Полная версия

Полная версияThe Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries

IX

LIBRARIES AND BOOKMEN

As the Thirteenth Century begins some 250 years before the art of printing was introduced, it would seem idle to talk of libraries and especially of circulating libraries during this period and quite as futile to talk of bookmen and book collectors. Any such false impression, however, is founded entirely upon a lack of knowledge of the true state of affairs during this wonderful period. A diocesan council held in Paris in the year 1212, with other words of advice to religious, recalled to them the duty that they had to lend such books as they might possess, with proper guarantee for their return, of course, to those who might make good use of them. The council, indeed, formally declared that the lending of books was one of the works of mercy. The Cathedral chapter of Notre Dame at Paris was one of the leaders in this matter and there are records of their having lent many books during the Thirteenth Century. At most of the abbeys around Paris there were considerable libraries and in them also the lending custom obtained. This is especially true of the Abbey of St. Victor of which the rule and records are extant.

Of course it will be realized that the number of books was not large, but on the other hand it must not be forgotten that many of them were works of art in every particular, and some of them that have come down to us continue to be even to the present day among the most precious bibliophilic treasures of great state and city libraries. Their value depends not alone on their antiquity but on their perfection as works of art. In general it may be said that the missals and office books, and the prayer books made for royal personages and the nobility at this time, are yet counted among the best examples of bookmaking the world has ever seen. It is not surprising that such should be the case since these books were mainly meant for use in the Cathedrals and the chapels, and these edifices were so beautiful in every detail that the generations that erected them could not think of making books for use in them, that would be unworthy of the artistic environment for which they were intended. With the candlesticks, the vessels, and implements used in the ceremonial surpassing works of art, with every form of decoration so nearly perfect as to be a source of unending admiration, with the vestments and altar linens specimens of the most exquisite handiwork of their kind that had ever been made, the books associated with them had to be excellent in execution, expressive of the most refined taste and finished with an attention utterly careless of the time and labor that might be required, since the sole object was to make everything as absolutely beautiful as possible. Hence there is no dearth of wonderful examples of the beautiful bookmaking of this century in all the great libraries of the world.

The libraries themselves, moreover, are of surpassing interest because of their rules and management, for little as it might be expected this wonderful century anticipated in these matters most of our very modern library regulations. The bookmen of the time not only made beautiful books, but they made every provision to secure their free circulation and to make them available to as many people as was consonant with proper care of the books and the true purposes of libraries. This is a chapter of Thirteenth Century history more ignored perhaps than any other, but which deserves to be known and will appeal to our century more perhaps than to any intervening period.

The constitutions of the Abbey St. Victor of Paris give us an excellent idea at once of the solicitude with which the books were guarded, yet also of the careful effort that was made to render them useful to as many persons as possible. One of the most important rules at St. Victor was that the librarian should know the contents of every volume in the library, in order to be able to direct those who might wish to consult the books in their selection, and while thus sparing the books unnecessary handling also save the readers precious time. We are apt to think that it is only in very modern times that this training of librarians to know their books so as to be of help to the readers was insisted on. Here, however, we find it in full force seven centuries ago. It would be much more difficult in the present day to know all the books confided to his care, but some of the librarians at St. Victor were noted for the perfection of their knowledge in this regard and were often consulted by those who were interested in various subjects.

In his book on the Thirteenth Century15 M. A. Lecoy de la Marche says that in France, at least, circulating libraries were quite common. As might be expected of the people of so practical a century, it was they who first established the rule that a book might be taken out provided its value were deposited by the borrower. Such lending libraries were to be found at the Sorbonne, at St. Germain des Prés, as well as at Notre Dame. There was also a famous library at this time at Corbie but practically every one of the large abbeys had a library from which books could be obtained. Certain of the castles of the nobility, as for instance that of La Ferte en Ponthieu, had libraries, with regard to which there is a record, that the librarian had the custom of lending certain volumes, provided the person was known to him and assumed responsibility for the book.

