Полная версия

Полная версияConstantinople and the Scenery of the Seven Churches of Asia Minor

The illustration presents all the objects of interest peculiar to the place. In the foreground is a caravan crossing an antique bridge, thrown over one of the snow-dissolved currents which intersect the plain. On one side buffaloes are dragging the ponderous arrhuba; on the other, they are grazing on the low pastures, or cooling themselves in the water. The horse, in Turkey, is never degraded to a servile use: the drudgery of labour is thrown upon the buffalo. It is a singular species of ox, of immense strength, but of a structure so coarse and rude, that it seems “as if Nature’s journeymen had made it, and that not well.” Its ponderous body, its clumsy limbs, its flatted horns, and lustreless eyes, like dull glass, give it a singular appearance of obstinacy and stupidity; but it drags the greatest burdens, through places impassable to other animals, with irresistible force. On the left is the city of Brusa, with its minarets, domes, and regal tombs; and in the background are the rugged ridges of Olympus, with its snows, forests, and precipices.

EMIR SULTAN, BRUSA.

ASIA MINOR

T. Allom. W. C. Cook.

When the conqueror of Constantinople recrossed into Asia, and was preparing to attack his enemies, the sultan of Caramania, the shah of Persia, and the sultan of Egypt, who had conspired against him, he was overtaken by death near Brusa, and was brought to be buried, not in his new conquest in Europe, but in the ancient capital of his race. A magnificent mosque was erected at Emir Sultan, and his body deposited in a mausoleum beside it. This is represented in the background of the illustration. The time is that of the Ezan, when the muezzin invites the people to pray, represented by the human figures in the galleries of the minarets. When the prophet fled to Medina, he did not neglect the five periods of daily prayer: his followers wished that all the faithful should offer up theirs to Allah at the same moment, and that it should be publicly announced; but the manner of the announcement was a subject of controversy. Flags, bells, trumpets, and fires, were already used by various sects, but they were all exceptionable: the first, as not comporting with the grave sanctity of devotion−the second, as a Christian practice, and to be abhorred−the third, as a Jewish profanation−and the last, as a symbol of idolatrous worship. In this indecision they separated; but during the night one of the party had a vision of a celestial being, clothed in green, who ascended to the top of the house, and called the people to prayer. This was communicated to the Prophet, who adopted the human voice as his signal.

The houses leading to the mosque are perfect specimens of Turkish edifices. They generally have a foundation of stone to the height of eight or ten feet, and then a superstructure of wood, supported on curved beams, which rest upon the masonry. The house is covered by a far-projecting roof, which is surmounted by a kiosk, or cupola, commanding a view of the distant country. The windows are strictly closed with lattice-work of cane, in the centre of which the incarcerated female endeavours to see what is passing in the street. Whenever the clattering of hoofs and the yelping of dogs announce a passing stranger, he will perceive, if he looks up, an eye gleaming on him through the aperture, or the ruddy lips of a mouth hissing on the dogs to attack him. A Turk seldom builds a house for himself entirely of stone. The insecurity of property is such, that he never calculates on any possession, even for his own life: and he thinks, besides, it is irreligious to erect any thing like a permanent dwelling for his own use on the earth. Hence it is, that while wooden frame-work houses have long since been laid aside in Europe, a Turk, with Oriental pertinacity, still clings to them; and hence it is that fires are so frequent, and that they consume not merely houses and streets, but whole towns, and are never extinguished till the inflammable materials are exhausted.

THE VALLEY OF GUIUK-SUEY, SWEET WATERS OF ASIA

T. Allom. W. Floyd.

“Sweet Waters” is a translation of the French eaux douces, and does not imply that they are distinguished by any remarkable purity or sweetness of taste, but simply that they are not salty. Two rivulets are so named by the Franks, one in Europe and the other in Asia; and they both flow through flat alluvial soils, and are generally muddy and dirty. Their banks, however, in summer are rich and verdant, enamelled with flowers, and are places of resort, where gay and festive parties of Turks, Franks, and Rayas meet for recreation. That in Asia is the place represented in the illustration.

