Полная версия:

Economics

The short- and medium-term impact of the formation of a common market is mainly felt through an increase in trade between member countries. TRADE CREATION is typically associated with a reallocation of resources within the market favouring least-cost supply locations and a reduction in prices resulting from the elimination of tariffs and lower production costs. (See GAINS FROM TRADE.)

In addition, a common market can be expected to promote longer-term (dynamic) changes conducive to economic efficiency through:

(a) COMPETITION. The removal of tariffs, etc., can be expected to widen the area of effective competition; high-cost producers are eliminated, while efficient and progressive suppliers are able to exploit new market opportunities;

(b) ECONOMIES OF SCALE. A larger ‘home’ market enables firms to take advantage of economies of large-scale production and distribution, thereby lowering supply costs and enhancing COMPARATIVE ADVANTAGE;

(c) TECHNOLOGICAL PROGRESSIVENESS. Wider market opportunities and exposure to greater competition can be expected to encourage firms to invest and innovate new techniques and products;

(d) INVESTMENT and ECONOMIC GROWTH. Finally, the virtuous circle of rising income per head, growing trade, increased productive efficiency and investment may be expected to combine to produce higher growth rates and real standards of living.

The EUROPEAN UNION is one example of a common market. See ANDEAN PACT.

communism a political and economic doctrine that advocates that the state should own all property and organize all the functions of PRODUCTION and EXCHANGE, including LABOUR. Karl MARX succinctly stated his idea of communism as ‘from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs’. Communism involves a CENTRALLY PLANNED ECONOMY where strategic decisions concerning production and distribution are taken by government as opposed to being determined by the PRICE SYSTEM, as in a market-based PRIVATE ENTERPRISE ECONOMY. China still organizes its economy along communist lines, but in recent years Russia and other former Soviet Union countries and various East European countries have moved away from communism to more market-based economies.

community charge see LOCAL TAX.

company see FIRM.

company formation the process of forming a JOINT-STOCK COMPANY, which involves a number of steps:

(a) the drawing up of a MEMORANDUM OF ASSOCIATION;

(b) the preparation of ARTICLES OF ASSOCIATION;

(c) application to the COMPANY REGISTRAR for a CERTIFICATE OF INCORPORATION;

(d) the issue of SHARE CAPITAL;

(e) the commencement of trading.

company laws a body of legislation providing for the regulation of JOINT-STOCK COMPANIES. British company law encouraged the development of joint-stock companies by establishing the principle of LIMITED LIABILITY and providing for the protection of SHAREHOLDERS’ interests by controlling the formation and financing of companies. The major provisions of UK company law are the 1948, 1976 and 1989 Companies Acts. See ARTICLES OF ASSOCIATION, MEMORANDUM OF ASSOCIATION, FIRM.

company registrar the officer of a JOINT-STOCK COMPANY who is responsible for maintaining an up-to-date SHARE REGISTER and for issuing new SHARE CERTIFICATES and cancelling old share certificates as shares are bought and sold on the STOCK EXCHANGE. Many companies, however, have chosen to subcontract these tasks to specialist institutions, often departments of commercial banks.

The role of the company registrar identified above should not be confused with that of the role of the government’s REGISTRAR OF COMPANIES, who is responsible for supervising all joint-stock companies.

comparability an approach to WAGE determination in which levels or increases in wages for a particular group of workers or for an industry are sought or offered through COLLECTIVE BARGAINING, which maintains a relationship to those for other occupations or industries. Comparability can lead to COST-PUSH INFLATION.

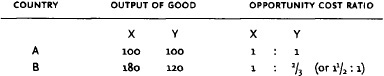

Fig. 24 Comparative advantage. The physical output of X and Y from a given factor input, and the opportunity cost of X in terms of Y. The opportunity cost of producing one more unit of X is 1Y in country A, and ⅔Y in country B. The opportunity cost of producing one more unit of Y is 1X in country A, and 1½X in country B.

comparative advantage the advantage possessed by a country engaged in INTERNATIONAL TRADE if it can produce a given good at a lower resource input cost than other countries. Also called comparative cost principle. This proposition is illustrated in Fig. 24 with respect to two countries (A and B) and two GOODS (X and Y).

