Полная версия:

Wagnerism

The London Wagner Festival of 1877 was a grand affair, consisting of eight concerts at the Royal Albert Hall. The plan was to recoup the deficit created by the first Bayreuth Festival. Although receipts fell short of expectations, the visit was otherwise triumphant. According to the young George Bernard Shaw, Wagner met with “tempestuous applause” at each concert, and at one he received a laurel wreath. The Prince of Wales, more Wagnerian than his mother, attended. Young dandies sought to show that they were “well up in Wagnerism.” Young women felt the slightly illicit thrill of “The Ride of the Valkyries”—or the “Walkers’ Ride,” as Mary Gladstone, the prime minister’s daughter, called it. The press amused itself. Punch declared that after each concert “special trains will run from the Kensington High Street station to Colney Hatch, Hanwell and Earlswood”—lunatic asylums on the outskirts of London.

It helped that Londoners were finally seeing Wagner’s operas complete: The Flying Dutchman in 1870, Lohengrin in 1875, Tannhäuser in 1876. (All were sung in Italian, the standard operatic language of the day.) The Carl Rosa Opera Company, founded by a widely traveled German-Jewish conductor and impresario, had great success with an English-language Dutchman. The public was learning to listen in a new way, as The Musical Times advised: “The Teutonic element in the house had a marvellous effect in teaching the audience that ‘Lohengrin’ was not to be judged by the ordinary standard; so when the usual round of applause was given for the favourite singers on their entrance … a very decided ‘hush’ convinced the astonished Opera habitués that the vocalists must be considered as secondary to the work they were interpreting.” Even J. W. Davison cut back on his vitriol. In a report from Bayreuth, he admitted that the Ring was an “incontestable success.”

Two German immigrants had painstakingly prepared for this breakthrough. One was the pianist and teacher Edward Dannreuther, a native of Strasbourg who spent much of his boyhood in Cincinnati, Ohio, where his father ran a short-lived piano business. He came to London in 1863 and began publishing articles in which he criticized the “phantasmagoria” of French and Italian opera and lauded Wagner’s Beethovenian breadth. By invoking Beethoven, the composer’s supporters catered to the Victorian regard for the improving properties of instrumental music. Wagner, too, occupied an “ideal sphere,” following the “loftiest aspirations.”

Dannreuther’s co-conspirator was Francis Hueffer, born Franz Hüffer, who had arrived in England in 1869, at the age of twenty-four. A classmate of Nietzsche’s in Leipzig, Hueffer had spoken for Wagner’s merits at a time when Nietzsche still had doubts. In London, Hueffer established himself as a Wagnerite music critic, and within a decade he had replaced Davison at the Times. Like Dannreuther, Hueffer had a knack for uncovering Victorian virtues in his subject. His 1874 book Richard Wagner and the Music of the Future praises the composer for his “unequalled firmness and presence of mind” and for the “middle-class freedom and intelligence” of the character of Hans Sachs. Where Baudelaire, listening to Lohengrin, is swept away in abstract ecstasy, Hueffer thinks of angels in white clouds. Sealing Hueffer’s naturalization of Wagner is the dedication of his book Half a Century of Music: “TO HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN, THE FRIEND OF MENDELSSOHN, AND THE FIRST ENGLISHWOMAN TO RECOGNISE THE GENIUS OF WAGNER.”

Both expatriates formed alliances to the artists and writers of the Pre-Raphaelite circle. In 1871, Dannreuther married Chariclea Ionides, daughter of the Greek merchant Alexander Ionides, who hosted salons in his homes and hired the likes of William Morris to decorate them. During his 1877 visit, Wagner was a contented guest at the Dannreuther-Ionides house. Hueffer married Catherine Madox Brown, younger daughter of the Germanically inclined painter Ford Madox Brown. Their son would find literary fame under the name Ford Madox Ford. Dannreuther and Hueffer also knew Swinburne, and composed songs on his poems.

Part of the émigrés’ plan for the 1877 festival was to facilitate meetings between the Wagners and Britain’s leading artists and writers. To that end, the painter John Everett Millais and his wife, Effie Gray, organized a dinner in the Meister’s honor. They were crestfallen when he failed to appear. Cosima, who spoke fluent English, was more sociable. She sat for a portrait by Edward Burne-Jones and asked to meet Morris, because he “treated the same subjects that her husband had treated in his music.”

