Полная версия:

The Isles of Scilly

After David Hunt’s death his friend Will Wagstaff continued the slide shows and guided walks that had become very popular with visitors. Will had, like many other birdwatchers, first come to Scilly on holiday, returning every year from 1975 until he eventually moved to St Mary’s in 1981. For a while Will worked for the Isles of Scilly Environmental Trust (now Wildlife Trust) as field officer until becoming a self-employed tour leader and lecturer. When the Isles of Scilly Bird Group was started in 2000, by a group of resident birdwatchers, Will was the first Honorary President. The ISBG publishes the excellent Isles of Scilly Bird & Natural History Review annually. With a nucleus of resident birders on the islands there has been an increase in observations during the winter months, and indeed throughout the year. This has culminated in the production of another book on the birds of Scilly (Flood et al., in press).

During the twelve years he lived on St Mary’s Peter Robinson carried out ringing and population studies as well as organising surveys on behalf of RSPB, JNCC and English Nature, including ‘Seabird 2000’ and the Breeding Bird Atlas. In 2003 his interest in the islands and their ornithology culminated in the publication of The Birds of the Isles of Scilly. This monumental work reviewed the birds of Scilly from historic references up to the present day.

The Environmental Trust for the Isles of Scilly was set up in 1986. In 2001 the Trust became the Isles of Scilly Wildlife Trust, the forty-seventh member of the Wildlife Trusts partnership in the UK. Based on a total land area of 3,065 hectares at LAT (lowest astronomical tide), the Trust is responsible for 60 per cent of Scilly, with 1,845 ha leased from the Duchy of Cornwall. A very small trust, with only three members of staff in 2006, they have an unusually challenging operation, working in an island situation where all the tools, machinery and volunteers have to be transported by boat from St Mary’s to other islands for a day’s practical management work. During 2000 the Trust took on the disused 1900 Woolpack gun battery on the Garrison, which has now been refurbished and is used as a custom-built volunteer centre with accommodation for thirteen volunteers, including an underground meeting room.

Many films and TV programmes are made on Scilly. Andrew Cooper first visited Scilly in 1981, and made several films about the natural history of the islands, Isles Apart, Secret Nature and Lost Lands of Scilly. He also wrote Secret Nature of the Channel Shore (1992) and Secret Nature of the Isles of Scilly (2006). While working on the films Andrew spent many months in Scilly, observing and filming the wildlife. He was the first person to photograph caravanning behaviour of Scilly shrews. Andrew is Vice-President of the Isles of Scilly Wildlife Trust.

In recent years a number of other naturalists, both local and visiting, have made their unique contributions to our understanding of Scilly’s wildlife. Local diver Mark Groves has written and lectured on the marine life of the islands, photographing many underwater subjects. St Agnes farmer Mike Hicks records and writes about moths, and local restaurateur Bryan Thomas’s superb photographs are a regular feature of the Isles of Scilly Bird Report and Natural History Review. Martin Goodey, who runs Trenoweth Research Station, is also an enthusiastic photographer of birds and insects. For many years Stephen Westcott has been studying the Scilly population of grey seals Halichoerus grypus (Fig. 25). He works from a kayak, which enables him to get very close to the animals with minimal disturbance.

FIG 25. Grey seal among tree mallow. (David Mawer)

Lower plants have not been forgotten, and have been studied by Bryan Edwards (lichens), David Holyoak, Jean Paton and Robert Finch (bryophytes). Insects have been getting more attention too, with the papers by Ian Beavis, and a number of other entomologists, including local birdwatchers in Scilly who have now extended their interests into recording bush-crickets, stick insects and other groups. Molluscs, ferns and plants have also had their disciples. The production of the Isles of Scilly Bird Report and Natural History Review has encouraged visiting and local naturalists to publish their records and papers, making information much more readily available. A number of contributors to the Review have been very generous with information and illustrations for this volume and are acknowledged elsewhere.

CHAPTER 5 St Mary’s

Not a tree to be seen, but there are granite piles on the coast such as I never saw before, and furze-covered hills with larks soaring and singing above them.

