Полная версия

Полная версияThe Life of Friedrich Schiller

'I answered, that perhaps the initiated themselves were never rightly at their ease in it, and that there surely was another way of representing Nature, not separated and disunited, but active and alive, and expanding from the whole into the parts. On this point he requested explanations, but did not hide his doubts; he would not allow that such a mode, as I was recommending, had been already pointed out by experiment.

'We reached his house; the talk induced me to go in. I then expounded to him with as much vivacity as possible, the Metamorphosis of Plants,71 drawing out on paper, with many characteristic strokes, a symbolic Plant for him, as I proceeded. He heard and saw all this with much interest and distinct comprehension; but when I had done, he shook his head and said: "This is no experiment, this is an idea." I stopped with some degree of irritation; for the point which separated us was most luminously marked by this expression. The opinions in Dignity and Grace again occurred to me; the old grudge was just awakening; but I smothered it, and merely said: "I was happy to find that I had got ideas without knowing it, nay that I saw them before my eyes."

'Schiller had much more prudence and dexterity of management than I: he was also thinking of his periodical the Horen, about this time, and of course rather wished to attract than repel me. Accordingly he answered me like an accomplished Kantite; and as my stiff necked Realism gave occasion to many contradictions, much battling took place between us, and at last a truce, in which neither party would consent to yield the victory, but each held himself invincible. Positions like the following grieved me to the very soul: How can there ever be an experiment that shall correspond with an idea? The specific quality of an idea is, that no experiment can reach it or agree with it. Yet if he held as an idea the same thing which I looked upon as an experiment, there must certainly, I thought, be some community between us, some ground whereon both of us might meet! The first step was now taken; Schiller's attractive power was great, he held all firmly to him that came within his reach: I expressed an interest in his purposes, and promised to give out in the Horen many notions that were lying in my head; his wife, whom I had loved and valued since her childhood, did her part to strengthen our reciprocal intelligence; all friends on both sides rejoiced in it; and thus by means of that mighty and interminable controversy between object and subject, we two concluded an alliance, which remained unbroken, and produced much benefit to ourselves and others.'

The friendship of Schiller and Goethe forms so delightful a chapter in their history, that we long for more and more details respecting it. Sincerity, true estimation of each other's merit, true sympathy in each other's character and purposes appear to have formed the basis of it, and maintained it unimpaired to the end. Goethe, we are told, was minute and sedulous in his attention to Schiller, whom he venerated as a good man and sympathised with as an afflicted one: when in mixed companies together, he constantly endeavoured to draw out the stores of his modest and retiring friend; or to guard his sick and sensitive mind from annoyances that might have irritated him; now softening, now exciting conversation, guiding it with the address of a gifted and polished man, or lashing out of it with the scorpion-whip of his satire much that would have vexed the more soft and simple spirit of the valetudinarian. These are things which it is good to think of: it is good to know that there are literary men, who have other principles besides vanity; who can divide the approbation of their fellow mortals, without quarrelling over the lots; who in their solicitude about their 'fame' do not forget the common charities of nature, in exchange for which the 'fame' of most authors were but a poor bargain.

NO. 4. PAGE 125.

DEATH OF GUSTAVUS ADOLPHUS

As a specimen of Schiller's historical style, we have extracted a few scenes from his masterly description of the Battle of Lützen. The whole forms a picture, executed in the spirit of Salvator; and though this is but a fragment, the importance of the figure represented in it will perhaps counterbalance that deficiency.

'At last the dreaded morning dawned; but a thick fog, which lay brooding over all the field, delayed the attack till noon. Kneeling in front of his lines, the King offered up his devotions; the whole army, at the same moment, dropping on their right knees, uplifted a moving hymn, and the field-music accompanied their singing. The King then mounted his horse; dressed in a jerkin of buff, with a surtout (for a late wound hindered him from wearing armour), he rode through the ranks, rousing the courage of his troops to a cheerful confidence, which his own forecasting bosom contradicted. God with us was the battle-word of the Swedes; that of the Imperialists was Jesus Maria. About eleven o'clock, the fog began to break, and Wallenstein's lines became visible. At the same time, too, were seen the flames of Lützen, which the Duke had ordered to be set on fire, that he might not be outflanked on this side. At length the signal pealed; the horse dashed forward on the enemy; the infantry advanced against his trenches.