Some of the regulations of the libraries of the century have an interest all their own from the exact care that was required with regard to the books. The Sorbonne for instance by rule inflicted a fine upon anyone who neglected to close large volumes after he had been making use of them. Many a librarian of the modern times would be glad to put into effect such a regulation as this. A severe fine was inflicted upon any library assistant who allowed a stranger to go into the library alone, and another for anyone who did not take care to close the doors. It seems not unlikely that these regulations, as M. Lecoy de la Marche says, were in vigor in many of the ecclesiastical and secular libraries of the time.

Some of the regulations of St. Victor are quite as interesting and show the liberal spirit of the time as well as indicate how completely what is most modern in library management was anticipated. The librarian had the charge of all the books of the community, was required to have a detailed list of them and each year to have them in his possession at least three times. On him was placed the obligation to see that the books were not destroyed in any way, either by parasites of any kind or by dampness. The librarian was required to arrange the books in such a manner as to make the finding of them prompt and easy. No book was allowed to be borrowed unless some pledge for its safe return were left with the librarian. This was emphasized particularly for strangers who must give a pledge equal to the value of the book. In all cases, however, the name of the borrower had to be taken, also the title of the book borrowed, and the kind of pledge left. The larger and more precious books could not be borrowed without the special permission of the superior.

The origin of the various libraries in Paris is very interesting as proof that the mode of accumulating books was nearly the same as that which enriches university and other such libraries at the present time. The library of La St. Chapelle was founded by Louis IX, and being continuously enriched by the deposit therein of the archives of the kingdom soon became of first importance. Many precious volumes that were given as presents to St. Louis found their way into this library and made it during his lifetime the most valuable collection of books in Paris. Louis, moreover, devoted much time and money to adding to the library. He made it a point whenever on his journeys he stopped, at abbeys or other ecclesiastical institutions, to find out what books were in their library that were not at La Saint Chapelle and had copies of these made. His intimate friendship with Robert of Sorbonne, with St. Thomas of Aquin, with Saint Bonaventure, and above all with Vincent of Beauvais, the famous encyclopedist of the century, widened his interest in books and must have made him an excellent judge of what he ought to procure to complete the library. It was, as we shall see, Louis' munificent patronage that enabled Vincent to accumulate that precious store of medieval knowledge, which was to prove a mine of information for so many subsequent generations.

From the earliest times certain books, mainly on medicine, were collected at the Hotel Dieu, the great hospital of Paris, and this collection was added to from time to time by the bequests of physicians in attendance there. This was doubtless the first regular hospital library, though probably medical books had also been collected at Salernum. The principal colleges of the universities also made collections of books, some of them very valuable, though as a rule, it would seem as if no attempt was made to procure any other books than those which were absolutely needed for consultation by the students. The best working library at Paris was undoubtedly that of the Sorbonne, of which indeed its books were for a long time its only treasures. For at first the Sorbonne was nothing but a teaching institution which only required rooms for its lectures, and usually obtained these either from the university authorities or from the Canons of the Cathedral and possessed no property except its library. From the very beginning the professors bequeathed whatever books they had collected to its library and this became a custom. It is easy to understand that within a very short time the library became one of the very best in Europe. While most of the other libraries were devoted mainly to sacred literature, the Sorbonne came to possess a large number of works of profane literature. Interesting details with regard to this library of the Sorbonne and its precious treasures have been given by M. Leopold Delisle, in the second volume of Le Cabinet des Manuserits, describing the MSS. of the Bibliothèque Nationale at Paris. According to M. Lecoy de la Marche, this gives an excellent idea of the persevering efforts which must have been required, to bring together so many bibliographic treasures at a time when books were such a rarity, and consequently enables us better almost than anything else, to appreciate the enthusiasm of the scholars of these early times and their wonderful efforts to make the acquisition of knowledge easier, not only for their own but for succeeding generations. When we recall that the library of the Sorbonne was, during the Thirteenth Century, open not only to the professors and students of the Sorbonne itself, but also to those interested in books and in literature who might come from elsewhere, provided they were properly accredited, we can realize to the full the thorough liberality of spirit of these early scholars. Usually we are prone to consider that this liberality of spirit, even in educational matters, came much later into the world.

