Полная версия:

The Isles of Scilly

On the granite carns where the thin soils become desiccated in summer are areas of typical plant communies (see Appendix) which include plants such as common bird’s-foot Ornithopus perpusillus, bird’s-foot-trefoil Lotus corniculatus, English stonecrop, buck’s-horn plantain, some of the tiny grasses such as silver hair-grass Aira caryophyllea and in a few places the rare orange bird’s-foot. Nearby, heathers, grasses and taller plants grow where there are deeper soils, and in some years the tiny orchid, autumn lady’s-tresses, also appears here. Where moisture is retained over the granite platform there may be one or two discrete patches of small adder’s-tongue fern.

Shipman Head Down in the north of the island is an extensive area of ‘waved heath’, the wind-eroded heath that is one of the most important habitats in the Isles of Scilly. The dominant species are ling, bell heather and western gorse, with common gorse forming dense scrub along the southeast edge and extending down towards the coast. This is where spring squill can be found on top of the plateau, as well as several species of rare lichens. Getting to Shipman Head itself can only be accomplished by a scramble down steep rocks. The promontory is accessible for a short time at low water across the very deep cleft that separates the Head from the main bulk of the island. Colonies of seabirds are able to breed on Shipman Head in relative isolation.

One curious little gem of social history that has revolutionised visiting Bryher was the building of what the islanders humorously call ‘Annekey’ or Anneka’s Quay. This is a pontoon landing on the beach just north of the old stone quay, built during 1990 as part of one of Anneka Rice’s TV programmes, Challenge Anneka. This new landing enables boats to get in to Bryher when the tide is too low to land elsewhere. The only alternative in the past was to run the boat up the beach and land passengers by a plank from the bow.

TRESCO

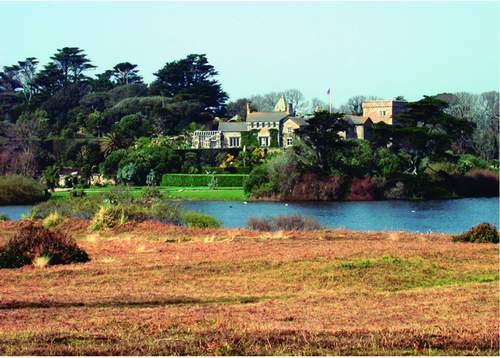

Tresco and Bryher face each other across the narrow channel that forms the sheltered anchorage of New Grimsby Harbour. Tresco is the second largest and arguably the best known of the Isles of Scilly, on account of the famed Abbey Gardens. The island is just over 3km long and 1.7km wide, and covers approximately 298 hectares. At the north end is one of the most extensive areas of waved heath in the islands, on a plateau some 30 metres high. Across the middle of Tresco, almost dividing the island in two, is the long, water-filled gash that is the Great Pool, with the Abbey Pool slightly to the south. North of Great Pool is a broad band of farmland that stretches to Old Grimsby on the east coast (Fig. 40). South of Great Pool are the Abbey Gardens and woodland around Tresco Abbey. Beyond the Gardens and on the eastern side of the island are extensive sand dunes and stretches of dune heathland. Other than rocky Gimble Porth, and the northern fringes of the island, the coastline of Tresco is mainly composed of dunes and sandy beaches.

General impressions of Tresco tend to be coloured by the presence of the Abbey Gardens and the farm, and especially the very large area of planted woodland that dominates the landscape. The island has a much more managed atmosphere than the other off-islands. This may be partly due to its history, but is mainly because almost the whole island is under one tenancy and has been mostly managed as one estate for a very long time. The present incumbent of Tresco, Robert Dorrien-Smith, took on the estate in 1973.

