Полная версия:

The Isles of Scilly

ELIZABETHAN SCILLY

It was Queen Elizabeth I who in 1570 leased Scilly to Francis Godolphin, initially for 38 years at £20 per annum. This link with the Godolphins was to continue, more or less, until the heir to the Godolphins, the then Duke of Leeds, gave up the lease in 1831 and the Duchy of Cornwall resumed control. The next period in Scilly’s history seems to have been a nervous time, with the threat of invasion ever in the offing. Despite this nothing much was done to prepare to repel possible attack during the early years of Queen Elizabeth’s reign, despite, one would have thought, there being a very real threat of invasion by the Spanish Armada. Then, near the end of Queen Elizabeth’s reign, Star Castle was built, followed by the first defences on what is now the Garrison.

THE CIVIL WAR IN SCILLY

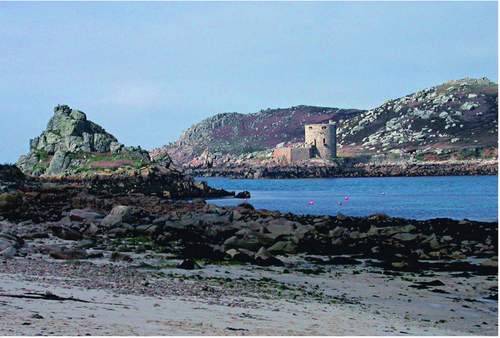

During the Civil War the Garrison defences were improved and King Charles’s Castle was built on Tresco to defend the harbour at New Grimsby. The islands passed from Royalist to Parliamentary hands and back again. Unfortunately the Royalist command by Sir Richard Grenville led to the islands becoming a base for piracy, which annoyed not only Parliament but also the Dutch. It was not long before both the English fleet and the Dutch set sail to capture the Isles of Scilly. Eventually the Royalists surrendered to Admiral Blake after the Garrison had come under relentless fire from his ships and from Oliver’s Battery, which had been built on Tresco, and the Dutch backed off. Later, another fortification known as Cromwell’s Castle was built in a better position overlooking the harbour of New Grimsby (Fig. 15), to ward off further attack by the Dutch (the fortifications at Charles’s Castle on the hill overlooking Tresco Channel being so badly placed as to be useless for defence).

In 1660 the monarchy was restored, and the Godolphins returned to Scilly. But it does not seem to have been quiet for long. Spain became a threat again, and in the second half of the century there was a massive programme of building on the promontory of the Garrison and elsewhere to strengthen the defences.

Turk (1967) refers to a comment by Richard Ligon in the True and Exact History of the Island of Barbadoes (1673), where he mentions puffins ‘which we have

FIG 15. Cromwell’s Castle and the ruins of King Charles’s Castle, Tresco. Photographed from near Hangman’s Island, Bryher, March 2005. (Rosemary Parslow)

from the Isles of Scilly…this kind of food is only fit for servants’. So clearly puffins (or shearwaters, which were considered a delicacy) were being exported from Scilly at the time.

NAPOLEONIC WARS

For the next century life in the Isles of Scilly remained quiet once again, and very little of note happened. During the Napoleonic Wars (1803-15) Scilly again seemed vulnerable and some additional defences were built. Life in Scilly was very hard at this time. Attempts to relieve the poverty and distress of the islanders by establishing a pilchard and mackerel fishery were not very successful, and famine conditions continued for some years, especially on the off-islands (Bowley, 1990). In 1834, just three years after taking over the lease from the Godolphins, the Duchy of Cornwall leased the Isles of Scilly to Augustus Smith in an effort to get rid of what had become an acute embarrassment to them. The arrival of Augustus Smith was to have a profound effect on Scilly and the Scillonians, as well as on the flora of the islands (see Chapter 13). In 1863 the Garrison defence force was eventually disbanded.

WORLD WAR I AND WORLD WAR II

During the two World Wars Scilly was host to large numbers of servicemen, and the islands were considered very vulnerable to attack or invasion. In World War I a naval seaplane base was established, first on St Mary’s but later transferred to Tresco, and almost a thousand men were based on the Garrison on St Mary’s. During World War II Scilly became important as a lookout post for German submarines, and additional fortifications were built on St Mary’s, with fighter planes and air-sea rescue launches stationed there. Even so a number of air raids occurred and there was some bomb damage on the islands. It was just prior to World War II that the population of Scilly reached 2,618, the highest yet (excluding temporary summer populations now). This was also the time when the greatest amount of arable land was under cultivation (Lousley, 1971).

