Полная версия

Полная версияПолная версия:

A Journal of the Plague Year

I cannot guess at the number of ships, but I think there must be several hundreds of sail; and I could not but applaud the contrivance: for ten thousand people and more who attended ship affairs were certainly sheltered here from the violence of the contagion, and lived very safe and very easy.

I returned to my own dwelling very well satisfied with my day's journey, and particularly with the poor man; also I rejoiced to see that such little sanctuaries were provided for so many families in a time of such desolation. I observed also that, as the violence of the plague had increased, so the ships which had families on board removed and went farther off, till, as I was told, some went quite away to sea, and put into such harbours and safe roads on the north coast as they could best come at.

But it was also true that all the people who thus left the land and lived on board the ships were not entirely safe from the infection, for many died and were thrown overboard into the river, some in coffins, and some, as I heard, without coffins, whose bodies were seen sometimes to drive up and down with the tide in the river.

But I believe I may venture to say that in those ships which were thus infected it either happened where the people had recourse to them too late, and did not fly to the ship till they had stayed too long on shore and had the distemper upon them (though perhaps they might not perceive it) and so the distemper did not come to them on board the ships, but they really carried it with them; or it was in these ships where the poor waterman said they had not had time to furnish themselves with provisions, but were obliged to send often on shore to buy what they had occasion for, or suffered boats to come to them from the shore. And so the distemper was brought insensibly among them.

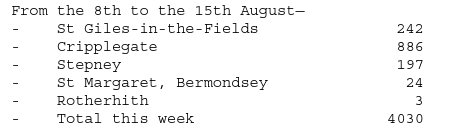

And here I cannot but take notice that the strange temper of the people of London at that time contributed extremely to their own destruction. The plague began, as I have observed, at the other end of the town, namely, in Long Acre, Drury Lane, &c., and came on towards the city very gradually and slowly. It was felt at first in December, then again in February, then again in April, and always but a very little at a time; then it stopped till May, and even the last week in May there was but seventeen, and all at that end of the town; and all this while, even so long as till there died above 3000 a week, yet had the people in Redriff, and in Wapping and Ratcliff, on both sides of the river, and almost all Southwark side, a mighty fancy that they should not be visited, or at least that it would not be so violent among them. Some people fancied the smell of the pitch and tar, and such other things as oil and rosin and brimstone, which is so much used by all trades relating to shipping, would preserve them. Others argued it, because it was in its extreamest violence in Westminster and the parish of St Giles and St Andrew, &c., and began to abate again before it came among them – which was true indeed, in part. For example —

N.B. – That it was observed the numbers mentioned in Stepney parish at that time were generally all on that side where Stepney parish joined to Shoreditch, which we now call Spittlefields, where the parish of Stepney comes up to the very wall of Shoreditch Churchyard, and the plague at this time was abated at St Giles-in-the-Fields, and raged most violently in Cripplegate, Bishopsgate, and Shoreditch parishes; but there was not ten people a week that died of it in all that part of Stepney parish which takes in Limehouse, Ratdiff Highway, and which are now the parishes of Shadwell and Wapping, even to St Katherine's by the Tower, till after the whole month of August was expired. But they paid for it afterwards, as I shall observe by-and-by.

This, I say, made the people of Redriff and Wapping, Ratcliff and Limehouse, so secure, and flatter themselves so much with the plague's going off without reaching them, that they took no care either to fly into the country or shut themselves up. Nay, so far were they from stirring that they rather received their friends and relations from the city into their houses, and several from other places really took sanctuary in that part of the town as a Place of safety, and as a place which they thought God would pass over, and not visit as the rest was visited.

And this was the reason that when it came upon them they were more surprised, more unprovided, and more at a loss what to do than they were in other places; for when it came among them really and with violence, as it did indeed in September and October, there was then no stirring out into the country, nobody would suffer a stranger to come near them, no, nor near the towns where they dwelt; and, as I have been told, several that wandered into the country on Surrey side were found starved to death in the woods and commons, that country being more open and more woody than any other part so near London, especially about Norwood and the parishes of Camberwell, Dullege, and Lusum, where, it seems, nobody durst relieve the poor distressed people for fear of the infection.

This notion having, as I said, prevailed with the people in that part of the town, was in part the occasion, as I said before, that they had recourse to ships for their retreat; and where they did this early and with prudence, furnishing themselves so with provisions that they had no need to go on shore for supplies or suffer boats to come on board to bring them, – I say, where they did so they had certainly the safest retreat of any people whatsoever; but the distress was such that people ran on board, in their fright, without bread to eat, and some into ships that had no men on board to remove them farther off, or to take the boat and go down the river to buy provisions where it might be done safely, and these often suffered and were infected on board as much as on shore.

