Полная версия:

Wagnerism

He always brought in a festival,” Mallarmé said. “Time annulled itself those nights.” The Goncourt brothers recalled the “feverish eyes of a victim of hallucinations, the face of an opium addict or a masturbator, and a crazy, mechanical laugh which came and went in his throat.” This absinthe-breathed bohemian was, in fact, the scion of an ancient family, as his page-wide name testifies. Born on the Brittany coast, Villiers could claim proximity to the romance of Tristan: the hero comes from a Breton line, and, in Wagner’s version, dies in the family castle. One of Villiers’s distant ancestors had been the Grand Master of the Knights of Malta, and family lore held that he left a great treasure buried somewhere. Villiers’s father, Joseph, engaged in ill-advised real-estate ventures in order to carry out excavations in Brittany. According to Villiers’s biographer, Alan Raitt, the only thing Joseph ever found was a dinner service. His son inherited the fixation on lost glory, transmuting it into literary fantasy. Auguste gained early notoriety for having declared his candidature—seriously or not, no one could be sure—for the throne of Greece.

Villiers’s poems, plays, novels, and tales elude the usual literary categories. How to classify The Future Eve, a kind of baroque science-fiction novel in which Thomas Alva Edison invents a female android? This author is most approachable, though not necessarily most likable, when he is engaging in vicious satire: his collections Cruel Tales and Tribulat Bonhomet rail against bourgeois fatuity and callousness. In one story, the insufferable Dr. Bonhomet breaks the necks of swans, because he has heard that the birds sing most beautifully when they die. Villiers suffered from the usual failings of male European writers of the period: antisemitism, misogyny, elitism. William Butler Yeats liked to quote a characteristic line from Villiers’s mystical drama Axël: “As for living, our servants will do that for us.”

Music-mad from youth onward, Villiers was an energetic if eccentric pianist who, like Nietzsche, specialized in improvisations. He met Baudelaire a year or two before the Tannhäuser scandal, and a shared regard for Wagner cemented their friendship. “I will play Tannhäuser for you once I am settled in your neighborhood,” Villiers wrote. He also fell in with Catulle Mendès, a handsome poet and novelist who floated through Paris society beneath waves of Lisztian hair. The son of a Sephardic Jewish father and a Catholic mother, Mendès won early fame—and a brief prison term—by publishing mildly erotic poetry in his Revue fantaisiste. That short-lived journal, founded in 1861, was an early organ of the Parnassian movement, which valued formal poise and exquisite precision in the Gautier manner. In 1866, Mendès married Judith Gautier, Théophile’s daughter, who was on the verge of her own significant literary and artistic career; the two had met at one of Pasdeloup’s concerts.

In 1869, the Mendès couple, having proved their worth as combative Wagnéristes, received an invitation to visit the composer in Tribschen. Villiers joined them on the pilgrimage. The itinerary also included Munich, where rehearsals for the premiere of Rheingold were under way. Beforehand, Villiers had written a story titled “Azraël,” which he dedicated to Wagner, “prince of profound music.” Oddly, it was on an Old Testament Jewish theme, depicting King Solomon in conversation with the Angel of Death. As the party approached Tribschen, Villiers displayed mounting elation. He gave Wagner the obscure nickname “palmiped of Lucerne,” and exclaimed, “He is cubic!”

The palmiped met them on the railway platform, wearing a large straw hat, which made him look like Wotan. Gautier remembered being fixed for a full, silent minute by the soul-scoping intensity of his gaze. In letters home, Villiers described the “fabulous being” in terms suitable for the cruel angels and crazed scientists of his stories: “Something like immortality made visible, the other world rendered transparent, creative power pushed to a fantastic point, and, with that, the sweat and the shining of genius, the impression of the infinite around his head and in the naïve profundity of his eyes. He is terrifying.” He is “the very man of whom we have dreamed; he is a genius such as appears upon the earth once every thousand years.”

Cosmic ramifications notwithstanding, Wagner acted much of the time like a hyperactive child. Mendès has him throwing his hat in the air, dancing about, gesturing with nervous excitement, and talking without pause. One day, he made a catlike jump from an upper story of the house into the garden. When Villiers was later asked whether the composer was a pleasant conversationalist, he replied, “Do you imagine, sir, that the conversation of Mount Etna is pleasant?” Like Nietzsche and Baudelaire, Villiers experienced Wagner as a human volcano.