George Eliot (1857)

ST MARY’S IS THE largest of the Isles of Scilly at 649 hectares (above MHWS) and approximately 4km x 3km from coast to coast. Only on St Mary’s is there enough metalled road to merit any kind of bus service or any traffic as such. There are just over seventeen kilometres of road that link most of the communities on St Mary’s. Besides being busy with local and farm traffic, the sightseeing buses, the hire bikes and the taxi cabs all use the road to provide a service for the holidaymakers who flock to the island in the summer (bringing your own car to Scilly is not advised).

Away from the sea the interior of the island is gently undulating with a slightly more ‘mainland’ feel due to a largely cultivated landscape with small hamlets scattered among the farms. Many of the fields are arable and often have interesting weed floras, usually including some of the arable plants now becoming increasingly rare in Britain. The field boundaries, consisting of pine windbreaks, evergreen and elm ‘fences’ (hedges), and stone ‘hedges’, all have their particular natural history and landscape features. The unfarmed land, comprising grassland, wetlands and heath, is mostly around the coast. Also around the coastal areas are spectacular rocky headlands, cliffs, sandy bays and dunes. The ‘main’ road forms a figure of eight round the middle of the island, with a few other small sections of made-up road linking the hamlets. Farmland away from the road is generally inaccessible to the general public except were served by footpaths. There is a coastal path round the island and a system of footpaths that mostly link the roads with the coast, or access the nature reserves.

THE BUILT-UP AREA

Around the main harbour on the west of St Mary’s is Hugh Town (Fig. 26), the principal town in the islands, the administrative ‘capital’ where most of the main business of the islands takes place, with the Council offices, shops, banks, hotels, museum and the nearby industrial estate at Porth Mellon. The Council of the Isles of Scilly has unusual responsibilities, and although representing a very small population of approximately 1,600 (c.4,000 in summer) it has virtually the same powers as a county council. The offices of the Duchy of Cornwall (the landlord of the Isles of Scilly), the Wildlife Trust and other organisations are also mainly based in Hugh Town. The passenger ship RMV Scillionian sails from St Mary’s harbour, and with the airport forms the main link with the mainland. The present quay is built over an island, Rat Island, and out into St Mary’s Pool. From the harbour the inter-island launches and the ‘tripper’ boats link with the off-islands and run sightseeing trips.

FIG 26. A view of St Mary’s harbour, Hugh Town and the Garrison, May 2003. (Rosemary Parslow)

Much of the town is on the low-lying land that was originally a sand bar joining the promontory of the Hugh to the rest of St Mary’s between the Pool (harbour) and Porth Cressa. From there the town spreads up the slopes of the Garrison and Church Street. The proximity of the harbour and the beach has resulted in many coastal plants having become residents in the town. Portland spurge Euphorbia portlandica grows at the base and on top of some walls, tiny sea spleenwort Asplenium marinum ferns grow in crevices on many walls and four-leaved allseed Polycarpon tetraphyllum and rock sea-spurrey Spergularia rupicola along cracks in pavements. Some plants have become strongly associated with Hugh Town, including sand rocket Diplotaxis muralis, sweet alyssum Lobularia maritima and cineraria Pericallis hybrida. With all the small gardens around the town many garden plants and more exotic plants are able to escape into alleys and byways, so part of the fun for a botanist wandering around the streets is not knowing what discovery might be waiting around the next corner!

During the summer holiday season Hugh Town can be quite a bustling place. Every morning the holiday people stream down the main streets to the harbour, where they join the queue on the quayside for tickets and then embark on one of the launches that will take them to one of the other inhabited islands or, if the weather is good and the seas calm, on a trip around the Eastern Isles or Annet and the Western Rocks. On the calmest days there will perhaps be a boat going as far as the Bishop Rock lighthouse. This can be an exciting trip that guarantees close views of seabirds and seals. There is always a sea running beyond the Western Rocks, even in the calmest weather, giving the passengers something to boast about in the pub later. But sailing out among the Western Rocks, among the savage beauty of jagged islands and myriad splinters of rock just breaking the surface of the waves, is a graphic reminder of the hazards associated with the sea and Scilly. Reaching Bishop Rock means sailing over another long stretch of restless water beyond the Western Rocks towards the long finger of the lighthouse pointing skywards in the distance. As you sail beneath the lighthouse there is little sign of the rock on which it is built, and looking up at the tower above is an utterly awesome experience. The return of the tripper boats results in a reverse flow back up the main street from the quay as everyone returns for the evening. For a little while now the shops are busy. And if you are a birdwatcher it is time to check the blackboard where bird news is chalked up, hoping all the time you have not missed anything exciting.