It is situated on the shores of the Bosphorus, near the Anadoli Hissar, or Asiatic castle, in a verdant meadow, through which the river meanders. Here the Sultan has a kiosk to which he retires in summer, to practise archery or shooting with a rifle, and amuse himself with various sports, some very coarse, where buffoonery of a very indelicate kind forms the principal part of the entertainment. This kiosk is represented in the background of the illustration. This retreat of the sultan attracts great crowds of his subjects, particularly on the evening of Friday, the Turkish sabbath. Those who resort from the European shore come in caïques; those from the Asiatic in arrhubas. This carriage, peculiar to Turkey, forms a conspicuous object in the plate. The general shape is a flooring of planks laid upon high wheels, without springs: on this are erected pillars supporting a canopy of wood, from which descend fringed curtains of silk or rich stuff. The body and canopy are sometimes highly carved and gilded: within, sit on the floor as many women as it can contain, their heads just appearing above the edge whenever the motion on the uneven road throws the curtains aside. It is drawn by two or more buffaloes, or oxen, whose tails are fastened to a long and lofty bow extending from the neck-yokes, and projecting over their backs. This arch is profusely decorated with gaudy tassels. The white locks of the animals between the horns are stained with henna, and round the necks are suspended amulets of bright blue beads, to guard them against the effects of an evil eye. It is the most improved carriage of the Turkish empire, and travels at the rate of two miles an hour. In these machines, covered up from human gaze, the sultan and great men of the empire transport their harems: they are conducted by black eunuchs, with drawn sabres, who menace any one who approaches the line of march, with instant death.

When parties proceed to those pic-nics, even the members of a family never mix together. The unsocial jealousy of a Turk so separates the sexes, that the father, husband, and brother are never seen in the same groups with their female relatives. The women assemble on one side round the fountain, and the men on the other, under the trees. Between, are the various persons who vend refreshments to both indiscriminately. On the left is the tchorbagee mixing sherbet. This word means, literally, any kind of fluid food, and it is sometimes applied to soup. A colonel of janissaries was called a tchorbagee, because he was the dispenser of soup to his corps. The drink, however, which is generally so called, is a decoction of dried fruit. Raisins, pears, peaches, prunes, and others, are prepared and kept for the purpose, and a liquor of various flavour is compounded from them, more or less acidulated or sweetened, and always cooled with ice, a small lump of which floats in every cup. On the other side is a vender of yaourt. This is a refreshment of universal consumption and extreme antiquity. The Turks affirm that Abraham was taught by an angel how to make it, and that Hagar, with her son Ishmael, would have perished in the wilderness, but for a pot of it she had the precaution to take with her. It is more certainly described by Strabo as in use in his day in the Taurica Chersonesus, and so is at least 1800 years old. It is a preparation of sour milk, forming a thick consistent mess, cool and grateful to the taste, and wholesome to the constitution. It is sold in small shallow bowls of coarse earthenware, and is the constant food of all classes in Turkey.7

The itinerant confectioner is always a necessary person at these meetings. He carries about upon his head a large wooden tray, and under his arm a stand with three legs. When required, he sets his stand, and lays his tray upon it covered with good things. The first is a composition of ground rice boiled to the consistence of a jelly, light and transparent, called mahalabie; from this lie cuts off a slice with a brass shovel, lays it on a plate, of which he has a pile on his tray, and, dividing it into square morsels, he drops on it attar of roses, or some other perfume, from a perforated silver vessel, and it forms a very cooling and delightful food. The next is halva, a composition of flour and honey, which separates into flakes; a third is a long roll like a black-pudding, formed of walnuts, enclosed in a tenacious glue, made of the inspissated juice of various fruits; the fourth is a gelatinous substance, formed into large square dies; it is made with honey and the expressed juice of fresh ripe grapes. It melts in the mouth with a very delicious flavour, and at once softens and mitigates any inflammation there. It is the most highly-prized confection of the Turks, who call it by a very appropriate name, rahat locoom, or “comfort to the throat,” which it well merits. These are the principal confections peculiar to the country; they are all excellent in their kind, and consumed in great quantities by the natives at those parties.

