Полная версия

Полная версияThe Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries

PORTRAIT OF POPE BONIFACE VIII. (GIOTTO, ROME)

He did much to complete in his time that arrangement and codification of canon law which his predecessors during the Thirteenth Century had so efficiently commenced. Like Innocent III. he has been much maligned because of his supposed attempt to make the governments of the time subservient to the Pope and to make the Church in each nation independent of the political government. With regard to the famous Bull Clericis Laicos, "thrice unhappy in name and fortune" as it has been designated, much more can be said in justification than is usually considered to be the case. Indeed the Rev. Dr. Barry, whose "Story of the Papal Monarchy" in the Stories of the Nations series has furnished the latest discussion of this subject, does not hesitate to declare that the Bull far from being subversive of political liberties or expressive of too arrogant a spirit on the part of the Church, was really an expression of a great principle that was to become very prominent in modern history, and the basis of many of the modern declarations of rights against the claims of tyranny.

He says in part:

"Imprudent, headlong, but in its main contention founded on history, this extraordinary state-paper declared that the laity had always been hostile to the clergy, and were so now as much as ever. But they possessed no jurisdiction over the persons, no claims on the property of the church, though they had dared to exact a tenth, nay, even a half, of its income for secular objects, and time-serving prelates had not resisted. Now, on no title whatsoever from henceforth should such taxes be levied without permission of the Holy See. Every layman, though king or emperor, receiving these moneys fell by that very act under anathema; every churchman paying them was deposed from his office; universities guilty of the like offense were struck with interdict.

"Robert of Winchelsea, Langton's successor as primate, shared Langton's views. He was at this moment in Rome, and had doubtless urged Boniface to come to the rescue of a frightened, down-trodden clergy, whom Edward I. would not otherwise regard. In the Parliament at Bury, this very year, the clerics refused to make a grant. Edward sealed up their barns. The archbishop ordered that in every cathedral the pope's interdiction should be read. Hereupon the chief-justice declared the whole clergy outlawed; they might be robbed or murdered without redress. Naturally, not a few gave way; a fifth, and then a fourth, of their revenue was yielded up. But Archbishop Robert alone, with all the prelates except Lincoln against him, and the Dominicans preaching at Paul's cross on behalf of the king, stood out, lost his lands, and was banished to a country parsonage. War broke out in Flanders. It was the saving of the archbishop. At Westminster Edward relented and apologized. He confirmed the two great charters; he did away with illegal judgments that infringed them. Next year the primate excommunicated those royal officers who had seized goods or persons belonging to the clergy, and all who had violated Magna Charta. The Church came out of this conflict exempt, or, more truly a self-governing estate of the realm. It must be considered as having greatly concurred towards the establishment of that fundamental law invoked long after by the thirteen American Colonies, 'No taxation without representation,' which is the corner stone of British freedom."

We have so often heard it said that there is nothing new under the sun, that finally the expression has come to mean very little, though its startling truth sometimes throws vivid light on historical events. Certainly the last place in the world that one would expect to find if not the origin, for all during the Thirteenth Century this great principle had been gradually asserting itself, at least, a wondrous confirmation of the principle on which our American revolution justified itself, would be in a papal document of the end of the Thirteenth Century. Here, however, is a distinguished scholar, who insists that the Colonists' contention that there must be no taxes levied unless they were allowed representation in some way in the body which determined the mode and the amount of taxation, received its first formal justification in history at the hands of a Roman Pontiff, nearly five centuries before the beginning of the quarrel between the Colonies and the Mother Country. The passage serves to suggest how much of what is modern had its definite though unsuspected origin, in this earlier time.

DECORATION THIRTEENTH CENTURY PSALTER MS.

XXIV

DEMOCRACY, CHRISTIAN SOCIALISM AND NATIONALITY

Democracy is a word to conjure with but it is usually considered that the thing it represents had its origin in the modern world much later than the period with which we are occupied. The idea that the people should be ready to realize their own rights, to claim their privileges and to ask that they should be allowed to rule themselves, is supposed ordinarily to be a product of the last century or two. Perhaps in this matter more than any other does the Thirteenth Century need interpretation to the modern mind, yet we think that after certain democratic factors and developments in the life of this period are pointed out and their significance made clear, it will become evident that the foundations of our modern democracy were deeply laid in the Thirteenth Century, and that the spirit of what was best in the aspiration of people to be ruled by themselves, for themselves, and of themselves had its birth in this precious seed time of so much that is important for our modern life.

