Полная версия:

Food for Free

Barberry dressing

The berries are juicy and pleasantly tart, and make an excellent jelly with lamb. But it is a shame not to make use of their shape and colour, and the sense they give of being concentrated capsules of juice. Many of the most interesting uses of barberry have been partly decorative. They can be used as a dressing for roast duck – they burst during the cooking and baste the meat with their juice. Mrs Beeton suggests that ‘the berries arranged on bunches of nice curled parsley make an exceedingly pretty garnish for white meats’. Some cooks float the berries on top of fruit salads.

Candied barberries

The berries can be candied for longer storage. Boil sugar to the syrup point, then dip the bunches of barberry into the syrup for 5 hours. Remove the berries, boil the syrup to the candy point and return the berries for a few minutes. Then remove them, and allow to set.

© ImageBroker/Imagebroker/FLPA

© Hartmut Schmidt/Imagebroker/FLPA

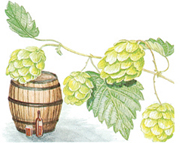

Hop Humulus lupulus

A familiar perennial climber, 3–6 m (10–20 ft) high. Locally frequent in hedges, woodland edges and damp thickets, especially in the southern half of England. Flowers July to August.

The green, cone-like female flowers of the hop have been used in mainland Europe for flavouring beer since the ninth century. Although the plant is a British native, hops were not used for brewing in this country until the fifteenth century. Even then there was considerable opposition to their addition to the old ale recipes, and it was another hundred years before hop-growing became a commercial operation.

Wild hops can be used for home brewing, but a more intriguing and possibly older custom makes use of the very young shoots and leaves, picked not later than May. They may be an ancient wild vegetable, but most of the recipes came into being as a way of making frugal use of the mass of trimmings produced when the hop plantations were pruned in the spring.

The shoots can be chopped up and simmered in butter as a sauce, added to soups and omelettes, or, most popularly, cooked like asparagus. For the latter, strip the young shoots of the larger leaves, tie them in bundles and soak in salt water for an hour, drain and then plunge into boiling water for a few minutes until just tender. Serve with molten butter.

Hop frittata

Frittata is an Italian recipe that can be used with many of the green-stem wild vegetables in this book – for example, asparagus, wild garlic, thistles and bramble shoots. A frittata should be much more solid than an omelette, and can be served hot or cold.

2 handfuls of hop shoots

1 small onion

4 eggs

1 dsp dried breadcrumbs

1 dsp parmesan cheese

Parsley

• Beat the eggs with seasoning to taste, and with the breadcrumbs and parmesan cheese. Chop the hop shoots into roughly 5 cm (2 inch) lengths and fry with the chopped onion in a little olive oil in a heavy pan until they have both begun to brown.

• Add the beaten egg mixture and simmer over a low heat. In about four or five minutes the frittata should have set.

• Take a large plate, cover the pan and turn over so that the frittata settles onto it, slide it back into the pan, and simmer until the other side is brown.

Walnut Juglans regia

Deciduous tree, up to 30 m (100 ft) high, with grey, fissured bark. Leaves are odd-pinnate, with 5 to 9 leaflets. Catkins followed by flowers. Nuts ripen in September.

The walnut is a native of southern Europe, introduced to this country some 500 years ago for its wood and its fruit. Although not quick to spread outside cultivation, there are some self-sown trees in warm spots in the south, and nuts can be carried away from the parent trees by birds and mammals.

Walnuts are best when they are fairly ripe and dry, in late October and November. Before this, the young ‘wet’ walnuts are rather tasteless. If you wish to pick them young, do so in July whilst they are still green and make pickle from them. They should be soft enough to pass a skewer through. Prick them lightly with a fork to allow the pickle to permeate the skin, and leave them to stand in strong brine for about a week, until they are quite black. Drain and wash them and let them dry for two or three days more. Pack them into jars and cover them with hot pickling vinegar. Seal the jars and allow to stand for at least a month before eating.

