Полная версия

Полная версияThe Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries

"When the travels of Marco Polo first appeared, they were generally regarded as fiction; and as this absurd belief had so far gained ground, that when he lay upon his death bed, his friends and nearest relatives, coming to take their eternal adieu, conjured him as he valued the salvation of his soul, to retract whatever he had advanced in his book, or at least many such passages as every person looked upon as untrue; but the traveler whose conscience was untouched upon that score, declared solemnly, in that awful moment, that far from being guilty of exaggeration, he had not described one-half of the wonderful things which he had beheld. Such was the reception which the discoveries of this extraordinary man experienced when first promulgated. By degrees, however, as enterprise lifted more and more the veil from Central and Eastern Asia the relations of our traveler rose in the estimation of geographers; and now that the world—though containing many unknown tracts—has been more successfully explored, we begin to perceive that Marco Polo, like Herodotus, was a man of the most rigid veracity, whose testimony presumptuous ignorance alone can call in question."

There is many a fable that clings around the name of Marco Polo, but this distinguished traveler needs no fictitious adornments of his tale to make him one of the greatest explorers of all time. It is sometimes said that he helped to introduce many important inventions into Europe and one even finds his name connected with the mariner's compass and with gunpowder. There are probably no good grounds for thinking that Europe owes any knowledge of either of these great inventions to the Venetian traveler. With regard to printing there is more doubt and Polo's passage with regard to movable blocks for printing paper money as used in China may have proved suggestive.

There is no need, however, of surmises in order to increase his fame for the simple story of his travels is quite sufficient for his reputation for all time. As has been well said most of the modern travelers and explorers have only been developing what Polo indicated at least in outline, and they have been scarcely more than describing with more precision of detail what he first touched upon and brought to general notice. When it is remembered that he visited such cities in Eastern Turkestan as Kashgar, Yarkand, and Khotan, which have been the subject of much curiosity only satisfied in quite recent years, that he had visited Thibet, or at least had traveled along its frontier, that to him the medieval world owed some definite knowledge of the Christian kingdom of Abyssinia and all that it was to know of China for centuries almost, his merits will be readily appreciated. As a matter of fact there was scarcely an interesting country of the East of which Marco Polo did not have something to relate from his personal experiences. He told of Burmah, of Siam, of Cochin China, of Japan, of Java, of Sumatra, and of other islands of the great Archipelago, of Ceylon, and of India, and all of these not in the fabulous dreamland spirit of one who has not been in contact with the East but in very definite and precise fashion. Nor was this all. He had heard and could tell much, though his geographical lore was legendary and rather dim, of the Coast of Zanzibar, of the vast and distant Madagascar, and in the remotely opposite direction of Siberia, of the shores of the Arctic Ocean, and of the curious customs of the inhabitants of these distant countries.

How wonderfully acute and yet how thoroughly practical some of Polo's observations were can be best appreciated by some quotations from his description of products and industries as he saw them on his travels. We are apt to think of the use of petroleum as dating from much later than the Thirteenth Century, but Marco Polo had not only seen it in the Near East on his travels, but evidently had learned much of the great rock-oil deposits at Baku which constitute the basis for the important Russian petroleum industry in modern times. He says:

"On the north (of Armenia) is found a fountain from which a liquor like oil flows, which, though unprofitable for the seasoning of meat, is good for burning and for anointing camels afflicted with the mange. This oil flows constantly and copiously, so that camels are laden with it."

He is quite as definite in the information acquired with regard, to the use of coal. He knew and states very confidently that there were immense deposits of coal in China, deposits which are so extensive that distinguished geologists and mineralogists who have learned of them in modern times have predicted that eventually the world's great manufacturing industries would be transferred to China. We are apt to think that this mineral wealth is not exploited by the Chinese, yet even in Marco Polo's time, as one commentator has remarked, the rich and poor of that land had learned the value of the black stone.

"Through the whole Province of Cathay," says Polo, "certain black stones are dug from the mountains, which, put into the fire, burn like wood, and being kindled, preserve fire a long time, and if they be kindled in the evening they keep fire all the night."

