Полная версия

Полная версияConstantinople and the Scenery of the Seven Churches of Asia Minor

By means of this aqueduct, the waters were deposited in various cisterns; some open, and some covered, so that the whole city was excavated into exposed or subterranean reservoirs. One great inconvenience attended those that were exposed. The city and vicinity of Constantinople abounded in storks; they were supposed to convey serpents, and drop them in the water, by which it was poisoned, and rendered fatal to those who drank it. The celebrated impostor Apollonius of Tyana, who was reputed to work such powerful miracles, was applied to, by the reigning emperor, for a remedy. By his directions, a pillar called Pelargonium was erected, on the summit of which were three storks fronting each other; and by this talisman the kindred birds were immediately expelled the city, and the salubrity of the waters restored. To commemorate the event, the following epigram was inscribed on the base of the pillar.

On sculptur’d column stands the mystic charm,And guards the fainting citizens from harm.Far fly the storks, to seek the distant wood;And snakes no longer taint the wholesome flood.These cisterns were afterwards filled up with earth, and are now converted into gardens, where the storks, no longer the cause of evil, are invited to return. The Turks evince a particular attachment for them, and erect frame-work like cradles on the tops of their houses, which the birds inhabit and breed in.

Of the covered cisterns, but two remain. One is called Yéré Batan Seraï, or the “Subterranean palace,” and is still filled with water. It resembles a vast subterranean lake, out of which issue rows of 336 marble pillars, of various orders of architecture, supporting an arched roof. The memory of this magnificent watering-palace was altogether lost; the streets passed over it, and the houses above were supplied from it with water, while the inhabitants knew not whence it came. After it had remained unknown to the Turks since the capture of Constantinople, it was discovered by Gillius more than three hundred years ago. A second time it fell into oblivion among this incurious people, till it was searched for, and again found a few years since. It was formerly in total darkness, but part of the wall has fallen down, and sufficient light is admitted to examine it. A boat, or raft, is moored to one of the pillars, in which strangers are permitted to embark, and explore its dim recesses; and marvellous stories are told by the Turks of the fatal end of those bold adventurers.

The second cistern is no longer employed as a reservoir for water. It lies beneath an open area in the vicinity of the Atmeidan, and is converted into a silk manufactory by a number of industrious Jews and Armenians. The Turks have named this subterranean palace Bin-bir-derek, in allusion to its supposed original number of columns, 1001, although 212 are all that can now be distinguished. Each column is said to consist of three shafts with their respective capitals, but the lowest is, at present, buried beneath the material of the flooring. The whole enclosed area occupies 20,000 square feet, and is capable of containing 1,237,000 cubic feet of water, a quantity sufficient to supply the population of Constantinople for fifteen days.

The pillars of this cistern are distinguished by monograms deeply cut on the shafts and capitals, like hieroglyphics on an Egyptian obelisk, and so obscure as equally to puzzle the learned. One of them consists of the Greek initials for Euge philoxene, “Hail, thou strangers’ friend.” This cistern, under the Greek empire, was decreed to be public for the use of all strangers, and was therefore called philoxenos.

THE SOLIMANIE, OR MOSQUE OF SULTAN SOLIMAN.

FROM THE OUTER COURT

T. Allom. H. Adlard.

The Franks have so changed the terms of the Turkish language, that they are hardly to be recognized. Moslem, which signifies a “professor of the true faith,” they have corrupted into Mussulman; and Mesjid, the temple in which he worshipped, into mosque!