Cosima also attended a reception for the Grosvenor Gallery, a showplace for Pre-Raphaelitism and Aestheticism, which opened the day the Wagners arrived. The young Oscar Wilde remarked on the conjunction in the Dublin University Magazine: “That ‘Art is long and life is short’ is a truth which everyone feels, or ought to feel; yet surely those who were in London last May, and had in one week the opportunities of hearing Rubinstein play the Sonata Impassionata, of seeing Wagner conduct the Spinning Wheel Chorus from the Flying Dutchman, and of studying art at the Grosvenor Gallery, have very little to complain of as regards human existence and art-pleasures.” Wagner did not, in fact, conduct the Spinning Chorus, but the point generally holds.

Eliot, who frequented Pre-Raphaelite circles, was a constant presence at the Wagner Festival. The music continued to fascinate her, nagging hesitations notwithstanding. She reportedly wept over the scene between Siegmund and Brünnhilde in Walküre. She and Lewes were in attendance when Wagner read aloud his recently completed Parsifal libretto at Dannreuther’s—a riveting two-hour performance, according to several witnesses. The man himself left Eliot cold. He had the personality of an “épicier,” a grocer, she said. Cosima, on the other hand, was a “rare person,” even a “genius.” Cosima returned the admiration, recording in her diary that Eliot had made “a noble and pleasant impression.” The two women sat together at rehearsals while Wagner yelled at the orchestra. Lewes later encouraged Cosima to read a pamphlet titled George Eliot und das Judenthum, the work of a Jewish theologian.

The hoped-for meeting of minds never quite came about. Wagner’s politics and personality may have been stumbling blocks, but the deeper problem was one of cultural ownership. The Pre-Raphaelites saw the stories of Tristan and the Knights of the Grail as their own possession, and tended to look on Wagner as an interloper. Even when they acceded to his power, they did so with a slight grimace. Hence Burne-Jones, in 1884: “I heard Wagner’s Parsifal the other day—I nearly forgave him—he knew how to win me. He made sounds that are really and truly (I assure you, and I ought to know) the very sounds that were to be heard in the Sangraal Chapel.”

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, which sought to revive the handcrafted aesthetic of the Middle Ages in anticipation of a better world, formed in 1848, in the midst of the pan-European wave of revolutionary agitation that also spawned the Ring. The young men at the core of the group—Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and William Holman Hunt—held back from direct political action, but they sympathized with the working-class Chartist demonstration of April 1848. The first Holman Hunt painting to carry the designation “P.R.B.” was Rienzi Vowing to Obtain Justice, a brightly austere canvas in which the Roman populist Cola di Rienzo is seen raising a defiant fist over his brother’s body. For Holman Hunt, as for Wagner and many other leftists, Rienzi symbolized the long struggle for political liberation. The painter intended an “appeal to Heaven against the tyranny exercised over the poor and helpless … ‘How long, O Lord!’”

Morris and Burne-Jones gravitated toward the Pre-Raphaelites while studying at Oxford in the mid-fifties. They were disciples of John Ruskin, who prized the craftsmanship of Gothic architecture and decried the “degradation of the operative into a machine.” The Pre-Raphaelites, too, believed in the Gospel of Work, but only when workers could take pleasure in their tasks. Morris soon emerged as the most audacious thinker in the Brotherhood, applying himself in a variety of media—painting, poetry, fiction, essays, decorative arts, textiles—in pursuit of social reform. He was the principal force behind the Arts and Crafts movement, which sought to restore wholeness and richness to the drab decor of daily life. “The leading passion of my life has been and is hatred of modern civilisation,” Morris later said. Swinburne, a slightly younger Oxfordian, entered the circle around 1857, his tastes more Continental in orientation.

This brand of progressive nostalgia is not unlike Wagner’s own blend of revolution and reaction. The composer felt that the lusty expressivity of the late medieval and early Renaissance periods had given way to artifice and mannerism, and that the artwork of the future should bring back lost unities. For the Pre-Raphaelites, too, the revivification of an idealized past implied a direct attack on an ugly, iniquitous present. The vivid color schemes and quasi-photographic perspectives of Pre-Raphaelite painting—the aroused crouch of Holman Hunt’s The Hireling Shepherd, the blissed-out gaze of Millais’s The Bridesmaid, the flatly sexual stares of Rossetti’s Venus Verticordia and Astarte Syriaca—bring to mind the hedonistic harmonies of Wagner’s Venusberg and his Tristan love scene. And the luminous Holy Grail sonorities of Lohengrin and Parsifal are akin to Burne-Jones’s pale knights and prayerful maidens.