But of all the refreshments sought for, simple water is perhaps the most in request. It is inconceivable to a person born in a cold, humid, western climate, how necessary, not only to enjoyment but to existence, is this simple element, in the torrid regions of the East. The high estimation in which it is held, and the eagerness with which it is sought, are recorded by all writers, ancient and modern, sacred and profane. It is a pure beverage, particularly adapted to the taste of a Turk. He never rides to any distance without a leathern bottle of it attached to his saddle: he never receives a visit, that it is not handed to his guest; and in all convivial pic-nics on the grass, the sougee, or “water-vender,” is in the greatest request. He is everywhere seen moving about, with his clear glass cup in one hand, and his jar with a long spout in the other, and the cry constantly heard is, sou, soook-sou, “water, cold water.” When called, he attaches a mass of snow to the spout, and the water comes limpid and refrigerated through the pores of it. In the illustration is seen one of those magnificent fountains, by which the Turks express their respect for the precious fluid. The front is the reservoir into which the water pours. This is generally surrounded with gilded cups or basins, and a dervish, or other person, stands beside them to dispense the water.−Among the fruit sold is the grape. The Turks cultivate a peculiar kind, called chaoush; it is large, white, and sweet, and consumed in vast quantities. Though producing indifferent wine, it is perhaps the finest table-grape that is cultivated. Among the sellers of refreshments, is the oozoomgee, who weighs out his fine fruit at five paras, or less than one halfpenny, per pound.

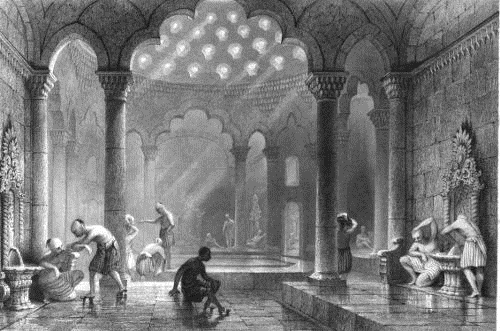

THE BATH

T. Allom. M. J. Starling.

It has been truly said of the Turks, that “they hold impurity of the body in greater detestation than impurity of the mind.” This feeling the precepts of the Koran have caused or increased. They make frequent ablution so essential, that “without it prayer will be of no value in the eyes of God.” There is no point, therefore, of religious discipline, for which the directions are so minute, or so often repeated. Two modes are prescribed. The goul, which requires the ablution of the whole body, and the hodû, which confines it to the head and arms as high as the elbow; and where water cannot be procured in the desert, the ceremony must be performed by sand or dust, as its symbol. These ablutions are enjoined to all at stated times, but besides there are occasional circumstances which render them essential. The law enumerates eleven occurrences after which the person must wash, some of which are exceedingly curious, but not fit for the public eye. So important is this practice deemed, that it forms an item in every marriage-contract. The husband engages to allow his wife bath-money, as we do pin-money; and if it be withheld, she has only to go before the cadi, and turn her slipper upside down. If the complaint be not then redressed, it is a ground of divorce.

The first objects which strike a stranger on entering a Turkish city are the mosques, and the next certain edifices, roofed like them with domes, contiguous to each other. These domes are perforated by a number of apertures, which are closed by hemispheres of glass, resembling the globes by which our streets were lighted, inverted on the roof. These edifices are the public hummums,8 or baths, and the globes the means by which the light is admitted. There is no town in the Turkish empire so obscure, or so destitute of other comforts, that is not provided with a public bath, which is open from four o’clock in the morning until eight in the evening. The bather enters a saloon, in the midst of which is a fountain, where the linen of the establishment is usually washed; round this is a divan, covered with mats or cushions, on which he sits smoking till the hummumgee, or master of the bath, directs him to undress. His clothes are carefully deposited in a shawl tied up in the corners, and remain on his seat till his return. The tellah, or bathing attendant, now approaches, with two aprons and a napkin: the first he ties round his waist, and the latter round his head. He is then led into another saloon, more heated than the first; but the heat is so regulated that he feels no difference, though divested of his clothes; and when the body is thus prepared by this gradual increase of temperature, he is led into a third, when the business of the bath commences. This, in some baths, is very fine, supported on columns, and lined with marble.

