Полная версия

Полная версияПозитивные изменения. Том 2, № 3 (2022). Positive changes. Volume 2, Issue 3 (2022)

PhD in Psychology, Leading Expert, Centre for Technological Innovations, Institute of Social and Economic Design at the Higher School of Economics

Olga Mitina

Candidate of Sciences in Psychology, Leading Researcher at the Communication Psychology Laboratory, Faculty of Psychology, Lomonosov Moscow State University

In this article, we present the results and methodology of a study conducted back in 2017. It was published in an abridged form in English, in a collection of articles on social entrepreneurship in several parts of the world[39], but has not previously been released in its entirety, describing the full methodology. We decided to take this step after discovering that our previous study of the perception of social entrepreneurs, performed on a much smaller scale and using a simplified methodology, which included only two regions (Russia and Kazakhstan), prompted a plethora of other studies following this methodology, with the possibility of comparing the regions among themselves, viewing the situation in dynamic, etc.[40]

Thus, firstly, we would like to show the possibility of applying the extended methodology in the research of the image of social entrepreneurship, based on psychosemantics. Secondly, it seems important to us to enable contemporary researchers to make retrospective comparisons, based on the past data, of changes in the current and future perceptions of social entrepreneurs in these regions. Lastly, it seems that an inquisitive researcher could use the results to predict the current situation with the development of social entrepreneurship in the CIS, which provides an opportunity to do some forecasting for the future.

The discussion related to the image of the social entrepreneur has become particularly relevant in today’s Russia due to the recent legislative enshrinement of the term “social entrepreneurship.” Currently the law does not include, for example, non-profit organizations in the definition of social enterprises (however, they are still not prohibited from selling their goods and services, e.g. in case of autonomous non-profit organizations).

Naturally, all these changes also have an impact on what remains in the minds of different audiences from different countries when they hear this mysterious phrase (which is also contradictory for some audiences) “social entrepreneurship.”

THE IMAGE OF THE SOCIAL ENTREPRENEUR AS AN OBJECT OF RESEARCHThe image of a social entrepreneur can be defined as a complex set of characteristics that includes his/her values, thinking style, specific actions, and the nature of those actions (Bruner, J. & Tagiuri, R., 1954). Unlike authority or reputation, which are formed largely at the cognitive level, the image is formed on the basis of emotional perception rather than on analysis. This perception may not even obey the laws of logic, but rather be formed at an unconscious level.

Understanding the image as a social representation (Moscovici, 1981) allows us to develop an adequate methodology for studying the formation and dynamics of its properties, which are the result of long-term influence and significant transformations. This set of characteristics is, on the one hand, very stable, but on the other hand, it is constantly reinforced and changed in the process of social interactions, adapting to the requirements of a particular situation.

The image of the social entrepreneur is a multidimensional phenomenon. We can describe it through the prism of at least two dimensions: social contribution (the ability to solve social problems) and entrepreneurial potential – financial stability of his/her enterprise, his/her professionalism as a leader, his/her competitiveness, his/her contribution to the economic development. Another possible dimension is the dependence on external resources – the need for support from the government and other sources. The next important aspect is innovation, as this is one of the most significant qualities in the vocabulary of social entrepreneurship. Does this property fit the image of the social entrepreneur in the realities of life? It is important to note that the image of a social entrepreneur should not be complicated and overloaded with different properties or parameters. It should be easy to understand, based on the prevailing views of the population.

This study aims to identify key properties of the social entrepreneur’s image in Russia, Kazakhstan and Belarus, and to determine the differences between them in each of these countries.

To conduct a comparative analysis of images, we use the psychosemantic approach. Psychosemantic methods are effective in studying people’s perceptions of an object. In particular, for recreating the framework of categories that define the public perception of social entrepreneurs. Multidimensional assessment methods developed within the framework of psychosemantics enable us to differentiate between the perception of a social entrepreneur in his/her home country and in other countries. The respondents are asked to rate the social entrepreneur’s image by key factors reflecting a range of the most important properties, such as social effect, financial stability, motivational properties, dependence on external resources, and others.

This approach has long been used in political psychology research (in particular, to describe images of political leaders, countries, gender researchers and many others). It is also actively used in ethnic psychology, social communication psychology, and arts psychology (Petrenko, Mitina & Berdnikov, 2002; Petrenko & Mitina, 2000; Petrenko, 2005).