The next year, Villiers, Mendès, and Gautier set out on a second Wagner vacation, witnessing the premiere of Walküre in Munich and paying another visit to Tribschen. This time, the Franco-Prussian War intervened. Otto von Bismarck had manipulated a diplomatic dispute into a major crisis, and Napoleon III declared war on July 19, just as the French party—now including the composers Camille Saint-Saëns and Henri Duparc—alighted in Lucerne. Despite the news, the company sat enthralled as Wagner and Hans Richter performed excerpts from the Ring. “It is the Nibelungen, all the night of time,” Villiers wrote. The Nietzsche siblings, Friedrich and Elisabeth, also dropped by, making for a singular constellation of personalities. The French had hoped to stay for Richard and Cosima’s wedding, but this was delayed for legal reasons, and tensions were simmering. “R. demands of our friends that they understand how much we hate the French character,” Cosima noted. The Wagners became exasperated by Villiers’s “bombastic style and theatrical presentation”—a severe reprimand in this household. Russ, the chief family dog, bit Villiers’s hand. On July 30, the French departed, announcing their intention to visit a “friend in Avignon,” who turned out to be Stéphane Mallarmé.

Villiers never made it to Bayreuth for the Ring. Reportedly, he broke down in tears when he realized that he couldn’t afford to go. His Wagnermania persisted, reaching its apex in Axël, which once loomed over fin-de-siècle literature as a successor to Faust. In 1931, the American critic Edmund Wilson honored Villiers’s fading fame by giving the title Axel’s Castle to his history of Symbolist and modernist literature. The play first took shape at the time of Villiers’s visits to the Wagners, for whom he may have read aloud an early draft. The euphoric demise of its self-annihilating lovers, Axel d’Auersperg and Sara de Maupers, smacks of Tristan und Isolde; its story of fatally alluring gold, meanwhile, recalls the monetary curse of the Ring, not to mention the treasure-hunting escapades of Villiers’s father. Villiers was still revising and expanding the play when he died, in 1889. It reached the stage only in 1894, in a performance that lasted nearly five hours, about as long as Tristan itself. “Seldom has utmost pessimism found a more magnificent expression,” said Yeats, who was present for the occasion.

The climax of the play is like Tristan and Götterdämmerung superimposed. Sara, having fled a convent, arrives in Axel’s castle in the Black Forest, led there by a mysterious book. Axel briefly engages her in combat, gazes upon her, and falls in love. He comes to resemble not only Tristan and Siegfried but also Wotan with Brünnhilde (“I will close your eyes of paradise”) and Siegmund with Sieglinde (“Sara, my virginal mistress, my eternal sister”). What to do with the sudden onset of passion? Sara wants to flee to a remote locale and “listen to the hummingbirds in some hut in the Floridas.” Axel is unconvinced: “Oh! the external world! Let us not be dupes of that old slave.” To break the veil of illusion, he says, they should kill themselves at once. After a certain amount of hesitation, Sara agrees. As the humble songs of a village marriage are heard from outside, she draws poison from the ring on her finger. Axel expresses the hope that the rest of the human race will follow suit. After the lovers die, though, the stage directions dictate a different outcome: “Disturbing the silence of the terrible place where two human beings have just dedicated their souls to the exile of Heaven—we hear from outside the distant murmurs of the wind in the vastness of the forests, the vibrations of awakening space, the swell of the plains, the hum of life.” The forest murmurs on; the world has not committed suicide at Axel’s behest. The ironist in Villiers shows the limits of his characters’ transcendent longing.

Lost to history are Villiers’s fabled one-man Wagner entertainments. Joris-Karl Huysmans left a memorable description: “After the meal, he sat down at the piano and, lost, out of this world, sang, in his feeble, cracked voice, several pieces by Wagner, among which he interpolated barracks choruses, joining it all together with strident laughter, crazed nonsense, and strange verses. No one possessed in the same degree the power to heighten farce and make it shoot bewildered into the beyond; he always had a punch-bowl flaming in his brain.”