The marble flooring is so hot, that he is now obliged to mount on wooden pattens, as his bare feet could not endure to come in contact with it. A dense vapour sometimes so fills this saloon, that he sees nothing distinctly, but figures flit before him, like visions in a mist. At the sides are ornamented fountains, whence issue pipes of hot and cold water, which he mixes to his fancy, and bedews his person with it from a large copper or iron spoon provided for the purpose. Having walked or sat in this heated mist till a profuse perspiration bursts out, the tellah again approaches, and commences his operations. He lays the bather on his back or face, and pins him to the ground by kneeling heavily on him; and having thus secured him, he handles him in the rudest and most painful manner: he twists and turns the limbs, so as to seem to dislocate every joint. The sufferer feels as if the very spine was separated, and the vertebræ of the back torn asunder. It is in vain he complains of this treatment, screams out in anguish and apprehension, and struggles to extricate himself. The incubus sits grinning upon him, and torturing him till he becomes passive from very exhaustion. When this horrid operation is over, the tormentor offers to shave him; and if he make no resistance, he leaves but one small lock of hair on the crown, by which the angel of death is to draw him from his winding-sheet. It is remarkable, that while the bather is burning with heat, the flesh of this fiend, though exposed to the same temperature, is as cold and chilling as monumental marble. A second tellah now attends, and uses him more gently than the first: he envelopes his hands in gloves, or little bags of camlet, and, by a gentle and dexterous pressure of the surface, he expresses, as it were, all the deposit of insensible perspiration: it is surprising what a quantity he peels from the surface of the skin, of this inspissated fluid, resembling in colour and consistence rolls or flakes of dough.

When this substance ceases to exude, the operator rubs him with scented soap, and drenches him almost to suffocation with deluges of hot water. After this thorough ablution, he wipes him perfectly dry with soft, warm, perfumed towels, and leads him to a divan, on which he reposes some time,—still in a state of nudity, with the exception of a shawl thrown over him. Here refreshments are brought, and partaken of with an extraordinary increase of appetite; after which he rises and dresses, perfectly refreshed. Before he goes forth, a looking-glass set in mother-of-pearl is brought, to adjust his cravat, on the glass of which he deposits the price of his bath. It was originally settled at four aspers, which according to the present currency would be about one-third of a farthing, and it still continues nearly the same in the small towns and villages. In the capital, however, it is increased, in the more sumptuous baths, to fifty paras, or four pence.

Where warm-springs are found, they are immediately diverted into reservoirs, and edifices erected over them. Those of Kaplizza, near Brusa, already mentioned, are perhaps the finest in the world. In the centre saloon, under a noble dome, supported by marble pillars, is a basin of fifteen yards in circumference, also of polished marble, and five feet deep, filled with hot and limpid water. At its source, whence it first issues into day, it is at a boiling heat, and blisters the finger that incautiously feels it. In the baths, however, the heat is reduced to a tolerable temperature−in summer to 102°, and in winter to 90°. The process of bathing, substituting water for steam, is the same as that described. The salutary effects of it are highly extolled, and perhaps with reason−opening the pores, and emulging, as the hakims say, the perspiratory glands; but strangers who first submit to the rude and suffocating process, complain that it is as debilitating as it is painful, under the coarse and awkward manipulation of such an operator; and to natives who constantly use it, it is one of the enervating causes which is justly supposed to exhaust the strength and prostrate the energies of a modern Turk.

The mysteries of a female bath, it is not permitted to see, no more than those of Eleusis: all that could be known, Lady Mary Wortley Montague has told a century ago. Their bath is the great coffee-house, where they assemble, and enjoy a freedom they can nowhere else indulge. If a stranger enter this sacred place by mistake, even his mistake is punished with death. Not long since a Frank stumbled into one, supposing it to be for his own sex; he was instantly seized, and dragged before the cadi. On his way, some friendly passenger suggested to him to feign madness, as his only chance of escape: he took the hint, and did so with such success, that the cadi, instead of ordering him to execution, dismissed him with that tenderness and respect the Turks show to the foolish or insane, whom they fancy to be chosen vessels inspired by Allah with a better gift than reason. Another Frank, presuming on the impunity thus acquired, entered a female bath by design. He was seized; but not counterfeiting insanity with such success, he was suspected−and disappearing soon after, was supposed to have been strangled.

