Полная версия

Полная версияПолная версия:

A Journal of the Plague Year

I was surprised, not at the sight of so many thieves only, but at the circumstances I was in; being now to thrust myself in among so many people, who for some weeks had been so shy of myself that if I met anybody in the street I would cross the way from them.

They were equally surprised, though on another account. They all told me they were neighbours, that they had heard anyone might take them, that they were nobody's goods, and the like. I talked big to them at first, went back to the gate and took out the key, so that they were all my prisoners, threatened to lock them all into the warehouse, and go and fetch my Lord Mayor's officers for them.

They begged heartily, protested they found the gate open, and the warehouse door open; and that it had no doubt been broken open by some who expected to find goods of greater value: which indeed was reasonable to believe, because the lock was broke, and a padlock that hung to the door on the outside also loose, and an abundance of the hats carried away.

At length I considered that this was not a time to be cruel and rigorous; and besides that, it would necessarily oblige me to go much about, to have several people come to me, and I go to several whose circumstances of health I knew nothing of; and that even at this time the plague was so high as that there died 4000 a week; so that in showing my resentment, or even in seeking justice for my brother's goods, I might lose my own life; so I contented myself with taking the names and places where some of them lived, who were really inhabitants in the neighbourhood, and threatening that my brother should call them to an account for it when he returned to his habitation.

Then I talked a little upon another foot with them, and asked them how they could do such things as these in a time of such general calamity, and, as it were, in the face of God's most dreadful judgements, when the plague was at their very doors, and, it may be, in their very houses, and they did not know but that the dead-cart might stop at their doors in a few hours to carry them to their graves.

I could not perceive that my discourse made much impression upon them all that while, till it happened that there came two men of the neighbourhood, hearing of the disturbance, and knowing my brother, for they had been both dependents upon his family, and they came to my assistance. These being, as I said, neighbours, presently knew three of the women and told me who they were and where they lived; and it seems they had given me a true account of themselves before.

This brings these two men to a further remembrance. The name of one was John Hayward, who was at that time undersexton of the parish of St Stephen, Coleman Street. By undersexton was understood at that time gravedigger and bearer of the dead. This man carried, or assisted to carry, all the dead to their graves which were buried in that large parish, and who were carried in form; and after that form of burying was stopped, went with the dead-cart and the bell to fetch the dead bodies from the houses where they lay, and fetched many of them out of the chambers and houses; for the parish was, and is still, remarkable particularly, above all the parishes in London, for a great number of alleys and thoroughfares, very long, into which no carts could come, and where they were obliged to go and fetch the bodies a very long way; which alleys now remain to witness it, such as White's Alley, Cross Key Court, Swan Alley, Bell Alley, White Horse Alley, and many more. Here they went with a kind of hand-barrow and laid the dead bodies on it, and carried them out to the carts; which work he performed and never had the distemper at all, but lived about twenty years after it, and was sexton of the parish to the time of his death. His wife at the same time was a nurse to infected people, and tended many that died in the parish, being for her honesty recommended by the parish officers; yet she never was infected neither.

He never used any preservative against the infection, other than holding garlic and rue in his mouth, and smoking tobacco. This I also had from his own mouth. And his wife's remedy was washing her head in vinegar and sprinkling her head-clothes so with vinegar as to keep them always moist, and if the smell of any of those she waited on was more than ordinary offensive, she snuffed vinegar up her nose and sprinkled vinegar upon her head-clothes, and held a handkerchief wetted with vinegar to her mouth.

It must be confessed that though the plague was chiefly among the poor, yet were the poor the most venturous and fearless of it, and went about their employment with a sort of brutal courage; I must call it so, for it was founded neither on religion nor prudence; scarce did they use any caution, but ran into any business which they could get employment in, though it was the most hazardous. Such was that of tending the sick, watching houses shut up, carrying infected persons to the pest-house, and, which was still worse, carrying the dead away to their graves.