In spite of the regulations demanding the greatest care, it is easy to understand that after a time even books written on vellum or parchment would become disfigured and worn under the ardent fingers of enthusiastic students, when comparatively so few copies were available for general use. In order to replace these worn-out copies every abbey had its own scriptorium or writing room, where especially the younger monks who were gifted with plain handwriting were required to devote certain hours every day to the copying of manuscripts. Manuscripts were borrowed from neighboring libraries and copied, or as in our modern day exchanges of duplicate copies were made, so as to avoid the risk that precious manuscripts might be subject to on the journeys from one abbey to another. How much the duty of transcription was valued may be appreciated from the fact, that in some abbeys every novice was expected to bring on the day of his profession as a religious, a volume of considerable size which had been carefully copied by his own hands.

Besides these methods of increasing the number of books in the library, a special sum of money was set aside in most of the abbeys for the procuring of additional volumes for the library by purchase. Usually this took the form of an ecclesiastical regulation requiring that a certain percentage of the revenues should be spent on the libraries. Scholars closely associated with monasteries frequently bequeathed their books and besides left money or incomes to be especially devoted to the improvement of the library. It is easy to understand that with all these sources of enrichment many abbeys possessed noteworthy libraries. To quote only those of France, important collections of books were to be found at Cluny, Luxeuil, Fleury, Saint-Martial, Moissac, Mortemer, Savigny, Fourcarmont, Saint Père de Chartres, Saint Denis, Saint-Maur-des-Fossés, Saint Corneille de Compiègne, Corbie, Saint-Amand, Saint-Martin de Tournai, where Vincent de Beauvais said that he found the greatest collections of manuscripts that existed in his time, and then especially the great Parisian abbeys already referred to, Saint-Germain-des-Prés, Saint Victor, Saint-Martin-des-Champs, the precious treasures of which are well known to all those who are familiar with the Bibliothèque Nationale of Paris, of whose manuscript department their relics constitute the most valuable nucleus.

Some of the bequests of books that were made to libraries at this time are interesting, because they show the spirit of the testators and at the same time furnish valuable hints as to the consideration in which books were held and the reverent care of their possessors for them. Peter of Nemours, the Bishop of Paris, when setting out on the crusades with Louis IX. bequeathed to the famous Abbey of St. Victor, his Bible in 22 volumes, which was considered one of the finest copies of the scriptures at that time in existence. To the Abbey of Olivet he gave his Psalter with Glosses, besides the Epistles of St. Paul and his Book of Sentences, by which is evidently intended the well-known work with that title by the famous Peter Lombard. Finally he gave to the Cathedral of Paris all the rest of his books. Besides these he had very little to leave. It is typical of the reputation of Paris in that century and the devotion of her churchmen to learning and culture, that practically all of the revenues that he considered due him for his personal services had been invested in books, which he then disposed of in such a way as would secure their doing the greatest possible good to the largest number of people. His Bible was evidently given to the abbey of St. Victor because it was the sort of work that should be kept for the occasional reference of the learned rather than the frequent consultation of students, who might very well find all that they desired in other and less valuable copies. His practical intention with regard to his books can be best judged from his gift to Notre Dame, which, as we have noted already possessed a very valuable library that was allowed to circulate among properly accredited scholars in Paris.

According to the will of Peter Ameil, Archbishop of Narbonne, which is dated 1238, he gave his books for the use of the scholars whom he had supported at the University of Paris and they were to be deposited in the Library at Notre Dame, but on condition that they were not to be scattered for any reason nor any of them sold or abused. The effort of the booklover to keep his books together is characteristic of all the centuries since, only most people will be surprised to find it manifesting itself so early in bibliophilic history. The Archbishop reserved from his books, however, his Bible for his own church. Before his death he had given the Dominicans in his diocese many books from his library. This churchman of the first half of the Thirteenth Century seems evidently to deserve a prominent place among the bookmen of all times.