Even before the visitor reaches the Gardens their influence and that of the tenure of Augustus Smith and the Dorrien-Smith family is evident everywhere on Tresco. Apart from the gardens themselves, this influence is most evident in the sand dunes around Appletree Banks and Pentle Bay, where a hotch-potch of exotic plants have become established among the native dune species. Throughout the dunes are clumps of rhodostachys, the very similar Tresco rhodostachys Ochagavia carnea, bugle lily Watsonia borbonica, Agapanthus praecox

FIG 40. Old Grimsby Harbour, on the east coast of Tresco, June 2002. (Rosemary Parslow)

and red-hot pokers Kniphofia sp. growing among the marram, with balm-leaved figwort, Babington’s leek and sand sedge Carex arenaria. Where the dune has become flattened and consolidated, dune grassland and heathland have formed. Rushy Bank, just beside the road from the landing at Carn Near quay, is particularly interesting, with many unusual plants: orange bird’s-foot (found some years growing all along the edge of the concrete road) and small adder’s-tongue fern can be found here, and on the heathers nearby are rich growths of lichens, including some of the lungworts. Also beside the road at Carn Near there are banks of the extraordinary wireplant moulding itself over the other vegetation in a parody of topiary. Below the dunes, at the back of the beach, is one of the very few places where a few plants of the rare shore dock Rumex rupestris grow among the masses of the coastal form of curled dock Rumex crispus var. littoreus (see Chapter 9). As this section of coast is actively eroding, the future of this shore dock site is probably limited.

Tresco has its own heliport, opened in 1983 (Fig. 41). The island has a hotel, the first to be established on an off-island, and an established time-share business. With the draw of the Gardens, Tresco attracts more visitors than any of the islands other than St Mary’s. The heliport is on a beautiful mown stretch of grassland just beside the Gardens and is well worth looking at (but not when

FIG 41. Tresco, looking north from Oliver’s Battery across coastal dunes, the heliport and plantations, April 2005. (Rosemary Parslow)

helicopters are landing!). Like the airfield on St Mary’s it frequently attracts feeding waders and other birds. In autumn it can be one of the places to look for rare pipits and larks.

Towards the edge of the Abbey Pool (Fig. 42) the grassland is seasonally waterlogged so a band of marsh pennywort, lesser spearwort and other wetland plants extends all round the edge, and similarly around the south side of the Great Pool. When Borlase visited Tresco in 1756 he commented on ‘a most beautiful piece of fresh water edged round with Camomel Turf, on which neither Brier, Thistle, nor Flag appears. I judged it to be half a mile long, and a furlong wide.’ The chamomile turf is still there but no longer so extensive. The fine silt drawdown zone (much enriched by droppings from gulls and waterfowl) around the edge of the Abbey Pool supports a variable array of tiny wetland plants, depending on how much mud is exposed. During periods of drought some of the submerged aquatic plants become visible as the water level drops, and those growing on the mud spread quickly; six-stamened waterwort Elatine hexandra, for example, on these occasions can turn the surface of the mud bright red. Abbey Pool has a resident population of wild and domestic waterfowl, but like anywhere in Scilly it has seen some notable rarities at times.

Great Pool is much more extensive. The lake stretches right across the middle of the island, virtually dividing it in two. Surrounding Great Pool are reedbeds, areas of willow carr and some stretches of muddy foreshore. A painting of the lake and the surroundings by Augustus Smith’s sister Mrs Frances Le Marchant, executed in September 1868, shows the lake to be much more open than now, with the reedbeds only marginal (in King, 1985). The lake attracts many waterbirds, both migrants and the resident species, including gadwall, mallard and moorhen, and is an important feeding area for migrating waders. Among the reeds and in open patches along the foreshore are many common wetland plants, lesser spearwort, royal fern, bulrush (reedmace) Typha latifolia and yellow iris. The rattling songs of reed Acrocephalus scirpaceus and sedge warbler A. schoenobaenus can be heard from the reedbeds around the lake during summer. Good views across the lake can be obtained from the bird hides that are approached by boardwalks from the track north of the pool. One hide was erected in memory of the late David Hunt, the ‘Scilly Birdman’, who was resident on Tresco before moving to St Mary’s (see Chapter 4).

Much of Tresco is under agriculture, with pasture and arable fields (Fig. 43). The Tresco Estate currently runs a large herd of beef cattle. There is more tree cover generally, so that in autumn the island attracts rare migrant birds from

FIG 42. Tresco Abbey and Abbey Pool, April 2005. (Rosemary Parslow)

FIG 43. Arable fields and pine shelterbelt on Tresco. (Rosemary Parslow)

North America and elsewhere to tease the ‘twitchers’ who also flock to the islands.