Mushroom cutlets with walnut cream sauce

Chop the mushrooms finely, cook in a little butter and drain. Soak 125 g (5 oz) of soft breadcrumbs in milk and squeeze dry. Dice and sauté an onion, beat together two eggs and chop some parsley. Combine all the ingredients, form into cutlets and fry in oil. Finally, chop the walnuts with a little more parsley, blend with cream and season.

© cipolla/Imagebroker/FLPA, © Peter Wilson/FLPA, © Bob Gibbons/FLPA, © Marcus Webb/FLPA

© Justus de Cuveland/Imagebroker/FLPA

Beech Fagus sylvatica

Widespread and common throughout the British Isles, especially on chalky soils. A stately tree, up to 40 m (130 ft), with smooth grey bark and leaves of a bright, translucent green. Nuts in September and October, four inside a prickly brown husk. When ripe this opens into four lobes, thus liberating the brown, three-sided nuts.

Beech dominates the chalk soils of southern England and is associated with a number of species of fungi. It is a native species, and has long provided a source of fuel, although it did not gain popularity as a material for furniture until the eighteenth century. Since then it has become extremely popular in the kitchen – albeit for building kitchen units rather than for its culinary delights.

However, the botanical name Fagus originates from a Greek word meaning to eat, though in the case of the beech this is likely to have referred to pigs rather than to humans. This is not to say that beechmast – the usual term for the nuts – is disagreeable. Raw, or roasted and salted, it tastes not unlike young walnut. But the nuts are very small, and the collection and peeling of enough to make an acceptable meal is a tiresome business.

This is also an obstacle to the rather more interesting use of beechmast as a source of vegetable oil. Although I have never tried the extraction process myself, mainly because of a lack of suitable equipment, it has been widely used in mainland Europe, particularly in times of economic hardship, such as in Germany between the two World Wars. Although beech trees generally only fruit every three or four years, each tree produces a prodigious quantity of mast, and there is rarely any difficulty in finding enough. It should be gathered as early as possible, before the squirrels have taken it, and before it has had a chance to dry out. The three-faced nuts should be cleaned of any remaining husks, dirt or leaves and then ground, shells and all, in a small oil-mill. (For those with patience, a mincing machine or a strong blender should work as well.) The resulting pulp should be put inside a fine muslin bag and then in a press or under a heavy weight to extract the oil.

For those able to get this far, the results should be worthwhile. Every 500 g (1 lb) of nuts yields as much as 85 ml (3 fl oz) of oil. The oil itself is rich in fats and proteins, and provided it is stored in well-sealed containers it will keep fresh considerably longer than many other vegetable fats. Beechnut oil can be used for salads or for frying, like any other cooking oil. Its most exotic application is probably beechnut butter, which is still made in some rural districts in the USA, and for which there was a patent issued in this country during the reign of George I. In April the young leaves of the beech tree are almost translucent. They shine in the sun from the light passing through them. To touch they are silky, and tear like delicately thin rubber. It is difficult not to want to chew a few as you walk through a beechwood in spring. And, fresh from the tree, they are indeed a fine salad vegetable, as sweet as a mild cabbage though much softer in texture.

Beech-leaf noyau

An unusual way of utilising beech leaves is to make a potent liqueur called beech-leaf noyau. This probably originated in the Chilterns, where large beechwoods were managed in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to service the chair-making trade. Pack an earthenware or glass jar about nine-tenths full of young, clean leaves. Pour gin into the jar, pressing the leaves down all the time, until they are just covered. Leave to steep for about a fortnight. Then strain off the gin, which will by now have caught the brilliant green of the leaves. To every 500 ml (1 pint) of gin add about 300 g (12 oz) of sugar (more if you like your liqueurs very syrupy) dissolved in 250 ml (½ pint) of boiling water, and a dash of brandy. Mix the warm syrup with the gin and bottle as soon as cold. The result is a thickish, sweet spirit, mild and slightly oily to taste, like sake.

