Полная версия

Полная версияConstantinople and the Scenery of the Seven Churches of Asia Minor

Among the many fountains which adorn the city, there are two on which the Turks seem to have exerted all their skill in sculpture. One in Constantinople near the Babu Humayun, or “the Great Gate of the Seraglio.” The other in Pera, near Tophana, or the “canon foundry.” They are beautiful specimens of the Arabesque, and highly decorated. That at Tophana, represented in the illustration, is particularly so. It is a square edifice with far-projecting cornices, surmounted by a balustrade along the four façades. These last are covered over with a profusion of sculpture, and every compartment, formed by the moulding, is filled with sentences from the Koran, and poetical quotations from Turkish, Persian, and Arabic authors. The following is a translation of some of the inscriptions. It was erected in 1732.

“This fountain descended from heaven−erected in this suitable place, dispenses its salutary waters on every side by ten thousand channels.”

“Its pure and lucid streams attest its salubrity, and its transparent current has acquired for it an universal celebrity.”

“As long as Allah causes a drop of rain to descend into its reservoir, the happy people who participate in its inestimable benefits, shall waft praises of its virtues to that sky from whence it came down.”

“It should be our prayer that the justice of a merciful God should reward with happiness the author of this benevolent undertaking, and have his deed handed down to a never-ending posterity.”

“This exquisite work is before Allah a deed of high merit, and indicates the piety of the Sultan Mahmoud.”−1145.

The whole of the water department is under the direction of the Sou Nazir, or, “president of water,” who has under him the Sou Ioldgi, or “water engineers,” and the Sacgees, or “watermen.” The business of the first is to watch that the Bendts, &c. receive no damage, and are in constant repair; the second distributes the water over the city. They are supplied with leathern sacks, broad at one end and narrow at the other, somewhat like churns, and closed at the mouth with a leather strap; when it is filled at a fountain, it is thrown across the Sacgee’s back, the broad end resting on his hip, and the narrow on his shoulder; when he empties it, he opens the flap, stoops his head, and the water is discharged into some recipient. There are generally in every hall two vessels sunk in the ground, and covered with a stopper. These the Sacgee fills every day, and receives for his trouble about two paras, or half a farthing.

Around the fountain is the great market, the most busy and populous spot on the peninsula of Pera. It is held between the gate of Galata on one side, and the manufactory of pipes on the other: above is the descent from Pera to the Bosphorus, and below the crowded place of embarkation, so that the confluence of people from these several resorts, creates an almost impassable crowd. Among the articles of sale, the most numerous and conspicuous are usually gourds and melons, of which there are more than twenty kinds, called by the Greek Kolokithia, and by the Turk Cavac. They are piled in large heaps, in their season, to the height of 10 or 15 feet. Some of them are of immense size, of a pure white, and look like enormous snow-balls−they are used for soups: others are long and slender−the pulp is thrust out, and the cavity filled with forced-meat. This is called Dolma, and is so favourite a dish, that a large valley on the Bosphorus is called Dolma Bactche, or the gourd garden, from its cultivation. Another is perfectly spherical, and called Carpoos. It contains a rich red pulp, and a copious and cooling juice, and is eaten raw. A hummal, or porter, may be seen, occasionally, tottering up the streets of Pera, sinking under the weight of an incredible load, and overcome by the heat of a burning sun. His remedy for fatigue is a slice of melon, which refreshes him so effectually, that he is instantly enabled to pursue his toilsome journey. The Turkish mode of carrying planks through their streets is attended with serious inconvenience to passengers. The boards are attached to the sides of a horse in such a manner, extending from side to side of the narrow streets, that they cannot fail of crushing or fracturing the legs of the inexperienced or inactive that happen to meet them. Neither are the dogs, nor their most frequent attitude, forgotten in our illustration. The market-place is their constant resort: there they quarrel for the offals; and a Frank, whose business leads him to that quarter, has reason to congratulate himself, if he shall escape the blow of a plank from the passing horse, or the laceration of his flesh by an irritated dog.

ROUMELI HISSAR, OR, THE CASTLE OF EUROPE.