RESEARCH METHODOLOGYExperimental psychosemantics is a relatively new field of Russian psychology. This approach uses the methodology of constructing subjective semantic spaces as operational models of categorial structures of individual and social perception and is intended to recreate the image of the world in different areas of human life. The task of psychosemantics involves reconstructing the individual system of meanings through which the subject perceives the world, other people, himself, genesis, as well as the systemic functioning of all these objects.

The experimental paradigm of psychosemantics derives from C. Osgood’s method of constructing semantic spaces (Osgood, C. E., Suci, G. J., & Tannenbaum, P. H., 1957) (semantic differential) and G. Kelly’s theory of personal constructs (repertory grid technique) (Kelly, G., 1955). It includes multidimensional statistical methods for revealing the categorial structure of the subject’s perception. Russian psychosemantics is based on the methodology employed by the schools of L. Vygotsky, A. Leontiev, A. Luria, S. Rubinstein, and is related to the problem of the formation of everyday social perception. While being a psychological discipline, psychosemantics nevertheless has a clear interdisciplinary character, connected with philosophy and sociology.

Psychosemantic approach is peculiar in that it is based on analyzing the categorial structures of the perception and the development of a system of meanings through which the subject perceives the world. The subject classifies, evaluates or scales objects observed, makes judgments about similarities and differences between objects, etc. The revealed structures inherent in the data matrix are interpreted as categorial structures of the subject’s perception. The application of multivariate statistical methods makes it possible to identify these structures and facilitates their further interpretation. For example, factor analysis makes it possible to identify “bundles” of interrelated features, constructs, and thus bring the initial basis of descriptive features down to certain generalized categories – the factors that make up the coordinate axes of the semantic space. The factor loadings of each descriptive characteristic show the degree to which a given constituent aspect is expressed in that property and how it corresponds geometrically to its projection on the factor axis. In mathematical terms, constructing a semantic space means reducing large dimensions (traits, scales, descriptors) to smaller ones, formed by categories of factors. Semantically, factor categories represent a certain meta-language that is necessary to describe meanings, so semantic spaces allow us to assign values to a fixed alphabet of factor categories, perform semantic analysis of these values, make judgments about their similarity or difference, and calculate semantic proximity between different values by calculating the distance between corresponding coordinate points in n-dimensional space.