© Derek Middleton/FLPA

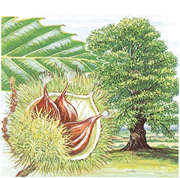

Sweet Chestnut Castanea sativa

Well distributed throughout England, though scattered in Scotland. Common in woods and parks. A tall, straight tree, up to 30 m (100 ft), with single spear-shaped serrated leaves. Nuts in October and November, two or three carried in spherical green cases covered with long spines.

A nut to get your teeth into. And a harvest to get your hands into, if the year is good and the nuts thick enough on the ground to warrant a small sack rather than a basket. Although the tree was in all probability introduced to this country by the Romans, nothing seems more English than gathering and roasting chestnuts on fine autumn afternoons.

The best chestnut trees are the straight, old ones whose leaves turn brown early. Do not confuse them with horse chestnuts (Aesculus hippocastanum), whose inedible conkers look rather similar to sweet chestnuts inside their spiny husks. In fact the trees are not related, Castanea sativa being more closely related to the oak. They will be covered with the prickly fruit as early as September, and small specimens of the nuts to come will be blown down early in the next month. Ignore them, unless you can find some bright green ones which have just fallen. They are undeveloped and will shrivel within a day or two.

The ripe nuts begin to fall late in October, and can be helped on their way with a few judiciously thrown sticks. Opening the prickly husks can be a painful business, and for the early part of the crop it is as well to take a pair of gloves and some strong boots, the latter for splitting the husks underfoot, the former for extricating the fruits. The polished brown surface of the ripe nuts uncovered by the split husk is positively alluring. You will want to stamp on every husk you see, and rummage down through the leaves and spines to see if the reward is glinting there.

Don’t shy away from eating the nuts raw. If the stringy pith is peeled away as well as the shell, most of their bitterness will go. But roasting transforms them. They take on the sweetness and bulk of some tropical fruit. As is the case with so much else in this book, the excitement lies as much in the rituals of preparation as in the food itself. Chestnut roasting is an institution, rich with associations of smell, and of welcomingly hot coals in cold streets. To do it efficiently at home, slit the skins, and put the nuts in the hot ash of an open fire or close to the red coals – save one, which is put in uncut. When this explodes, the others are ready. The explosion is fairly ferocious, scattering hot shrapnel over the room, so sit well back from the fire and make sure all the other nuts have been slit.

© Bob Gibbons/FLPA

© ImageBroker/Imagebroker/FLPA, © Cisca Castelijns/FN/Minden/FLPA, © Cisca Castelijns/FN/Minden/FLPA, © David Hosking/FLPA

Chestnuts are highly versatile. They can be pickled, candied, or made into an amber with breadcrumbs and egg yolk. Boiled with Brussels sprouts they were Goethe’s favourite dish. Chopped, stewed and baked with red cabbage, they make a rich vegetable pudding.

Chestnut purée

Chestnut purée is a convenient form in which to use the nuts. Shell and peel the chestnuts. This is easily done if you boil them for 5 minutes first. Boil the shelled nuts again in a thin stock for about 40 minutes. Strain off the liquid and then rub the nuts through a sieve, or mash them in a liquidiser. The resulting purée can be seasoned and used as a substitute for potatoes, or it can form the basis of stuffings, soups and sweets, such as chestnut fool.

Chestnut and porcini soup

For 4 people

250 g (½ lb) chestnuts (tinned will do)

30 g (1 oz) dried porcini (better than fresh for this soup)

1 large onion

4 rashers of bacon

100 g (3½ oz) butter

lemon juice

fino sherry

• Peel the chestnuts, if you are using fresh ones, and boil for an hour in a large saucepan with just enough water to cover (40 minutes will do if you’re using vacuum-packed nuts).