THE KELP INDUSTRY

For some hundred and fifty years from the late seventeenth to the early nineteenth century the burning of kelp was an important local industry that involved almost every family on Scilly (Fig. 16). When kelp burning was in progress, ‘wreaths of smoke rising amidst the dun verdure and hoary carns of these pretty isles’ apparently made them look all the more ‘pleasing and picturesque’ (Woodley, 1822). This might have seemed picturesque from a safe distance, but it is known that the clouds of acrid smoke polluted the air and stank out the houses and the washing lines for weeks on end. James Nance introduced kelp burning to Scilly in 1684, at a time when their more ‘usual’ means of livelihood, smuggling and wrecking, had been curtailed by the introduction of lighthouses and a customs house (Over, 1987). Activities such as collecting the seaweed, stacking it to dry and processing it would have involved the whole family. When it was burned it produced soda ash, which at the time was essential for the making of glass. Although the seaweeds collected were generally called ‘kelp’, they were mostly different species of the large wracks. The species mostly involved were the following:

knotted wrack Ascophyllum nodosum

bladder wrack Fucus vesciculosus

serrated wrack Fucus serratus

driftweed Laminaria cloustini

sugar wrack Laminaria saccharina

driftweed Laminaria digitata

According to Over (1987) only the fucoid seaweeds would have been a significant part of the harvest in Scilly because of the difficulty of collecting the big Laminaria seaweeds that grow in deeper water. However, storms frequently drive masses of seaweed onto the shore where it can be collected, and use of a boat could also have made it possible to access the Laminaria beds at low water springs.

Starting in March, families would collect the seaweed and carry it to places where it could be heaped up and dried. Deep stone-lined pits just above the shore were used to burn the seaweed, and these were kept going continually until the mass of weed began to liquefy, when it was stirred in a particular way and left to solidify. This lump of ‘kelp ash’ was eventually shipped off to Bristol or Gloucester to be processed for use in glass making, as well as for the manufacture of soap and alum.

It was necessary to haul huge amounts of the algae up the shore (it took

FIG 16. Burning kelp in pits by the shore to produce soda ash was a stinking and unpleasant task. The industry lasted for some 150 years until about 1835. (Gibson collection)

some 3-4 tonnes of weed to produce 127-152kg of crude ash before refinement), which could mean a family was collecting something in the order 268 tonnes of wet seaweed in a year. This would have had a considerable denuding effect on the shore and must have been quite devastating to those species associated with the algae. In some years it seems the crop of algae was not enough to go round. There is some indirect evidence of this in the court cases recorded at the time that refer to islanders infringing the rights of others by taking kelp they did not own. By law, ‘no person was to cut…off an inhabited island where a horse could go among the rocks at low tide’, presumably as these stands of kelp were already allotted. One would imagine that when the kelp was not so abundant and families became hard-pressed to find enough to fulfil their requirements, life must have been increasingly hard (Over, 1987). Kelp collecting was not confined to the inhabited islands: for example, some islanders spent the summers on Great Ganilly collecting seaweed.

The kelp industry spread all around the coasts of Britain, although it was not initially popular everywhere; in Orkney, the islanders of Stronsay rioted in 1762. But soon the high prices paid for the soda ash ensured that the practice became the main means of livelihood for many coastal and island communities (Berry, 1985). This was helped by wars and protective tariffs that blocked off the usual foreign sources of alkali, particularly ‘barilla’ glasswort Salicornia sp. from Spain. Eventually the industry fell into decline after the Napoleonic Wars, and it never recovered once it was found easier to manufacture soda chemically. Presumably the shores soon recovered and the algae soon grew again unchecked.