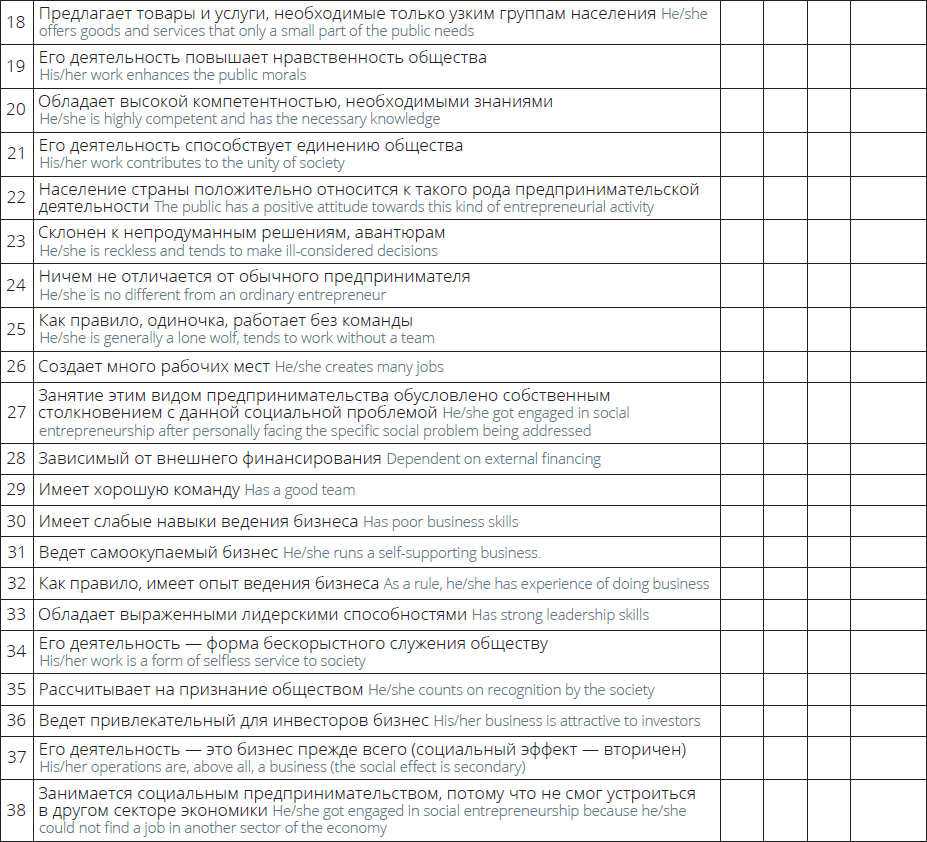

To use the psychosemantic approach to building a social entrepreneur’s image, we developed a list of 38 characteristics[41]. These characteristics were presented as statements. For example, “He/ she believes that the state must assist his/her development,” “Competitive,” “Offers an innovative solution to a social problem,” “Can hardly be called a happy person,” etc. The respondents were asked to rate each statement on a scale of 1 to 5 based on their perceived relevance of that statement to a specific object of study. The list of objects to be evaluated includes 4 items for each country:

1. “The Social Entrepreneur in his/her home country”;

2. “The Social Entrepreneur in the United States”;

3. “The Social Entrepreneur under “perfect conditions”;

4. “Social Entrepreneur in Russia” – for respondents from Kazakhstan and Belarus, and “Social Entrepreneur in Kazakhstan” – for respondents from Russia.

Participants of the SAP UP 2017 contest were chosen as the respondents for the study. Filling out the research questionnaire was part of the application process. Based on the responses, we can say that all respondents identify themselves as social entrepreneurs. The sample size was 323 respondents: 105 from Belarus, 91 from Kazakhstan, and 127 from Russia.

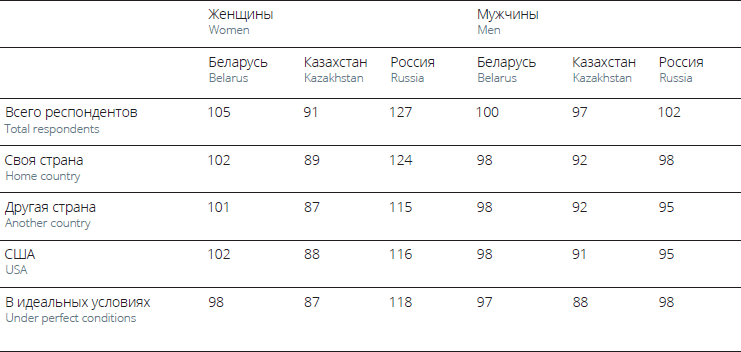

Of the total number of protocols for each country (see Table 1), we excluded those in which respondents used one response category in more than 90 % of the answers. In other words, if the respondent rated one object with 38 points and distributes the remaining 4 points among other categories, such questionnaires would be excluded from the study. Table 1 shows the number of protocols completed correctly for each sample in each country.

An exploratory factor analysis using the principal component method was used for statistical analysis of the data. Rotation method: Oblimin rotation with Kaiser normalization.

Table 1. Total sample composition and number of “correct” protocols

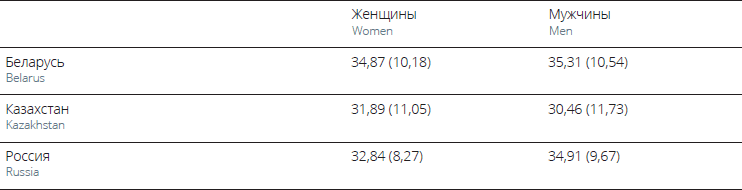

Table 2. Breakdown of respondents by age[42]

The first stage was to analyze the factor structures in the perception of the image of a social entrepreneur in his/her home country and in other countries. The analysis was conducted in each sample population.

Based on the analysis, we can distinguish four main factors in the final matrix for assessing the image of a social entrepreneur. While the descriptions of these factors have some nuances, in general respondents from Russia, Kazakhstan and Belarus highlighted the following properties (See Figure 1):

1. An effective entrepreneur creating social value, offering an innovative solution to a social problem with the support of foundations, investors, and the public;

2. Dependent on outside funding, weak business, not supported by the state and society, unhappy person;

3. More of a commercial rather than social entrepreneur, an unsuccessful businessman; a loner, working without a team;

4. Not supported by the state and the church.

This factor reflects a “healthy” model that combines significant social impact with an effective business model that is accompanied by support from foundations, investors and the public. This factor was found in the survey of all respondents. On the one hand, we can say that this is a basic, general aspect for assessing the image of a social entrepreneur.