Across the north end of the island is Castle Down, one of the largest areas of wind-eroded waved heath in the islands. This is a fascinating place, a plateau covered in low heather only about ankle height where the plants form long ridges as they are rolled over by the wind, with large patches of exposed bare ground between the waves. This type of heathland is not particularly species-rich but very atmospheric when the heathers are in flower and the whole place is full of the hum of bees. Besides bell heather and ling, there are several common species of grass, patches of English stonecrop, lousewort and bird’s-foot-trefoil, and lichens and mosses. The tread of many feet on the pathways across the Down, exacerbated by the eroding effect of wind and rain, have caused the braiding of many pathways. On some places on the paths are many shallow temporary pools with a transient wetland flora of starworts and lesser spearwort. Ruins of all that remains of King Charles’s Castle are on one of the high points at the western edge of Castle Down. Besides having a good population of ferns and sea stork’s-bill Erodium maritimum among its stones, the top of the castle makes a good vantage point for looking down into the Tresco Channel between Tresco and Bryher, and over the tower of Cromwell’s Castle on the headland below.

Gimble Porth on the eastern side of the headland is backed with low cliffs where gulls nest, and where some years there is a kittiwake Rissa tridactyla colony. Piper’s Hole is a deep cavern in the north-facing cliffs that can be approached by scrambling down the cliff, but a boat is needed to explore properly. It was very popular with holiday visitors in the past, and there are still postcards on sale showing it lit up with lanterns in the early 1900s. The cave consists of a long boulder-filled passage over 20m long leading to a large underground pool that can be traversed by boat (a punt used to be kept there in the past) to reach the inner chamber, which is over 40m deep. The cave system was investigated in 1993 by Philip and Myrtle Ashmole and specimens of the cavernicolous fauna collected, including a springtail new to Britain, Onychiurus argus, a troglophile species otherwise known from caves in Spain, France and Belgium (Ashmole & Ashmole, 1995).

The plantations and windbreaks originally planted by Augustus Smith and his successors are now coming to the end of their life. Much planting and felling has taken place to remove and replace the fallen timber. The woodlands are a mixture of planted trees and shrubs, escapees from the Gardens, as well as wild plants and ferns – a botanical recorder’s headache. Protected by the plantations are the ‘subtropical’ Abbey Gardens (Fig. 44). These are densely planted with a

FIG 44. Tresco Abbey Gardens, April 2005. (Rosemary Parslow)

great range of plants from countries with a Mediterranean climate, Australasia, the Canary Islands, South Africa and parts of South America (see Chapter 13). Visitors to the Abbey Gardens will also remark on the extraordinarily tame birds. In 2004 the entrance to the Gardens was updated and the tea room moved. If you visit the tea garden, kamikaze robins Erithacus rubecula snatch crumbs from your lips and blackbirds, chaffinches Fringilla coelebs and other birds will help themselves to cake from your plate. At certain times of the year the odd appearance of the house sparrows Passer domesticus, starlings Sturnus vulgaris and blackbirds – with bright yellow caps of pollen from drinking the nectar of Puya chilensis plants – has occasionally led to them being identified as something far more exotic! Another curious phenomenon in the former tea garden was the pecking of holes in the mortar of a wall by dozens of house sparrows, presumably seeking minerals after the manner of some tropical parrots.

Some of the exotic plants that grow around Tresco and the other islands are spread intentionally when people take cuttings or seeds to cultivate for their own gardens or pass around to their friends. Other plants escape from the Gardens by natural means, blown by the wind or otherwise carried accidentally, to end up elsewhere in the islands. Many of these are now established as part of the Scillonian flora. Perhaps the most unusual inhabitants of the Gardens are the two species of New Zealand stick insects that have been part of the fauna for about a century and are now found elsewhere around Tresco. Recently they have also reached St Mary’s. Also from New Zealand but less obvious are the woodland hoppers Arcitalitrus dorrieni, the little back amphipods that now live under every rock and log on the island. These are the most obvious and well-known examples, but there are many other insects and other invertebrate species that originally arrived as stowaways with horticultural material from abroad.