As the richer sort got into ships, so the lower rank got into hoys, smacks, lighters, and fishing-boats; and many, especially watermen, lay in their boats; but those made sad work of it, especially the latter, for, going about for provision, and perhaps to get their subsistence, the infection got in among them and made a fearful havoc; many of the watermen died alone in their wherries as they rid at their roads, as well as above bridge as below, and were not found sometimes till they were not in condition for anybody to touch or come near them.

Indeed, the distress of the people at this seafaring end of the town was very deplorable, and deserved the greatest commiseration. But, alas! this was a time when every one's private safety lay so near them that they had no room to pity the distresses of others; for every one had death, as it were, at his door, and many even in their families, and knew not what to do or whither to fly.

This, I say, took away all compassion; self-preservation, indeed, appeared here to be the first law. For the children ran away from their parents as they languished in the utmost distress. And in some places, though not so frequent as the other, parents did the like to their children; nay, some dreadful examples there were, and particularly two in one week, of distressed mothers, raving and distracted, killing their own children; one whereof was not far off from where I dwelt, the poor lunatic creature not living herself long enough to be sensible of the sin of what she had done, much less to be punished for it.

It is not, indeed, to be wondered at: for the danger of immediate death to ourselves took away all bowels of love, all concern for one another. I speak in general, for there were many instances of immovable affection, pity, and duty in many, and some that came to my knowledge, that is to say, by hearsay; for I shall not take upon me to vouch the truth of the particulars.

To introduce one, let me first mention that one of the most deplorable cases in all the present calamity was that of women with child, who, when they came to the hour of their sorrows, and their pains come upon them, could neither have help of one kind or another; neither midwife or neighbouring women to come near them. Most of the midwives were dead, especially of such as served the poor; and many, if not all the midwives of note, were fled into the country; so that it was next to impossible for a poor woman that could not pay an immoderate price to get any midwife to come to her – and if they did, those they could get were generally unskilful and ignorant creatures; and the consequence of this was that a most unusual and incredible number of women were reduced to the utmost distress. Some were delivered and spoiled by the rashness and ignorance of those who pretended to lay them. Children without number were, I might say, murdered by the same but a more justifiable ignorance: pretending they would save the mother, whatever became of the child; and many times both mother and child were lost in the same manner; and especially where the mother had the distemper, there nobody would come near them and both sometimes perished. Sometimes the mother has died of the plague, and the infant, it may be, half born, or born but not parted from the mother. Some died in the very pains of their travail, and not delivered at all; and so many were the cases of this kind that it is hard to judge of them.

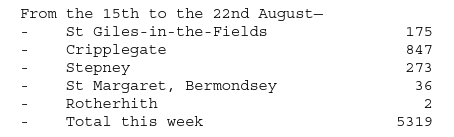

Something of it will appear in the unusual numbers which are put into the weekly bills (though I am far from allowing them to be able to give anything of a full account) under the articles of —

Child-bed.

Abortive and Still-born.

Christmas and Infants.

Take the weeks in which the plague was most violent, and compare them with the weeks before the distemper began, even in the same year. For example: —

To the disparity of these numbers it is to be considered and allowed for, that according to our usual opinion who were then upon the spot, there were not one-third of the people in the town during the months of August and September as were in the months of January and February. In a word, the usual number that used to die of these three articles, and, as I hear, did die of them the year before, was thus: —

This inequality, I say, is exceedingly augmented when the numbers of people are considered. I pretend not to make any exact calculation of the numbers of people which were at this time in the city, but I shall make a probable conjecture at that part by-and-by. What I have said now is to explain the misery of those poor creatures above; so that it might well be said, as in the Scripture, Woe be to those who are with child, and to those which give suck in that day. For, indeed, it was a woe to them in particular.

I was not conversant in many particular families where these things happened, but the outcries of the miserable were heard afar off. As to those who were with child, we have seen some calculation made; 291 women dead in child-bed in nine weeks, out of one-third part of the number of whom there usually died in that time but eighty-four of the same disaster. Let the reader calculate the proportion.

There is no room to doubt but the misery of those that gave suck was in proportion as great. Our bills of mortality could give but little light in this, yet some it did. There were several more than usual starved at nurse, but this was nothing. The misery was where they were, first, starved for want of a nurse, the mother dying and all the family and the infants found dead by them, merely for want; and, if I may speak my opinion, I do believe that many hundreds of poor helpless infants perished in this manner. Secondly, not starved, but poisoned by the nurse. Nay, even where the mother has been nurse, and having received the infection, has poisoned, that is, infected the infant with her milk even before they knew they were infected themselves; nay, and the infant has died in such a case before the mother. I cannot but remember to leave this admonition upon record, if ever such another dreadful visitation should happen in this city, that all women that are with child or that give suck should be gone, if they have any possible means, out of the place, because their misery, if infected, will so much exceed all other people's.