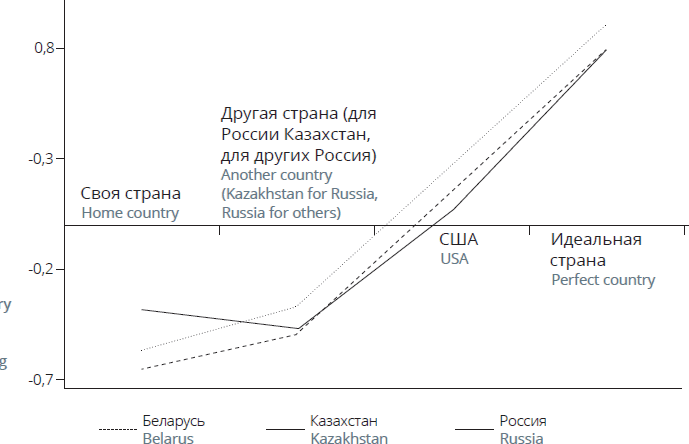

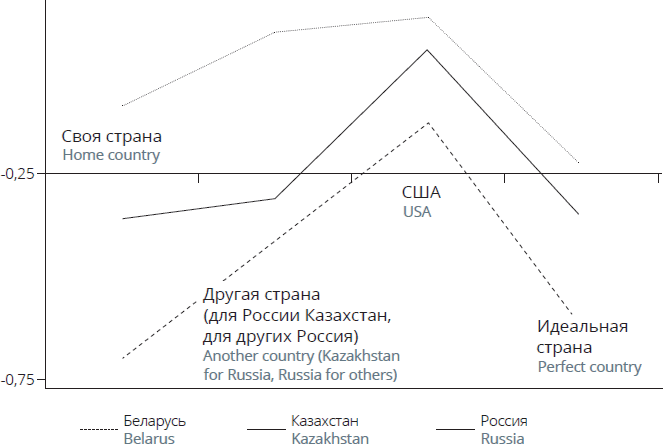

On the other hand, it is interesting to see how the respondents have ranked this property in relation to their home country and others by this criterion. As can be seen from Figure 1, only the “social entrepreneur under perfect conditions” can be used as the criterion “An effective entrepreneur creating social value, offering an innovative solution to a social problem with the support of foundations, investors, and the public.” If we talk about this criterion in relation to the characteristics of a social entrepreneur in the United States, it has been rated positively (above zero) by respondents from all three countries. Respondents from Kazakhstan give higher scores for this factor than respondents from Belarus and Russia (p = 0.091 and p = 0.007). In general, we can say that respondents assess the image of a social entrepreneur in the United States as being much closer to the “perfect” picture, than the image of their home country and the other two.

Figure 1. Evaluation of country images based on factor 1 “An effective entrepreneur creating social value, offering an innovative solution to a social problem with the support of foundations, investors, and the public.”

In evaluating their home countries by this criterion, respondents in all three countries gave negative scores (below “zero”). At the same time, the image of the social entrepreneur is characterized rather by opposing qualities. Russian respondents are more positive about the image of social entrepreneurs in their home country – they give higher ratings than respondents from Belarus and Kazakhstan to social entrepreneurs in their respective home countries (p = 0.001 and p = 0.026).

For respondents from Belarus and Kazakhstan, the characteristics of all countries differ significantly. The respondents noted minimal differences between their home countries and Russia (p = 0.062 and p = 0.018). According to respondents from Russia, there is no difference between the image of a social entrepreneur in their home country and Kazakhstan by this criterion. In general, we can say that respondents from Kazakhstan and Belarus gave much more similar answers than the respondents from Russia (See Figure 2).