'Meanwhile the right wing, led on by the King in person, had fallen on the left wing of the Friedlanders. The first strong onset of the heavy Finland Cuirassiers scattered the light-mounted Poles and Croats, who were stationed here, and their tumultuous flight spread fear and disorder over the rest of the cavalry. At this moment notice reached the King that his infantry were losing ground, and likely to be driven back from the trenches they had stormed; and also that his left, exposed to a tremendous fire from the Windmills behind Lützen, could no longer keep their place. With quick decision, he committed to Von Horn the task of pursuing the already beaten left wing of the enemy; and himself hastened, at the head of Steinbock's regiment, to restore the confusion of his own. His gallant horse bore him over the trenches with the speed of lightning; but the squadrons that came after him could not pass so rapidly; and none but a few horsemen, among whom Franz Albert, Duke of Sachsen-Lauenburg, is mentioned, were alert enough to keep beside him. He galloped right to the place where his infantry was most oppressed; and while looking round to spy out some weak point, on which his attack might be directed, his short-sightedness led him too near the enemy's lines. An Imperial sergeant (gefreiter), observing that every one respectfully made room for the advancing horseman, ordered a musketeer to fire on him. "Aim at him there," cried he; "that must be a man of consequence." The soldier drew his trigger; and the King's left arm was shattered by the ball. At this instant, his cavalry came galloping up, and a confused cry of "The King bleeds! The King is shot!" spread horror and dismay through their ranks. "It is nothing: follow me!" exclaimed the King, collecting all his strength; but overcome with pain, and on the point of fainting, he desired the Duke of Lauenburg, in French, to take him without notice from the tumult. The Duke then turned with him to the right wing, making a wide circuit to conceal this accident from the desponding infantry; but as they rode along, the King received a second bullet through the back, which took from him the last remainder of his strength. "I have got enough, brother," said he with a dying voice: "haste, save thyself." With these words he sank from his horse; and here, struck by several other bullets, far from his attendants, he breathed out his life beneath the plundering hands of a troop of Croats. His horse flying on without its rider, and bathed in blood, soon announced to the Swedish cavalry the fall of their King; with wild yells they rush to the spot, to snatch that sacred spoil from the enemy. A deadly fight ensues around the corpse, and the mangled remains are buried under a hill of slain men.

'The dreadful tidings hasten in a few minutes over all the Swedish army: but instead of deadening the courage of these hardy troops, they rouse it to a fierce consuming fire. Life falls in value, since the holiest of all lives is gone; and death has now no terror for the lowly, since it has not spared the anointed head. With the grim fury of lions, the Upland, Smäland, Finnish, East and West Gothland regiments dash a second time upon the left wing of the enemy, which, already making but a feeble opposition to Von Horn, is now utterly driven from the field.

'But how dear a victory, how sad a triumph! Now first when the rage of battle has grown cold, do they feel the whole greatness of their loss, and the shout of the conqueror dies in a mute and gloomy despair. He who led them on to battle has not returned with them. Apart he lies, in his victorious field, confounded with the common heaps of humble dead. After long fruitless searching, they found the royal corpse, not far from the great stone, which had already stood for centuries between Lützen and the Merseburg Canal, but which, ever since this memorable incident, has borne the name of Schwedenstein, the Stone of the Swede. Defaced with wounds and blood, so as scarcely to be recognised, trodden under the hoofs of horses, stripped of his ornaments, even of his clothes, he is drawn from beneath a heap of dead bodies, brought to Weissenfels, and there delivered to the lamentations of his troops and the last embraces of his Queen. Vengeance had first required its tribute, and blood must flow as an offering to the Monarch; now Love assumes its rights, and mild tears are shed for the Man. Individual grief is lost in the universal sorrow. Astounded by this overwhelming stroke, the generals in blank despondency stand round his bier, and none yet ventures to conceive the full extent of his loss.'

