Полная версия:

Food for Free

Omissions

This book covers the majority of wild plant food products which can be obtained in the British Isles. But there are some categories which I have deliberately omitted.

• There is nothing on grasses and cereals. This is intended to be a practical book, and no one is going to spend their time hand-gathering enough wild seeds to make flour.

• I have touched briefly on the traditional herbal uses of many plants where this is relevant or interesting. But I have included no plants purely on the grounds of their presumed therapeutic value. This is a book about food, not medicine.

• This is also a book about wild plant foods, which is the simple reason (apart from personal qualms) why there is nothing about fish and wildfowl.

• But I have included shellfish because, from a picker’s perspective, they are more like plants than animals. They stay more or less in one place, and are gathered, not caught.

Layout of the book

The text is divided into sections covering (1) edible plants (trees and herbaceous plants), (2) fungi, lichens and one fern, (3) seaweeds, (4) shellfish. Within each category, species are arranged in systematic order.

Some picking rules

I have given more detailed notes on gathering techniques in the introductions to the individual sections (particularly fungi, seaweeds and shellfish). But there are some general rules which apply to all wild food. Following these rules will help to guarantee the quality of what you are picking, and the health of the plant, fungus or shellfish population that is providing it.

Although we have tried to make both text and illustrations as helpful as possible in identifying the different plant products described in this book, they should not be regarded as a substitute for a comprehensive field guide. They will help you decide what to gather, but until you are experienced it is wise to double-check everything (particularly fungi) in a book devoted solely to identification. Conversely, never rely on illustrations alone as a guide to edibility. Some of the plants illustrated here need the special preparation described in the text before they are palatable.

But although it is obviously crucial to know what you are picking, don’t become obsessed about the possible dangers of poisoning. This is a natural worry when you are trying wild foods for the first time, but happily a groundless one. As you will see from the text there are relatively few common poisonous plants and fungi in Britain compared with the total number of plant species.

To put the dangers of wild foods into perspective it is worth considering the trials attendant on eating the cultivated foods we stuff into our mouths without question. Forgetting for a moment the perennial problems of additives and insecticide residues, and the new worries about irradiated and genetically modified food, how many people know that, in excess, cabbage can cause goitre and onions induce anaemia? That as little as one whole nutmeg can bring on days of hallucinations? Almost any food substance can occasionally bring on an allergic reaction in a susceptible subject, and oysters and strawberries, as well as nuts of all types, have particularly infamous reputations in this respect. But all these effects are rare. The point is that they are part of the hazards of eating itself, rather than of a particular category of food.

Here are some basic rules to ensure your safety when gathering and using wild foods:

• Make sure you correctly identify the plant, fungus or seaweed you are gathering.

• Do not gather any sort of produce from areas that may have been sprayed with insecticide or weedkiller.

• Avoid, too, the verges of heavily used roads, where the plant may have been contaminated by car exhausts. There are plenty of environments that are likely to be comparatively free of all types of contamination: commons, woods, the hedges along footpaths, etc. Even in a small garden you are likely to be able to find something like twenty of the species described in this book.

© David Hosking/FLPA

• Wherever possible use a flat open basket to gather your produce, to avoid squashing. If you are caught without a basket, and do not mind being folksy, pin together some dock or burdock leaves with thorns.

• When you have got the crop home, wash it well and sort out any old or decayed parts.

• To be doubly sure, it is as well to try fairly small portions of new foods the first time you eat them, just to ensure that you are not sensitive to them.

Having considered your own survival, consider the plant’s:

• Never strip a plant of leaves, berries, or whatever part you are picking. Take small quantities from each specimen, so that its appearance and health are not affected. It helps to use a knife or scissors (except with fungi).

• Never take the flowers or seeds of annual plants; they rely on them for survival.

• Do not take more than you need for your own needs.

• Be careful not to damage other vegetation or surrounding habitat when gathering wild food.

• Adhere at all times to the Code of Conduct for the conservation and enjoyment of wild plants, published by the Botanical Society of the British Isles (www.bsbi.org.uk/Code.htm).

What the law says

The law concerning foraging is comparatively straightforward, at least on the surface.