There are records of many others who bequeathed libraries and gave books during their lifetime to various institutions, as may be found in the Literary History of France,16 already mentioned, as well as in the various histories of the University of Paris. Many of these gifts were made on condition that they should not be sold and the constantly recurring condition made by these booklovers is that their collections should be kept together. The libraries of Paris were also in the market for books, however, and there is proof that the Sorbonne purchased a number of volumes because the cost price of them was noted inside the cover quite as libraries do in our own days. When we realize the forbidding cost of them, it is surprising that there should be so much to say about them and so many of them constantly changing hands. An ordinary folio volume probably cost from 400 to 500 francs in our values, that is between $80 and $100.

While the older abbeys of the Benedictines and other earlier religious orders possessed magnificent collections of books, the newer orders of the Thirteenth Century, the Mendicants, though as their name indicates they were bound to live by alms given them by the faithful, within a short time after their foundation began to take a prominent part in the library movement. It was in the southern part of France that the Dominicans were strongest and so there is record of regulations for libraries made at Toulouse in the early part of the Thirteenth Century. In Paris, in 1239, considerable time and discussion was devoted in one of the chapters of the order to the question of how books should be kept, and how the library should be increased. With regard to the Franciscans, though their poverty was, if possible, stricter, the same thing is known before the end of the century. In both orders arrangements were made for the copying of important works and it is, of course, to the zeal and enthusiasm of the younger members of these orders for this copying work, that we owe the preservation by means of a large number of manuscript copies, of the voluminous writings of such men as Albertus Magnus, St. Thomas, Duns Scotus and others.

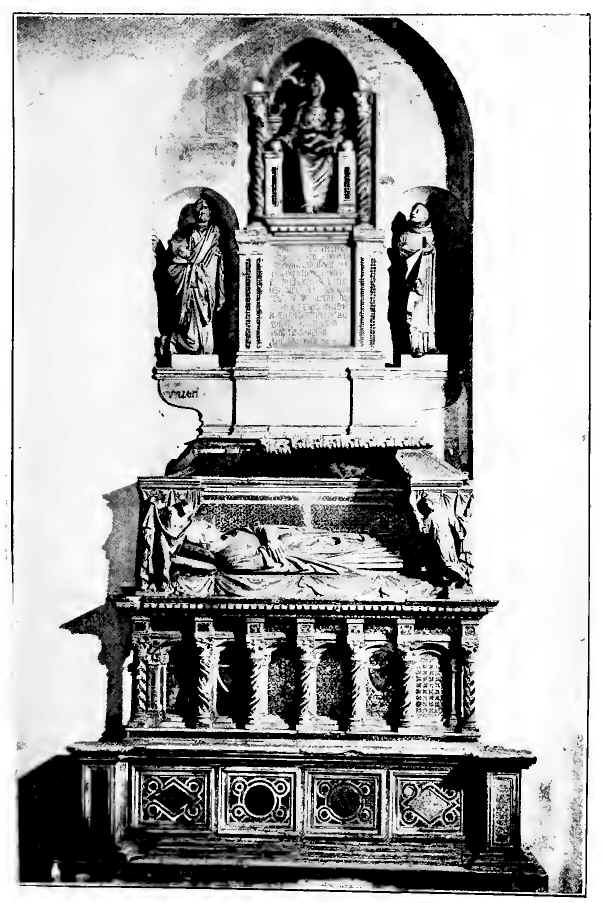

MONUMENT OF CARDINAL DE BRAY (ARNOLFO)

While the existence of libraries of various kinds, and even circulating libraries, in the Thirteenth Century may seem definitely settled, it will appear to most people that to speak of book collecting at this time must be out of place. That fad is usually presumed to be of much later origin and indeed to be comparatively recent in its manifestations. We have said enough already, however, of the various collections of books in libraries especially in France to show that the book collector was abroad, but there is much more direct evidence of this available from an English writer. Richard de Bury's Philobiblon is very well known to all who are interested in books for their own sake, but few people realize that this book practically had its origin in the Thirteenth Century. The writer was born about the beginning of the last quarter of that century, had completed his education before its close, and it is only reasonable to attribute to the formative influences at work in his intellectual development as a young man, the germs of thought from which were to come in later life the interesting book on bibliophily, the first of its kind, which was to be a treasure for book-lovers ever afterwards.