I could tell here dismal stories of living infants being found sucking the breasts of their mothers, or nurses, after they have been dead of the plague. Of a mother in the parish where I lived, who, having a child that was not well, sent for an apothecary to view the child; and when he came, as the relation goes, was giving the child suck at her breast, and to all appearance was herself very well; but when the apothecary came close to her he saw the tokens upon that breast with which she was suckling the child. He was surprised enough, to be sure, but, not willing to fright the poor woman too much, he desired she would give the child into his hand; so he takes the child, and going to a cradle in the room, lays it in, and opening its cloths, found the tokens upon the child too, and both died before he could get home to send a preventive medicine to the father of the child, to whom he had told their condition. Whether the child infected the nurse-mother or the mother the child was not certain, but the last most likely. Likewise of a child brought home to the parents from a nurse that had died of the plague, yet the tender mother would not refuse to take in her child, and laid it in her bosom, by which she was infected; and died with the child in her arms dead also.

It would make the hardest heart move at the instances that were frequently found of tender mothers tending and watching with their dear children, and even dying before them, and sometimes taking the distemper from them and dying, when the child for whom the affectionate heart had been sacrificed has got over it and escaped.

The like of a tradesman in East Smithfield, whose wife was big with child of her first child, and fell in labour, having the plague upon her. He could neither get midwife to assist her or nurse to tend her, and two servants which he kept fled both from her. He ran from house to house like one distracted, but could get no help; the utmost he could get was, that a watchman, who attended at an infected house shut up, promised to send a nurse in the morning. The poor man, with his heart broke, went back, assisted his wife what he could, acted the part of the midwife, brought the child dead into the world, and his wife in about an hour died in his arms, where he held her dead body fast till the morning, when the watchman came and brought the nurse as he had promised; and coming up the stairs (for he had left the door open, or only latched), they found the man sitting with his dead wife in his arms, and so overwhelmed with grief that he died in a few hours after without any sign of the infection upon him, but merely sunk under the weight of his grief.

I have heard also of some who, on the death of their relations, have grown stupid with the insupportable sorrow; and of one, in particular, who was so absolutely overcome with the pressure upon his spirits that by degrees his head sank into his body, so between his shoulders that the crown of his head was very little seen above the bone of his shoulders; and by degrees losing both voice and sense, his face, looking forward, lay against his collarbone and could not be kept up any otherwise, unless held up by the hands of other people; and the poor man never came to himself again, but languished near a year in that condition, and died. Nor was he ever once seen to lift up his eyes or to look upon any particular object.

I cannot undertake to give any other than a summary of such passages as these, because it was not possible to come at the particulars, where sometimes the whole families where such things happened were carried off by the distemper. But there were innumerable cases of this kind which presented to the eye and the ear, even in passing along the streets, as I have hinted above. Nor is it easy to give any story of this or that family which there was not divers parallel stories to be met with of the same kind.

But as I am now talking of the time when the plague raged at the easternmost part of the town – how for a long time the people of those parts had flattered themselves that they should escape, and how they were surprised when it came upon them as it did; for, indeed, it came upon them like an armed man when it did come; – I say, this brings me back to the three poor men who wandered from Wapping, not knowing whither to go or what to do, and whom I mentioned before; one a biscuit-baker, one a sailmaker, and the other a joiner, all of Wapping, or there-abouts.

The sleepiness and security of that part, as I have observed, was such that they not only did not shift for themselves as others did, but they boasted of being safe, and of safety being with them; and many people fled out of the city, and out of the infected suburbs, to Wapping, Ratcliff, Limehouse, Poplar, and such Places, as to Places of security; and it is not at all unlikely that their doing this helped to bring the plague that way faster than it might otherwise have come. For though I am much for people flying away and emptying such a town as this upon the first appearance of a like visitation, and that all people who have any possible retreat should make use of it in time and be gone, yet I must say, when all that will fly are gone, those that are left and must stand it should stand stock-still where they are, and not shift from one end of the town or one part of the town to the other; for that is the bane and mischief of the whole, and they carry the plague from house to house in their very clothes.

Wherefore were we ordered to kill all the dogs and cats, but because as they were domestic animals, and are apt to run from house to house and from street to street, so they are capable of carrying the effluvia or infectious streams of bodies infected even in their furs and hair? And therefore it was that, in the beginning of the infection, an order was published by the Lord Mayor, and by the magistrates, according to the advice of the physicians, that all the dogs and cats should be immediately killed, and an officer was appointed for the execution.