When the Turks appropriated to themselves the great Christian church of Santa Sophia, they made it the model of all their future religious edifices. The general outline is a Greek cross, enclosed in a quadrangle. This is surmounted with a large dome in the centre, to represent, as the modern Greeks say, the great wound in our Saviour’s side; the four smaller domes at the angles, depicting the smaller wounds in his hands and feet. This form the Turks usually observe, without any reference to its origin; but they have added members peculiar to themselves. They hold bells in abhorrence, and invite their congregations to prayer by the human voice only. For this purpose certain slender towers shoot up from the angles of the edifice, where the Muezzim ascends by interior stairs, and from a circular gallery round the shaft calls together the faithful. These towers are denominated Menar or Minareh, an Arabic word which signifies a “beacon or light-house” to guide the true believer. The Muezzim puts his hands behind his ears, and from the hollow of his palms shouts out his invitation, walking round and repeating to the four points of the compass, “There is but one God, and Mohammed is his prophet:−come to prayers−come to salvation.” This cry, called the Ezan, is repeated five times a day at regular intervals; and as it issues from every minaret, and perhaps two thousand mouths at the same moment, it fills all the air with a solemn and supernatural sound, and regulates all the arrangements of the people, who have no public clocks to direct them. Besides the common mosque of the city, there are thirteen eminently distinguished. They are called Djami Selatyn, or “Imperial mosques,” because they have been erected by some sultan as the highest act of piety. They are always distinguished by their magnitude, magnificence, and the number and beauty of their minarets. While the smaller mosques have but one, they have never less than two, and generally four. But of all these Djami, that erected by Soliman II. is the most splendid among the mosques, as its founder was among the sultans. He was called “the magnificent,” and his temple justifies the appellation. The Christian church of Saint Euphemia, at Chalcedon, in which the grand council had been held, was celebrated for its size and architectural ornaments. It contained on that memorable occasion 630 bishops in its nave, and was the most distinguished of Christian churches after Santa Sophia: when that edifice was dedicated to the Prophet by his predecessor, Soliman could not appropriate any of its parts to his new erection; so he dilapidated the church of St. Euphemia for the purpose, and built his mosque with its materials. It was commenced in 1550, and took five years to build it.

It would be difficult to convey, by any description, a perfect idea of a building so vast and complicated. A notice of its prominent features must suffice. It is a quadrangle, 234 feet long, and 227 wide. The great dome by which the edifice is surmounted, is flanked or supported by two hemispheres, one on each side, and over each aisle are four smaller ones. A broad flight of marble steps leads to the great door, before which is a façade, which particularly distinguishes this temple. It consists of six pillars of Egyptian porphyry, of immense size and singular beauty. Attached to the edifice are four minarets in front and rear, having galleries ornamented with tracery; and by a singular irregularity, two, having but two galleries, are shorter than the others which have three. Beside it are splendid mausolea, surmounted with domes, under which repose the bodies of the founder and his Sultana. At the head stands a knob covered with his turban, richly ornamented with precious stones, and near it is suspended the Alcoran, from which an Imaum reads a daily portion, for the consolation of him whose ashes repose in the tomb, and who is supposed to hear it. Over one of the gates is an inscription recording its erection. It states that it was built by “the glorious Vicar of Allah, existing by the authority of the mystic Koran, the tenth of the Ottoman emperors, for the faithful people who served the Lord.” It concludes with a prayer, “That the imperial race may never be interrupted on earth, and enjoy eternal delights prepared in paradise.”

This mosque, like most others, is surrounded by two areas; one of which, planted with trees, is a common thoroughfare usually filled with groups of people. Here soldiers sometimes encamp, and men of war pitch their tents within the precincts of the mussulman’s God of peace. Here, also, small merchants expose their wares, and no one casts out those who “buy and sell.” Here even a Giaour may pass unobstructed, and the infidel hat be seen mixed with the sacred turban.

THE MOSQUE OF SULTAN ACHMET

T. Allom. E. Goodall.

The monarch who erected this mosque, ascended the throne in the year 1603, and at the age of fifteen. He was immediately afterwards seized with the small-pox, and, in order that the janissaries might not avail themselves of his illness, he caused his own brother to be strangled, having first put out his eyes. His object was to deprive the turbulent soldiers of every pretext for dethroning him, as they were disposed to do, when there existed no another of the line of Mohammed to succeed him. His next act was to build a mosque, as fratricide is no impediment to Turkish piety; and it is remarkable, that in this mosque, two centuries afterwards, was the utter extirpation of these janissaries effected.