There are few signs now of this extraordinary industry, just a few abandoned kelp pits above the shoreline and the remains of a handful of quays from which the kelp was exported. There is a good example of a kelp pit below Kittern Hill on Gugh, with others on White Island, St Martin’s, on St Martin’s itself and on St Mary’s – and there are several on Toll’s Island, St Mary’s. These are now just shallow stone-lined basins in the turf, not as deep as they would have been when in use. There are ruined quays at Pendrathen and on Teän, as well as on White Island, on Toll’s Island, and at Watermill (Bowley, 1990).

Seaweed was also used to manure the fields, a practice which was in use until quite recently in the 1960s and 1970s. In the past both sheep and cattle would also graze on ‘oar weed’ (Borlase, 1756). A few farmers and householders still take seaweed to use on their crops, usually composting it until it has rotted down and the rain has washed out some of the salt.

PIRACY AND SMUGGLING

Scilly had been a base for pirates during the early twelfth century, at which time it was left to the resident monks to attempt to control the practice. Later, Lord Admiral Seymour (the widower of Catherine Parr, the surviving queen of King Henry VIII) was hanged in 1549 for piracy and treason after spending only two years on Scilly. Smuggling has long been associated with the southwestern counties of England, and Scilly is uniquely suited to it, with plenty of hidden places around the islands and fleets of gigs capable of sailing to the coast of France. At one time smuggling was one of the main occupations of the islanders, alongside the legitimate occupations such as piloting.

WRECKS

Over the centuries there have been hundreds of wrecks in the Isles of Scilly. Besides the accidental passengers they may have carried, such as rats, their spilled cargoes frequently washed ashore and may have introduced some plants and animals to the islands. From the published lists of cargoes we know the

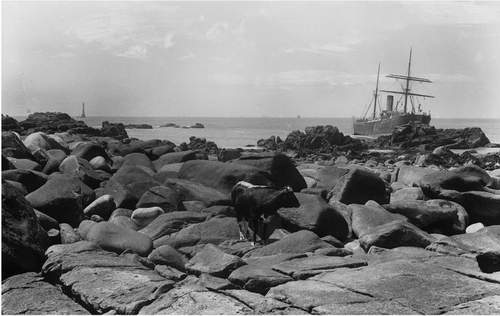

FIG 17. The SS Castleford ran aground on the Crebawethans in fog in June 1887. Most of the cattle from the ship were later taken to Annet. (Gibson collection)

ships were frequently carrying hides, corn and seeds. When cattle were rescued from wrecks we know that the survivors were landed on uninhabited islands, Samson in one case and Annet in another (Fig. 17). One supposes the islanders would also have taken supplementary feed to the cattle during their enforced marooning. This may have resulted in grasses germinating from fallen seed from the hay.

One animal that may have reached Scilly as a stowaway is the wood mouse, now resident on St Mary’s and Tresco. The black rat Rattus rattus may also have arrived by boat. At one time they had colonised Samson and would have been on many of the islands; later the brown rat R. norvegicus also presumably arrived on ships.

FARMING

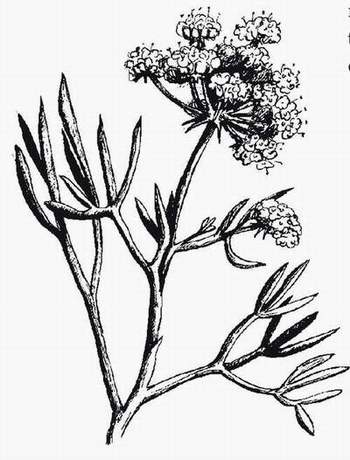

The observations of the many people who visited the Isles of Scilly over the centuries give only the most tantalisingly incomplete account of the life of the people at the time, and very little detail about the farming. Maddeningly, most authors have not confined themselves to their own first-hand experiences but have quoted liberally, repeating, frequently without acknowledgement, the observations of their predecessors. One gentleman who visited the islands, the Reverend George Woodley (1822), was also very scathing about his predecessors, Robert Heath, who spent a year on the islands, and John Troutbeck, who was the chaplain of the islands. Troutbeck published his account in 1794, but his information in turn appears to be based on the reports of Robert Heath (1750). From all the accounts it seems that one of the most important crops at the time was potatoes in great quantity, and in good years the islanders might get two crops a year. The islands were not very good for growing wheat, but barley, rye, oats, pillas (an oat-like grain eaten as a porridge, which even up to quite recent times was being grown alongside corn and root crops), peas, beans and roots all did well. Salads, gooseberries, currants, raspberries, strawberries – anything that can be sheltered below walls could be grown. Garlic, both cultivated and wild, samphire for distilling and pickling, all grew locally. Rock samphire Crithmum maritimum still grows around all rocky shores (Fig. 18), but it is no longer pickled and exported in small casks (Heath, 1750; Woodley, 1822).