• You are allowed to gather and take away the four Fs – foliage, flowers, fruit, fungi – of clearly WILD plants, e.g. blackberries and elderflowers, even on private land, though other laws regarding trespass and criminal damage may restrict you. You are not entitled to harvest anything from CULTIVATED crop-plants, e.g orchard trees or field-peas.

• But under the Wildlife and Countryside Act and the Theft Act you may not SELL wild produce gathered in this way.

• Nor may you UPROOT any wild plant without the permission of the owner of the land on which it is growing.

• A few very RARE plants (none of those mentioned in this book) are protected by law from any kind of picking.

• On various areas of land otherwise open to the public – certain forests, commons, parks, and the new Open Access areas declared under the Countryside and Rights of Way Act, 2000 (CROW) – there are BY-LAWS prohibiting any kind of picking. These are usually spelt out on notice boards.

But there are cases which don’t fall into these clear extremes, about which the law is hazy. For example, nuts from a walnut tree overhanging a pavement are clearly the owner’s whilst they are on the tree. But how about those that have fallen onto the public right of way? And how, on a road embankment, can a planted apple-tree be distinguished from a self-sown wilding? In all such matters, and others where the law is ambiguous, use your common sense, and don’t be perpetually looking over your shoulder.

Edible plants

Roots

Roots are probably the least practical of all wild vegetables. Firstly, few species form thick, fleshy roots in the wild, and the coarse, wiry roots of – for instance – horse-radish and wild parsnip are really only suitable for flavouring. Second, under the Wildlife and Countryside Act it is illegal to dig up wild plants by the root, except on your own land, or with the permission of the landowner.

The few species that are subsequently recommended as roots are all very common and likely to crop up as garden weeds. Where palatable roots of a practical size and texture can be found, however, they are quite versatile, and may be used in the preparation of broths (herb-bennet), vegetable dishes (large-flowered evening-primrose), salads (oxeye daisy), or even drinks (chicory, dandelion).

Green vegetables

The main problem with wild leaf vegetables is their size. Not many wild plants have the big, floppy leaves for which cultivated greens have been bred, and as a result picking enough for a serving can be a long and irksome task. For this reason the optimum picking time for most leaf vegetables is probably their middle-age, when the flowers are out and the plant is easy to recognise, and the leaves have reached maximum size without beginning to wither.

Green vegetables can be roughly divided into three types: salads, cooked greens, and stems. For general recipes see dandelion for salads, sea beet or fat-hen for greens, and alexanders for stems.

All green vegetables can also be made into soup (see sorrel), blended into green sauces, or made into a pottage or ‘mess of greens’ by cooking a number of species together.

Herbs

A herb is generally defined as a leafy plant used not as a food in its own right but as a flavouring for other foods, and most herbs tend to be milder in the wild state than under domestication; being valued principally for their flavouring qualities, it is these which domestication has attempted to intensify, not delicacy, size, succulence or any of the other qualities that are sought after in staple vegetables. You will find, consequently, that with wild herbs you will need to double up the quantities you normally use of the cultivated variety.

The best time to pick a herb, especially for the purposes of drying, is just as it is coming into flower. This is the stage at which the plant’s nutrients and aromatic oils are still mainly concentrated in the leaves, yet it will have a few blossoms to assist with the identification. Gather your herbs in dry weather and preferably early in the morning before they have been exposed to too much sun. Wet herbs will tend to develop mildew during drying, and specimens picked after long exposure to strong sunshine will inevitably have lost some of their natural oils by evaporation.

Cut whole stalks of the herb with a knife or scissors to avoid damaging the parent plant. If you are going to use the herbs fresh, strip the leaves and flowers off the stalks as soon as you get them home. If you are going to dry them, leave the stalks intact as you have picked them. To maintain their colour and flavour they must be dried as quickly as possible but without too intense a heat. They therefore need a combination of gentle warmth and good ventilation. A kitchen or well-ventilated airing cupboard is ideal. The stalks can be hung up in loose bunches, or spread thinly on a sheet of paper and placed on the rack above the stove. Ideally, they should also be covered by muslin, to keep out flies and insects and, in the case of hanging bundles, to catch any leaves that start to crumble and fall as they dry. All herbs can be used to flavour vinegar, olive oil or drinks, as with thyme in aquavit.

Spices

Spices are the aromatic seeds of flowering plants. There are also a few roots (most notably horse-radish) that are generally regarded as spices.