He was determined that it should exceed in beauty that of Santa Sophia, or the great Solimanie, so he ordered that it should be distinguished by six minarets. When this design was communicated to the Mufti, he represented to the Sultan the impiety of such an act, as the mosque of the Prophet at Mecca had but four, and no sacred edifice since built had presumed to exceed that number. Achmet assured the Mufti that he must be mistaken, and immediately summoned a Hadgee, who had just made the pilgrimage to Mecca, into his presence, who affirmed that he had himself seen and reckoned the six minarets; and, to satisfy entirely the Mufti’s scruples, a caravan of pilgrims were directed to proceed to the tomb and temple of the Prophet, and make their report. Meantime the Sultan despatched a Tatar, who was to travel night and day, with orders to the Sheik Islam, that two new minarets should be immediately added to the temple; and when the slow caravan arrived, they found the number to be what the Sultan had stated−and reported accordingly. Achmet now pushed on his building with indefatigable activity, and in order to expedite it, he worked at it himself with his own hands, devoting one hour every Friday after prayers to the employment, and then paid his fellow-workmen, every man his wages, in order by his personal example to stimulate their exertions.

The site he selected was the most admirable and commanding which the city afforded. It forms one side of the Atmeidan, and is separated only by an open screen from this extensive area, one of the few open spaces within the walls of Constantinople. From this it is seen to great advantage on one side; while on the other, towering over the gardens of the Seraglio, and surmounting the lofty hill on which it stands, it is the most conspicuous object presented to a stranger approaching from the Sea of Marmora, and gives the first and most favourable view of those imperial edifices. The materials selected were of the most costly kind, in so much, that it is affirmed that every stone in the edifice cost three aspers. It stands in an open space, which forms round it an extensive ambulatory, from the latter of which the edifice arises, and is seen to more advantage than any other in the city.

The first objects that strike the spectator are the six beautiful minarets, with their elegant and slender forms ascending to an immense height, and seeming as it were to pierce the clouds with their sharp-pointed cones. Round each run three capitals or galleries for the Muezzim, highly ornamented in fretted arabesque. Above these appears the majestic edifice swelling into domes and cupolas, and covered with light tracery and fancy fretwork, forming a strong contrast to the comparatively heavy, dark, and dismal dome of Santa Sophia, which rises at no great distance beside. This juxtaposition strikes a stranger. He sees with surprise that the genius of a dull and ignorant Turk should produce an edifice so superior in beauty and elegance to this chef-d’œuvre of Grecian art. Architects of that nation had been employed in erecting the imperial mosque of Mohammed II. and Selim II., but this of Achmet is exclusively Turkish or Arabic architecture.

The summit of the edifice is distinguished by thirty cupolas, from whence ascends the great dome, flanked by four semi-domes. The mosque is entered by massive brazen gates, embossed in high relief, and the interior presents a view of the dome supported by four gigantic columns, fluted and filleted, round which are inscribed, in bands, sentences from the Koran. The walls are richly painted in fresco with more variety than regularity, and gilded tablets on them every where display Arabic inscriptions. The light is admitted by windows of stained glass, thickly studded in small compartments, which look exceedingly rich, casting a soothing and a religious, but yet ample light; for this mosque is distinguished above all others in this respect, that by the construction and arrangement of the casements, the interior is fully illuminated, which forms a strong contrast to the dim and doubtful twilight admitted into most other religious edifices of the East.

Between the pillars is a large circle of wire-suspended lamps, which does not add to the general effect; globes of glass, ostrich eggs, and other frivolous and mean ornaments, frequently deform the interior of those noble buildings, and mark the genius of a Turk−at once puerile and magnificent. There is, in other respects, a noble simplicity, a naked grandeur, well befitting a worship from which all idolatrous representations are excluded. The interior of a mosque resembles the nave and transept of St. Paul’s, with the exception of its statues−grand and noble by its vastness and vacuity.