ON THE BOSPHORUS

T. Allom. R. Smith.

The supposed origin of the Bosphorus is connected with the most awful phenomena of nature; and the lovely strait, which now combines all that is beautiful and romantic, grateful to the eye, and soothing to the mind, owes its existence to all that is fearful and tremendous.−At its eastern extremity, and above the level of the Mediterranean, there existed an inland sea, covering vast plains with a wide expanse of waters, several thousand miles in circumference. By a sudden rupture, it is supposed, an opening was made, through which the waters rushed, and inundated the subjacent countries. For this supposition there are strong foundations of probability. The comparatively small sheets of water now partially occupying the space which the greater sea once covered, under the names of the Euxine, Azoph, Caspian, and Aral seas, are only the deeper pools of this great fountain, which has, in a succession of ages, been drained off, leaving the shallower parts dry land, with all the marks of an alluvial soil. The spot where the great rupture is supposed to have taken place is indicated by volcanic remains: basalt, scoriæ, and other debris of calcination, lying all around. The strait itself bears all the marks of a chasm violently torn open, the projections of one shore corresponding to the indentations of the other, and the similar strata of both being at equal elevations, while the bottom is a succession of descents, over which the water still tumbles with the rapidity of a cataract. The opinions of antiquaries accord with natural appearances. The first land which this mighty inundation encountered was the continent of Greece, over which it swept with irresistible force. Tradition has handed down to us the flood of Deucalion; and ancient writings have assigned as its cause, “the rupture of the Cyanean rocks:” so that both poets and historians concur in preserving the memory of this awful event.

After the first effects of this inundation had ceased, a current was still propelled by the Danube, the Borysthenes, and other great rivers, which pour their copious streams into the Euxine, and have no other outlet: hence it still runs down with considerable velocity. In some places, where the convulsion seems to have left the bottom like steps of stairs, this is dangerously increased. It is possible that the continued attrition of the water, for thousands of years over this rocky surface, has worn it down to a more uniform level; still three cataracts remain, one is called shetan akindisi, or “the devil’s current:” it is necessary, from its laborious ascent, to haul ships up against it with considerable toil. To the ancients it was accounted a perilous navigation, when the broken ledges were still more abrupt. Among the acts of daring intrepidity was deemed the navigation of this strait. Hence Horace says−

“To the mad Bosphorus my bark I’ll guide,And tempt the terrors of its raging tide.”There is not a promontory or recess in all its windings, that is not hallowed by the recollection of either fictitious mythology or authentic history. The ancient name of Bosphorus signifies “the traject of the ox;” the passage being so narrow that such animals swam across it, and hence it is sometimes spelled Bosporos. But the fanciful mythology of the Greeks assigned a more poetic derivation of the name. They assert that Iö, having assumed the form of a cow, to escape the vigilance of Juno, in her solitary wanderings swam across this strait, and consigned to fame the tradition of the event by the name it bears. One promontory preserves the name of Jason, who landed there in his bold attempt to explore the unknown recesses of the Euxine. Another retains that of Medea, for there she dispensed her youth-giving drugs, and conferred upon the place that reputation of salubrity which still distinguishes it. The narrow pass, that divided Europe from Asia, was also the transit chosen by great armies. Here Darius crossed, when the hosts of Asia first poured into Europe, and the rage of conquest led the gorgeous monarch of the East, from the luxuries and splendour of his own court, to penetrate into the rude and barbarous haunts of the wandering Scythians. Here it was that Xenophon, and his intrepid handful of Greeks, crossed over, to return to their own country. Here it was that the Christian crusaders embarked their armies, to rescue the holy sepulchre from the infidels; and here it was that the infidels, in return, entered Europe, and destroyed the mighty Christian empire of the East.

The accompanying illustration exhibits the scene of these events, and so commemorates the deeds of remote and recent ages. The strait is here not more than seven stadia, or furlongs, across; and, as Pliny truly says, “You can hear in one orb of the earth, the dogs bark and the birds sing in the other; and may hold conversation from shore to shore when the sound is not dispersed by the wind.” In particular seasons, during the migration of fish, boats are seen, extending in a continued line, and forming a bridge from side to side. The rock on which Darius sat is still pointed out; and, if a stranger occupy the rude seat at such a moment, it will powerfully recall to his imagination those times when mighty armies crossed and recrossed on a similar fragile footing.