MODERN PAINTERS

Cézanne, Pastorale

More than a hundred thousand soldiers were killed during the Franco-Prussian War. One of them was the brilliant young Impressionist painter Frédéric Bazille, who had been a regular at Pasdeloup’s concerts and had fantasized about meeting Wagner. After the conflict, the composer’s reputation in France slumped again, thanks in part to his genius for insult. In 1873, he dismayed even his most die-hard French fans by publishing a would-be Aristophanic farce titled A Capitulation, which made light of the siege of Paris in the fall and winter of 1870. In the hardest days, Parisians resorted to eating rats and other animals. Wagner’s play, for which he thankfully wrote no music, calls for a ballet corps of human-sized rats. Catulle Mendès was particularly incensed, though he could not bring himself to cut all ties. A Hungarian Jewish friend of the author’s kept a bust of Wagner with a laurel wreath on its head and a cord around its neck. Mendès adopted the same attitude, admiring and despising his old idol in equal measure.

Between 1870 and 1887 there was only one full staging of Wagner in France—a Lohengrin in Nice, in 1881. Orchestral concerts and private events became the main conduit for his music. Pasdeloup soon resumed programming the composer in his Concerts Populaires, causing a predictable ruckus. Boos, whistles, and shouts of “À la porte Wagner!” mingled with loud cheers. Saint-Saëns, his attitude altered since he visited Tribschen with Villiers and company, accused Pasdeloup of being a German agent. In the eighties, the younger conductors Édouard Colonne and Charles Lamoureux joined the crusade, including heavy doses of Wagner on their series. Lamoureux, the most musically ambitious of the three, began presenting entire acts of the operas. In 1884, he led Act I of Tristan, with the audience listening in rapt silence. In the same period, a society called Le Petit Bayreuth, which had been operating partly in secret to avoid hostile demonstrations, offered excerpts from the Ring and Parsifal.

Supreme among the Wagnéristes was Judith Gautier, who, after separating from Mendès, had developed an intimacy with the composer that probably remained platonic. The author of several finely drawn novels on East Asian themes, Gautier advised Wagner on Eastern thought and culture, contributing to the ambience of Parsifal, which she translated into French. In 1880, Gautier organized a series of Wagner lecture-concerts at the Nadar photography studio, and in 1898 she presented a puppet-theater adaptation of Parsifal, for which she crafted dozens of figurines. The latter project led to a break with Cosima, who had tolerated Gautier’s ambiguous relations with her husband but could not condone a possible breach of copyright. That contretemps did not diminish Gautier’s enthusiasm. In later years, she would show visitors her collection of Wagner relics, including a piece of bread into which the Meister had bitten on the day of the first Parsifal. Her menagerie of pets featured a raven named Wotan.

If the war had dampened French Wagnerism, the composer’s death seemed to ignite it again. “Curious people!” Tchaikovsky wrote from Paris. “It is necessary to die in order to attract their attention.” At the Bayreuth Festival of 1886, the number of French visitors exploded, from a few dozen to well over a hundred. Back home, the Wagner contingent could turn rowdy. One evening, the critic Albert Aurier, an early promoter of van Gogh and Gauguin, got into a fracas with the police after marching through the streets with a crowd of friends, singing the melody of “The Ride of the Valkyries” at full volume. “Sir, I was singing Wagner,” Aurier told an officer. “And I know of no law that prevents it.”

In 1887, Lohengrin finally received a full staging in Paris, amid an uproar that almost outdid the Tannhäuser affair of 1861. The Opéra-Comique had planned to produce the opera the previous year, but retreated in the face of a patriotic press campaign that cast Wagner as a warmonger rather than an artist. An academic painter threatened to incite a riot by packing the theater with two hundred toga-wearing art students. Lamoureux then entered the fray, giving notice that he would present Lohengrin at the Éden-Théâtre. A Franco-German dispute known as the Schnaebelé Affair intensified the inevitable bout of negative publicity, which included a broadsheet called L’Anti-Wagner, subtitled Wagner pédéraste.

On opening night at the Éden, hundreds of protesters gathered outside the theater to taunt the audience as it arrived. “La Marseillaise” was sung; whistles were blown; a brick crashed through a window; cries of “À bas Wagner,” “À bas la Prusse,” and “Vive la France” went up. A young blond man who dared to shout “À bas la France” was pursued by an angry crowd, though the police prevented outright violence. Further performances were canceled. Politics was invading everything, Mallarmé wrote—“so much so that even I am talking about it.”