The descriptive powers of the Historian, though the most popular, are among the lowest of his endowments. That Schiller was not wanting in the nobler requisites of his art, might he proved from his reflections on this very incident, 'striking like a hand from the clouds into the calculated horologe of men's affairs, and directing the considerate mind to a higher plan of things.' But the limits of our Work are already reached. Of Schiller's histories and dramas we can give no farther specimens: of his lyrical, didactic, moral poems we must take our leave without giving any. Perhaps the time may come, when all his writings, transplanted to our own soil, may be offered in their entire dimensions to the thinkers of these Islands; a conquest by which our literature, rich as it is, might be enriched still farther.

APPENDIX II

APPENDIX II

The preceding Appendix, which is here marked "Appendix First," has hitherto, in all Editions, been the only one, and has ended the Book. As indeed, for the common run of English readers, it still essentially may, or even must. But now, for a more select class, and on inducements that are accidental and peculiar, there is, in this final or farewell Edition, which stands without change otherwise, something to be added as Appendix Second, by the opportunity that offers.

Schiller has now many readers of his own in England: perhaps the most and best that read this my poor Account of his Life know something of Germany and him at first-hand; and have their curiosity awake in regard to things German:—to such readers, if not to others, I can expect that the following Reprint or Reproduction of a Piece from the greatest of Germans, which connects itself with Schiller and this Book on Schiller, may not be unwelcome. To myself it has become symbolical, touching and memorable; and much invites my insertion of it here, since there happens to be room.

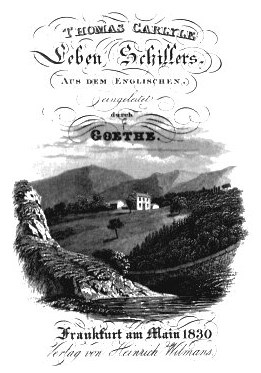

Certainly an interesting little circumstance in the history of this Book, and to me the one circumstance that now has any interest, is, That a German Translation of it had the altogether unexpected honour of an Introductory Preface by Goethe, in the last years of his life. A beautiful small event to me and mine, in our then remote circle; coming suddenly upon us, like a little outbreak of sunshine and azure, in the common gray element there! It was one of the more salient points of a certain individual relation, and far-off personal intercourse, which had arisen some years before, with the great man whom we had never seen, and never saw; and which was very beautiful, high, singular and dear to us,—to myself, and to Another who is not with me now. A little gleam as of celestial radiancy, miraculous almost, but indisputable, shining out on us always from time to time; somewhat ennobling for us the much of impediment that lay there, and forbidding it altogether to impede. Truly there are few things I now remember with a more bright or pious feeling than our then relation, amid the Scottish moors, to the man whom of all others I the most honoured, and felt that I was the most indebted to. Looking back on all this, through the vista of almost forty years, and what they have brought and have taken, I decide to reproduce this Goethe Introduction, as a little pillar of memorial, while time yet is.

Many of my present readers, too, readers especially of this Volume, may have their curiosities about the "Introduction (Einleitung)" of so small a thing by so great a man (which withal is a Piece not to be found in the great man's Collected Works, or elsewhere that I know of):—and will good-naturedly allow me to have my own way with it, namely to reprint it here in the original words. And will not even quarrel with me if I reproduce in facsimile those poor "Verzierungen (Copperplates)" of Goethe's devising, Shadows of Human Dwellings far away; judging well how beautiful and full of meaning the poorest of them now is to me.

Subjoined, on the next page, is Goethe's List or 'special Indication' of these latter; the only words of his which, on this occasion, I translate as well (Note of 1868):

'Special Indication of the Localities represented

'Frontispiece, Thomas Carlyle's House in the County of Dumfries, South of Scotland.