The events connected with Roumeli Hissar, or the Castle of Europe, are of surpassing interest. When the fierce Mahomet determined to extinguish the feeble Roman empire, and transfer the Moslem capital to a Christian soil, he found two dilapidated towers, one in Asia, and the other in Europe, which had been suffered to fall into utter decay. He re-edified that on the Asiatic shore, and, having been allowed to do this without opposition, crossed over and rebuilt the European castle also, so as completely to command the navigation of the straits, by occupying two forts on the most prominent points of the nearest parts of it. When the emperor remonstrated against this violation of his territory, he was tauntingly but fiercely answered, that “since the Greeks were not able to protect their own possessions, he would do it for them;” and he threatened to slay alive the next person who came to remonstrate. To establish his usurped right, he prohibited the navigation of the strait by foreigners. The Venetians refused to comply with this arbitrary mandate, and attempted to pass; but their vessel was struck by a ball from one of those enormous cannon which Mahomet had caused to be cast for the destruction of the Greek empire: the crew were beheaded, and their bodies hung out of the castle, to deter others from similar attempts. The castle was thence called Chocsecen, “the amputator of heads;” and such is the immutability of Turkish ferocity, that, with reason, it retains the name at this day.

Roumeli Hissar consists of five round towers, connected by massive embattled walls, ascending the slope of the hill. It is now useless as a fortress, but is applied to other more characteristic and equally important Turkish purposes. In the wall which fronts the Bosphorus, there is a low doorway concealed behind a large platanus: this is the postern of death. The fortress had for many years been converted into a prison, and may well bear the inscription which Dante read on the infernal portals,

“Lasciate ogni speranza, voi ch’entrate.”No prisoner is ever known to repass the gate of death; hence the Turks call their dismal fortress, the “towers of oblivion,” adopting the appellation given to them under the despotism of the Greek empire, when the castles were named “Lethé,” and for a similar reason.

During the struggles of the present sultan with the janissaries, it was his constant practice to have his opponents secretly arrested, and conveyed to this place. Every morning some Oda missed their old officers. They had been conveyed to this place after it was dark, entered the low doorway, and were seen no more. During this period, some Franks, who had taken a caïque to Buyukderé, where they were detained longer than they intended, were returning late. Boats are not permitted to pass the fortresses after sunset, and the signal-gun is fired: so they had to make their way secretly along, under cover of the shore. When arrived near the castles, they saw a large caïque advancing from Constantinople, and, to avoid detection, remained close under a rock, not far from the fatal gate. The strange boat approached, and landed just before it. Two distinguished-looking men, wrapped up in their pelisses, disembarked; they were held up by the arm on each side. One of them passed on in silence; the other sighed heavily as he approached, turned round, and seemed to cast a lingering look upon the world he was about to leave for ever. He then stooped his head, and disappeared, with his more impassive companion, under the fatal arch; the gate, groaning on its rusty hinges, closed behind them. The caïque returned immediately to Constantinople. The Franks then slipped past, and arrived without being stopped. The next morning it was known that two Binbashis, or colonels, who had great influence on their respective Odas, and strongly opposed the nizam geddite, were missing. They never re-appeared.

The navigation of the Bosphorus is the most lovely that ever invited a sail. Its length, in all its windings, is fifteen miles; and when the caïque glides down with the current, there is something exquisitely beautiful and grateful to the senses in every thing around. Nothing can exceed, in picturesque scenery, the whole coast on each side. It affords a continued succession of romantic wooded promontories, projecting into the stream, and presenting, at every winding of the strait, new and diversified objects. As you pass each headland, some placid bay opens to your view, in whose bosom a shaded village reposes. These are so numerous, that twenty-six occur from the Euxine to the Propontis; and in one line of coast there is a continuity of houses for six miles. From the centre of each village an enormous platanus generally rears its lofty head, and expands its wide extent of foliage: round its gigantic stem the houses are clustered, over which it forms a vast canopy, so that large villages are often covered with the shade of a single tree.