The same given resource input in both countries enables them to produce either the quantity of Good X or the quantity of Good Y indicated in Fig. 24. It can be seen that Country B is absolutely more efficient than Country A since it can produce more of both goods. However, it is comparative advantage not ABSOLUTE ADVANTAGE that determines whether trade is beneficial or not. Comparative advantage arises because the marginal OPPORTUNITY COSTS of one good in terms of the other differ as between countries (see HECKSCHER-OHLIN FACTOR PROPORTIONS THEORY).

It can be seen that Country B has a comparative advantage in the production of Good X for it is able to produce it at a lower factor cost than Country A; the resource or opportunity cost of producing an additional unit of X is only ⅔ Y in Country B, whereas in Country A it is 1Y.

Country A has a comparative advantage in the production of Good Y for it is able to produce it at lower factor cost than Country B; the resource or opportunity cost of producing an additional unit of Y is only 1X, whereas in Country B it is 1½X.

Both countries, therefore, stand to increase their economic welfare if they specialize (see SPECIALIZATION) in the production of the good in which they have a comparative advantage (see GAINS FROM TRADE for an illustration of this important proposition). The extent to which each will benefit from trade will depend upon the real terms of trade at which they agree to exchange X andY.

A basic assumption of this presentation is that factor endowments, and hence comparative advantages, are ‘fixed’. Dynamically, however, comparative advantage may well change. It may do so in response to a number of influences, including:

(a) the initiation by a country’s government of structural programmes leading to resource redeployment. For example, a country that seemingly has a comparative advantage in the supply of primary products such as cotton and wheat may nevertheless abandon or de-emphasize it in favour of a drive towards industrialization and the establishment of comparative advantage in higher value-added manufactured goods;

(b) international capital movements and technology transfer, and relocation of production by MULTINATIONAL COMPANIES. For example, Malaysia developed a comparative advantage in the production of natural rubber only after UK entrepreneurs established and invested in rubber-tree plantations there. See COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGE (OF COUNTRIES).

comparative cost principle see COMPARATIVE ADVANTAGE.

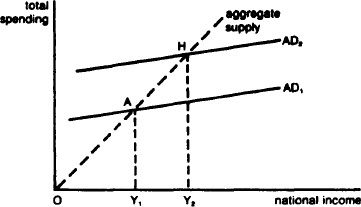

comparative static equilibrium analysis a method of economic analysis that compares the differences between two or more equilibrium states that result from changes in EXOGENOUS VARIABLES. Consider, for example, the effect of a change in export demand on the EQUILIBRIUM LEVEL OF NATIONAL INCOME as shown in Fig. 25. Assume that foreigners demand more of the country’s products. Exports rise and the aggregate demand schedule shifts upwards to a new level (AD2), resulting in the establishment of a new equilibrium level of national income Y2 (at point H). The effect of the increase in exports can then be measured by comparing the original level of national income with that of the new level of national income. See DYNAMIC ANALYSIS, EQUILIBRIUM MARKET PRICE (CHANGES IN).

compensation principle see WELFARE ECONOMICS.

competition 1 a form of MARKET STRUCTURE in which the number of firms supplying the market is used to indicate the type of market it is, e.g. PERFECT COMPETITION (many small competitors), OLIGOPOLY (a few large competitors). 2 a process whereby firms strive against each other to secure customers for their products, i.e. the active rivalry of firms for customers, using price variations, PRODUCT DIFFERENTIATION strategies, etc. From a wider public interest angle, the nature and strength of competition has an important effect on MARKET PERFORMANCE and hence is of particular relevance to the application of COMPETITION POLICY. See COMPETITION METHODS, MONOPOLISTIC COMPETITION, MONOPOLY.

Fig. 25 Comparative static equilibrium analysis. The initial level of national income is Y1 (at point A) where the AGGREGATE DEMAND SCHEDULE (AD1) intersects the AGGREGATE SUPPLY SCHEDULE (AS).

Competition Act 1980 a UK Act that extended UK COMPETITION LAW by giving the OFFICE OF FAIR TRADING (OFT) wider powers to deal with restraints on competition such as EXCLUSIVE DEALING, TIE-IN SALES, etc. Previously, these practices could be dealt with only in the context of a full-scale and lengthy monopoly probe, whereas the Act now allows the OFT to deal with them on a separate one-off basis. See COMPETITION POLICY (UK).

Competition Act 1998 a UK Act that consolidated existing competition laws but also contained new prohibitions, powers of investigation and penalties for infringements of the Act. The Act is designed to bring UK competition law into line with European Union competition law as currently enshrined in Articles 85 and 86 of the Treaty of Rome.