According to Woodley (1822) the local horses were small and had to survive on poor fare that included gorse, which they bruised with their hooves before eating, the sheep were small, long-legged animals similar to those on the Scottish islands, and both the sheep and the small black cattle subsisted on seaweed when

FIG 18. Rock samphire collected from the shore was once used for pickling and distilling. (Rosemary Parslow)

there was no hay for them. The local hogs would also have to be fed on seaweed and even limpets at times, causing their flesh to be reddish in colour and giving them an unpleasant fishy taste.

Several of the uninhabited islands were used as summer grazing, as well as places where there were colonies of rabbits Oryctolagus cuniculus and seabirds that could be utilised to provide rabbit meat and gulls’ eggs. Sheep and deer were grazing on the Garrison, St Mary’s, when Walter White (1855) was there in the mid nineteenth century. He also describes hayfields, arable fields of grain, root crops and potatoes (the latter were sent to market at Covent Garden).

Sheep were kept on the islands until the beginning of the twentieth century, and although there are now very few they have never completely died out. There are sheep pictured beside the Punchbowl Rock on Wingletang, St Agnes (Mothersole, 1919), and the last time sheep were on the island was in 1926 at Troy Town. Goats were kept throughout the centuries and are still present on several holdings on the islands. Donkeys were very common at one time and were used to carry baskets of kelp up from the beach. The Gugh donkey Cuckoo became famous when Leslie Thomas wrote about him in Some Lovely Islands (1968). Until the mid-1950s horses were still used on some farms, but the only horses now on the islands are for riding, other than the Shetland ponies that are being used for conservation grazing on some of the important nature conservation sites.

One curious industry between about 1840 and 1880 was straw-plaiting for making hats (Matthews, 1960). Besides using wheat and rye straw various hollow-stemmed grasses were also utilised, including crested dog’s-tail Cynosurus cristatus and yellow oatgrass Trisetum flavescens. Crested dog’s-tail is still a common grass in the islands and yellow oatgrass was found on Teän as a relict of farming but has now disappeared.

THE EVACUATION OF SAMSON

Sir Walter Besant’s romantic tale of Armorel of Lyonesse (1890) has coloured the island with a totally unrealistic, fictitious past; there is even a ruined cottage on the island reputed to be Armorel’s cottage. Sadly the reality is quite different: although the island was inhabited for many years, life for the islanders was hard and eventually Samson was abandoned in 1853-5 during the ‘reign’ of Augustus Smith.

Samson has many archaeological sites from the Bronze Age, mostly burial monuments but also a field system and hut circles on the south side of South Hill and another field system on North Hill. At some time the island became deserted and may have then been uninhabited for centuries. Finds of pottery from below dunes in East Porth may point to a lone cleric or other person living there in the thirteenth century (Thomas, 1985). In 1669 five people were living on Samson, possibly in a single dwelling, when Cosmo III, Grand Duke of Tuscany, made his short visit to Scilly. At some time after this the population rose to some thirty or forty people; between about 1755 and 1780 was probably their most settled time.

The main difficulty with living on Samson was the very poor water supply. The wells were slow or silted up, and the water was bad. At times water had to be fetched in barrels from Bryher or Tresco. It must have been a hard existence, based on fishing, which was the islanders’ major occupation, growing a few basic crops, corn and potatoes, and keeping stock. From the limpet shell middens they left behind there clearly were difficult times, when shellfish became a major part of their diet. Other sources of income, piloting and kelp burning, were important but never enough to sustain the population.