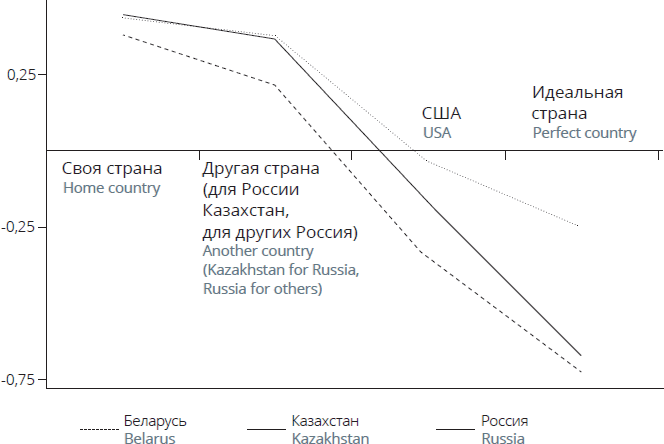

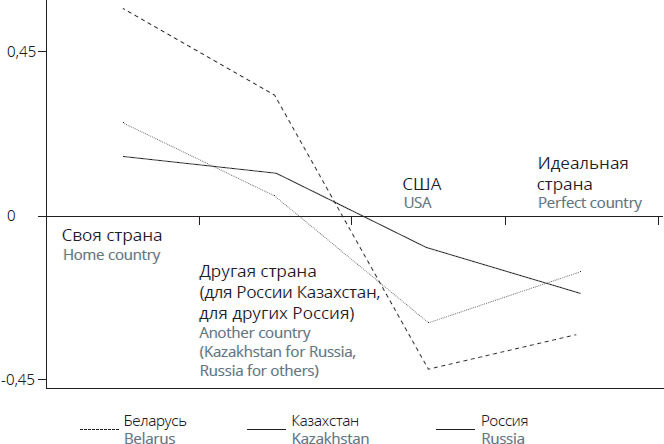

Based on Figure 2, we can see the same trend as in the analysis by criterion 1: respondents from Russia, Kazakhstan and Belarus describe the image of a social entrepreneur in the United States and “social entrepreneur under perfect conditions” more positively than in other countries (including their own). According to study participants, the image of a social entrepreneur is not so positive in their home countries. Respondents from the CIS countries attribute opposite properties to the criterion of “not dependent on external funding, running a self-sustaining business, etc.” in relation to their country. At the same time, this quality has a higher score in relation to the definition of the image of “social entrepreneur under perfect conditions,” and is less significant for the United States (but, one way or another, refers to the opposite side of the factor under consideration, because it is below zero).

Figure 2. Assessments of country images for factor 2 “Dependent on outside funding, weak business, not supported by the state and society, unhappy person.”

At the same time, respondents from Belarus are more positive about the image of a social entrepreneur in the United States (attributing the opposite characteristic to factor 2: “Dependent on outside funding, weak business, not supported by the state and society, unhappy person”) than respondents from Kazakhstan and Russia (p = 0.001 and p = 0.041). Respondents from Kazakhstan assess the image of a social entrepreneur “under perfect conditions” with the lowest score for factor 2, compared with the respondents from Belarus and Russia (p <0.001).

Another trend discovered for factor 2 is the similarity in the respondents’ assessments of the image of a social entrepreneur in their home countries and in relation to the “other country” (Russia for Belarus and Kazakhstan, and Kazakhstan for Russia). In general, we can describe these images as having no significant differences (See Figure 3).

For this factor we see opposing trends, with significant differences in the assessment of the image of a social entrepreneur in relation to their home country: p <0.001 between Belarus and Kazakhstan, p = 0.013 between Belarus and Russia, p = 0.056 between Kazakhstan and Russia.

Another interesting trend was that the respondents from all three countries rated only gave high scores in this factor to the image of a social entrepreneur from the United States. Respondents from Belarus and Russia do not attribute this property to any other country.

Figure 3. Country image scores by factor 3 “More of a commercial rather than social entrepreneur, an unsuccessful businessman; a loner, working without a team.”

The respondents from Kazakhstan demonstrate a completely different perception of this property. They attribute it to the definition of social entrepreneurs in all countries, including their own. Respondents from Kazakhstan also have a significantly different perception of the social entrepreneur in Russia compared to Belarus (p=0.001), and so do respondents from Russia when describing a social entrepreneur from Kazakhstan (p=0.005).

As for assessments of the “perfect country,” the respondents from Belarus show a substantial difference compared to the representatives of Kazakhstan (p = 0.006) and Russia (p = 0.048) (See Figure 4).

For factor 4, we can also recognize a trend common to the first two factors, that is a more positive characterization of the image of a social entrepreneur in the United States and “under perfect conditions,” compared to the characteristics that respondents applied to their home country and “other countries.” As we can see, respondents from Belarus generally do not describe social entrepreneurs in their country as supported by the state and the church. Their estimates differ significantly from those of the respondents from Russia (p <0.001) and Kazakhstan (p = 0.001). The respondents from these two countries also gave positive ratings to this factor, with a level above zero. Respondents from Belarus also attribute this characteristic to the image of a social entrepreneur in Russia, and this assessment is significantly different from the Russian (p = 0.023) and Kazakh (p = 0.005) respondents.