The Act covers two key areas of competition policy: anti-competitive agreements and market dominance.

(a) The Act prohibits outright agreements between firms (i.e. COLLUSION) and CONCERTED PRACTICES that prevent, restrict or distort competition within the UK (the Chapter 1 prohibition). This prohibition applies to both formal and informal agreements, whether oral or in writing, and covers agreements that contain provisions to jointly fix prices and terms and conditions of sale; to limit or control production, markets, technical development or investment; and to share markets or supply sources.

(b) The Act prohibits the ‘abuse’ of a ‘dominant position’ within the UK (the Chapter 2 prohibition). The Act specifies dominance as a situation where a supplier ‘can act independently of its competitors and customers’. As a general rule, a dominant position is defined as one where a supplier possesses a market share of 40% or above. Examples of ‘abuse’ of a dominant position specified in the Act include charging ‘excessive’ prices, imposing restrictive terms and conditions of sale to the prejudice of consumers and limiting production, markets and technical development to the prejudice of consumers.

The Act established a new regulatory authority, the COMPETITION COMMISSION, that took over the responsibilities previously undertaken by the Monopolies and Mergers Commission and the Restrictive Practices Court. Under the Act, the OFFICE OF FAIR TRADING (OFT) has the power to refer dominant firm cases and cases of suspected illegal collusion to the Competition Commission for investigation and report.

The Act gives the OFT wide-ranging powers to uncover malpractices. For example, if there are reasonable grounds for suspecting that firms are operating an illegal agreement, OFT officials can mount a ‘dawn raid’ – ‘entering business premises, using reasonable force where necessary, and search for incriminating documents’. The Act also introduces stiff new financial penalties. Firms found to have infringed either prohibitions may be liable to a financial penalty of up to 10% of their annual turnover in the UK (up to a maximum of three years). See COMPETITION POLICY, COMPETITION POLICY (UK), COMPETITION POLICY (EU), ANTICOMPETITIVE AGREEMENT, RESTRICTIVE TRADE AGREEMENT.

Competition Appeals Tribunal (CAT) a body established by the ENTERPRISE ACT 2002 to hear appeals in regard to ‘disputed’ merger cases. The OFFICE OF FAIR TRADING has the power to refer proposed mergers and takeovers to the COMPETITION COMMISSION for investigation if it believes that the merger/takeover would ‘substantially lessen competition’. If, in the OFT’s view, this is not the case, it can allow the merger/takeover to go ahead without reference. This is where the CAT comes in. An interested party (e.g. a competitor of the companies involved in the merger) may ‘appeal’ to the CAT that the OFT decision not to refer is ‘wrong’. The task of the CAT is to arbitrate and decide if there is indeed a case for reference and can ‘order’ a reference to the Competition Commission if it sees fit.

Competition Commission (CC) a regulatory body established by the COMPETITION ACT 1998 that was originally set up in 1948 as the Monopolies Commission (1948–65), then the Monopolies and Mergers Commission (1965–98) and that is responsible for the implementation of UK COMPETITION POLICY. The basic task of the Commission is to investigate and report on cases of MONOPOLY/MARKET DOMINANCE, MERGER/TAKEOVER and ANTI-COMPETITIVE PRACTICES referred to it by the OFFICE OF FAIR TRADING (OFT) to determine whether or not they unduly remove or restrict competition, thus producing harmful economic effects (i.e. economic results that operate against the ‘public interest’). The Commission is also required by the OFT to investigate cases of ‘illegal’ collusion between suppliers, i.e. cases where the OFT has good reason to suspect that an ANTICOMPETITIVE AGREEMENT/RESTRICTIVE TRADE AGREEMENT prohibited by the Competition Act 1998 is continuing to be operated ‘in secret’. (This task was formerly undertaken by the RESTRICTIVE PRACTICES COURT.)

Under UK COMPETITION LAW, monopoly/market dominance is defined as a situation where at least 40% of a reference good or service is supplied by one firm or a number of suppliers who restrict competition between themselves (CONCERTED PRACTICE or COMPLEX MONOPOLY situation). Mergers and takeovers fall within the scope of the legislation where the market share of the combined business exceeds 25% of the reference good or service or where the value of assets being merged or taken over exceeds £70 million. Anti-competitive practices are those that distort, restrict or eliminate competition in a market.