THE AURUT BAZAAR, OR SLAVE MARKET

T. Allom. P. Lightfoot.

The Aurut Bazaar, or Female Slave Market, stands in the quarter of the city near the burnt column. It consists of a quadrangular edifice, including a square area of about two hundred feet, surrounded with apartments. In the front are platforms raised four or five feet from the ground, and ascended by steps, forming a kind of colonnade, and in the rear are latticed windows. In the one, blacks and slaves of an inferior kind are kept and disposed of; in the other, those of a choicer quality, who are guarded with a more jealous vigilance, and secluded from the public eye.

All parts of the old world furnish materials for this market, but principally the shores of the Mediterranean and the eastern end of the Euxine sea. The human face is here seen in every diversity of colour, from the ebony of Nubia and Abyssinia, to the snowy whiteness of the mountains of Georgia and Mingrelia, Formerly, Franks were freely admitted into this bazaar, but they were excluded by a firman, because it was supposed they purchased slaves only for the purpose of giving them freedom; and the Turks allow no manumission unless the captives embrace Islamism, and then they become free as of right, and can be no more sold. The strictness of this exclusion, however, is now relaxed, and Franks are admitted to see, but not to purchase.

The first impression made upon a stranger is the cheerfulness and hilarity of the inmates of this prison. He enters with his mind full of the horrors of slavery: he expects to see tender females dragged from their families, the ties of nature torn asunder, and the helpless victims overwhelmed with grief−sad, and weeping, and sunk in despondency. He sees no such thing: they are singularly cheerful and gay, use every means to attract his attention, and, in their various dialects, invite him to purchase them.9 The circumstances of their early life, and the state into which they are about to enter, account for this. The condition of slavery in Turkey is generally to them an amelioriation. A regular traffic is carried on, and parents in Circassia and Georgia educate their most comely daughters, not less that they should profit by the sale, than that the children should profit by being sold. They impress upon their minds the splendid fortune that awaits them at Stambool; and when the annual traders arrive at Anaka, or other ports of the Euxine, for white slaves, the girl leaves without regret the home where she is taught to feel no ties of family affection, and embarks with a light heart and joyous anticipations of the happy prospect before her. Nor are her bright hopes disappointed: the state of slavery in which she is found, and the traffic by which she is bought, do not degrade her in the eye of the Turk who purchases her; she is transferred to the harem of some vizir or pasha, where she may become its mistress, invested with all the consequence and dignity of his favourite wife; the splendid destiny of those that are periodically purchased for the imperial seraglio is quite dazzling−any one of them may become the arbitress of empires, and the mother of sultans. Yet this bright prospect is clouded by dismal forebodings. When the reigning monarch dies, his whole female establishment purchased here, is removed to the eski seraï, or old palace, where five hundred of the most youthful and lovely females in the universe are condemned to a state of perpetual celibacy and seclusion. A still more terrible fate sometimes attends them. On vain pretexts they are sacrificed to the caprice or suspicion of the successor to the throne; and hundreds at once, in the prime of life and splendour of beauty, are consigned to a watery grave.

The merchants who purchase slaves are usually Jews. When a female of great beauty is not accomplished in the arts of pleasing, the Jew undertakes her instruction. She is taught, by competent masters, music, dancing, and other personal attractions−the cultivation of the mind is never thought of. When her value is thus enhanced by her acquirements, the most extravagant price is exacted and given. The usual purchase of a young white slave is 6000 piastres, or about £100: for a black, merely intended for the domestic drudgery which a Turkish woman will not submit to, 1200 piastres, or £16.

The illustration represents the act of sale. On one side are females purchasing black servants. A slight examination as to health and strength is all that is used. The girl starts up, draws her scanty coarse garments about her, and, with a merry laugh and cheerful countenance, trips away after her mistress. The severe decorum of a Turk at once changes her half-nakedness for a more suitable dress: her head and feet are no longer bare−her dark visage is dignified with a snow-white veil−—and she feels pride and gratification in her new and altered state. On the other side are white slaves, who are examined not by females, but by a master, of whose happiness they are hereafter to constitute a part. He is attended by his black eunuch, and the slave-merchant is pointing out all the personal charms of his purchase, and eulogising those which escape his observation. In the gallery above, are slave-merchants settling their various accounts, with the aid of coffee and tobacco.