Shortly after the Lohengrin riot, three leading French artists—Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Claude Monet, and Auguste Rodin—attended a banquet in honor of the indomitable Lamoureux. “Your name cannot be missing from this celebration of independent art,” Octave Mirbeau wrote to Rodin in advance. The artists, like the writers, shared an enemy with Wagner: conservative, patriotic, “official” France. Anti-Wagnerism was the sign of a backward mind. Gustave Flaubert indicated as much in his sardonic Dictionary of Received Ideas, which illustrated the philistine mentality: “Snicker when you hear his name and make jokes about the music of the future.” The people who whistled at Tannhäuser in 1861 probably also snickered at Manet’s Déjeuner sur l’herbe and Olympia. When, four years later, Champfleury came upon a group of irate bourgeois at the Olympia exhibition, he pranked them by exclaiming, “It’s Wagner’s nephew!” And when Manet complained about the abuse he was receiving, Baudelaire reminded him that Wagner had endured the same.

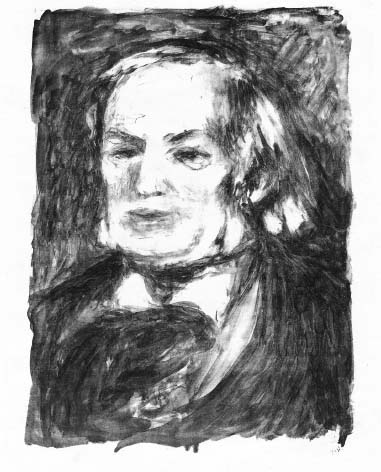

Wagner by Renoir, 1882

Therese Dolan’s book Manet, Wagner, and the Musical Culture of Their Time explores the possible subtext of Manet’s 1862 painting Music in the Tuileries, which shows a distinguished crowd in the Tuileries Garden, listening to music of unseen origin. On the left-hand side are Baudelaire, Champfleury, Théophile Gautier, and Fantin-Latour, all vocal Wagnéristes. Offenbach, satirist of the “music of the future,” is on the right. Faces are occluded in shadow, becoming like masks, and human figures toward the back are almost indistinguishable from trees and vegetation. Dolan surmises that Manet’s turn toward abstraction in this canvas was partly a response to the radical sensibility that Baudelaire detected in Wagner and displayed in his own work. Unsurprisingly, Music in the Tuileries stirred up the same kind of vituperation that had greeted Tannhäuser the previous year. Wagner’s music is unlikely to be playing in this placid outdoor setting, yet a certain edginess in the composition makes one wonder. The Wagnéristes, somber and watchful, look ready for a fight.

Partisans of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist painting often used Wagner as a reference point. The poet Jules Laforgue likened the “thousand little dancing strokes” of Monet and Pissarro to “a symphony which is living and changing like the ‘forest-voices’ of Wagner’s theories, competing vitally for the great voice of the forest.” The composer himself had conservative taste in the visual arts, and late in life he scoffed at Impressionists who “paint nocturne-symphonies in ten minutes.” Nonetheless, in 1882 he consented to sit for a portrait by Renoir—a pallid, ghostlike image, very unlike the stern patriarch seen in German painting. The session took place in Palermo, immediately after the completion of the score of Parsifal.

The first avowed Wagnerian among French painters was Henri Fantin-Latour, who won fame for his lustrous still lifes but harbored higher ambitions. Having fallen for the composer even before the Théâtre-Italien concerts of 1860, Fantin spent decades trying to capture the music dramas on canvas and paper. His first efforts depicted the Venusberg: a nude goddess drapes herself over a dour, black-clad Tannhäuser while nymphs gyrate in an almost Monet-like blaze of sunlight. After a visit to Bayreuth in 1876, Fantin set about evoking the Ring in various media—at least forty works in all. In the pastel Les Filles du Rhin, later redone in oils, the Rhinemaidens are at play in the primeval waters, sunlight filtering down and irradiating their bodies. In Scène finale de la Walkyrie, an indistinct, shrouded Wotan towers over a ridge of fire. The art historian Corrinne Chong relates Fantin’s “aesthetic of vagueness” to the phantasmagoria of diffused sound and onstage steam that the painter witnessed at Bayreuth.