THE GREAT CEMETERY OF SCUTARI

T. Allom. J. C. Bentley.

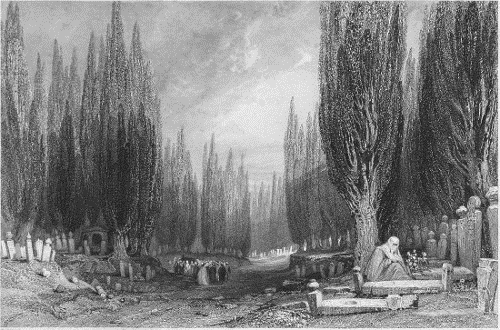

Among the first objects that present themselves to a stranger entering Turkey, are the groves of cypress extending in dark masses along the shores. These are the last resting-places of the Turks; and their sad and solemn shade, far more gloomy than any which Christian usage has adopted, informs the traveller that he is now among a grave and serious people. The Turks permit the Jews, Armenians, Greeks, and Franks to plant their cemeteries with other trees, but reserve the cypress exclusively to themselves.

The cypress has, from early ages, been a funereal tree; the ancient Greeks and Romans so considered it; and the Turks, when they entered Europe, adopted it. Its solemn shade casting a dim religious light over the tombs it covers−its aromatic resin exuding from the bark, and correcting by its powerful odour the cadaverous smell exhaled from dissolving mortality−and, above all, its evergreen and unfading foliage, exhibiting an emblem of the immortal part, when the body below has mouldered into dust and perished,−have all recommended it to the Mussulman, and made it the object of his peculiar care.

It is an Oriental practice, to plant a tree at the birth, and another at the death, of any member of a family. When one, therefore, is deposited in the earth, the surviving relatives place a cypress at the foot, while a stone marks the head of the grave; and the pious son, whose birth his father had commemorated by a platanus, is now seen carefully watering the young tree which is to preserve the undying recollection of his parent. Thus it is that the cemetery extends by constant renovation. Whether it is that the soil is naturally congenial to these trees, or that it is enriched by the use to which it is applied, it is certain the cypress attains to majesty and beauty in these cemeteries, which are seen nowhere else; their stems measuring an immense circumference, and their pointed summits seeming to pierce the clouds, exhibit them as magnificent specimens of vegetable life. Sometimes they assume a different form, and the branches, shooting out horizontally, extend a lateral shade. These varieties have been by travellers mistaken for pines, which the Turks never admit into their cemeteries.

But of all “the cities of the dead” in the Turkish empire, that of Scutari in Asia, at the mouth of the Bosphorus, is perhaps the most striking and extensive. It stretches up an inclined plain, clothing it with its dark foliage, like a vast pall thrown over the departed. It extends for more than three miles, and, like a large forest, is pierced by various avenues, leading to different places. Such is its size, that it is said the area it encloses would supply the city with corn, and the stones which mark its graves would rebuild the walls. Among the causes assigned for this increase, one is, that two persons are never buried in the same spot, so the graves are constantly expanding on every side; another, a prepossession unalterably fixed in the mind of a Turk: he considers himself a stranger and sojourner in Europe, and the Moslem of Constantinople turns his last lingering look to this Asiatic cemetery, where his remains will not be disturbed, when the Giaour regains possession of his European city; an event which he is firmly persuaded will sometime come to pass. Thus the dying Turk feels a yearning for his native soil; like Joseph in the land of Egypt, he exacts a promise from his people that “they would carry his bones hence,” and, like Jacob, says, “bury me in my grave which I have in the land of Canaan.”

Among the objects which distinguish a Turkish necropolis, is the stone placed to mark the grave. The island of Marmora, contiguous to the city, affords an inexhaustible supply of marble at a cheap rate, so that the humblest head-stones are of this valuable material. They are shaped into rude representations of the human form, surmounted by a head covered with a turban, the fashion of which indicates the rank and quality of the person: on the bust of the pillar is an Arabic inscription, containing the name of the deceased, without any enumeration of his virtues: the Turks never indulge in such panegyrics: the letters are in high relief, generally gilded with such skill, that they remain a long time as perfect and beautiful as embossed gold. The stones which designate the graves of women have no such distinction: they are marked with a lotus leaf, and surmounted with a knob like a nail, and this is said to be an intimation of the disbelief in the immortality of a female’s soul, as connected with their want of intellect.

Notwithstanding the doubt thrown upon the subject, the living female supposes that, in this life at least, she is permitted to hold communication with those who have passed to another, and render such service as may please them. In our illustration, a woman is represented enveloped in her yasmak and feridgē, performing this duty. On the grave is usually a trough or cavity, for the reception of plants or flowers, offerings of pious affection to the dead. Sometimes lattices of gilt wire form aviaries over the grave of a beloved person. Flowers and birds are among the elegant and innocent enjoyments of a Turk; and the amiable superstition of the survivor hopes to gratify her departed friend by the odour of one and the song of the other, even in his grave.