The narrative of Tannhäuser and the Venusberg was known to English-readers through Carlyle’s translation of the Ludwig Tieck poem “The Trusty Eckart,” which Wagner also read. But the Pre-Raphaelites happened to take a sudden interest in the material around 1861, the year of Tannhäuser in Paris. First, Burne-Jones made a watercolor titled Laus Veneris (The Praise of Venus). Not long after, Swinburne set to work on a poem with the same title. Morris began a poem called “The Hill of Venus,” which eventually appeared in his 1870 cycle The Earthly Paradise. Burne-Jones prepared illustrations for Morris’s poem and then revisited the subject in darkly glowing oils. The Tannhäuser scandal, together with Baudelaire’s impassioned response, probably helped to drive interest across the Channel.

Swinburne may well have learned of Wagner through Baudelaire. He was the first British writer to take serious notice of Les Fleurs du mal, reviewing it in 1862. The following year, he traveled to Paris in the hope of meeting his idol. He failed to do so, but happened to see Fantin-Latour’s rendering of the Venusberg in Manet’s studio. Baudelaire later sent Swinburne a letter of gratitude, in which he repeated what Wagner had said to him about the Tannhäuser essay: “I would never have believed that a French writer could so easily understand so many things.” In the same spirit, Baudelaire was amazed that an Englishman had comprehended him. By a quirk of fate, this letter never reached its destination; the photographer Nadar neglected to deliver it, and it surfaced only after Swinburne’s death. Baudelaire also mailed a copy of his Wagner essay, and this did show up at Swinburne’s door—a cryptic message from one poet to another.

Swinburne was already at work on Laus Veneris. From the start, his personal obsessions colored his approach to the legend—the pleasure of pain, the pain of pleasure, a queasy eroticism that borders on sadomasochism:

Asleep or waking is it? for her neck,

Kissed over close, wears yet a purple speck

Wherein the pained blood falters and goes out;

Soft, and stung softly—fairer for a fleck …

Inside the Horsel here the air is hot;

Right little peace one hath for it, God wot;

The scented dusty daylight burns the air,

And my heart chokes me till I hear it not.

The last lines recall Baudelaire’s picture of the Venusberg, “breathing a perfumed but stifling atmosphere, lit by a rosy light which came not from the sun.” They also echo Swinburne’s own description of Les Fleurs du mal: “It has the languid lurid beauty of close and threatening weather—a heavy heated temperature, with dangerous hothouse scents in it.” Swinburne later recommended that anyone wishing to understand his conception of Venus should read the passage of Baudelaire’s Tannhäuser pamphlet that depicts the “fallen goddess, grown diabolic among ages that would not accept her as divine.” This unapologetically erotic, paganistic poem caused a scandal of its own when it appeared in Swinburne’s 1866 collection Poems and Ballads. Accused of “Greek depravity” and “schoolboy lustfulness,” Swinburne cited Baudelaire and Wagner in his defense.

Burne-Jones’s Laus Veneris, the final version of which showed at the Grosvenor in 1878, is a sumptuous snapshot of Venus in repose. She reclines in a full scarlet gown, her right arm dangled behind her head, her eyes disaffectedly drifting down. Four female attendants prepare to sing for her, music being the preferred mode of seduction in Venusberg tales. On the music stand is an illuminated score titled “Laus Veneris.” At the top of the canvas, a window opens to a cool, blue world outside, where five young knights are riding by. The middle one stares in with particular intensity; he might be Tannhäuser. The scene has a hothouse stillness. As often in Pre-Raphaelite work, a present-tense immediacy burns through the veneer of the faux-ancient, setting up unstable resonances between past and present, the imaginary and the real.

Among Pre-Raphaelite visions of the Venusberg, Morris’s “The Hill of Venus” is closest to Wagner in mood. At the outset, the knight wanders the world in cynical despair. Hope flickers in him when he sees Venus’s grotto, and narcissistic rapture overtakes him: “For this, for this / God made the world, that I might feel thy kiss!” After a time, though, he wearies of that ever-burning love, and begins to fear the fires of hell. He makes his pilgrimage to Rome, seeking absolution. Before the Pope, he again grows defiant, and mercy is denied. At the end comes a finely calibrated moral twist: after the knight slinks back to the hill, the Pope loses confidence in his judgment and asks whether he has done wrong. Suddenly, his staff blooms, signaling a miraculous forgiveness that stems from older powers within the earth. There is a taste of the atmosphere of Parsifal: Christianity and paganism reconciled in a Good Friday Spell.