Another important mineral product which even more than petroleum or coal is supposed to be essentially modern in its employment is asbestos. Polo had not only seen this but had realized exactly what it was, had found out its origin and had recognized its value. Curiously enough he attempts to explain the origin of a peculiar usage of the word salamander (the salamander having been supposed to be an animal which was not injured by fire) by reference to the incombustibility of asbestos. The whole passage as it appears in The Romance of Travel and Exploration deserves to be quoted. While discoursing about Dsungaria, Polo says:

"And you must know that in the mountain there is a substance from which Salamander is made. The real truth is that the Salamander is no beast as they allege in our part of the world, but is a substance found in the earth. Everybody can be aware that it can be no animal's nature to live in fire seeing that every animal is composed of all the four elements. Now I, Marco Polo, had a Turkish acquaintance who related that he had lived three years in that region on behalf of the Great Khan, in order to procure these salamanders for him. He said that the way they got them was by digging in that mountain till they found a certain vein. The substance of this vein was taken and crushed, and when so treated it divides, as it were, into fibres of wool, which they set forth to dry. When dry these fibres were pounded in a copper mortar and then washed so as to remove all the earth and to leave only the fibres, like fibres of wool. These were then spun and made into napkins." Needless to say this is an excellent description of asbestos.

It is not surprising, then, that the Twentieth Century so interested in travel and exploration should be ready to lay its tributes at the feet of Marco Polo, and that one of the important book announcements of recent years should be that of the publication of an annotated edition of Marco Polo from the hands of a modern explorer, who considered that there was no better way of putting definitely before the public in its true historical aspect the evolution of modern geographical knowledge with regard to Eastern countries.

It can scarcely fail to be surprising to the modern mind that Polo should practically have been forced into print. He had none of the itch of the modern traveler for publicity. The story of his travels he had often told and because of the wondrous tales he could unfold and the large numbers he found it frequently so necessary to use in order to give proper ideas of some of his wanderings, had acquired the nickname of Marco Millioni. He had never thought, however, of committing his story to writing or perhaps he feared the drudgery of such literary labor. After his return from his travels, however, he bravely accepted a patriot's duty of fighting for his native country on board one of her galleys and was captured by the Genoese in a famous sea-fight in the Adriatic in 1298. He was taken prisoner and remained in captivity in Genoa for nearly a year.

It was during this time that one Rusticiano, a writer by profession, was attracted to him and tempted him to tell him the complete story of his travels in order that they might be put into connected form. Rusticiano was a Pisan who had been a compiler of French romances and accordingly Polo's story was first told in French prose. It is not surprising that Rusticiano should have chosen French since he naturally wished his story of Polo's travels to be read by as many people as possible and realized that it would be of quite as much interest to ordinary folk as to the literary circles of Europe. How interesting the story is only those who have read it even with the knowledge acquired by all the other explorers since his time, can properly appreciate. It lacks entirely the egotistic quality that usually characterizes an explorer's account of his travels, and, indeed, there can scarcely fail to be something of disappointment because of this fact. No doubt a touch more of personal adventure would have added to the interest of the book. It was not a characteristic of the Thirteenth Century, however, to insist on the merely personal and consequently the world has lost a treat it might otherwise have had. There is no question, however, or the greatness of Polo's work as a traveler, nor of the glory that was shed by it on the Thirteenth Century. Like nearly everything else that was done in this marvelous century he represents the acme of successful endeavor in his special line down even to our own time.

It has sometimes been said that Marco Polo's work greatly influenced Columbus and encouraged him in his attempt to seek India by sailing around the globe. Of this, however, there is considerable doubt. We have learned in recent times, that a very definite tradition with regard to the possibility of finding land by sailing straight westward over the Atlantic existed long before Columbus' time.34 Polo's indirect influence on Columbus by his creation of an interest in geographical matters generally is much clearer. There can be no doubt of how much his work succeeded in drawing men's minds to geographical questions during the Fourteenth and Fifteenth centuries.