Cases referred to the Competition Commission are evaluated nowadays primarily in terms of whether or not the actions of suppliers (MARKET CONDUCT) or changes in the structure of the market (MARKET STRUCTURE) are detrimental to the potency of competition in the market and hence prejudicial to the interests of consumers and other suppliers (the so-called ‘public interest’ criterion found in earlier legislation). In cases of monopoly/market dominance, the Commission scrutinizes the actions of dominant firms for evidence of the ‘abuse’ of market power and invariably condemns predatory pricing policies that result in excessive profits. Practices such as EXCLUSIVE DEALING, AGGREGATED REBATES, TIE-IN SALES and FULL-LINE FORCING, whose main effect is to restrict competition, have been invariably condemned by the Commission, especially when used by a dominant firm to erect BARRIERS TO ENTRY and to undermine the market positions of smaller rivals. A merger or takeover involving the leading firms who already possess large market shares is likely to be considered detrimental. (See MARKET CONCENTRATION.)

In all cases, the Commission has powers only of recommendation. It can recommend, for example, price cuts to remove monopoly profits, the discontinuance of offending practices and the prohibition of anti-competitive mergers, but it is up to the Office of Fair Trading to implement the recommendations, or not, as it sees fit.

competition law a body of legislation providing for the control of monopolies/market dominance, mergers and takeovers, anti-competitive agreements/restrictive trade agreements and anti-competitive practices. UK legislation aimed at controlling ‘abusive’ MARKET CONDUCT by monopolistic firms and firms acting in COLLUSION was first introduced in 1948 (The Monopolies and Restrictive Practices (Inquiry and Control) Act), while powers to control undesirable changes in MARKET STRUCTURE were added in 1965 (The Monopolies and Mergers Act). Other notable legislation concerning the control of collusion were the Restrictive Trade Practice Acts of 1956, 1968 and 1976.

Current competition law in the UK is contained in a number of Acts:

FAIR TRADING ACT 1973

(applying to mergers and takeovers)

COMPETITION ACT 1980

(applying to anti-competitive practices)

COMPETITION ACT 1998

(applying to monopolies/market dominance and anti-competitive agreements/restrictive trade agreements)

RESALE PRICES ACTS 1964, 1976

(applying to resale price maintenance)

ENTERPRISE ACT 2002

(applying to mergers/takeovers and anti-competitive agreements)

These laws are currently administered by the OFFICE OF FAIR TRADING and the COMPETITION COMMISSION (formerly the MONOPOLIES AND MERGERS COMMISSION). See also RESTRICTIVE PRACTICES COURT.

In the EUROPEAN UNION, competition law is enshrined in Articles 85 and 86 of the Treaty of Rome (1958) and the 1980 Merger Regulation. These laws are administered by the European Com-mission’s Competition Directorate. See COMPETITION POLICY, COMPETITION POLICY (UK), COMPETITION POLICY (EU), COMPLEX MONOPOLY.

competition methods an element of MARKET CONDUCT that denotes the ways in which firms in a MARKET compete against each other. There are various ways in which firms can compete against each other:

(a) PRICE. Sellers may attempt to secure buyer support by putting their product on offer at a lower price than that of rivals. They must bear in mind, however, that rivals may simply lower their prices also, with the result that all firms finish up with lower profits;

(b) non-price competition, including:

(i) physical PRODUCT DIFFERENTIATION. Sellers may attempt to differentiate technically similar products by altering their quality and design, and by improving their performance. All these efforts are intended to secure buyer allegiance by causing buyers to regard these products as in some way ‘better’ than competitive offerings.

(ii) product differentiation via selling techniques. Competition in selling efforts includes media ADVERTISING, general SALES PROMOTION (free trial offers, money-off coupons), personal sales promotion (representatives) and the creation of distribution outlets. These activities are directed at stimulating demand by emphasizing real and imaginary product attributes relative to competitors.