It is not just insects and other animals that have arrived in Scilly with introduced plants. A series of discoveries of rare introduced bryophytes began in 1961 when Miss R. J. Murphy discovered two unexpected liverworts on Tresco, Lophocolea semiteres, new to the northern hemisphere, and a new species of Telaranea that was named T. murphyae after her by Mrs Paton in 1965. Telaranea murphyae may have been introduced to Tresco from the southern hemisphere, as has happened with many other species such as Lophocolea semiteres and L. bispinosa, which are found only on Scilly and in Scotland, pointing to introduction with exotic plants. Besides Lophocolea bispinosa, found by Mrs Paton in 1967, was a moss Calyptrochaeta apiculata, later also found in East Sussex.

Since then, the moss Sematophyllum substrumulosum was first recorded as new to Britain on several of the islands (it has since been discovered to have been found, but not identified, in West Sussex in 1964). It was growing on the bark of Monterey pine in 1995 and again may have arrived with horticultural material (Paton & Holyoak, 2005). Other species recorded have included two mosses rare in Britain (Chenia leptophylla, Didymodon australasiae) and another that has become very widespread and common (Campylopus introflexus). By 2003 some of the alien bryophytes had greatly extended their ranges since the 1960s, with both alien Lophocolea species now widespread throughout the islands, and Telaranea murphyae had spread from Tresco to St Mary’s.

ST MARTIN’S

St Martin’s is a long narrow island with a mainly west-to-east axis. It is just over 3km long by 1.5km wide and covers 238 hectares if you include White Island (15ha). First impressions of St Martin’s are of long, empty white beaches (Fig. 45), intense turquoise sea, little clusters of houses tucked into the hillside and the strangely modern-looking (it actually dates from 1683) conical red and white banded tower of the daymark on high ground on Chapel Down at the eastern end of the island.

FIG 45. The south coast of St Martin’s, looking towards Tresco at low tide with the sand flats exposed. June 2005. (Rosemary Parslow)

As on St Agnes, the individual hamlets are named, rather unoriginally, Lower, Middle and Higher Town. They are strung out along the two-kilometre concrete road from Lower Town quay in the west to Higher Town Bay and New Quay, just over halfway along the length of the island. Beyond the farmland to the east the land rises up to the heathland on Chapel Down. Heathland also extends all along the northern edge of the island; only the insert of the dune grassland of the Plains and in some places wetter areas and a small pool break the continuity. Around the higher and exposed land are rocky promontories and cliffs where seabirds nest. Looking northeast from the cliffs on a clear day you can often see the cliffs of Land’s End, 45km away.

The southern shores of St Martin’s are mainly sandy, with sand dunes and just a few stretches of low cliff. Along the back of the dunes at Higher Town Bay are small bulb fields, frequently inundated by blown sand (Fig. 46). Indeed, much of St Martin’s is composed of blown sand that has been deposited over the whole top of the island in the past. This has led to some of the most impressive arable weed populations in Scilly being found here, including unusual species not found elsewhere in the islands. The sandy soils are also found around Higher Town Bay, where the cricket field is mown maritime grassland dominated by

FIG 46. Bulb fields with rosy garlic Allium roseum, whistling jacks and great brome, St Martin’s, May 2003. (Rosemary Parslow)

chamomile and several species of clover, including both suffocated Trifolium suffocatum and subterranean clover. The cricket field is low-lying and sometimes floods completely – perhaps not ideal for the cricket, but maybe why there is a superb show of chamomile most summers. The sand-dune areas around the quay and along the track ways are also places where some rare clovers are found. Suffocated clover can be difficult to find, as blown sand often drifts over the plants and completely buries them. It also flowers early in the year so has usually dried up and disappeared by early summer. In the corner of the cricket field is a small brackish pool, sometimes covered by the pretty white and yellow buttercup flowers of brackish water-crowfoot.