Most plants which have aromatic leaves also have aromatic seeds, and can be usefully employed as flavourings. But a warning: do not expect the flavour of the two parts to be identical. They are often subtly different in ways that make it inadvisable simply to substitute seeds for leaves.

Seeds should always be allowed to dry on the plant. After flowering, annuals start to concentrate their food supplies into the seeds so that they have enough to survive through germination. This also, of course, increases the flavour and size of the seeds. When they are dry and ready to drop off the plant, their food content and flavour should be at a maximum.

Flowers

Gathering wild flowers for no other reason than their diverting flavours would at least be antisocial, and in the case of the rarest species it is illegal under the Wildlife and Countryside Act. Some of the flowers mentioned in this book are rare and should not be picked these days because of declining populations, though many of them have been anciently popular ingredients of salads, and are included for their historical interest.

The only species I advocate picking from are those where removing flowers in small quantities is unlikely to have much visual or biological effect. They are all common and hardy plants. They are all perennials and do not rely on seeding for continued survival. They are mostly bushes or shrubs in which each individual produces an abundant number of blossoms.

Most of the recipes in the book require no more than a handful or two of blossoms, but if you like the sound of any of them it may be best to grow the plants in your garden and pick the flowers there. Many species, such as cowslip and primrose, are commercially available as seed.

Fruits

A number of the fruits I have included are cultivated and used commercially as well as growing in the wild. Where this is the case I have not given much space to the more common kitchen uses, which can be found in any cookery book. I have concentrated instead on how to find and gather the wild varieties, and on the more unusual traditional recipes.

Almost all fruit, of course, can be used to make jellies and jams. Rather than repeat the relevant directions under each fruit, it is useful to go into some detail here. The notes below apply to all species.

Another process which can be applied to most of the harder-skinned fruits is drying. Choose slightly unripe fruit, wash well, and dry with a cloth. Then strew it out on a metal tray and place in a very low oven (50°C, 120°F). The fruit is dry when it yields no juice when squeezed between the fingers, but is not so far gone that it rattles. This usually takes between 4 and 6 hours.

Most of the fruits in this section can also be used to make wine (not covered in this book); fruit liqueurs (see, for example, sloe gin); flavoured vinegars (see raspberry); pies, fools (see gooseberry); summer or autumn puddings (see raspberry, and blackberry).

Some fruits, notably the medlar and the fruit of the service-tree, need to be ‘bletted’ – in other words, half-rotten – before they are edible.

Making a jelly

Jellies and jams form because of a chemical reaction between a substance called pectin, present in the fruit, and sugar. The pectin (and the fruit’s acids, which also play a part in the reaction) tend to be most concentrated when the fruit is under-ripe. But then of course the flavour is only partly developed. So the optimum time for picking fruit for jelly is when it is just ripe.

The amount of pectin available varies from fruit to fruit. Apples, gooseberries and currants, for instance, are rich in pectin and acid and set very readily. Blackberries and strawberries, on the other hand, have a low pectin content, and usually need to have some added from an outside source before they will form a jelly. Lemon juice or sour crab apples are commonly used for this.

The first stage in making a jelly is to pulp the fruit. Do this by packing the clean fruit into a saucepan or preserving pan and just covering with water. Bring to the boil and simmer until all the fruit is mushy. With the harderskinned fruits (rosehips, haws, etc.) you may need to help the process along by pressing with a spoon, and be prepared to simmer for up to half an hour. This is the stage to supplement the pectin, if your fruit has poor setting properties. Add the juice of one lemon for every 900 g (2 lb) of fruit.

When you have your pulp, separate the juice from the roughage and fibres by straining through muslin. This can be done by lining a large bowl with a good-sized sheet of muslin, folded at least double, and filling the bowl with the fruit pulp. Then lift and tie the corners of the muslin, using the back of a chair or a low clothes line as the support, so that it hangs like a sock above the bowl. Alternatively, use a real stocking, or a purpose-made straining bag.