In the distance is a Turkish funeral, winding its ways through the solitude of this cypress forest. It is a group of men, for such processions are rarely attended by women, except those hired to lament the dead: as it is a belief that the body is sentient after death, and suffers torment till committed to the repose of the tomb, funerals are generally hurried, and sometimes with indecent haste: so, in this as in other things, the Turk is entirely opposed to European habits; the only hurry in which he is ever seen, is when going to his grave.

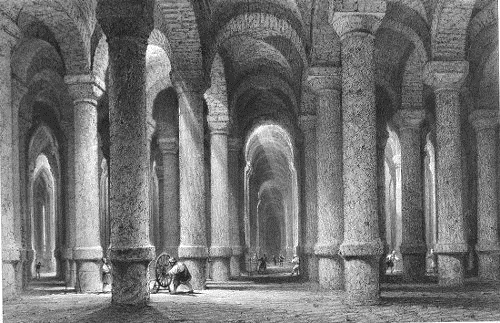

THE CISTERN OF BIN-BIR-DEREK.

CALLED, THE THOUSAND AND ONE PILLARS

T. Allom. E. Challis.

The shores of the Black Sea, among the forest-covered ramifications of the great Balkan, is a region of constant showers and copious streams, filling, naturally, small reservoirs in the mountains. Wherever such rills poured down, and became confluent, they were stopped by a mound thrown across the valley, and in this way formed into various triangular lakes at an elevation above the summit-level of the city. These reservoirs, called Hydralea, were highly prized by the Greek emperors. The embankments were faced with marble, adorned with sculpture, and dignified by the name of the sovereign who formed them. They were deemed so sacred, and of such vital importance to the city, that severe edicts were enacted to preserve them; some regulating the planting of trees, some the abstraction of water, and one exacting a penalty of an ounce of gold for every ounce of the crystal fluid. As water is more precious to the Turks than it was to the Greeks, they watch these reservoirs with even more anxiety and vigilant precaution. They call them Bendts, and have increased the number left by the Roman emperors. One of the largest and most magnificent is called Valadi Bendt, from the mother of the present sovereign, at whose expense it was erected.

From these reservoirs the water is conducted by pipes, formed of cylindrical tiles jointed together, and so conveyed to the city a distance of about fifteen miles. The ravines, that break the intervening country, are crossed by aqueducts, some of vast dimensions, striding the valleys, and towering above the forests. They are whitewashed at stated intervals, and form striking objects in distant prospects, strongly relieved by the dark woods above which they rise. One of them terminates the view up the great valley of Buyukderé, and seems, to mariners passing on the Bosphorus, like the battlements of a large city, on the distant horizon.

Besides these, there are others of more peculiar structure. They are insulated hydraulic pillars, called Souterrais, standing in long rows, like slender square castles or watch-towers. The water ascends one side of each, is received into a small square reservoir on the summit, and from thence descends the other. It climbs the next in a similar manner; and by this contrivance, for which the Turks are indebted to the Arabs, the vast expense of aqueducts is saved, and the water conveyed by many channels over various hills and valleys, in continued and never-ceasing streams, to its magnificent reservoirs in the city.

When the water arrived here, it had the same irregularity of surface to oppose, its seven hills to surmount, and seven valleys between them to cross. This was effected by a second series of aqueducts, which are described by the Byzantine historians with all the inflated language of astonishment. They are represented as “subterranean rivers” conducted through the air over the city, while the people gaze in wonder from below. Of these, but one remains to attest what they were. This is the aqueduct of Valens, stretching from hill to hill, and seen in almost every direction. Its erection was the completion of a singular prophecy: On the ramparts of Chalcedon was found a stone with an occult inscription, implying that “the walls of the city should bring water to Constantinople.” To extend these walls across the sea, seemed altogether an impossibility, and the oracular announcement was despised. But Chalcedon having incurred the resentment of the emperor, its walls were pulled down, the stones conveyed to Constantinople for building, and, among other erections formed of them, was the aqueduct of Valens, thereby accomplishing the oracle.