'Titlepage Vignette, The Same in the distance.

'Upper-side of Cover, Schiller's House in Weimar.

'Under-side of Cover, Solitary small Apartment in Schiller's Garden, over the Leutra Brook in Jena, built by himself; where, in the completest seclusion, he wrote many things, Maria Stuart in particular. After his removal from Jena, and subsequent decease, the little Edifice was taken away as threatening to fall ruinous; and we wished here to preserve the remembrance of it.'

Nähere Bezeichnung der dargestellten Lokalitäten

Titelkupfer, Thomas Carlyles Wohnung in der Graffschaft Dumfries, des südlichen Schottlands.

Titel-Vignette, dieselbe in der Ferne.

Vorderseite des Umschlags, Wohnung Schillers in Weimar.

Rückseite des Umschlags, einsames Häuschen in Schillers Garten, über der Jenaischen Leutra, von ihm selbst errichtet; wo er in vollkommenster Einsamkeit manches, besonders Maria Stuart schrieb. Nach seiner Entfernung und erfolgtem Scheiden, trug man es ab, wegen Wandelbarkeit, und man gedachte hier das Andenken desselben zu erhalten.

Frankfurt am Main, 1830Verlag von Heinrich Wilmans

Der hochansehnlichenGesellschaftfür ausländischeschöne Literatur,zuBerlin

Als gegen Ende des vergangenen Jahres ich die angenehme Nachricht erhielt, dass eine mir freundlich bekannte Gesellschaft, welche bisher ihre Aufmerksamkeit inländischer Literatur gewidmet hatte, nunmehr dieselbe auf die ausländische zu wenden gedenke, konnte ich in meiner damaligen Lage nicht ausführlich und gründlich genug darlegen, wie sehr ich ein Unternehmen, bey welchen man auch meiner auf das geneigteste gedacht hatte, zu schätzen wisse.

Selbst mit gegenwärtigem öffentlichen Ausdruck meines dankbaren Antheils geschieht nur fragmentarisch was ich im bessern Zusammenhang zu überliefern gewünscht hätte. Ich will aber auch das wie es mir vorliegt nicht zurückweisen, indem ich meinen Hauptzweck dadurch zu erreichen hoffe, dass ich nämlich meine Freunde mit einem Manne in Berührung bringe, welchen ich unter diejenigen zähle, die in späteren Jahren sich an mich thätig angeschlossen, mich durch eine mitschreitende Theilnahme zum Handeln und Wirken aufgemuntert, und durch ein edles, reines wohlgerichtetes Bestreben wieder selbst verjüngt, mich, der ich sie heranzog, mit sich fortgezogen haben. Es ist der Verfasser des hier übersetzten Werkes, Herr Thomas Carlyle, ein Schotte, von dessen Thätigkeit und Vorzügen, so wie von dessen näheren Zuständen nachstehende Blätter ein Mehreres eröffnen werden.

Wie ich denselben und meine Berliner Freunde zu kennen glaube, so wird zwischen ihnen und ihm eine frohe wirksame Verbindung sich einleiten und beide Theile werden, wie ich hoffen darf, in einer Reihe von Jahren sich dieses Vermächtnisses und seines fruchtbaren Erfolges zusammen erfreuen, so dass ich ein fortdauerndes Andenken, um welches ich hier schliesslich bitten möchte, schon als dauernd gegönnt, mit anmuthigen Empfindungen voraus geniessen kann.

in treuer Anhänglichkeit und Theilnahme.

Weimar April

1830.

J. W. v. Goethe.Es ist schon einige Zeit von einer allgemeinen Weltliteratur die Rede und zwar nicht mit Unrecht: denn die sämmtlichen Nationen, in den fürchterlichsten Kriegen durcheinander geschüttelt, sodann wieder auf sich selbst einzeln zurückgeführt, hatten zu bemerken, dass sie manches Fremde gewahr worden, in sich aufgenommen, bisher unbekannte geistige Bedürfnisse hie und da empfunden. Daraus entstand das Gefühl nachbarlicher Verhältnisse, und anstatt dass man sich bisher zugeschlossen hatte, kam der Geist nach und nach zu dem Verlangen, auch in den mehr oder weniger freyen geistigen Handelsverkehr mit aufgenommen zu werden.