Lest it should be thought that this idea of the development of democracy has been engendered merely in the enthusiastic ardor of special admiration for the author's favorite century, it seems well to call attention to the fact that historians in recent years have very generally emphasized the role that the Thirteenth Century played in the development of freedom. A typical example may be quoted from the History of Anglo-Saxon Freedom by Professor James K. Hosmer,31 who does not hesitate to say that "while in England representative government was gradually developing during this century, in Germany the cities were beginning to send deputies to the Imperial Parliament and the Emperor, Frederick II., was allowing a certain amount of representation in the Government of Sicily. In Spain, Alfonso the Wise, of Castile, permitted the cities to send representatives to the Cortez, and in France this same spirit developed to such a degree that a representative parliament met at the beginning of the Fourteenth Century." In none of these countries, however, unfortunately did the spirit of representative government continue to develop as in England and in many of them the privileges obtained in the Thirteenth Century were subsequently lost.

Certain phases of the rise of the democratic spirit have already been discussed, and the reader can only be referred to them now with the definite idea of recognizing in them the democratic tendencies of the time. What we have said about the trade guilds constitutes one extremely important element of the movement which will be further discussed in this chapter. After this comes the guild merchant in its various forms. After all the Hanseatic League was only one manifestation of these guilds. Its widespread influence in awakening in people's minds the realization that they could do for themselves much more, and secure success in their endeavors much better by their own united efforts, than by anything that their accepted political rulers could do or at least would do for them, will be readily appreciated by all who read that chapter.

Hansa must have been a great enlightener for the Teutonic peoples. The History of the league shows over and over again their political rulers rather interfering with than fostering their commercial prosperity. These rulers were always more than a little jealous of the wealth which the citizens of these growing towns in their realm were able to accumulate, and they showed it on more than one occasion. The history of the Hansa towns exhibits the citizens doing everything to dissemble the feelings of disaffection that inevitably came to them as the result of their appreciation of the fact, that they could rule themselves so much better than they were being ruled, and that they could accomplish so much more for themselves by their commercial combination with other cities than had ever been done for them by these hereditary princes, who claimed so much yet gave so little in their turn.

The training in self-government that came with the necessities for defense as well as for the protection of commercial visitors from other cities in the league, who trustfully came to deal with their people, was an education in democracy such as could not fail to bring results. The rise of the free cities in Germany represents the growth of the democratic spirit down to our own time, better than any other single set of manifestations that we have. The international relations of these cities did more, as we have said, to broaden men's minds and make them realize the brotherhood of man in spite of national boundaries than any other factor in human history. Commerce has always been a great leveler and such it proved to be in these early days in Germany, only it must not be thought that these German cities had but faint glimmerings of the great purpose they were engaged in, for seldom has the spirit of popular government risen higher than with them.

How clearly the Teutonic mind had grasped the idea of democracy can be best appreciated perhaps from the attitude of the Swiss in this matter. These hardy mountaineers whose difficult country and rather severe climate separate them effectually from the other nations, soon learned the advisability of ruling themselves for their own benefit. Before the end of the Thirteenth Century they had formed a defensive and offensive union among themselves against the Hapsburgs, and though for a time overborne by the influence of this house after its head ascended the Imperial throne, immediately on Rudolph's death they proceeded to unite themselves still more firmly together. They then formed the famous league of 1291 which represents so important a step in the democracy of modern times. The formal document which constituted this league a federal government deserves to be quoted. It is the first great declaration of independence, and its ideas were to crop out in many another declaration in the after times. It is an original document in the strictest sense of the word. It runs as follows:

"Know all men that we, the people of the valley of Uri, the community of the valley of Schwiz, and the mountaineers of the lower valley, seeing the malice of the times, have solemnly agreed and bound ourselves by oath to aid and defend each other with all our might and main, with our lives and property, both within and without our boundaries each at his own expense, against every enemy whatever who shall attempt to molest us, either singly or collectively. This is our ancient covenant. Whoever hath a lord let him obey him according to his bounden duty. We have decreed that we shall accept no magistrate in our valleys who shall have obtained his office for a price, or who is not a native or resident among us. Every difference among us shall be decided by our wisest men; and whoever shall reject their award shall be compelled by the other confederates. Whoever shall wilfully commit a murder shall suffer death, and he who shall attempt to screen the murderer from justice shall be banished from our valleys. An incendiary shall lose his privileges as a free member of the community, and whoever harbors him shall make good the damage. Whoever robs or molests another shall make full restitution out of the property he possesses among us. Everyone shall acknowledge the authority of a chief magistrate in either of the valleys. If internal quarrels arise, and one of the parties shall refuse fair satisfaction, the confederates shall support the other party. This covenant for our common weal, shall, God willing, endure forever."

In England democracy was fostered in the guilds, which, as we have already seen in connection with the cathedrals, proved the sources of education and intellectual development in nearly every mode of thought and art. The most interesting feature of these guilds was the fact that they were not institutions suggested to the workmen and tradesmen by those above them, but were the outgrowth of the spirit of self help and organization which, came over mankind during this century. At the beginning they were scarcely more than simple beneficial associations meant to be aids in times of sickness and trial, and to make the parting of families and especially the death of the head of the family not quite so difficult for the survivors, since affiliated brother workmen remained behind who would care for them. During this century, however, the spirit of democracy, that is the organized effort of the people to take care of themselves, better their conditions, and add to their own happiness, led to the development of the guilds in a fashion that it is rather difficult for generations of the modern time to understand, for our trades' unions do not, as yet at least, present anything that quite resembles their work in our times.

It was because of the effective social work of these guilds that Urbain Gohier, the well-known French socialist and writer on sociological subjects, was able to say not long ago in the North American Review:

"When the workmen of the European Continent demand 'the three eights'—eight hours of work, eight hours of rest and refreshment, physical and mental, and eight hours of sleep—some of them are aware of the fact that this reform already exists in the Anglo-Saxon countries; but all are ignorant of this other fact that, during the Middle Ages, in an immense number of labor corporations and cities, a work-day was often only nine, eight and even seven hours long. Nor have they ever been told that every Saturday, and on the eve of over two dozen holidays, work was stopped everywhere at four o'clock." The Saturday half holiday began it may be said even earlier, namely at the Vesper Hour which according to medieval church customs was some time between two and three p. m. and the same was true on the vigils, as the eves of the important church festivals were called.

The only possible way to give a reasonably good idea of the spirit of the old-time guilds which succeeded in accomplishing such a wonderful social revolution, is to quote some of their rules, which serve to show their intents and purposes at least, even though they may not always have fulfilled their aims. Their rules regard two things particularly—the religious and the social functions of the guild. There was a fine for absence from the special religious services held for the members but also a fine of equal amount for absence from the annual banquet. In this they resemble the rules of the religious orders which were coming to be widely known at the end of the Twelfth and the beginning of the Thirteenth Century, and according to which the members of the religious community were required quite as strictly to be present at daily recreation, that is, at the hour of conversation after meals, as at daily prayer. An interesting phase of the social rules of the guild is that a member was expected to bring his wife with him, or if not his wife then his sweetheart. They were franker in these matters in this simpler age and doubtless the custom encouraged matrimony a little bit more than our modern colder customs.

As giving a fair idea of the ordinances of the pre-Reformation guilds in their original shape the rules of the Guild of St. Luke at Lincoln, may be cited. St. Luke had been chosen as patron because according to tradition he was an artist as well as an evangelist. The patron saint was chosen always so that he might be a model of life as well as a protector in Heaven. Its members were the painters, guilders, stainers, and alabaster men of the city. The first rule provides that on the Sunday next after the feast of St. Luke all the brothers and sisters of the Guild shall, with their officers, go in procession from an appointed place, carrying a great candle, to the Cathedral Church of Lincoln, and there every two of the brethren and sisters shall offer one half-penny or more after their devotion, and then shall offer the great candle before an image of St. Luke within the church. And any who were absent without lawful cause shall forfeit one pound of wax to the sustentation of the said great candle.