On the opposite side of the island to Hugh Town is the hamlet of Old Town (Fig. 27). This was the main town and former harbour (the quay can still be seen) on St Mary’s in medieval times, with a castle where the Governor lived, but it was superseded by the better-fortified Hugh Town. There is little left of Ennor Castle

FIG 27. Old Town harbour with its old granite quay and the church, January 2000. (Rosemary Parslow)

now, just the mound on which it stood; presumably it was demolished and the stone used to build Star Castle. Despite improved sea defences and rebuilding of the sea wall and the road in 1996 it is not unusual to see sand-bags propped up against front doors or seaweed in the street in winter; the lower part of Old Town is another area under constant threat from the sea. Overlooking the Bay is Old Town Church, where the surrounding churchyard, with its different levels and terraces, surrounded by trees, provides a haven for many unusual species of plants. It is impossible to overlook the multi-coloured cinerarias that have escaped from cultivation and rampaged over all the walls, paths and old graves. Other plants growing in the churchyard include grassland species, ferns or garden escapes that find refuge among the gravestones and walls. Migrant birds are often located in the churchyard, and the sheltered conditions also attract many insects and even bats on calm evenings. Some of the nearby fields behind the church also have good arable weed floras. Not far from the church along the edge of the bay is a large isolated rock, Carn Leh, which is an important site for rare lichens.

INLAND ST MARY’S

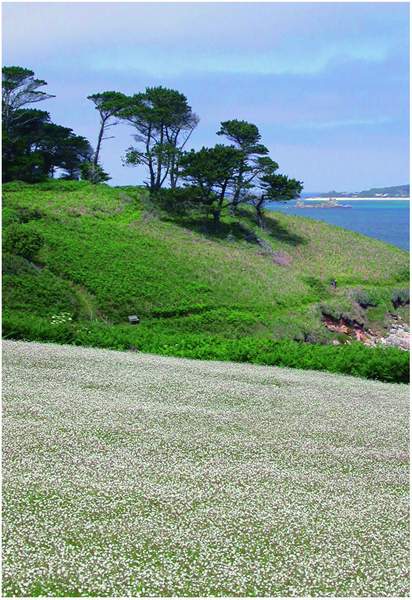

Inland the countryside is slightly undulating farmland served by the ‘main’ road. The island bus service only drives around the main part of the interior, some roads being very narrow. Between the fields, both pasture and flower fields, the boundaries are formed both by stone ‘hedges’ with a rich cover of ferns, grasses and other plants, and by tall, clipped evergreen ‘fences’ (Fig. 28). Many of the roadsides are fringed with elm trees, predominately Dutch elm Ulmus x hollandica. In sheltered areas the elm trees are able to grow tall, those in the valley of Holy Vale and around Maypole being some of the finest. Crossing the island are several conifer shelterbelts (Fig. 29), which in places include the distinctive silhouettes of Monterey pines Pinus radiata, where remnants of earlier plantings still survive.

FIG 28. Inland St Mary’s: evergreen fences near Porth Hellick, August 2006. (Rosemary Parslow)

FIG 29. A pine shelterbelt and an arable field covered in corn spurrey near Watermill Cove, June 2005. (Rosemary Parslow)