It was under this John Hayward's care, and within his bounds, that the story of the piper, with which people have made themselves so merry, happened, and he assured me that it was true. It is said that it was a blind piper; but, as John told me, the fellow was not blind, but an ignorant, weak, poor man, and usually walked his rounds about ten o'clock at night and went piping along from door to door, and the people usually took him in at public-houses where they knew him, and would give him drink and victuals, and sometimes farthings; and he in return would pipe and sing and talk simply, which diverted the people; and thus he lived. It was but a very bad time for this diversion while things were as I have told, yet the poor fellow went about as usual, but was almost starved; and when anybody asked how he did he would answer, the dead cart had not taken him yet, but that they had promised to call for him next week.

It happened one night that this poor fellow, whether somebody had given him too much drink or no – John Hayward said he had not drink in his house, but that they had given him a little more victuals than ordinary at a public-house in Coleman Street – and the poor fellow, having not usually had a bellyful for perhaps not a good while, was laid all along upon the top of a bulk or stall, and fast asleep, at a door in the street near London Wall, towards Cripplegate-, and that upon the same bulk or stall the people of some house, in the alley of which the house was a corner, hearing a bell which they always rang before the cart came, had laid a body really dead of the plague just by him, thinking, too, that this poor fellow had been a dead body, as the other was, and laid there by some of the neighbours.

Accordingly, when John Hayward with his bell and the cart came along, finding two dead bodies lie upon the stall, they took them up with the instrument they used and threw them into the cart, and, all this while the piper slept soundly.

From hence they passed along and took in other dead bodies, till, as honest John Hayward told me, they almost buried him alive in the cart; yet all this while he slept soundly. At length the cart came to the place where the bodies were to be thrown into the ground, which, as I do remember, was at Mount Mill; and as the cart usually stopped some time before they were ready to shoot out the melancholy load they had in it, as soon as the cart stopped the fellow awaked and struggled a little to get his head out from among the dead bodies, when, raising himself up in the cart, he called out, 'Hey! where am I?' This frighted the fellow that attended about the work; but after some pause John Hayward, recovering himself, said, 'Lord, bless us! There's somebody in the cart not quite dead!' So another called to him and said, 'Who are you?' The fellow answered, 'I am the poor piper. Where am I?' 'Where are you?' says Hayward. 'Why, you are in the dead-cart, and we are going to bury you.' 'But I an't dead though, am I?' says the piper, which made them laugh a little though, as John said, they were heartily frighted at first; so they helped the poor fellow down, and he went about his business.

I know the story goes he set up his pipes in the cart and frighted the bearers and others so that they ran away; but John Hayward did not tell the story so, nor say anything of his piping at all; but that he was a poor piper, and that he was carried away as above I am fully satisfied of the truth of.

It is to be noted here that the dead-carts in the city were not confined to particular parishes, but one cart went through several parishes, according as the number of dead presented; nor were they tied to carry the dead to their respective parishes, but many of the dead taken up in the city were carried to the burying-ground in the out-parts for want of room.

I have already mentioned the surprise that this judgement was at first among the people. I must be allowed to give some of my observations on the more serious and religious part. Surely never city, at least of this bulk and magnitude, was taken in a condition so perfectly unprepared for such a dreadful visitation, whether I am to speak of the civil preparations or religious. They were, indeed, as if they had had no warning, no expectation, no apprehensions, and consequently the least provision imaginable was made for it in a public way. For example, the Lord Mayor and sheriffs had made no provision as magistrates for the regulations which were to be observed. They had gone into no measures for relief of the poor. The citizens had no public magazines or storehouses for corn or meal for the subsistence of the poor, which if they had provided themselves, as in such cases is done abroad, many miserable families who were now reduced to the utmost distress would have been relieved, and that in a better manner than now could be done.