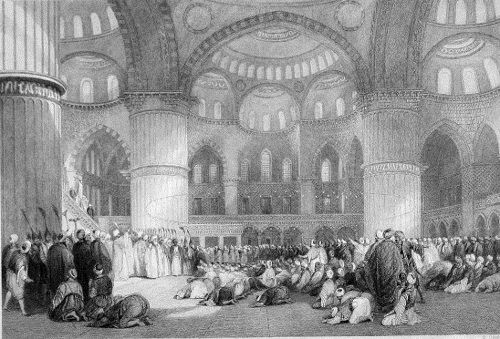

The occasion chosen by the artist, in the illustration, exhibits a display of the most important circumstance that has occurred since the Osmanli established themselves in Europe. It was the moment when it was to be decided, whether they should remain the rude and obstinate barbarians that first crossed the Hellespont, or be illumined by the lights and amalgamated with the nations of Europe, and when the reforming Sultan, struggling for life and empire, was compelled to have recourse to the last expedient left him. The janissaries having the whole population of the city entangled in their connexion, and enlisting all its prejudices on their side, were accumulating such a vast force, as would soon bear down all opposition: but Mahmoud, at once, determined on that course which could alone counteract their influence. He ordered the Sandjak sheriff, or sacred standard of the Prophet, to be taken from its repository in the imperial treasury. This sacred object was only seen on the most solemn and important occasions, and was now, for the first time for half a century, exhibited, and brought with great pomp to the mosque of Achmet. When this was rumoured abroad, there was no man who professed the true faith, that dared to resist the call: thousands and tens of thousands were seen rushing from all quarters to this temple; and when it was filled by the multitude, the standard was displayed from the lofty pulpit of the Imaum. On the steps stood the Sultan, exhorting the people, by the faith they owed the Prophet, now to rally round the sacred ensign. A deep murmur of assent, the strongest display of Turkish feeling and determination, filled the lofty dome. They all fell prostrate in confirmation of their resolve, and from that moment the cause of the janissaries became desperate.

TOPHANA−ENTRANCE TO PERA

T. Allom. R. Sands.

Tophana literally signifies, the place where cannon are deposited, and here are the great foundry and arsenal where they are made and laid up. This establishment is represented on the right of the illustration, by an edifice with pointed windows, admitting light through a number of apertures, and having its roof crowned with cupolas. In front is a spacious quay, constructed along the Bosphorus, and always lined with several ranges of ordnance, which are here scaled and proved, and occasionally used on days of rejoicing, like those formerly on the Tower-wharf at London. There is nothing, perhaps, in which a Turk more delights, than in the discharge of a cannon. It is, therefore, the sound that is heard every day, and almost all day long. It announces the rising and setting of the sun; the birth of a child, and the death of a traitor; the movement of the Sultan in all directions; the opening and closing of the Ramazan and Bayram, and other religious periods. In time of war, the arrival of noses and ears to be piled at the gate of the seraglio, is proclaimed by these cannon; and on occasion of any success, however trifling, the two peninsulas of Pera and Constantinople are shaken to their centre by the explosions.

At the commencement of the Greek revolution, this wharf was nearly fatal to Pera. One of those fires which so constantly devastate the city, broke out here, and extended to Tophana. Towards midnight, the city of Scutari was assailed by showers of balls, and it was instantly rumoured that the fire was caused by the Greeks, who had seized on this depôt, and were directing its cannon against different places. This news was spread to Constantinople, and an immediate insurrection of the janissaries took place. They rushed down to the water to the number of 10,000, and were about to seize the caïques, and pass over to assist their countrymen. They had long waited for an opportunity or pretext for plundering the Greeks; and had this body of exasperated, armed men rushed into a town on fire at midnight, it is probable that not a Frank or Greek would have been left alive in “infidel Pera.” Fortunately, their aga had the water-gates closed in time, and he persuaded them to wait till messengers were sent over to ascertain the fact. They found that all the cannon on the wharf had been left loaded with ball, which the Turks never thought of drawing, and when the fire reached them, they discharged their balls of themselves, which passed across the Bosphorus to Scutari on the other side.

Behind the Tophana is the Eski Djami, or old mosque, to distinguish it from the Yeni Djami, or new one, lately erected by the present Sultan in this district; and on the left, crowning the summit of the hill, are the heights of Pera, covered with the residences of European ministers and merchants; whose houses, the finest in the city, command a magnificent view on all sides of the Bosphorus and Sea of Marmora. These edifices are situated in a street ascending the spine of a ridge, like the High-street of Edinburgh, and approached only by steep narrow passages, like the Wynds of that town. They are so precipitous, that it is necessary to form them into broad steps, to enable a passenger to reach the top.