CLIFFS AND COASTS

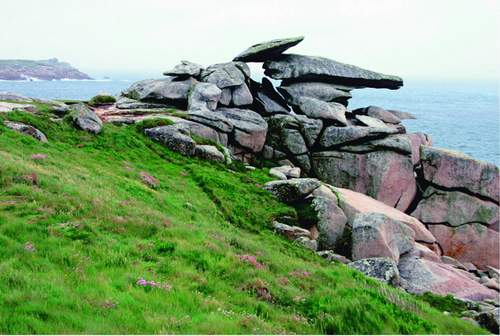

Most of the coastland of St Mary’s consists of cliffs, not very high, but spectacular enough at times when gales drive the waves in onto the rocks. In places a few small bays break the coastline and there are two large promontories, the Garrison in the southwest and Peninnis Head in the south. In many places there are granite carns (tors) eroded into extraordinary, fantastical shapes: Pulpit Rock, Tooth Rock and the Loaded Camel are just a few well-known examples (Fig. 30). Above the cliffs and steep slopes along the west coast are typical maritime-cliff plant communities, dense bracken communities on the deeper soils, heather-dominated heath and short grassland on the shallower soils and over rocks. Among the shrub species growing on the coast are both common gorse Ulex europaeus and western gorse U. gallii and scattered patches of broom. Along the coastal edge the maritime grassland sometimes extends inland as a series of pastures that in summer are bright with the yellow flowers of common cat’s-ear Hypochaeris radicata amid a colourful mixture of grasses and forbs.

At Carn Morval, on the steepest part of the coast, part of the nine-hole golf course is perched on a rocky promontory above the slope. The rest of the

FIG 30. Pulpit Rock on Peninnis Head, St Mary’s, May 2006. (Richard Green)

FIG 31. Bant’s Carn on Halangy Down, St Mary’s, probably the best known of the Bronze Age entrance graves in the Isles of Scilly. March 2006. (Rosemary Parslow)

golf course sits high above at the top of the slope, where its manicured greens frequently attract migrating birds. As with the airfield this can be very frustrating for the excluded birdwatchers! Beyond Carn Morval is another area of coastal heath at Halangy Down, where in a carefully tended area of grass and mown heather is an important archaeological site managed by English Heritage. These are the remains of an Iron Age/Romano-British village settlement of many small buildings, now marked only by low walls, and the ridges denoting earlier field systems on the nearby slopes. At the top of the hill is Bant’s Carn, a large Bronze Age entrance grave, one of the best examples of its type in Scilly (Fig. 31). The whole closely managed and mown site is quite species-rich, and even the walls and banks of the ancient village have an interesting flora that includes western gorse, hairy bird’s-foot-trefoil Lotus subbiflorus, subterranean clover Trifolium subterraneum growing on and among the stones. The turf is also full of chamomile Chamaemelum nobile, deliciously scenting the air as you explore. Ruts on some of the paths nearby have a miniature flora of toad rush Juncus bufonius and sometimes in spring an unusual but very inconspicuous alien called Scilly pigmyweed Crassula decumbens. This is a South African species, probably introduced accidentally with other plants to the nearby Bant’s Carn farm. Only very recently has it apparently started to spread away from the farm, and it can now sometimes be seen on the path leading up the hill towards the golf course.

Just beyond Bant’s Carn Farm the land slopes down to the sand dunes that form the northern tip of the island at Bar Point. The dune system is very disturbed. Part has been quarried and there is also a part used as a dump. Much of the dune system has become colonised by bracken and bramble Rubus agg. communities. There are areas of scattered gorse bushes, where both the rare balm-leaved figwort and Babington’s leek Allium ampeloprasum var. babingtonii can be found. Closer to the quarry and the dump some plants of garden origin have become established so that you can come upon bear’s breech Acanthus mollis, montbretia Crocosmia x crocosmiiflora, fennel Foeniculum vulgare and even the giant rhubarb plant Gunnera tinctori. Somewhere in the dunes near here the fern moonwort Botrychium lunaria used to grow under the bracken. It was last recorded by Lousley in 1940, and may have been lost when the area suffered major disturbance some time after 1954, from various activities including relaying the submarine telegraph cable, winning sand and dumping rubbish. Since then, despite much searching, there has been no further sign of the moonwort.

More areas of bracken communities follow the northern coast of the island all the way round from Bar Point to Innisidgen, Helvear Down, and right down to the narrow inlet at Watermill Cove. On this northern part of the coast there are areas of pine shelterbelts, which extend right round to the eastern side of the island, and large stretches of beautiful heathland near the coast. Patches of tall gorse with an understorey of lower heathland plants grow along the sides of the path as it continues around the coast, also appearing anywhere there are breaks in the bracken cover.