The stock of the city's money I can say but little to. The Chamber of London was said to be exceedingly rich, and it may be concluded that they were so, by the vast of money issued from thence in the rebuilding the public edifices after the fire of London, and in building new works, such as, for the first part, the Guildhall, Blackwell Hall, part of Leadenhall, half the Exchange, the Session House, the Compter, the prisons of Ludgate, Newgate, &c., several of the wharfs and stairs and landing-places on the river; all which were either burned down or damaged by the great fire of London, the next year after the plague; and of the second sort, the Monument, Fleet Ditch with its bridges, and the Hospital of Bethlem or Bedlam, &c. But possibly the managers of the city's credit at that time made more conscience of breaking in upon the orphan's money to show charity to the distressed citizens than the managers in the following years did to beautify the city and re-edify the buildings; though, in the first case, the losers would have thought their fortunes better bestowed, and the public faith of the city have been less subjected to scandal and reproach.

It must be acknowledged that the absent citizens, who, though they were fled for safety into the country, were yet greatly interested in the welfare of those whom they left behind, forgot not to contribute liberally to the relief of the poor, and large sums were also collected among trading towns in the remotest parts of England; and, as I have heard also, the nobility and the gentry in all parts of England took the deplorable condition of the city into their consideration, and sent up large sums of money in charity to the Lord Mayor and magistrates for the relief of the poor. The king also, as I was told, ordered a thousand pounds a week to be distributed in four parts: one quarter to the city and liberty of Westminster; one quarter or part among the inhabitants of the Southwark side of the water; one quarter to the liberty and parts within of the city, exclusive of the city within the walls; and one-fourth part to the suburbs in the county of Middlesex, and the east and north parts of the city. But this latter I only speak of as a report.

Certain it is, the greatest part of the poor or families who formerly lived by their labour, or by retail trade, lived now on charity; and had there not been prodigious sums of money given by charitable, well-minded Christians for the support of such, the city could never have subsisted. There were, no question, accounts kept of their charity, and of the just distribution of it by the magistrates. But as such multitudes of those very officers died through whose hands it was distributed, and also that, as I have been told, most of the accounts of those things were lost in the great fire which happened in the very next year, and which burnt even the chamberlain's office and many of their papers, so I could never come at the particular account, which I used great endeavours to have seen.

It may, however, be a direction in case of the approach of a like visitation, which God keep the city from; – I say, it may be of use to observe that by the care of the Lord Mayor and aldermen at that time in distributing weekly great sums of money for relief of the poor, a multitude of people who would otherwise have perished, were relieved, and their lives preserved. And here let me enter into a brief state of the case of the poor at that time, and what way apprehended from them, from whence may be judged hereafter what may be expected if the like distress should come upon the city.

At the beginning of the plague, when there was now no more hope but that the whole city would be visited; when, as I have said, all that had friends or estates in the country retired with their families; and when, indeed, one would have thought the very city itself was running out of the gates, and that there would be nobody left behind; you may be sure from that hour all trade, except such as related to immediate subsistence, was, as it were, at a full stop.

This is so lively a case, and contains in it so much of the real condition of the people, that I think I cannot be too particular in it, and therefore I descend to the several arrangements or classes of people who fell into immediate distress upon this occasion. For example:

1. All master-workmen in manufactures, especially such as belonged to ornament and the less necessary parts of the people's dress, clothes, and furniture for houses, such as riband-weavers and other weavers, gold and silver lace makers, and gold and silver wire drawers, sempstresses, milliners, shoemakers, hatmakers, and glovemakers; also upholsterers, joiners, cabinet-makers, looking-glass makers, and innumerable trades which depend upon such as these; – I say, the master-workmen in such stopped their work, dismissed their journeymen and workmen, and all their dependents.

2. As merchandising was at a full stop, for very few ships ventured to come up the river and none at all went out, so all the extraordinary officers of the customs, likewise the watermen, carmen, porters, and all the poor whose labour depended upon the merchants, were at once dismissed and put out of business.