The Turks are not fond of multiplying names, so they often make one serve for a whole district. Tophana, therefore, includes a large space, altogether unconnected with the cannon foundry. At the base of Pera hill is a low alluvial flat, once overflowed, perhaps, by the waters of the Bosphorus. This has been enlarged by casting upon it all the offals of the cities of Pera and Galata, so that it has encroached upon the harbour. Here are heaps and hillocks of all manner of decaying vegetable and animal substances, festering and dissolving, which continually exhale a cadaverous odour. This attracts the foul animals of the region; packs of savage dogs like wolves or jackals, flocks of kites and vultures in their season, and at all times flights of gulls and cormorants, who almost cover and conceal these heaps with their multitudes, and deafen the ear with their howling and screaming. When gorged with their foul meal, these harpies light upon the roofs of the houses, where they exhibit a singular spectacle−sleeping off the effects of repletion, and waiting again to attack their prey. They enjoy among the Turks such perfect security, that they often light on a caïque, and dispute the possession of it with the passengers.

But what has rendered Tophana so distinguished is, that it is the great point of embarkation, either for the Bosphorus or the Sea of Marmora. In a country where there are no carriages, nor, properly speaking, roads to run them upon, water is the great medium of conveyance. This then is the resort of a continual moving mass, of all nations and costumes. Along the shore, beside a modern slip and platform, light caïques, and the heavier barges of the Princess’ Islands, are in constant attendance. Above is a range of coffee-houses, where the caïquegees sit over their coffee and chiboque till a passenger appears, and they are invited to attend him. The characteristic traits of the people are here strongly marked. The Greek, bustling and shouting, almost forces you into his caïque; the Turk, grave and decorous, seldom utters a word, but merely points to his boat just covered with a rich and fresh carpet. A Hadgee, with a green turban, grey beard, badge, and silver-headed baton, interposes, and lets you choose for yourself, never giving a preference to his own countrymen.

Among the vessels seen here are those singular ships from the Black Sea, before mentioned; their lofty prows and sterns, towering above the water to an extraordinary height, reminding you of the extreme antiquity of their shape, when

High on the stern the Thracian raised his strain,And Argos saw her kindred treesDescend from Pelion to the main.The bold Argonauts brought the first model of a ship into those remote waters, where it has ever since been preserved and imitated.

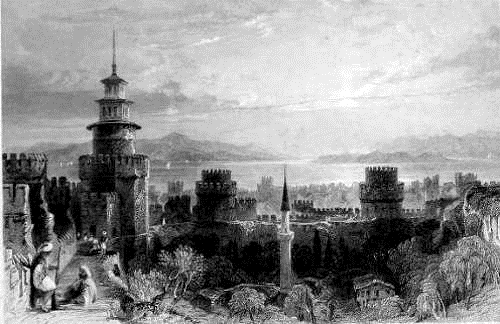

STATE PRISON OF “THE SEVEN TOWERS.”

T. Allom. W. H. Capone.

At the extremity of the land-wall of Constantinople, where it meets the sea of Marmora, rises an enclosure flanked by battlemented towers. It is the first object seen by Frank ships, and thus the stranger is presented with a prospect that reminds him of the most striking and singular usage of Turkish despotism. This enclosure, and the towers, existed under the Greek empire, and were called “Heptapurgon,” from the number of the castles included. They were first erected by Zeno, and enclosed by the Comneni, and were employed as a prison for state offenders. When the Turks took possession of the city, the Sultan appropriated them as a secure place to deposit his plunder. They afterwards reconverted them to their original purpose of a state prison, and added a feature peculiarly their own. The character of an ambassador, held sacred by all other nations, was here violated. The first symptoms of a rupture between the Turks and a foreign state, was, to seize the resident minister, and incarcerate him in this prison; and the European states, instead of revolting against this barbarous outrage on the laws of nations, quietly submitted to it, as they did to the oppression of the Barbary pirates, because each rejoiced, and felt itself elated, at the degradation of the other. Mr. Beaufeu, a French minister, confined there, made his escape; and the Sultan was so enraged, that he immediately caused the governor to be strangled in his own prison. Since then, the Turks are not disposed to admit strangers, lest they might discover the secrets of their prison-house. This barbarous custom continued so late as the year 1784, when the Russian envoy was sent there, as the first act of hostility. The lights and usages of civilized Europe began immediately after to dawn on the East. The just and amiable Selim discontinued the practice, and the present Sultan has abolished it altogether. It was generally supposed the custom would be renewed, and the Sultan would think himself justified in imprisoning the ambassadors of all the powers leagued against him at Navarino, in retaliation for that wanton and unprovoked attack; but he suffered them quietly to depart, and set an example of moderation, and scrupulous regard to the law of nations, which European states might do well to imitate.