Diese Bewegung währt zwar erst eine kurze Weile, aber doch immer lang genug, um schon einige Betrachtungen darüber anzustellen, und aus ihr bald möglichst, wie man es im Waarenhandel ja auch thun muss, Vortheil und Genuss zu gewinnen.

Gegenwärtiges, zum Andenken Schillers, geschriebene Werk kann, übersetzt, für uns kaum etwas Neues bringen; der Verfasser nahm seine Kenntnisse aus Schriften, die uns längst bekannt sind, so wie denn auch überhaupt die hier verhandelten Angelegenheiten bey uns öfters durchgesprochen und durchgefochten worden.

Was aber den Verehrern Schillers, und also einem jeden Deutschen, wie man kühnlich sagen darf, höchst erfreulich seyn muss, ist: unmittelbar zu erfahren, wie ein zartfühlender, strebsamer, einsichtiger Mann über dem Meere, in seinen besten Jahren, durch Schillers Productionen berührt, bewegt, erregt und nun zum weitern Studium der deutschen Literatur angetrieben worden.

Mir wenigstens war es rührend, zu sehen, wie dieser, rein und ruhig denkende Fremde, selbst in jenen ersten, oft harten, fast rohen Productionen unsres verewigten Freundes, immer den edlen, wohldenkenden, wohlwollenden Mann gewahr ward und sich ein Ideal des vortrefflichsten Sterblichen an ihm auferbauen konnte.

Ich halte deshalb dafür dass dieses Werk, als von einem Jüngling geschrieben, der deutschen Jugend zu empfehlen seyn möchte: denn wenn ein munteres Lebensalter einen Wunsch haben darf und soll, so ist es der: in allem Geleisteten das Löbliche, Gute, Bildsame, Hochstrebende, genug das Ideelle, und selbst in dem nicht Musterhaften, das allgemeine Musterbild der Menschheit zu erblicken.

Ferner kann uns dieses Werk von Bedeutung seyn, wenn wir ernstlich betrachten: wie ein fremder Mann die Schillerischen Werke, denen wir so mannigfaltige Kultur verdanken, auch als Quelle der seinigen schätzt, verehrt und dies, ohne irgend eine Absicht, rein und ruhig zu erkennen giebt.

Eine Bemerkung möchte sodann hier wohl am Platze seyn: dass sogar dasjenige, was unter uns beynahe ausgewirkt hat, nun, gerade in dem Augenblicke welcher auswärts der deutschen Literatur günstig ist, abermals seine kräftige Wirkung beginne und dadurch zeige, wie es auf einer gewissen Stufe der Literatur immer nützlich und wirksam seyn werde.

So sind z. B. Herders Ideen bey uns dergestalt in die Kenntnisse der ganzen Masse übergegangen, dass nur wenige, die sie lesen, dadurch erst belehrt werden, weil sie, durch hundertfache Ableitungen, von demjenigen was damals von grosser Bedeutung war, in anderem Zusammenhange schon völlig unterrichtet worden. Dieses Werk ist vor kurzem ins Französische übersetzt; wohl in keiner andern Ueberzeugung als dass tausend gebildete Menschen in Frankreich sich immer noch an diesen Ideen zu erbauen haben.

In Bezug auf das dem gegenwärtigen Bande vorgesetzte Bild sey folgendes gemeldet: Unser Freund, als wir mit ihm in Verhältniss traten, war damals in Edinburgh wohnhaft, wo er in der Stille lebend, sich im besten Sinne auszubilden suchte, und, wir dürfen es ohne Ruhmredigkeit sagen, in der deutschen Literatur hiezu die meiste Förderniss fand.