3. All the tradesmen usually employed in building or repairing of houses were at a full stop, for the people were far from wanting to build houses when so many thousand houses were at once stripped of their inhabitants; so that this one article turned all the ordinary workmen of that kind out of business, such as bricklayers, masons, carpenters, joiners, plasterers, painters, glaziers, smiths, plumbers, and all the labourers depending on such.

4. As navigation was at a stop, our ships neither coming in or going out as before, so the seamen were all out of employment, and many of them in the last and lowest degree of distress; and with the seamen were all the several tradesmen and workmen belonging to and depending upon the building and fitting out of ships, such as ship-carpenters, caulkers, ropemakers, dry coopers, sailmakers, anchorsmiths, and other smiths; blockmakers, carvers, gunsmiths, ship-chandlers, ship-carvers, and the like. The masters of those perhaps might live upon their substance, but the traders were universally at a stop, and consequently all their workmen discharged. Add to these that the river was in a manner without boats, and all or most part of the watermen, lightermen, boat-builders, and lighter-builders in like manner idle and laid by.

5. All families retrenched their living as much as possible, as well those that fled as those that stayed; so that an innumerable multitude of footmen, serving-men, shopkeepers, journeymen, merchants' bookkeepers, and such sort of people, and especially poor maid-servants, were turned off, and left friendless and helpless, without employment and without habitation, and this was really a dismal article.

I might be more particular as to this part, but it may suffice to mention in general, all trades being stopped, employment ceased: the labour, and by that the bread, of the poor were cut off; and at first indeed the cries of the poor were most lamentable to hear, though by the distribution of charity their misery that way was greatly abated. Many indeed fled into the counties, but thousands of them having stayed in London till nothing but desperation sent them away, death overtook them on the road, and they served for no better than the messengers of death; indeed, others carrying the infection along with them, spread it very unhappily into the remotest parts of the kingdom.

Many of these were the miserable objects of despair which I have mentioned before, and were removed by the destruction which followed. These might be said to perish not by the infection itself but by the consequence of it; indeed, namely, by hunger and distress and the want of all things: being without lodging, without money, without friends, without means to get their bread, or without anyone to give it them; for many of them were without what we call legal settlements, and so could not claim of the parishes, and all the support they had was by application to the magistrates for relief, which relief was (to give the magistrates their due) carefully and cheerfully administered as they found it necessary, and those that stayed behind never felt the want and distress of that kind which they felt who went away in the manner above noted.

Let any one who is acquainted with what multitudes of people get their daily bread in this city by their labour, whether artificers or mere workmen – I say, let any man consider what must be the miserable condition of this town if, on a sudden, they should be all turned out of employment, that labour should cease, and wages for work be no more.

This was the case with us at that time; and had not the sums of money contributed in charity by well-disposed people of every kind, as well abroad as at home, been prodigiously great, it had not been in the power of the Lord Mayor and sheriffs to have kept the public peace. Nor were they without apprehensions, as it was, that desperation should push the people upon tumults, and cause them to rifle the houses of rich men and plunder the markets of provisions; in which case the country people, who brought provisions very freely and boldly to town, would have been terrified from coming any more, and the town would have sunk under an unavoidable famine.

But the prudence of my Lord Mayor and the Court of Aldermen within the city, and of the justices of peace in the out-parts, was such, and they were supported with money from all parts so well, that the poor people were kept quiet, and their wants everywhere relieved, as far as was possible to be done.

Two things besides this contributed to prevent the mob doing any mischief. One was, that really the rich themselves had not laid up stores of provisions in their houses as indeed they ought to have done, and which if they had been wise enough to have done, and locked themselves entirely up, as some few did, they had perhaps escaped the disease better. But as it appeared they had not, so the mob had no notion of finding stores of provisions there if they had broken in as it is plain they were sometimes very near doing, and which: if they had, they had finished the ruin of the whole city, for there were no regular troops to have withstood them, nor could the trained bands have been brought together to defend the city, no men being to be found to bear arms.