After Marco Polo, undoubtedly, the most enterprising explorer and interesting writer on Travel in the Thirteenth Century was John of Carpini, the author of a wonderful series of descriptions of things seen in Northern Asia. Like so many other travelers and explorers at this time John was a Franciscan Friar, and seems to have been one of the early companions and disciples of St. Francis of Assisi, whom he joined when he was only a young man himself. Before going on his missionary and ambassadorial expedition he had been one of the most prominent men in the order. He had much to do with its propagation among the Northern nations of Europe, and occupied successively the offices of custos or prior in Saxony and of Provincial in Germany. He seems afterwards to have been sent as an organizer into Spain and to have gone even as far as the Barbary coast.

It is not surprising, then, that when, in 1245, Pope Innocent IV. (sometime after the Mongol invasion of Eastern Europe and the disastrous battle of Legamites which threatened to place European civilization and Christianity in the power of the Tartars) resolved to send a mission to the Tartar monarch, John of Carpini was selected for the dangerous and important mission.

At this time Friar John was more than sixty years of age, but such was the confidence in his ability and in his executive power that everything on the embassy was committed to his discretion. He started from Lyons on Easter Day, 1245. He sought the counsel first of his old friend Wenceslaus, King of Bohemia, and from that country took with him another friar, a Pole, to act as his interpreter. The first stage in his journey was to Kiev, and from here, having crossed the Dnieper and the Don to the Volga, he traveled to the camp of Batu, at this time the senior living member of Jenghis Khan's family. Batu after exchanging presents allowed them to proceed to the court of the supreme Khan in Mongolia. As Col. Yule says, the stout-hearted old man rode on horseback something like three thousand miles in the next hundred days. The bodies of himself and companion had to be tightly bandaged to enable them to stand the excessive fatigue of this enormous ride, which led them across the Ural Mountains and River past the northern part of the Caspian, across the Jaxartes, whose name they could not find out, along the Dzungarian Lakes till they reached the Imperial Camp, called the Yellow Pavilion, near the Orkhon River. There had been an interregnum in the empire which was terminated by a formal election while the Friars were at the Yellow Pavilion, where they had the opportunity to see between three and four thousand envoys and deputies from all parts of Asia and Eastern Europe, who brought with them tributes and presents for the ruler to be elected.

It was not for three months after this, in November, that the Emperor dismissed them with a letter to the Pope written in Latin, Arabic, and Mongolian, but containing only a brief imperious assertion that the Khan of the Tartars was the scourge of God for Christianity, and that he must fulfill his mission. Then sad at heart, the ambassadors began their homeward journey in the midst of the winter. Their sufferings can be better imagined than described, but Friar John who does not dwell on them much tells enough of them to make their realization comparatively easy. They reached Kiev seven months later, in June, and were welcomed there by the Slavonic Christians as though arisen from the dead. From thence they continued their journey to Lyons where they delivered the Khan's letter to the Pope.

Friar John embodied the information that he had obtained in this journey in a book that has been called Liber Tartarorum (the Book of the Tartars or according to another manuscript, History of the Mongols whom we call Tartars). Col. Yule notes that like most of the other medieval monks' itineraries, it shows an entire absence of that characteristic traveler's egotism with which we have become abundantly familiar in more recent years, and contains very little personal narrative. We know that John was a stout man and this in addition to his age when he went on the mission, cannot but make us realize the thoroughly unselfish spirit with which he followed the call of Holy Obedience, to undertake a work that seemed sure to prove fatal and that would inevitably bring in its train suffering of the severest kind. Of the critical historical value of his work a good idea can be obtained from the fact, that half a century ago an educated Mongol, Galsang Gombeyev, in the Historical and Philological Bulletin of the Imperial Academy of St. Petersburg, reviewed the book and bore testimony to the great accuracy of its statements, to the care with which its details had been verified, and the evident personal character of all its observations.

Friar John's book attracted the attention of compilers of information with regard to distant countries very soon after it was issued, and an abridgment of it is to be found in the Encyclopedia of Vincent of Beauvais, which was written shortly after the middle of the Thirteenth Century. At the end of the Sixteenth Century Hakluyt published portions of the original work, as did Borgeron at the beginning of the Seventeenth Century. The Geographical Society of Paris published a fine edition of the work about the middle of the Nineteenth Century, and at the same time a brief narrative taken down from the lips of John's companion. Friar Benedict the Pole, which is somewhat more personal in its character and fully substantiates all that Friar John had written.

