But Wagner stops short of the true origin of poetic mystery: “Everything refreshes itself in the primitive stream: not to the source.” The inhibiting factor is myth, which supposedly speaks to people of many traditions but in fact falls prey to parochialism. The exacting French mind cannot accept it. We need a new universal fable, “virgin of everything, place, time and known characters,” starring a hero with no name. “Everything moves toward some supreme bolt of light, from which awakens the Figure that None is, whose rhythm, taken from the symphony, comes from the mimicking of each musical attitude, and liberates it!” Mallarmé envisions a poetry that imitates music, surpasses it, and stages in the theater of the mind the higher drama that Wagner sought in vain.

The “Reverie” ends with a semi-ironic fanfare to the “Genius” and a jibe at the Wagnerites who crowd the pages of the journal in which Mallarmé is writing. “O Wagner,” Mallarmé writes, “I suffer and reproach myself, in minutes marked by lassitude, for not numbering myself among those who, bored with everything in order to find definitive salvation, go straight to the edifice of your Art, for them the end of the road.” In fact, this crowded temple is only halfway up the slope of a holy mountain, at the top of which is the “menacing summit of the absolute.” Mallarmé pictures himself pausing at the Meister’s shrine, “drinking from your convivial fountain,” and gazing up at that cold peak, which no one seems prepared to scale. “No one!” Mallarmé says again. The reader is left to imagine that a solitary climber, having stocked up at the Wagnerian base camp, is set to perform the impossible feat.

The following January, Mallarmé’s “Hommage,” also known as “Hommage à Wagner,” appeared next to Verlaine’s sonnet in the Revue. Needless to say, the poem is free of misty word-pictures of swan knights and Valkyries. Mallarmé claimed that it was an admission of defeat—“the melancholy of a poet who sees the old poetic front collapse, and the luxury of words grow pale, before the rising of the sun of contemporary Music of which Wagner is the latest god.” This faux-pessimism masks an exercise of poetic might. Ensconced in sonnet form, poetic language wraps itself in a new kind of sacred mystery.

Le silence déjà funèbre d’une moire

Dispose plus qu’un pli seul sur le mobilier

Que doit un tassement du principal pilier

Précipiter avec le manque de mémoire.

Notre si vieil ébat triomphal du grimoire,

Hiéroglyphes dont s’exalte le millier

À propager de l’aile un frisson familier!

Enfouissez-le moi plutôt dans une armoire.

Du souriant fracas originel haï

Entre elles de clartés maîtresses a jailli

Jusque vers un parvis né pour leur simulacre,

Trompettes tout haut d’or pâmé sur les vélins,

Le dieu Richard Wagner irradiant un sacre

Mal tû par l’encre même en sanglots sibyllins.

The already funereal silence of a cloth

Places more than a single fold on the furniture,

Which the settling of the central pillar

Must drag down with default of memory.

Our old triumphal revels of the spellbook,

Hieroglyphs exalted by the millions

To spread a familiar shiver of the wing!

Bury it for me in a cupboard.

Out of the original smiling fracas hated

Among the master clarities there has sprung

Up to the square born for their simulation

Gold trumpets swooning aloud on vellum,

The god Richard Wagner, irradiating a rite

Scarcely silenced by the ink itself in sibylline sobs.

The poem defies explication, never mind translation. Some readers, like Wyzewa, took it as a eulogy, seeing the funereal furniture of the first quatrain as a metaphor for a spent literary art and Wagner as a “sovereign of the Scene” who brings renewal. Since the composer had died not long before, he may also be present in the opening lines: he, too, could be a dusty book of spells. Louis Marvick sees the entire sonnet as a critique, those golden trumpets representing the “stridency of Wagner’s music.”

The meaning of almost every line or phrase is up for grabs. Consider “Du souriant fracas originel haï.” What is this fracas? Who hates it? Robert Greer Cohn identifies it as the ancient art of “pure Beauty,” abhorred by the false artists of the marketplace. Heath Lees relates it to the Wagner scandals of 1860 and 1861. For Gardner Davies, the fracas is the squiggle of musical notation; for Bertrand Marchal, it is the original force of primitive art. Several commentators believe that the final lines suggest some festive Bayreuth scene. Mallarmé never visited the Festspielhaus, but he probably knew of the ritual that summons the audience back to their seats toward the end of each Bayreuth intermission: brass players assemble on the front balcony and intone motifs from the opera of the day. Interpreters more or less agree that the last line pivots toward the musical literature or literary music of Mallarmé’s dreams. That art exists in the form of ink, but it is not truly silent (mal tû); its music speaks in “sibylline sobs.”