It is incredible, if their account is to be depended upon, what a prodigious number of those creatures were destroyed. I think they talked of forty thousand dogs, and five times as many cats; few houses being without a cat, some having several, sometimes five or six in a house. All possible endeavours were used also to destroy the mice and rats, especially the latter, by laying ratsbane and other poisons for them, and a prodigious multitude of them were also destroyed.

I often reflected upon the unprovided condition that the whole body of the people were in at the first coming of this calamity upon them, and how it was for want of timely entering into measures and managements, as well public as private, that all the confusions that followed were brought upon us, and that such a prodigious number of people sank in that disaster, which, if proper steps had been taken, might, Providence concurring, have been avoided, and which, if posterity think fit, they may take a caution and warning from. But I shall come to this part again.

I come back to my three men. Their story has a moral in every part of it, and their whole conduct, and that of some whom they joined with, is a pattern for all poor men to follow, or women either, if ever such a time comes again; and if there was no other end in recording it, I think this a very just one, whether my account be exactly according to fact or no.

Two of them are said to be brothers, the one an old soldier, but now a biscuit-maker; the other a lame sailor, but now a sailmaker; the third a joiner. Says John the biscuit-maker one day to Thomas his brother, the sailmaker, 'Brother Tom, what will become of us? The plague grows hot in the city, and increases this way. What shall we do?'

'Truly,' says Thomas, 'I am at a great loss what to do, for I find if it comes down into Wapping I shall be turned out of my lodging.' And thus they began to talk of it beforehand.

John. Turned out of your lodging, Tom! If you are, I don't know who will take you in; for people are so afraid of one another now, there's no getting a lodging anywhere.

Thomas. Why, the people where I lodge are good, civil people, and have kindness enough for me too; but they say I go abroad every day to my work, and it will be dangerous; and they talk of locking themselves up and letting nobody come near them.

John. Why, they are in the right, to be sure, if they resolve to venture staying in town.

Thomas. Nay, I might even resolve to stay within doors too, for, except a suit of sails that my master has in hand, and which I am just finishing, I am like to get no more work a great while. There's no trade stirs now. Workmen and servants are turned off everywhere, so that I might be glad to be locked up too; but I do not see they will be willing to consent to that, any more than to the other.

John. Why, what will you do then, brother? And what shall I do? for I am almost as bad as you. The people where I lodge are all gone into the country but a maid, and she is to go next week, and to shut the house quite up, so that I shall be turned adrift to the wide world before you, and I am resolved to go away too, if I knew but where to go.

Thomas. We were both distracted we did not go away at first; then we might have travelled anywhere. There's no stirring now; we shall be starved if we pretend to go out of town. They won't let us have victuals, no, not for our money, nor let us come into the towns, much less into their houses.

John. And that which is almost as bad, I have but little money to help myself with neither.

Thomas. As to that, we might make shift, I have a little, though not much; but I tell you there's no stirring on the road. I know a couple of poor honest men in our street have attempted to travel, and at Barnet, or Whetstone, or thereabouts, the people offered to fire at them if they pretended to go forward, so they are come back again quite discouraged.

John. I would have ventured their fire if I had been there. If I had been denied food for my money they should have seen me take it before their faces, and if I had tendered money for it they could not have taken any course with me by law.

Thomas. You talk your old soldier's language, as if you were in the Low Countries now, but this is a serious thing. The people have good reason to keep anybody off that they are not satisfied are sound, at such a time as this, and we must not plunder them.

John. No, brother, you mistake the case, and mistake me too. I would plunder nobody; but for any town upon the road to deny me leave to pass through the town in the open highway, and deny me provisions for my money, is to say the town has a right to starve me to death, which cannot be true.

Thomas. But they do not deny you liberty to go back again from whence you came, and therefore they do not starve you.

John. But the next town behind me will, by the same rule, deny me leave to go back, and so they do starve me between them. Besides, there is no law to prohibit my travelling wherever I will on the road.

Thomas. But there will be so much difficulty in disputing with them at every town on the road that it is not for poor men to do it or undertake it, at such a time as this is especially.

John. Why, brother, our condition at this rate is worse than anybody else's, for we can neither go away nor stay here. I am of the same mind with the lepers of Samaria: 'If we stay here we are sure to die', I mean especially as you and I are stated, without a dwelling-house of our own, and without lodging in anybody else's. There is no lying in the street at such a time as this; we had as good go into the dead-cart at once. Therefore I say, if we stay here we are sure to die, and if we go away we can but die; I am resolved to be gone.

Thomas. You will go away. Whither will you go, and what can you do? I would as willingly go away as you, if I knew whither. But we have no acquaintance, no friends. Here we were born, and here we must die.