As can readily be understood the curiosity of his contemporaries was deeply aroused and Friar John had to tell his story many times after his return. Hence the necessity he found himself under of committing it to paper, so as to save himself from the bother of telling it all over again, and in order that his brother Franciscans throughout the world might have the opportunity to read it.

Col. Yule says "The book must have been prepared immediately after the return of the traveler, for the Friar Salimbene, who met him in France in the very year of his return (1247) gives us these interesting particulars: 'He was a clever and conversable man, well lettered, a great discourser, and full of diversity of experience. He wrote a big book about the Tartars (sic), and about other marvels that he had seen and whenever he felt weary of telling about the Tartars, he would cause this book of his to be read, as I have often heard and seen. (Chron. Fr. Salembene Parmensis in Monum. Histor. ad Provinceam Placent: Pertinentia, Parma 1857).'"

Another important traveler of the Thirteenth Century whose work has been the theme of praise and extensive annotation in modern times was William of Rubruk, usually known under the name of Rubruquis, a Franciscan friar, thought, as the result of recent investigations, probably to owe his cognomen to his birth in the little town of Rubruk in Brabant, who was the author of a remarkable narrative of Asiatic travel during the Thirteenth Century, and whose death seems to have taken place about 1298. The name Rubruquis has been commonly used to designate him because it is found in the Latin original of his work, which was printed by Hayluyt in his collection of Voyages at the end of the Sixteenth Century. Friar William was sent partly as an ambassador and partly as an explorer by Louis IX. of France into Tartary. At that time the descendants of Jenghis Khan ruled over an immense Empire in the Orient and King Louis was deeply interested in introducing Christianity into the East and if possible making their rulers Christians. About the middle of the Thirteenth Century a rumor spread throughout Europe that one of the nephews of the great Khan had embraced Christianity. St. Louis thought this a favorable opportunity for getting in touch with the Eastern Potentate and so he dispatched at least two missions into Tartary at the head of the second of which was William of Rubruk.

His accounts of his travels proved most interesting reading to his own and to many subsequent generations, perhaps to none more than our own. The Encyclopedia Britannica (ninth edition) says that the narrative of his journey is everywhere full of life and interest, and some details of his travels will show the reasons for this. Rubruk and his party landed on the Crimean Coast at Sudak or Soldaia, a port which formed the chief seat of communication between the Mediterranean countries and what is now Southern Russia. The Friar succeeded in making his way from here to the Great Khan's Court which was then held not far from Karakorum. This journey was one of several thousand miles. The route taken has been worked out by laborious study and the key to it is the description given of the country intervening between the basin of the Talas and Lake Ala-Kul. This enables the whole geography of the region, including the passage of the River Ili, the plain south of the Bal Cash, and the Ala-Kul itself, to be identified beyond all reasonable doubt.

The return journey was made during the summertime, and the route lay much farther to the north. The travelers traversed the Jabkan Valley and passed north of the River Bal Cash, following a rather direct course which led them to the mouth of the Volga. From here they traveled south past Derbend and Shamakii to the Uraxes, and on through Iconium to the coast of Cilicia, and finally to the port of Ayas, where they embarked for Cyprus. All during his travels Friar William made observations on men and cities, and rivers and mountains, and languages and customs, implements and utensils, and most of these modern criticism has accepted as representing the actual state of things as they would appear to a medieval sightseer. Occasionally during the period intervening between his time and our own, scholars who thought that they knew better, have been conceited enough to believe themselves in a position to point out glaring errors in Rubruquis' accounts of what he saw. Subsequent investigation and discovery have, as a rule, proved the accuracy of the earlier observations rather than the modern scholar's corrections. An excellent example of this is quoted in the Encyclopedia Britannica article on Rubruquis already referred to.