On the same Sunday, "for love and amity and good communication to be had for the several weal of the fraternity," the guildmen dined together, every brother paying for himself and his wife, or sweetheart, the sum of four pence. Absentees were fined one pound of wax towards the aforesaid, candle.

The third rule provided that four "mornspeeches"—that its business meetings—should be held each year, "for ordering and good rule to be had and made amongst them." Absentees from a mornspeech forfeited one pound of wax to St. Luke's candle. Another rule provided that the decision of ambiguities or doubts about the forfeitures prescribed should be referred to the mayor and four aldermen of the city. Rules 4 to 11, and also 13, regulate the taking of apprentices and the setting up in trade; forbid the employing of strangers; provide for the settlement of disputes and the examination of work not sufficiently done after the sample. Already the tendency to limit the number of workmen that might be employed which was later to prove a stumbling block to artistic progress is to be noted. On the other hand the effort to keep work up to a certain standard, which was to mean so much for artistic accomplishment in the next few generations must be noted as a compensatory feature of the Guild regulations.

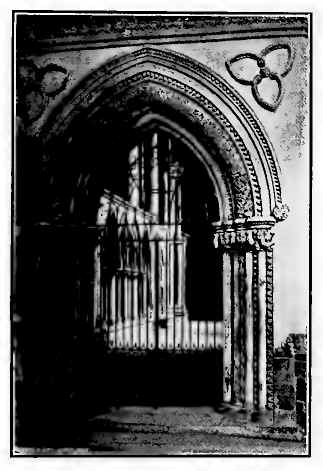

DOORWAY (LINCOLN)

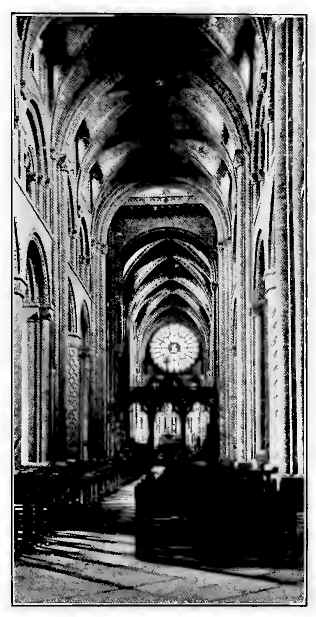

NAVE (DURHAM CATHEDRAL)

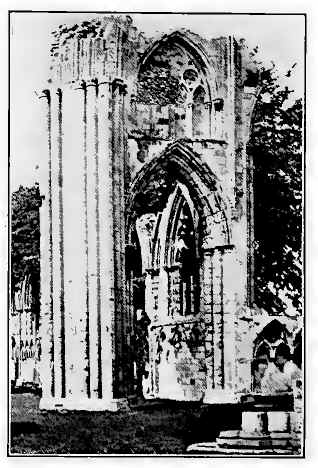

BROKEN ARCH (ST. MARY'S, YORK, CLIMAX OF GOTHIC)

Rule 12 directs that "when it shall happen any brother or sister of the said fraternity to depart and decease from the world, at his first Mass the gracemen and wardens (skyvens) for the time being shall offer of the goods and chattels of the said fraternity, two pence; and at his eighth day, or thirtieth day, every brother and sister shall give to a poor creature a token made by the dean, for which tokens every brother and sister shall pay the dean a fixed sum of money, and with the money thus raised he shall buy white bread to give to the poor creatures" holding the tokens, the bread to be distributed at the church of the parish in which the deceased lived.

This twelfth rule with regard to the manner of giving charity is particularly striking, because it shows a deliberate effort to avoid certain dangers, the evil possibilities of which our modern organized charity has emphasized. According to this rule of the Guild of St. Luke's at Lincoln, all the members were bound to give a certain amount in charity, for the benefit of a deceased member. This was not, however, by direct alms, but by means of tokens for which they paid a fixed price to the Dean, who redeemed the tokens when they were presented by the deserving poor. This guaranteed that each member would give the fixed sum in charity and at the same time safeguarded the almsgiving from any abuses, since the member of the guild himself would be likely to know something of the poor person and his deservingness, and if not there was always the question of the Dean being informed with regard to the needs of the case. All of this was accomplished, however, without hurting the feelings of the recipients of the charity, since they felt that it was done not for them but for the benefit of a deceased member.