No wonder Cosima Wagner expressed a desire to meet Morris: his universe overlapped with her husband’s to a remarkable degree. He wrote of Venus and Tannhäuser; he painted Iseult; he treated the world of the Grail; he pored over the Icelandic sources that furnished much of the material of the Ring. In the sixties and seventies, Morris studied Old Norse with the Cambridge-based scholar Eiríkr Magnússon, who collaborated with him on an English translation of the Vǫlsunga saga. Morris saw this as “the Great Story of the North, which should be to all our race what the Tale of Troy was to the Greeks.”

Yet Morris loathed the very idea of Wagner. On receiving an English version of Walküre, in 1873, he said that it was “nothing short of desecration to bring such a tremendous and world-wide subject under the gaslights of an opera.” He apparently never heard Wagner’s music in person. If he had, he might have felt the same as Ruskin, who described Meistersinger as “clumsy, blundering, boggling, baboon-blooded … sapless, soulless, beginningless, endless, topless, bottomless.” In the same year that the Ring premiered, Morris composed a four-book epic titled The Story of Sigurd the Volsung and the Fall of the Niblungs. Jane Susanna Ennis, in a comparative study of Morris’s and Wagner’s texts, speculates that Sigurd “would have been very different—indeed, may not even have been written at all—had it not been for Wagner’s Ring.”

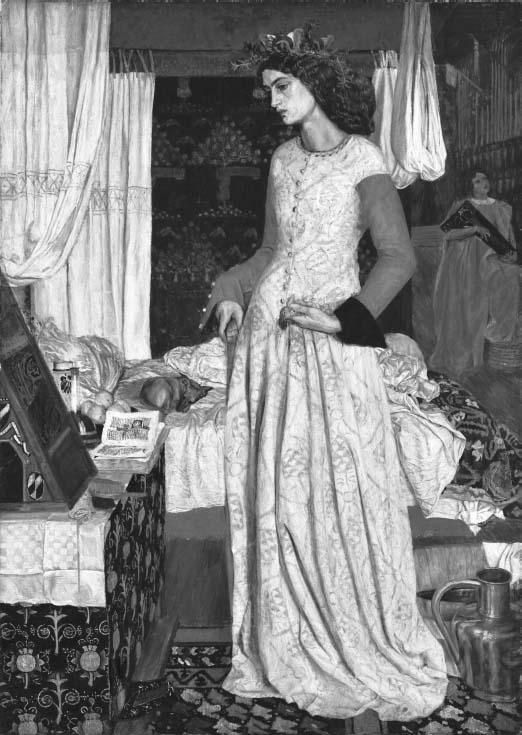

William Morris, La Belle Iseult

Every telling of the Siegfried story hinges on the scene in which the young hero discovers Brünnhilde—or Brynhild, in Morris’s spelling—within her aerie of fire. Morris and Magnússon, in their version of the Vǫlsunga saga, interpolate a passage from the Poetic Edda and translate it fairly faithfully:

Long have I slept

And slumbered long,

Many and long are the woes of mankind …

Hail to the day come back!

Hail, sons of the daylight!

Hail to thee, dark night, and thy daughter!

Wagner, too, stays close to the Edda text. It falls to the orchestra to conjure the majesty of the scene—the first harsh glint of the sun (E minor) followed by the warming spread of its rays (harp-caressed C major).

Hail to you, sun!

Hail to you, light!

Hail to you, light-bringing day!

Long was my sleep;

awakened am I;

who is the hero

who woke me?

Morris, in Sigurd, casts Brynhild’s hymn to the sun in more flowery terms, as if trying to compensate for the orchestral resources of the German rival:

But therewith the sun rose upward and lightened all the earth,

And the light flashed up to the heavens from the rims of the glorious girth;

But they twain arose together, and with both her palms outspread,

And bathed in the light returning, she cried aloud and said:

“All hail, O Day and thy Sons, and thy kin of the coloured things!

Hail, following Night, and thy Daughter that leadeth thy wavering wings!

Look down with unangry eyes on us today alive,

And give us the hearts victorious, and the gain for which we strive! …”

Hueffer and Shaw considered Sigurd a worthy counterpart to the Ring. But the plainer, more pungent language of Morris’s earlier translation has aged better.

Wagner and Morris differ most in their valuation of past and present. Morris often frames his legendary world as a lost paradise. Sigurd begins: “There was a dwelling of Kings ere the world was waxen old.” The same elegiac voices speak at the end of the Brynhild chapter: “They are gone—the lovely, the mighty, the hope of the ancient Earth.” In The Earthly Paradise, Morris bids the reader to “Forget six counties overhung with smoke, / Forget the snorting steam and piston stroke, / Forget the spreading of the hideous town.” Wagner avoids that tone of “Once upon a time.” In the preludes to Tannhäuser, Lohengrin, and the Ring, a distant world is materializing out of the mist, yet it is soon overcome by the illusion, exciting and dangerous, of the past bleeding into the present. Wagner removes the gilt border around the stuff of myth.