Figure 4. Country image scores for factor 4 “Not supported by the state and the church”

CONCLUSION

Based on our analysis of the findings, the following main conclusions can be drawn:

1. There are four main factors in assessing the image of the social entrepreneur in each of the three countries: Kazakhstan, Belarus and Russia. These factors are;

• An effective entrepreneur creating social value, offering an innovative solution to a social problem with the support of foundations, investors, and the public;

• Dependent on outside funding, weak business, not supported by the state and society, unhappy person;

• More of a commercial rather than social entrepreneur, an unsuccessful businessman; a loner, working without a team;

• Not supported by the state and the church.

2. Images of social entrepreneurs in the CIS countries – Russia, Kazakhstan and Belarus – have significantly different properties from the definition of social entrepreneurs in the United States and social entrepreneurs “under perfect conditions.” In general, the social entrepreneurs of their own and other CIS countries are described as “weaker,” that is, less effective and less innovative; they depend on external funding and are not supported by the government, the public, and the church. The respondents rated the image of a social entrepreneur in the United States as much closer to the “perfect” conditions than in each of the three countries surveyed.

3. There is a specific characteristic inherent in the image of social entrepreneurs in the United States. According to the respondents, it is “profit-oriented,” that is, their activities are more commercial than social. Conversely, study participants from Russia and Belarus believe that social entrepreneurs in their countries are more focused on social outcomes and solving social problems. Meanwhile, respondents from Kazakhstan believe that social entrepreneurs are more profit-oriented in all three countries.

4. Social entrepreneurs from Belarus mostly rate the image of a social entrepreneur in their country as “weak”. They give the lowest scores (compared to other respondents) to their country on factor 1 (“An effective entrepreneur creating social value, offering an innovative solution to a social problem with the support of foundations, investors, and the public”), and the highest for factor 4 (“Not supported by the state and the church”). But they also describe the image of a social entrepreneur in their home country as not fitting strongly with the description “More of a commercial rather than social entrepreneur, an unsuccessful businessman; a loner, working without a team” than respondents from other countries.

5. Among the CIS countries that participated in the study, Russian respondents are more positive about the image of a social entrepreneur in their country than respondents from Belarus and Kazakhstan assessing the situation in their respective home countries (this is especially evident in the analysis of factors 1 and 4).

6. In general, respondents from Russia, Belarus and Kazakhstan have similar views on the image of a social entrepreneur in relation to each of the objects: their home country, the United States and the “perfect country.” The respondents had different views (especially when evaluating their home countries) with respect to the property “More of a commercial rather than social entrepreneur, an unsuccessful businessman; a loner, working without a team.” “More social” is the image of a social entrepreneur in their home country, according to Belarusian respondents. “More commercial” is the image of a social entrepreneur in Kazakhstan, according to Kazakh respondents.

7. Social entrepreneurs from all three countries tend to attribute the characteristic “Not supported by the state and the church” to the image of a social entrepreneur in their home country and other CIS countries (Russia for Kazakhstan and Belarus, and Kazakhstan for Russia). Conversely, “Supported by the state and the church” for social entrepreneurs in the U. S. and “under perfect conditions.”

8. Social entrepreneurs from the three countries tend to attribute the property “Dependent on outside funding, weak business, not supported by the state and society, unhappy person” to the image of a social entrepreneur in their home country and other CIS countries (Russia for Kazakhstan and Belarus, and Kazakhstan for Russia). The opposite is attributed to the image of social entrepreneurs in the United States and entrepreneurs “under perfect conditions.”

APPENDIX 1. EXAMPLE OF A QUESTIONNAIRE FORMDear ______,

You are invited to participate in a public opinion survey on social entrepreneurship in different countries.

Please rate (on a scale from 0 to 5) the extent to which, in your opinion, a particular statement is typical of a social entrepreneur in each of the countries listed below. Place ‘5’ in the respective cell if the quality is expressed to the maximum extent, 0 if the opposite is expressed to the maximum extent. Use ratings 1, 2, 3, 4 to mark values in-between.

Answers are anonymous, but your opinion will describe a holistic picture of the public attitude towards social entrepreneurship in the world.

Thank you very much for your participation!

1. Mitina, O. V. & Petrenko, V. F. (2000). A Cross-Cultural Study of Stereotypes of Female Behavior (in Russia and the United States). “Voprosy Psychologii” journal, 1, p.68–86. (In Russian).