The dune system along the Higher Town Bay is typical of the NVC (National Vegetation Community) SD7 semi-fixed dune, relatively species-poor but with some interesting herbs such as balm-leaved figwort and Babington’s leek. In places bracken and the evergreen shrub Pittosporum crassifolium are invading the dune. A sub-prostrate form of wild privet occurs along the edge of the track. There are species of unstable foredune habitats such as sea rocket Cakile maritima where there are breaks in the dune. In summer this is one of the best places to see ringlet butterfly Aphantopus hyperantus, a recent arrival in Scilly. At the back of Lawrence’s Bay is a low cliff with a hanging curtain of the succulent Sally-my-handsome Carpobrotus acinaciformis, with its distinctive curved leaves and carmine flowers.

There is a series of rocky headlands with exposed rocks and thin soils along the north side of St Martin’s. Wind-eroded heather and gorse heathland cover the area between Top Rock Hill and the separate group of the Rabbit Rocks. The slopes below the hill are covered with bracken and gorse communities on deeper soils and a fringe of maritime grassland towards the coast. At Round Bowl both small adder’s-tongue fern and orange bird’s-foot have been recorded, but the dune is being invaded by heath and scrub species in this area. Pernagie is a group of small bracken fields below the hill with maritime grassland and a small area of heathland at Pernagie Point. The westernmost headland on St Martin’s is Tinkler’s Hill. The top of the hill has a cover of gorse scrub surrounding a smaller area of heather. At the bottom of the hill is heathland and coastal grassland alongside Porth Seal, where small adder’s-tongue fern may be found. Porth Seal is a geological SSSI on account of the raised beach and important deposits; pollen analysis from the site demonstrated the arctic tundra nature of the Devensian environment. Chaffweed Anagallis minima grows along some wet cart ruts across the heathland, but is easily overlooked. Turfy Hill may have got its name from the practice of cutting turf there formerly. Now the area is dominated by bracken communities, with smaller patches of heather and gorse. Small adder’s-tongue fern also occurs in this area, and one of the large species of New Zealand flax, Phormium colensoi, is well established and spreading.

Burnt Hill is the small promontory of open land on the north of the island between Turfy Hill and Chapel Down. It consists of mainly heather-dominated maritime heath and grassland. Inland from the promontory the heathland becomes dominated by bracken communities and a large area of gorse. Many areas of gorse and bracken are being managed to encourage the re-establishment of heathland plants. Chapel Down, where the land rises up towards the daymark, is dominated by waved heathland with scattered granite boulders and exposed granite platform very prominent towards the east. Many of the rare heathland plants, including small adder’s-tongue fern, orange bird’s-foot and chaffweed, are also found here, and this is also the territory of the St Martin’s ant Formica rufibarbis (see Chapter 14). There are steep cliffs around the edge of the headland with colonies of nesting seabirds during the summer. Above the cliffs are areas of bracken communities and gorse scrub. At Coldwind Pit near the coast there are a number of unusual aquatic plants growing in and around the pool.

On the north side of St Martin’s is an unusual open area called the Plains (Fig. 47). Formerly open grassland and low heath that had developed from dune grassland, it is becoming overgrown by gorse and scrub. Formerly small adder’s-tongue

FIG 47. North coast of St Martin’s, with the Plains and Round Island lighthouse in the distance. (Rosemary Parslow)

FIG 48. Mouse-ear hawkweed is one of the unusual species found in dune grassland on the Plains, St Martin’s. (Alma Hathway)

fern was widely distributed throughout the Plains until it became submerged by taller vegetation. Rare plants such as orange bird’s-foot and a patch of mouse-ear hawkweed Hieracium pilosella at its only known station in Scilly can be found here still (Fig. 48). Above the Plains among the dense thickets of common gorse it is also possible to find the strange pink nets of the parasitic heath dodder Cuscuta epithymum, another plant apparently only found in this one place in Scilly. The headlands and slopes along the northern side of St Martin’s also have spreading, triffid-like, populations of New Zealand flax, although control measures to reduce their numbers started in 2005. It is likely similar measures will be taken against another invasive alien, Myrtus luma, a myrtle-like shrub. Nearer the coast the dune is still active and sea spurge and Portland spurge are among the plants growing on the edge. A sand bar joins St Martin’s to the small, uninhabited White Island (see Chapter 7).