Close to the coast path are two impressive entrance graves, Innisidgen Upper Chamber and Innisidgen Lower Chamber. Around the barrows the vegetation is kept regularly mown, resulting in species-rich lawns of grasses, sedges and typical heathland plants, demonstrating the potential richness of the vegetation if the surrounding overgrown areas could be restored and perhaps maintained by grazing. Beside the path what appears to be a low wall is the remains of the former Civil War breastworks, half-buried in dense vegetation. As the path drops down the hill into Watermill Cove, the Watermill Stream runs into the sea through mats of dense hemlock water-dropwort, fool’s-water-cress Apium nodiflorum and a group of grey sallow Salix cinerea oleifolia trees. Just round the corner there are steep cliff exposures along the section of the inlet at Tregear’s Porth, an important geological site, notified as the Watermill Cove Geological Conservation Review site. From here the path continues along the coast, and another one follows the Watermill Stream inland along the heavily shaded lane lined with ferns.

The mosaic of heathland, gorse, bracken and bramble continues along the coast past Mount Todden. In places there are more sections of Civil War fortifications and much earlier archaeological sites. Below the cliffs at Darity’s Hole is a very important underwater site where many unusual marine species have been recorded. Towards Deep Point there is an area of ‘waved heath’ (see Chapter 10), and elsewhere there are patches of heather still beneath the taller bracken, as well as around rocks and paths. Where there is a freshwater seepage down one of the slopes, the understorey consists of broad buckler fern Dryopteris dilitata, occasional soft shield-fern Polystichum setiferum and marsh pennywort Hydrocotyle vulgaris. Near Deep Point in an area of short coastal turf careful searching may reveal another rare lichen, ciliate strap-lichen Heterodermia leucomela. It was at Deep Point that at one time the islanders disposed of cars and other rubbish over the cliff. Although the practice has been stopped, the remains of vehicles at the bottom of the cliff in deep water apparently now support a rich marine flora and fauna! At Porth Wreck there is a former quarry in the cliff, often the place to find unusual casual plants.

Porth Hellick Down is one of the largest areas of wind-pruned waved heath on St Mary’s. Much of the gorse among the heathers in the area is western gorse, with flowers a deeper golden colour than the yellow of common gorse. Around the Porth Hellick barrow Ancient Monument is a closely mown circle of grass starred with flowers of chamomile, tormentil Potentilla erecta and lousewort Pedicularis sylvestris, as well as stunted bell heather and other typical heathland plants. Similar vegetation covers the burial mound with a dense sward of low grasses and flowers.

South of the deep bay of Porth Hellick lies the open heathland of Salakee Down with the rather eroded outline of Giant’s Castle, an Iron Age hill fort. At Salakee Down is a beautiful stretch of coastal grassland and waved heath, again with common gorse and western gorse, bell heather, ling and other heathland species (Fig. 32). Close to the Giant’s Castle are a number of small damp and seasonally waterlogged pits with wetland plants including lesser spearwort Ranunculus flammula, bulbous Juncus bulbosus and soft rushes J. effusus as well as small adder’s-tongue fern Ophioglossum azoricum and royal fern Osmunda regalis. Further towards Porth Hellick are more areas of waved heath, where the heather is deeply channelled into ridges by the wind. These coastal areas are among the best places to look out for migrating birds, especially wheatears Oenanthe oenanthe, and even migrating butterflies such as clouded yellow Colias croceus. These ‘downs’ are also home to green tiger beetles Cicindela campestris, rose chafers Cetonia aurata and other insects.

Between Giant’s Castle and Blue Carn one of the runways of the airport

FIG 32. An example of ‘waved heath’ can be seen near Giant’s Castle, an Iron Age cliff castle. Salakee Down, June 2002. (Rosemary Parslow)

interposes itself into the cliff edge. Not a place to linger, although the system of traffic lights at the top of the slope on the edge of the cliff warns of the imminent approach or departure of aircraft. The airport is one of largest areas of open grassland on St Mary’s, but access is restricted due to safety considerations. Most galling for the birdwatchers, as the mown grass attracts rare plovers, wheatears and other birds of open habitats. Usually some kind of viewing place is negotiated each autumn so that birdwatchers can see part of the airfield without interfering with the business of flying.

As you round the corner into Old Town Bay you pass the narrow rocky promontory of Tolman Point, between the bay and Porth Minick. Here there are maritime grassland and cliff communities and a small triangular group of planted shrubs including shrubby orache Atriplex halimus. On the Old Town side of the headland Hottentot fig and rosy dewplant Drosanthemum roseum grow over the rocks and grassland, in places completely submerging native species.