• Reconstitute the dried porcini in sufficient boiling water to cover them, and leave to soak for 30 minutes. Hang on to the water.

• Meanwhile peel and finely slice the onion, cut the bacon rashers into broad slices, and fry both in the butter for about 10 minutes, until the onion is golden. Then slip this mixture, plus the porcini and their soaking water into the pan containing the chestnuts and their water. Simmer for a further 15 minutes.

• Cool the soup a little, and liquidise in batches until it’s thoroughly smooth, adding water if necessary until it is at your preferred consistency.

• Reheat in the pan with a squeeze of lemon juice, and just before serving add a small glass of fino sherry.

Chestnut flan

Chestnut flour is difficult to make at home, but is obtainable in most health food stores. This is a recipe from Corsica.

100 g (3½ oz) chestnut flour

750 ml (1½ pints) milk

150 g (5 oz) sugar

butter

4 eggs

Put the chestnut flour, milk and sugar into a saucepan and heat gently, stirring frequently until the flour lumps have vanished. Continue to simmer, just short of boiling until the mixture becomes quite thick (about 10 minutes). Line a round oven dish, about 5 cm deep, with greaseproof paper, and rub a little butter over the paper. Beat the eggs in a bowl, and stir into the chestnut mixture. Pour into the dish and bake in an oven at 160°C/gas 3 for 40 minutes. Leave to cool overnight., or for at least a few hours, and turn upside down on to a large plate before serving.

PS: Chestnut flour can be substituted for wheat flour in almost any recipe, provided you add baking powder to help it rise a little. Try it, for instance, in a Yorkshire pudding, cooked under the meat.

© Gary K Smith/FLPA

© Michael Krabs/Imagebroker/FLPA

© David Hosking/FLPA

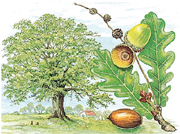

Oak OaQuercus robur/Quercus petraea

A common deciduous tree up to 35 m (115 ft) high, typically with a broad, domed crown. The two common species are pedunculate oak (Quercus robur), which occurs throughout Britain, and sessile oak (Q. petraea), which is the dominant species in northern and western Britain, and in Ireland. Leaves are distinctively shaped, with irregular lobes. The fruits (acorns) ripen in September to October.

The oak tree has formed part of our folklore and history for centuries, not only as a source of timber for building houses and ships but also as a source of food. Like beechmast, however, the chief economic use of acorns has been as animal fodder, and they have been used as human food chiefly in times of famine. The raw kernels are forbiddingly bitter to most palates, but chopped and roasted they can be used as a substitute for almonds. In Europe the most common use of acorns has been to roast them as a substitute for coffee, and they were recommended for this role during the Second World War. Chop the kernels, roast to a light brown colour, grind up, then roast again.

Hazel Corylus avellana

An abundant and widespread tree, found in woods, hedgerows and scrubland. A small tree or multi-stemmed shrub, 1.5–3.5 m (4–12 ft) high, with roundish, downy, toothed leaves. Well known for the yellow male catkins, called ‘lambs’ tails’, which appear in the winter. Nuts from late August to October, 1–2.5 cm (½–1 inch) long, ovoid and encased in a thick green-lobed husk.

The hazel was among the first species to recolonise the British Isles after the last Ice Age. It is an extremely useful tree, with leaves that can be used as food for livestock, branches for building fences and shelters, and nuts that can be eaten as food. Widely eaten in prehistoric times, the hazelnut became part of Celtic legend – its compact shape, hard shell and nutritious fruit was an emblem of concentrated wisdom. Today they are grown commercially in many parts of the world, and are second only to the almond as a world nut crop. Hazelnuts begin to ripen in mid-September, at about the same time that the leaves begin to yellow. You may have to compete with the birds and squirrels, as the nuts do not just provide a treat for humans. Look for them at the edges of woods and in mature hedges. Search inside bushes for the nuts, as well as working round them, and scan them with the sun behind you if possible. Use a walking stick to bend down the branches, and gather the nuts into a basket that stays open whilst you are picking: a plastic bag with one handle looped over your picking wrist is a useful device.