(iii) New BRAND competition. Given dynamic change (advances in technology, changes in consumer tastes), a firm’s existing products stand to become obsolete. A supplier is thus obliged to introduce new brands or to redesign existing ones to remain competitive;

(c) low-cost production as a means of competition. Although cost-effectiveness is not a direct means of competition, it is an essential way to strengthen the market position of a supplier. The ability to reduce costs opens up the possibility of (unmatched) price cuts or allows firms to devote greater financial resources to differentiation activity. See also MONOPOLISTIC COMPETITION, OLIGOPOLY, MARKETING MIX, PRODUCT-CHARACTERISTICS MODEL, PRODUCT LIFE-CYCLE.

competition policy a policy concerned with promoting the efficient use of economic resources and protecting the interests of consumers. The objective of competition policy is to secure an optimal MARKET PERFORMANCE: specifically, least-cost supply, ‘fair’ prices and profit levels, technological advance and product improvement. Competition policy covers a number of areas, including the monopolization of a market by a single supplier (MARKET DOMINANCE), the creation of monopoly positions by MERGERS and TAKEOVERS, COLLUSION between sellers and ANTI-COMPETITIVE PRACTICES.

Competition policy is implemented mainly through the control of MARKET STRUCTURE and MARKET CONDUCT but also, on occasions, through the direct control of market performance itself (by, for example, the stipulation of maximum levels of profit).

There are two basic approaches to the control of market structure and conduct: the nondiscretionary approach and the discretionary approach. The non-discretionary approach lays down ‘acceptable’ standards of structure and conduct and prohibits outright any transgression of these standards. Typi-cal ingredients of this latter approach include:

(a) the stipulation of maximum permitted market share limits (say, no more than 20% of the market) in order to limit the degree of SELLER CONCENTRATION and prevent the emergence of a monopoly supplier. Thus, for example, under this ruling any proposed merger or takeover that would take the combined group’s market share above the permitted limit would be automatically prohibited;

(b) the outright prohibition of all forms of ‘shared monopoly’ (ANTI-COMPETITIVE AGREEMENT/RESTRICTIVE TRADE AGREEMENTS, CARTELS) involving price fixing, market sharing, etc;

(c) the outright prohibition of specific practices designed to reduce or eliminate competition, for example, EXCLUSIVE DEALING, REFUSAL TO SUPPLY, etc.

Thus, the nondiscretionary approach attempts to preserve conditions of WORKABLE COMPETITION by a direct attack on the possession and exercise of monopoly power as such.

By contrast, the discretionary approach takes a more pragmatic line, recognizing that often high levels of seller concentration and certain agreements between firms may serve to improve economic efficiency rather than impair it. It is the essence of the discretionary approach that each situation be judged on its own merits rather than be automatically condemned. Thus, under the discretionary approach, mergers, restrictive agreements and specific practices of the kind noted above are evaluated in terms of their possible benefits and detriments. If, on balance, they would appear to be detrimental, then, and only then, are they prohibited.

The USA by and large operates the nondiscretionary approach; the UK has a history of preferring the discretionary approach, while the European Union combines elements of both approaches. See COMPETITION POLICY (UK), COMPETITION POLICY (EU), PUBLIC INTEREST, WILLIAMSON TRADE-OFF MODEL, OFFICE OF FAIR TRADING, COMPETITION COMMISSION, RESTRICTIVE PRACTICES COURT, HORIZONTAL INTEGRATION, VERTICAL INTEGRATION, DIVERSIFICATION, CONCENTRATION MEASURES.

competition policy (EU) covers three main areas of application under European Union’s COMPETITION LAWS:

(a) CARTELS. Articles 85(1) and (2) of the Treaty of Rome prohibit cartel agreements and ‘CONCERTED PRACTICES’ (i.e. formal and informal collusion) between firms, involving price-fixing, limitations on production, technical developments and investment, and market sharing, whose effect is to restrict competition and trade within the European Union (EU). Certain other agreements (for example, those providing for joint technical research and specialization of production) may be exempted from the general prohibition contained in Articles 85(1) and (2), provided they do not restrict inter-state competition and trade;

(b) MONOPOLIES/MARKET DOMINANCE. Article 86 of the Treaty of Rome prohibits the abuse of a dominant position in the supply of a particular product if this serves to restrict competition and trade within the EU. What constitutes ‘abusive’ behaviour is similar to the criteria applied in the UK, namely, actions that are unfair or unreasonable towards customers (e.g. PRICE DISCRIMINATION between EU markets), retailers (e.g. REFUSAL TO SUPPLY) and other suppliers (e.g. selective price cuts to eliminate competitors). Firms found guilty by the European Commission of illegal cartelization and the abuse of a dominant position can be fined up to 10% of their annual sales turnover;