To obtain the maximum volume of juice, allow the pulp to strain overnight. It is not too serious to squeeze the muslin if you are in a hurry, but it will force some of the solid matter through and affect the clarity of the jelly. When you have all the juice you want, measure its volume, and transfer it to a clean saucepan, adding 500 g (1 lb) of sugar for every 500 ml (1 pint) of juice. Bring to the boil, stirring well, and boil rapidly, skimming off any scum that floats to the surface. A jelly will normally form when the mixture has reached a temperature of 105°C (221°F) on a jam thermometer. If you have no thermometer, or want a confirmatory test, transfer one drop of the mixture with a spoon onto a cold saucer. If setting is imminent, the drop will not run after a few seconds because of a skin – often visible – formed across it.

As soon as the setting temperature has been achieved, pour the mixture into some clear, warm jars (preferably standing on a metal surface to conduct away some of the heat). Cover the surface of the jelly with a wax disc, wax side down. Add a cellophane cover, moistening it on the outside first so that it dries taut. Hold the cover in place with a rubber band, label the jar clearly, and store in a cool place.

Nuts

The majority of plants covered by this book are in the ‘fruit and veg’ category. They make perfectly acceptable accompaniments or conclusions to a meal, but would leave you feeling a little peckish if you relied on nothing else. Nuts are an exception. They are the major source of second-class protein amongst wild plants. Walnuts, for instance, contain 18 per cent protein, 60 per cent fat, and can provide over 600 kilocalories per 100 grams of kernels.

It is therefore possible to substitute nuts for the more conventional protein constituents of a meal, as indeed vegetarians have been doing for centuries. But do not pick them to excess because of this. Wild nuts are crucial to the survival of many wild birds and animals, who have just as much right to them, and considerably more need.

Keep those you do pick very dry, for damp and mould can easily permeate nutshells and rot the kernel. As well as being edible in their natural state, nuts may be eaten pickled or puréed, mixed into salads, or as a main constituent of vegetable dishes.

© Robin Chittenden/FLPA

© Horst Sollinger/Imagebroker/FLPA

Trees

Scots Pine

Juniper

Barberry

Hop

Walnut

Beech

Sweet Chestnut

Oak

Hazel

Lime

Sloe, Blackthorn

Wild Cherry

Bullace, Damsons and Wild Plums

Crab Apple

Rowan, Mountain-ash

Wild Service-tree

Whitebeam

Juneberry

Medlar

Hawthorn, May-tree

Elder

Oregon-grape

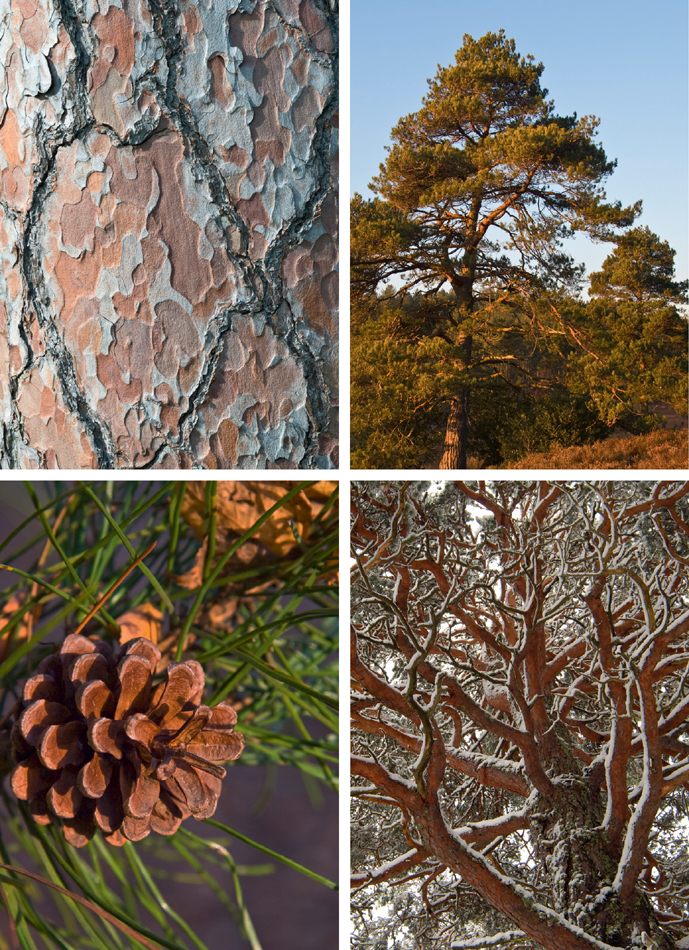

Scots Pine Pinus sylvestris

A conical evergreen when young and growing vigorously, up to 36 m (118 ft), becoming much more open, and flat-topped with a long bole, when older. Red- or grey-brown bark low down on the trunk, but markedly red or orange higher up in mature trees. Irregular branches, with needles in bunches of two, grey-green or blue-green, up to 7 cm (2½ inches) long. Native to Scotland, and originally much of Britain, as well as much of Europe and Asia.