DOORWAY OF GIOTTO'S TOWER (FLORENCE)

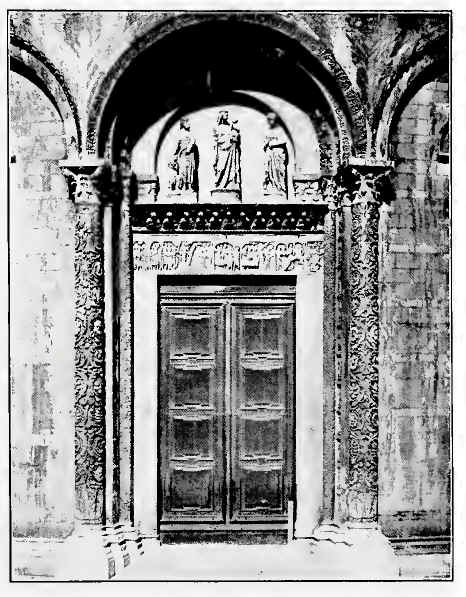

PRINCIPAL DOOR OF BAPTISTERY (PISA, DIOTISALVI)

The writer says: "This sagacious and honest observer is denounced as an ignorant and untruthful blunderer by Isaac Jacob Schmidt (a man no doubt of useful learning, of a kind rare in his day but narrow and long-headed and in natural acumen and candour far inferior to the Thirteenth Century friar whom he maligns), simply because the evidence of the latter as to the Turkish dialect of the Uigurs traversed a pet heresy long since exploded which Schmidt entertained, namely, that the Uigurs were by race and language Tibetan."

Some of the descriptions of the towns through which the travelers passed are interesting because of comparisons with towns of corresponding size in Europe. Karakorum, for instance, was described as a small city about the same size as the town of St. Denis near Paris. In Karakorum the ambassador missionary maintained a public disputation with certain pagan priests in the presence of three of the secretaries of the Khan. The religion of these umpires is rather interesting from its diversity: the first was a Christian, the second a Mohammedan, and the third a Buddhist. A very interesting feature of the disputation was the fact that the Khan ordered under pain of death that none of the disputants should slander, traduce, or abuse his adversaries, or endeavor by rumor or insinuations to excite popular indignation against them. This would seem to indicate that the great Tartar Khan who is usually considered to have been a cruel, ignorant despot, whose one quality that gave him supremacy was military valor, was really a large, liberal-minded man. His idea seems to have been to discover the truth of these different religions and adopt that one which was adjudged to have the best groundwork of reason for it. It is easy to understand, however, that such a disputation argued through interpreters wholly ignorant of the subject and without any proper understanding of the nice distinctions of words or any practise in conveying their proper significance, could come to no serious conclusion. The arguments, therefore, fell flat and a decision was not rendered.

Friar William's work was not unappreciated by his contemporaries and even its scientific value was thoroughly realized. It is not surprising, of course, that his great contemporary in the Franciscan order, Roger Bacon, should have come to the knowledge of his Brother Minorite's book and should have made frequent and copious quotations from it in the geographical section of his Opus Majus, which was written some time during the seventh decade of the Thirteenth Century. Bacon says that Brother William traversed the Oriental and Northern regions and the places adjacent to them, and wrote accounts of them for the illustrious King of France who sent him on the expedition to Tartary. He adds: "I have read his book diligently and have compared it with similar accounts." Roger Bacon recognized by a sort of scientific intuition of his own, certain passages which have proved to be the best in recent times. The description, for instance, of the Caspian was the best down to this time, and Friar William corrects the error made by Isidore, and which had generally been accepted before this, that the Caspian Sea was a gulf. Rubruk, as quoted by Roger Bacon, states very explicitly that it nowhere touches the ocean but is surrounded on all sides by land. For those who do not think that the foundations of scientific geography were laid until recent times, a little consultation of Roger Bacon's Opus Majus would undoubtedly be a revelation.

It is probably with regard to language that one might reasonably expect to find least that would be of interest to modern scholars in Friar William's book. As might easily have been gathered from previous references, however, it is here that the most frequent surprises as to the acuity of this medieval traveler await the modern reader. Scientific philology is so much a product of the last century, that it is difficult to understand how this old-time missionary was able to reach so many almost intuitive recognitions of the origin and relationships of the languages of the people among whom he traveled. He came in contact with the group of nations occupying what is now known as the Near East, whose languages, as is well known, have constituted a series of the most difficult problems with which philology had to deal until its thorough establishment on scientific lines enabled it to separate them properly. It is all the more surprising then, to find that Friar William should have so much in his book that even the modern philologist will read with attention and unstinted admiration.