At the time of the greatest population, in 1829, there were nine cottages and thirty-seven people. The islanders grew their crops in small strip fields or lynchets. Even their tiny fields were subdivided into even tinier plots, in keeping with the custom of the time that when a man died his holding would be divided between his sons and sometimes also widowed daughters and daughters-in-law. The boundaries of these divisions were often based on earlier lynchets or were laid out strip-fashion. There were no trees for fuel so turf would have been cut from the tops of the hills (the top of North Hill is still very bare to this day, possibly from turf cutting or later fires). It was reported by Captain Robert Welbank, a Trinity House visitor in 1841, that both bracken and dried seaweed were used for fuel, and any driftwood would also be precious (Thomas, 1985). At that time there were twenty-nine people living on Samson, seven being children. There were only seven households: four farmers, one farmer’s widow, two fishermen. By this time Augustus Smith was introducing his reforms and imposing them on the other islanders in Scilly, and he soon prevailed on the tenants on Samson to relocate to St Mary’s or other islands, with the benefits of education for their children and better occupation for themselves. The last inhabitant is said to have left in 1855. After that the houses would have been stripped; they soon began to collapse and are now all ruins (Fig. 19). Shortly after the evacuation Augustus Smith built a large stone-walled enclosure around the top of South Hill in which he attempted to keep a herd of fallow deer Dama dama. The deer, however, soon escaped and tried to get to Tresco. Some accounts say they drowned, but the distance is not very great and at low tide they might have walked across. A herd of cattle was also grazed on the island.

FIG 19. Ruined cottages on Samson, photographed during a visit to the island by a party of geology students in the 1890s. (Gibson collection)

FIG 20. On Samson primroses still grow near the ruins of the cottages. (Rosemary Parslow)

Besides their ruined dwellings, kitchen middens and other artefacts, the inhabitants of Samson left other mementos. They left behind several trees, tamarisk Tamarix gallica, elder, privet Ligustrum ovalifolium hedges (the latter now apparently lost, as only wild privet L. vulgare is found on the island today), burdock Arctium minus and primroses Primula vulgaris, which are still found not far from the ruins (Fig. 20). They also left the stone hedges that marked the boundaries of some of their tiny fields. Despite the history of Samson, Kay (1956) was of the opinion that it was the sort of place where a couple of enterprising young men could earn a healthy living with a flower farm and a few cattle. He had earlier heard of a Scillonian who had been offered a deal on the island, £10 per year rent for twenty years, then £250 per year afterwards. His friend did not take up the offer, his new wife not fancying a life on an uninhabited island – and it is probably fortunate for Samson that it has remained uninhabited by humans.

CHAPTER 4 Naturalists and Natural History

A singular circumstance has been remarked with respect of these birds [woodcock], which, during the prevalence of strong gales in a direction varying from East to North, are generally found here before they are discovered in England, and are first seen about the Eastern Islands and the neighbouring cliffs. May not this circumstance tend to elucidate the enquiries of the naturalist relative to their migration?

George Woodley (1822)

SOME OF THE early visitors to Scilly played their part in contributing to our knowledge of the flora and fauna of the islands, and some of them will be mentioned in these pages. Today, Scilly is a popular holiday destination, and many naturalists visit the islands. Universities and other groups also make field trips to Scilly to study various aspects of the ecology, especially the marine biology. Another large group that has contributed greatly to scientific information about Scilly is the diverse body of professional biologists who continue to carry out surveys and all manner of research projects on the flora and fauna, often on behalf of statutory agencies such as English Nature. Clearly there are now too many people to do more than acknowledge the contribution of a few of their number. The selection is necessarily subjective, covering mainly the earlier naturalists, but also people I know, and those whose work I have drawn upon. It is becoming increasingly difficult to acknowledge everyone who has added to our knowledge of the natural history of Scilly – especially when it comes to birds and plants. So I hope those mentioned here will stand as representative of the rest.

Prior to the early 1900s the only notes on the natural history of the Isles of Scilly were occasional comments in reports of broader interest such as that by Robert Heath (1750), after he had spent about a year in Scilly. When J. E. (‘Ted’) Lousley published his Flora in 1971 he gave a comprehensive account of botanists who had contributed to the discovery of the flora of the islands. In this he commented on the paucity of botanical records from Scilly before the early twentieth century, which he put down to the inaccessibility of the islands. So when Sir William Hooker, the first Director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, spent ten days in Scilly in spring 1813, visiting all the larger islands and making only the most miserable of comments on a few species he had observed, Lousley is scathing in his assessment of the great opportunity lost.