The tale of Tristram and Iseult is indisputably a property of the British Isles, even if the earliest surviving versions come from twelfth-century France. Iseult the Fair is an Irish princess, her castle thought to lie on the outskirts of Dublin. King Mark, to whom she is betrothed, has a castle in Cornwall, often identified with Tintagel, where King Arthur is said to have been conceived. Tristram, the Breton orphan, is effectively Cornish, because King Mark has adopted him. By the time Wagner took up Tristan, in the late fifties, he was a latecomer; Morris was painting a fresco of the lovers on the walls of the Oxford Union, and Matthew Arnold had published a three-part poem called Tristram and Iseult. When, many years later, Arnold heard Tristan in Munich, he placidly commented, “I have managed the story better than Wagner.”

Burne-Jones, Tristram and Iseult stained-glass panel

Arnold confines himself to three fragments of the romance. First we see Tristram awaiting his beloved; then the lovers in their last embrace; and, finally, a scene from the lonely life of Iseult of the White Hands, Tristram’s wife in the original legend. (That character is absent from Wagner’s opera.) Despite Romantic touches, Arnold takes a dim view of “this fool passion … an unnatural overheat at best.” Tennyson’s treatment in “The Last Tournament” (1870–71), the gloomiest chapter of his Idylls of the King cycle, is even harsher. Tristram is arrogant and hard-hearted, a player of “broken music,” and Isolt is motivated as much by hatred of her husband as by desire for her lover. The tale ends with jarring abruptness, as Liebestod is reduced to death pure and simple:

He rose, he turn’d, and flinging round her neck,

Claspt it; but while he bow’d himself to lay

Warm kisses in the hollow of her throat,

Out of the dark, just as the lips had touch’d,

Behind him rose a shadow and a shriek—

“Mark’s way,” said Mark, and clove him thro’ the brain.

The Pre-Raphaelites could never be so unsentimental. In Morris’s Oxford Union fresco, Tristram and Iseult clutch each other amid lush vegetation, their love implicitly organic and natural. In the same period, Morris painted La Belle Iseult, with Jane Burden, his future wife, appearing as a pensive queen, her gaze fixed on a book. In 1862, the arts-and-crafts firm of Morris and Co. produced a series of Tristram-and-Iseult stained-glass panels, with Burne-Jones, Rossetti, and Ford Madox Brown making contributions; a tone of noble suffering prevailed.

Swinburne, who felt that Tennyson had “degraded and debased” the romance, sought to put matters right in his long poem Tristram of Lyonesse, begun around 1870 and completed in 1882. Just before embarking on the project, Swinburne studied a collection of Auguste de Gasperini’s writing on Wagner, with its extensive treatment of Tristan. He also conferred regularly with the wealthy Welsh connoisseur George Powell, a vehement Wagnerite who went to Bayreuth in 1876. (During his visit, Powell had tea with Cosima and attempted to interest her in Swinburne’s poetry, apparently without success.) Wagner’s connection to Schopenhauer especially interested the poet as he prepared to leap into the ravishing abyss of the Tristan story.

Morris launches his Sigurd with an image of time revolving backward. Swinburne, in a more Wagnerian maneuver, begins with an incantatory, forty-four-line sentence in praise of love:

Love, that is first and last of all things made,

The light that has the living world for shade,

The spirit that for temporal veil has on

The souls of all men woven in unison,

One fiery raiment with all lives inwrought …

Swinburne admits that love has wrecked those in its path, as “soul smote soul and left it ruinous”; but, unlike Arnold and Tennyson, he still insists on love’s painful joys. Indeed, repeating a motif from Laus Veneris, he proposes that love entails “a better heaven than heaven is.” As in Tristan, the heat of Tristram and Iseult’s ecstasy causes the outer world to dissolve. Binaries break down: day becomes night, night becomes day. When the lovers first kiss, “four lips became one burning mouth.” The carnal oblivion extends to the dimension of sound, as the lovers hear an inner music that drowns out the roar of the sea and, later, festive shouts from the nearing shore. It is hard not to hear this self-deifying music as Wagner’s Tristan score, now swallowed up in poetry’s realm:

Yet fairer now than song may show them stand

Tristram and Iseult, hand in amorous hand,

Soul-satisfied, their eyes made great and bright