Cézanne’s Wagnerism crested during his “Romantic period” of the sixties, when themes of murder, rape, and decadent coupling preoccupied him. The German musician Heinrich Morstatt, a friend in Marseille, stoked the painter’s interest. “You will make our acoustic nerve vibrate with the noble tones of Richard Wagner,” Cézanne wrote to Morstatt in 1865. Cézanne’s 1868–69 painting Young Girl at the Piano, which now hangs in the Hermitage, was originally known as Overture to “Tannhäuser.” It shows a young woman playing a parlor instrument while an older woman, perhaps her mother, sews reflectively. The picture is outwardly composed and restrained, seemingly at odds with its Wagnerian source. A previous version, now lost, was evidently wilder in style. A friend of Cézanne’s spoke of the painting’s “overwhelming power” and said that it was “as much about the future as Wagner’s music.” Scholars and critics have debated this apparent retreat on Cézanne’s part. André Dombrowski argues that the painter was commenting on the domestication of music, its reduction to a leisurely pastime on the level of embroidery. Mary Tompkins Lewis sees a residual theatrical heat in the twisting patterns of the wallpaper. Indeed, tonal lurches in the composition give a sense of strong emotions beneath the surface.

If Lewis is right, the Venusberg informs two other Cézanne works from around 1870: Baigneuses, an early try at a favorite scene of women bathing; and Pastorale (Idylle), another tableau of nude female figures by the water. Both paintings are gloomy, obscure, drenched in nocturnal blue. In the first, Lewis sees a near-abstract impression of the Venus grotto, modeled on Fantin-Latour: vertical shapes on the left-hand side could be stalactites. In Pastorale, Lewis discerns Tannhäuser dressed in black, reclining in “melancholic reverie.” What is arresting about Pastorale is that Cézanne introduces two other males, both facing away from the viewer. All three men are fully clothed, as in Manet’s Déjeuner sur l’herbe. They seem almost indifferent to the female nudity around them. It’s as if spectators at a Tannhäuser performance have wandered into the mythological orgy, in a posture of jaded arousal.

Where Cézanne reacted to Wagner in muted hues, Vincent van Gogh, a Dutchman who reached his vertiginous zenith in France, associated the composer with explosions of color. In Arles, van Gogh spoke about the resonance he felt between “our color” and Wagner’s ripe chords: “By intensifying all the colors one again achieves calm and harmony. And something happens as with the Wagner music which, performed by a large orchestra, is no less intimate for that.” Van Gogh had heard Wagner performed in Paris and had studied a compilation of his writings. These encounters left the painter with the sense that music had pulled ahead of the other arts. To Gauguin he wrote: “Ah! my dear friend, to make of painting what the music of Berlioz and Wagner has been before us … an art of consolation for broken hearts! There are as yet only a few who feel it as you and I do!!!” And to his brother Theo: “What an artist—one like that in painting, now that would be chic. This will come.” The brazen yellows of Sunflowers and the inundating blues of Starry Night proclaim the arrival of just such an art.

For Gauguin, finally, Wagner stood as a paragon of artistic conviction—an empowering example for the artist’s quest for pure worlds beyond the reach of civilization and commerce. In 1889–90, Gauguin spent time in the Breton village of Le Pouldu, in the company of Paul Sérusier and Jacob Meyer de Haan. The group decorated their inn with pictures and slogans, ranging in theme from the earthy-folkish to the philosophical-mystical. On one wall, beneath de Haan and Gauguin’s frescoes of Breton women scutching flax, Sérusier inscribed a quotation from Wagner, in emerald-green paint: “I believe in a last judgment where all who have dared to profit in this world from sublime and chaste art, all who have soiled and degraded it with the baseness of their sentiments, with their vile greed for material pleasures, will be condemned to terrible suffering.” The same passage, an inexact citation of Wagner’s 1841 story “An End in Paris,” appears in a document known as “le texte Wagner de Gauguin.” As for Wagnerian motifs in Gauguin’s work, hard evidence is lacking, but art historians have compared his ondines to the Rhinemaidens, the female nude of The Loss of Virginity to Brünnhilde on her rock, and the Flageolet Player on the Cliff to the shepherd’s song in Tristan.

By century’s end, genuflections toward Wagner were routine among French painters. Georges Seurat is said to have chosen wider, darker frames for his canvases in imitation of the dramatic blackouts at Bayreuth. The teenaged Paul Signac painted the names “Manet—Zola—Wagner” on the prow of a canoe that he paddled in the Seine. Maurice Denis compared the color contrasts of the Mona Lisa to the instrumental effects of the Tannhäuser overture. Circa 1900, the scandal around Wagner in France had subsided, but the composer’s triumph over opposition did not diminish his legend. Instead, his unstoppable march from the fringe to the center served as the greatest extant demonstration of a successful avant-garde—the victory for which even the most anticommercial artists yearned.