Philobiblon tells us, among other things, of Richard's visits to the continent on an Embassy to the Holy See and on subsequent occasions to the Court of France, and the delight which he experienced in handling many books which he had never seen before, in buying such of them as his purse would allow, or his enthusiasm could tempt from their owners and in conversing with those who could tell him about books and their contents. Such men were the chosen comrades of his journeys, sat with him at table, as Mr. Henry Morley tells us in his English Writers (volume IV, page 51), and were in almost constant fellowship with him. It was at Paris particularly that Richard's heart was satisfied for a time because of the great treasures he found in the magnificent libraries of that city. He was interested, of course, in the University and the opportunity for intellectual employment afforded by Academic proceedings, but above all he found delight in books, which monks and monarchs and professors and churchmen of all kinds and scholars and students had gathered into this great intellectual capital of Europe at that time. Anyone who thinks the books were not valued quite as highly in the Thirteenth Century as at the present time should read the Philobiblon. He is apt to rise from the reading of it with the thought that it is the modern generations who do not properly appreciate books.

One of the early chapters of Philobiblon argues that books ought always to be bought whatever they cost, provided there are means to pay for them, except in two cases, "when they are knavishly overcharged, or when a better time for buying is expected." "That sun of men, Solomon," Richard says, "bids us buy books readily and sell them unwillingly, for one of his proverbs runs, 'Buy the truth and sell it not, also wisdom and instruction and understanding.'" Richard in his own quaint way thought that most other interests in life were only temptations to-draw men away from books. In one famous paragraph he has naively personified books as complaining with regard to the lack of attention men now display for them and the unworthy objects, in Richard's eyes at least, upon which they fasten their affections instead, and which take them away from the only great life interest that is really worth while—books.

"Yet," complain books, "in these evil times we are cast out of our place in the inner chamber, turned out of doors, and our place taken by dogs, birds, and the two-legged beast called woman. But that beast has always been our rival, and when she spies us in a corner, with no better protection than the web of a dead spider, she drags us out with a frown and violent speech, laughing us to scorn as useless, and soon counsels us to be changed into costly head-gear, fine linen, silk and scarlet double dyed, dresses and divers trimmings, linens and woolens. And so," complain the books still, "we are turned out of our homes, our coats are torn from our backs, our backs and sides ache, we lie about disabled, our natural whiteness turns to yellow—without doubt we have the jaundice. Some of us are gouty, witness our twisted extremities. Our bellies are griped and wrenched and are consumed by worms; on each side the dirt cleaves to us, nobody binds up our wounds, we lie ragged and weep in dark corners, or meet with Job upon a dunghill, or, as seems hardly fit to be said, we are hidden in abysses of the sewers. We are sold also like slaves, and lie as unredeemed pledges in taverns. We are thrust into cruel butteries, to be cut up like sheep and cattle; committed to Jews, Saracens, heretics and Pagans, whom we always dread as the plague, and by whom some of our forefathers are known to have been poisoned."

Richard De Bury must not be thought to have been some mere wandering scholar of the beginning of the Fourteenth Century, however, for he was, perhaps, the most important historical personage, not even excepting royalty or nobility, of this era and one of the striking examples of how high a mere scholar might rise in this period quite apart from any achievement in arms, though this is usually supposed to be almost the only basis of distinguished reputation and the reason for advancement at this time. While he was only the son of a Norman knight, Aungervyle by name, born at Bury St. Edmund's, he became the steward of the palace and treasurer of the royal wardrobe, then Lord Treasurer of England and finally Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal. While on a mission to the Pope he so commended himself to the Holy See that it was resolved to make him the next English bishop. Accordingly he was made Bishop of Durham shortly after and on the occasion of his installation there was a great banquet at which the young King and Queen, the Queen Mother Isabelle, the King of Scotland, two Archbishops, five bishops, and most of the great English lords were present. At this time the Scots and the English were actually engaged in war with one another and a special truce was declared, in order to allow them to join in the celebration of the consecration of so distinguished an individual to the See of Durham near the frontier.