A winemaker with patience and ingenuity might be able to devise a way of making a kind of retsina by steeping in a white wine base the resin that oozes from the bark of the Scots pine. But it is the needles that are the principal food interest of this tree, because of their strong and refreshing fragrance.

The Scots pine is our only truly indigenous pine, native in parts of Scotland and widely planted and naturalised elsewhere. The needles are quite distinctive, being much shorter than those of other species of pine, grey-green in colour and arranged in rather twisted pairs along the twigs. But the needles of any type of pine will do for cooking, provided they are gathered when fairly young, between April and August.

Anyone who has the patience to extract the tiny nuts from the pine cones will find this nail-breaking work rewarded by a pleasant wayside snack. (The pine nuts used in cookery come from the Mediterranean stone pine, pinus pinea.)

Pine needle tea

Tea made from pine needles is a favourite American wild food beverage, though it has a decidedly medicinal taste. Take about 2 tablespoons of fresh needles, and steep in a cup of hot water for about 5 minutes. Strain and add honey and lemon juice to taste.

Pine needle oil

A recipe for an aromatic oil which makes good use of pine needles’ strong resinous scent simply involves soaking the needles in olive oil for a week or two; the resultant oil is superb for making into French dressings or for cooking meat in.

© Krystyna Szulecka/FLPA, © Nicholas and Sherry Lu Aldridge/FLPA, © Nicholas and Sherry Lu Aldridge/FLPA, © Andrew Parkinson/FLPA

© Fred Hazelhoff/FN/Minden/FLPA

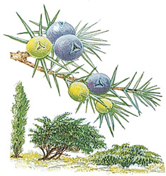

Juniper Juniperus communis

Locally common on chalk downs, limestone hills, heaths and moors, chiefly in southeast England and the north. A shrub 1.5–3.5 m (4–12 ft) high – though there is also a prostrate form – with whorls of narrow evergreen leaves. Flowers, small, yellow, at the base of the leaves, appear in May and June. The fruit is a green berry-like cone, appearing in June but not ripening until September or October of its second year, when it turns blue-black.

At the time of ripening, juniper berries are rich in oil, which is the source of their use as a flavouring. They are of course best known as the flavouring in gin, and most of the historical uses have been in one kind of drink or another (though home-grown berries have not been used by British distillers for over a century). Experiment with drinks in which the berries have been steeped. Even gin is improved by, as it were, a double dose.

Uses across Europe are varied. The berries have been roasted and ground as a coffee substitute. In Sweden they are used to make a type of beer, and are often turned into jam. In France, genevrette is made by fermenting a mixture of juniper berries and barley.

Crushed juniper berries are becoming increasingly popular as a flavouring for white meat or game dishes. In Belgium they are used to make a sauce for pork chops. Seal the chops on both sides and place in a shallow casserole. Sprinkle with lemon juice and add parsley, four crushed juniper berries, rosemary, salt and pepper. Arrange peeled and sliced apples over the top and then pour over melted butter. Cook in a medium oven for 30 minutes.

Barberry Berberis vulgaris

A shrub of hedge and waste places, growing to 3 m (10 ft). It is spiny, with small, toothed oval leaves, yellow flowers and scarlet berries from July.

Because of its spiny branches and brilliant scarlet berries, barberry was once popular as a hedging plant. It was stockproof as well as being ornamental. Then, last century, it was discovered that the foliage was a host of the black rust fungus that could devastate cereal crops, and most bushes growing near arable fields were destroyed. Today barberry is largely confined to hedges in pastureland and to old parks and commons. The berries are strikingly attractive, being brilliant red in colour, oblong in shape and hung in loose clusters all over the bushes. They are usually ready by late August or early September, but check their ripeness by seeing if a berry will burst when squeezed. It is advisable to use scissors and gloves when picking because of the shrub’s long, sharp spines.