How much the guilds came to influence the life of the people during the next two centuries may be best appreciated from their great increase in number and wealth.

In England, it is computed that at the beginning of the Sixteenth Century there were thirty thousand of these institutions spread over the country. The county of Norfolk alone had nine hundred, of which number the small town of Wymondham had at least eleven still known by names, one—the Guild of Holy Trinity, Wymondham—being possessed of a guild-hall of its own, whilst it and the other guilds of the town are said to have been "well endowed with lands and tenements." In Bury St. Edmunds, Suffolk, there were twenty-three guilds; Boston, Lincolnshire, had fourteen, of which the titles and other particulars are known, whilst in London their number must have been very great. Of the London trade guilds, Stow, the Elizabethan antiquary, records the names of sixty of sufficient importance to entitle their representatives to places at the civic banquets in the reign of Henry VIII. Many of them are still in existence, having been spared at the time of the Reformation on the plea that they were trading or secular associations. Fifteen of the largest of them—including the merchant tailors, the goldsmiths and the stationers—have at the present time an annual income of over $50,000 each.

The reasons for their popularity can be readily found in the many social needs which they cared for. Socialistic cooperation has, perhaps, never been carried so far as in these medieval institutions which were literally "of the people, by the people, and for the people." Often their regulation made provisions for insurance against poverty, fire, and sometimes against burglary. Frequently they provided schoolmasters for the schools. Their funds they loaned out to needy brethren in small sums on easy terms, whilst trade and other disputes likely to give rise to ill-feeling and contention were constantly referred to the guilds for arbitration. One of the rules of the Guild of our Lady at Wymondham thus ordains, that for no manner of cause should any of the brothers or sisters of the fraternity go to law till the officers of the guild had been informed of the circumstances and had done their best to settle the dispute and restore "unity and love betwixt the parties." To assist at the burial of deceased brethren, and to aid in providing for the celebration of obits for the repose of their souls, were duties incumbent on all, defaulters without good excuse being subject to fines and censure.

It must not be thought that these tendencies to true democracy were confined to the trades guilds, however. The historian of the merchant guilds has demonstrated that they had the same spirit and this was especially true for the great guild merchant. He says:

"To this category of powerful affinities must be added the Gild Merchant. The latter was from the outset a compact body emphatically characterized by fraternal solidarity of interests, a protective union that naturally engendered a consciousness of strength and a spirit of independence. As the same men generally directed the counsels of both the town and the Gild, there would be a gradual, unconscious extension of the unity of the one to the other, the cohesive force of the Gild making itself felt throughout the whole municipal organism. But the influence of the fraternity was material as well as moral. It constituted a bond of union between the heterogeneous sokes (classes of tenants) of a borough; the townsmen might be exclusively amenable to the courts of different lords, but, if engaged in trade within the town, they were all members of one and the same Gild Merchant. The independent regulation of trade also accustomed the burgesses to self-government, and constituted an important step toward autonomy; the town judiciary was always more dependent upon the crown or mesne lord than was the Gild Merchant."

Because of the supreme interest in everything connected with Shakespeare, the existence of one of the most important guilds in Stratford, has led to the illustration of guilds' works there better than for any English town during this period. The Guild of the Holy Cross was the most important institution of Stratford and enthusiastic Shakespeare scholars have applied themselves to find out every detail of its history as far as it is now available, in order to make clear the conditions—social and religious—that existed in the great dramatist's birthplace. Halliwell, in his Descriptive Calendar of the Records of Stratford on Avon, and Sidney Lee, in his Stratford on Avon in the Time of the Shakespeares, have gathered together much of this information:—"The Guild has lasted, wrote its chief officer in 1309, for many, many years and its beginning was from time whereunto the memory of man reaches not." Bowden, in his volume on the Religion of Shakespeare, has a number of the most important details with regard to Stratford's Guild. The earliest extant documents with regard to it are from the Reign of Henry III., 1216-1272, and include a deed of gift by one William Sede, of a tenement to the Guild, and an indulgence granted October 7th, 1270, by Giffard, Bishop of Wooster, of forty days to all sincere penitents who after having duly confessed had conferred benefits on the Guild.