Später, um sich selbst und seinen redlichen literarischen Studien unabhängig zu leben, begab er sich, etwa zehen deutsche Meilen südlicher, ein eignes Besitzthum zu bewohnen und zu benutzen, in die Grafschaft Dumfries. Hier, in einer gebirgigen Gegend, in welcher der Fluss Nithe dem nahen Meere zuströmt, ohnfern der Stadt Dumfries, an einer Stelle welche Craigenputtock genannt wird, schlug er mit einer schönen und höchst gebildeten Lebensgefährtin seine ländlich einfache Wohnung auf, wovon treue Nachbildungen eigentlich die Veranlassung zu gegenwärtigem Vorworte gegeben haben.

Gebildete Geister, zartfühlende Gemüther, welche nach fernem Guten sich bestreben, in die Ferne Gutes zu wirken geneigt sind, erwehren sich kaum des Wunsches, von geehrten, geliebten, weitabgesonderten Personen das Portrait, sodann die Abbildung ihrer Wohnung, so wie der nächsten Zustände, sich vor Augen gebracht zu sehen.

Wie oft wiederholt man noch heutiges Tags die Abbildung von Petrarch's Aufenthalt in Vaucluse, Tasso's Wohnung in Sorent! Und ist nicht immer die Bieler Insel, der Schutzort Rousseau's, ein seinen Verehrern nie genugsam dargestelltes Local?

In eben diesem Sinne hab' ich mir die Umgebungen meiner entfernten Freunde im Bilde zu verschaffen gesucht, und ich war um so mehr auf die Wohnung Hrn. Thomas Carlyle begierig, als er seinen Aufenthalt in einer fast rauhen Gebirgsgegend unter dem 55ten Grade gewählt hatte.

Ich glaube durch solch eine treue Nachbildung der neulich eingesendeten Originalzeichnungen gegenwärtiges Buch zu zieren und dem jetzigen gefühlvollen Leser, vielleicht noch mehr dem künftigen, einen freundlichen Gefallen zu erweisen und dadurch, so wie durch eingeschaltete Auszüge aus den Briefen des werthen Mannes, das Interesse an einer edlen allgemeinen Länder- und Weltannäherung zu vermehren.

Thomas Carlyle an GoetheCraigenputtock den 25. Septbr. 1828.

"Sie forschen mit so warmer Neigung nach unserem gegenwärtigen Aufenthalt und Beschäftigung, dass ich einige Worte hierüber sagen muss, da noch Raum dazu übrig bleibt. Dumfries ist eine artige Stadt, mit etwa 15000 Einwohnern und als Mittelpunct des Handels und der Gerichtsbarkeit anzusehen eines bedeutenden Districkts in dem schottischen Geschäftskreis. Unser Wohnort ist nicht darin, sondern 15 Meilen (zwei Stunden zu reiten) nordwestlich davon entfernt, zwischen den Granitgebirgen und dem schwarzen Moorgefilde, welche sich westwärts durch Gallovay meist bis an die irische See ziehen. In dieser Wüste von Heide und Felsen stellt unser Besitzthum eine grüne Oase vor, einen Raum von geackertem, theilweise umzäumten und geschmückten Boden, wo Korn reift und Bäume Schatten gewähren, obgleich ringsumher von Seemöven und hartwolligen Schaafen umgeben. Hier, mit nicht geringer Anstrengung, haben wir für uns eine reine, dauerhafte Wohnung erbaut und eingerichtet; hier wohnen wir in Ermangelung einer Lehr- oder andern öffentlichen Stelle, um uns der Literatur zu befleissigen, nach eigenen Kräften uns damit zu beschäftigen. Wir wünschen dass unsre Rosen und Gartenbüsche fröhlich heranwachsen, hoffen Gesundheit und eine friedliche Gemüthsstimmung, um uns zu fordern. Die Rosen sind freylich zum Theil noch zu pflanzen, aber sie blühen doch schon in Hoffnung.