But the vigilance of the Lord Mayor and such magistrates as could be had (for some, even of the aldermen, were dead, and some absent) prevented this; and they did it by the most kind and gentle methods they could think of, as particularly by relieving the most desperate with money, and putting others into business, and particularly that employment of watching houses that were infected and shut up. And as the number of these were very great (for it was said there was at one time ten thousand houses shut up, and every house had two watchmen to guard it, viz., one by night and the other by day), this gave opportunity to employ a very great number of poor men at a time.

The women and servants that were turned off from their places were likewise employed as nurses to tend the sick in all places, and this took off a very great number of them.

And, which though a melancholy article in itself, yet was a deliverance in its kind: namely, the plague, which raged in a dreadful manner from the middle of August to the middle of October, carried off in that time thirty or forty thousand of these very people which, had they been left, would certainly have been an insufferable burden by their poverty; that is to say, the whole city could not have supported the expense of them, or have provided food for them; and they would in time have been even driven to the necessity of plundering either the city itself or the country adjacent, to have subsisted themselves, which would first or last have put the whole nation, as well as the city, into the utmost terror and confusion.

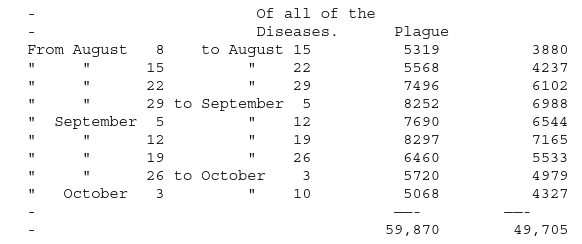

It was observable, then, that this calamity of the people made them very humble; for now for about nine weeks together there died near a thousand a day, one day with another, even by the account of the weekly bills, which yet, I have reason to be assured, never gave a full account, by many thousands; the confusion being such, and the carts working in the dark when they carried the dead, that in some places no account at all was kept, but they worked on, the clerks and sextons not attending for weeks together, and not knowing what number they carried. This account is verified by the following bills of mortality: —

So that the gross of the people were carried off in these two months; for, as the whole number which was brought in to die of the plague was but 68,590, here is 50,000 of them, within a trifle, in two months; I say 50,000, because, as there wants 295 in the number above, so there wants two days of two months in the account of time.

Now when I say that the parish officers did not give in a full account, or were not to be depended upon for their account, let any one but consider how men could be exact in such a time of dreadful distress, and when many of them were taken sick themselves and perhaps died in the very time when their accounts were to be given in; I mean the parish clerks, besides inferior officers; for though these poor men ventured at all hazards, yet they were far from being exempt from the common calamity, especially if it be true that the parish of Stepney had, within the year, 116 sextons, gravediggers, and their assistants; that is to say, bearers, bellmen, and drivers of carts for carrying off the dead bodies.

Indeed the work was not of a nature to allow them leisure to take an exact tale of the dead bodies, which were all huddled together in the dark into a pit; which pit or trench no man could come nigh but at the utmost peril. I observed often that in the parishes of Aldgate and Cripplegate, Whitechappel and Stepney, there were five, six, seven, and eight hundred in a week in the bills; whereas if we may believe the opinion of those that lived in the city all the time as well as I, there died sometimes 2000 a week in those parishes; and I saw it under the hand of one that made as strict an examination into that part as he could, that there really died an hundred thousand people of the plague in that one year whereas in the bills, the articles of the plague, it was but 68,590.

If I may be allowed to give my opinion, by what I saw with my eyes and heard from other people that were eye-witnesses, I do verily believe the same, viz., that there died at least 100,000 of the plague only, besides other distempers and besides those which died in the fields and highways and secret Places out of the compass of the communication, as it was called, and who were not put down in the bills though they really belonged to the body of the inhabitants. It was known to us all that abundance of poor despairing creatures who had the distemper upon them, and were grown stupid or melancholy by their misery, as many were, wandered away into the fields and Woods, and into secret uncouth places almost anywhere, to creep into a bush or hedge and die.