If the ground cover under the bush is relatively clear of grass, then it is worthwhile giving the bush a shake. Some of the invisible ripe nuts should find their way onto the ground after this. In fact it is always worth searching the ground underneath a hazel. If there are nuts there which are dark or grey-brown in colour then the kernels will have turned to dust. But there is a chance that there will also be fresh windfalls that have not yet been picked at by birds.

Once you have gathered the nuts, keep them in a dry, warm place but in their shells, so that the kernels don’t dry out as well. You can use the nuts chopped or grated in salads, or with apple, raisins and raw oatmeal (muesli). Ground up in a blender, mixed with milk and chilled, they make a passable imitation of the Spanish drink horchata (properly made from the roots of the nutsedge, Cyperus esculentus). But hazelnuts are such a rich food that it seems wasteful not to use them occasionally as a protein substitute. Weight for weight, they contain fifty per cent more protein, seven times more fat and five times more carbohydrate than hens’ eggs. What better way of cashing in on such a meaty hoard than the unjustly infamous nut cutlet?

© Marcus Webb/FLPA

© Robert Canis/FLPA

To make hazelnut bread, grind a cupful of young nuts, and mix with the same amount of self-raising flour, half a cup of sugar and a little salt. Beat an egg with milk, and add it to the mixture, beating then kneading it until you have a stiff dough. Mould to a loaf shape, and bake in a medium oven for 50 minutes. Hazel leaves were used in the fifteenth century to make ‘noteye’, a highly spiced pork stew. The leaves were ground and mixed with ginger, saffron, sugar, salt and vinegar, before being added to minced pork.

Nut cutlet

50 g (2 oz) oil

50 g (2 oz) flour

500 ml (1 pint) stock

75 g (3 oz) breadcrumbs

50 g (2 oz) grated hazelnuts

Milk or beaten egg for glazing

Salt and pepper

• Mix the oil and flour in a saucepan. Add the stock and simmer for ten minutes, stirring all the time.

• Add the breadcrumbs and grated hazelnuts. Season.

• Cool the mixture and shape into cutlets.

• Dip the cutlets into an egg and milk mixture, coat with breadcrumbs and fry in oil until brown.

© David Hosking/FLPA

Lime Tilia europaea

Common in parks, by roadsides and in ornamental woods and copses. The lime is a tall tree, up to 45 m (150 ft) when it is allowed to grow naturally, with a smooth, dark brown trunk usually interrupted by bosses and side shoots. Flowers in July, a drooping cluster of heavily scented yellow blossoms. Leaves are large and heart-shaped, smooth above, paler below with a few tufts of fine white hairs.

The common lime is a cultivated hybrid between the two species of native wild lime, small-leaved (Tilia cordata) and large-leaved (T. platyphyllos), and it is now much commoner than both. It is one of the most beneficent of trees: its branches are a favourite site for mistletoe; its inner bark, bast, was used for making twine; its pale, close-grained timber is ideal for carving; its fragrant flowers make one of the best honeys. Limes are remarkable for the fact that they can, in bloom, be tracked down by sound. In high summer their flowers are often so laden with bees that they can be heard 50 m (160 ft) away. The leaves make a useful salad vegetable. When young they are thick, cooling, and very glutinous. Before they begin to roughen, they make a sandwich filling, between thin slices of new bread, with unsalted butter and just a sprinkling of lemon juice. Cut off the stalks and wash well, but otherwise put them between the bread as they come off the tree. Some aficionados enjoy them when they are sticky with the honeydew produced by aphid invasions in the summer. In late June and July the yellow flowers of mature lime trees have a delicious honey-like fragrance, and make one of the very best teas of all wild flowers. It is popular in France, where it is sold under the name of tilleul.