Полная версия:

Gulls

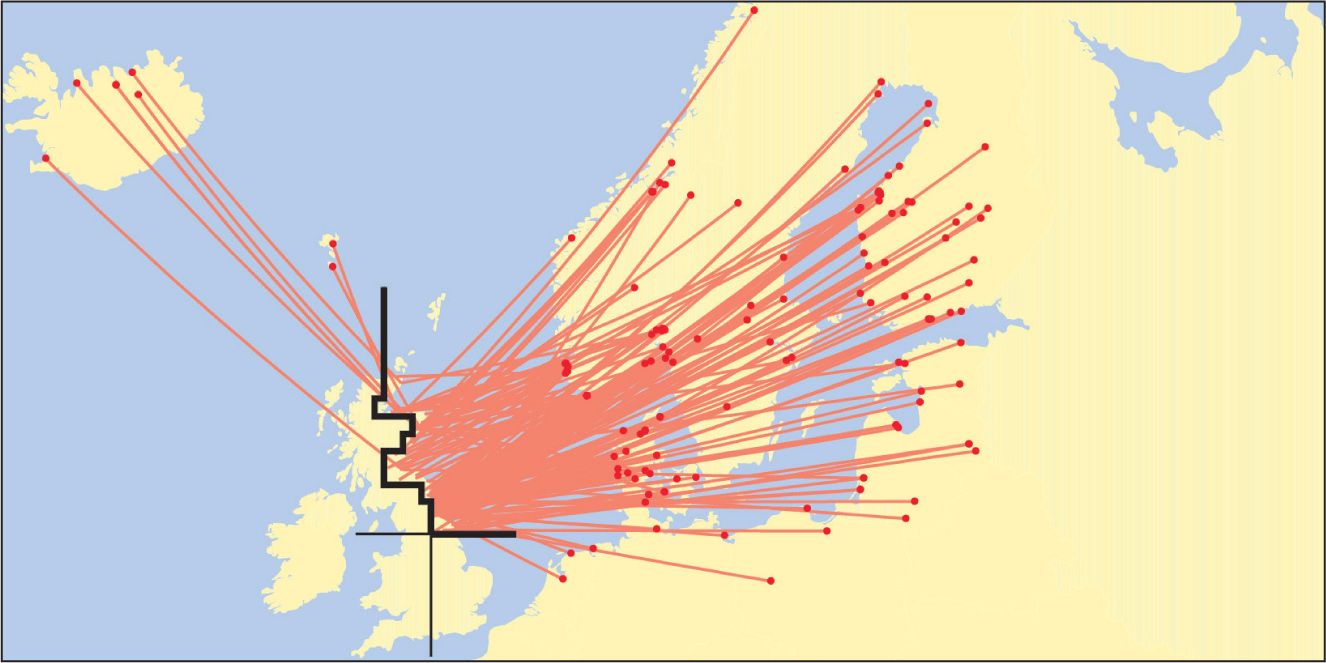

FIG 27. Black-headed Gulls ringed in winter in north-east Britain (to the right of the thick black line) and recovered abroad in a subsequent breeding season. Note the five Iceland recoveries. Reproduced from The Migration Atlas (Wernham et al. 2002), with permission from the BTO.

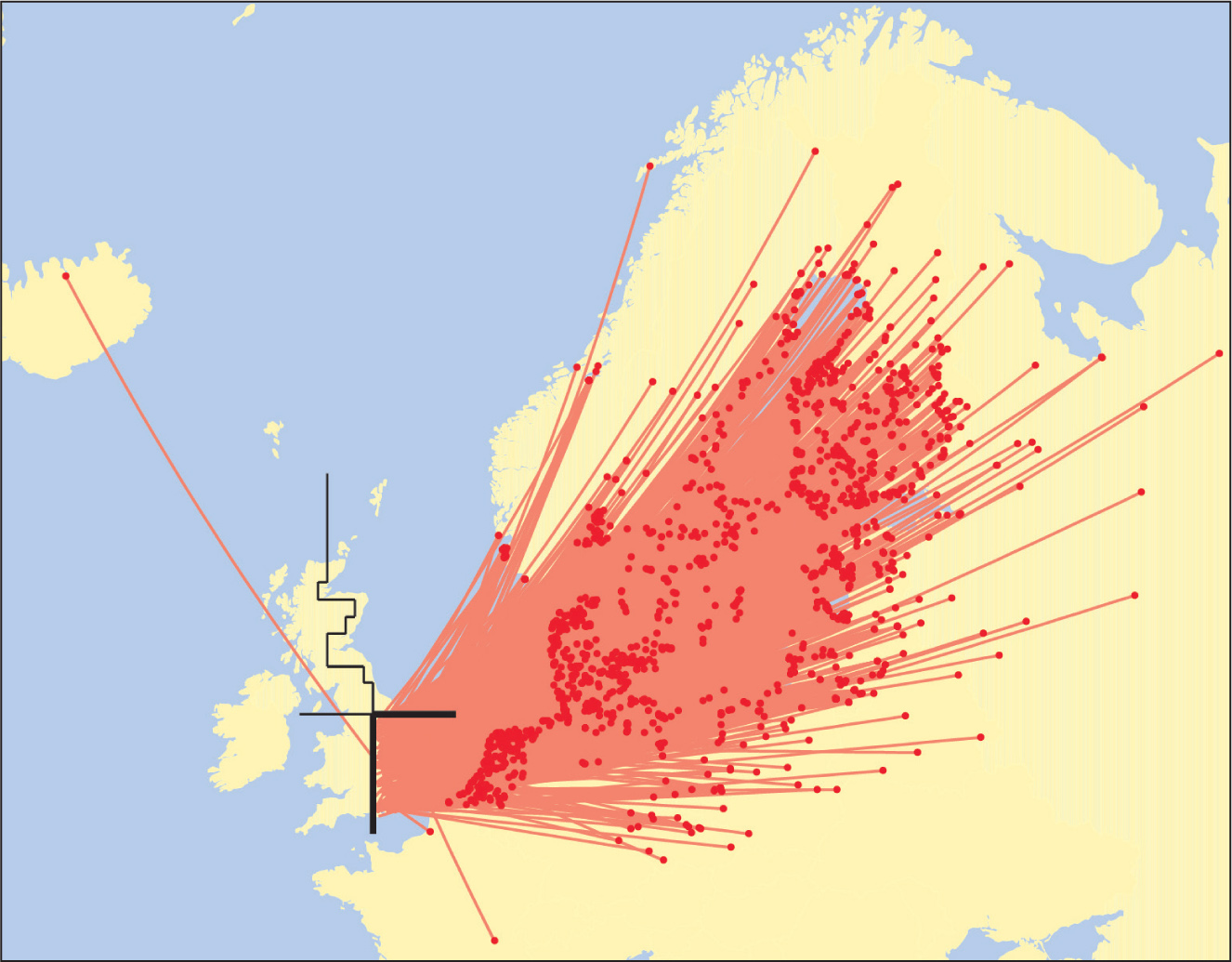

FIG 28. Black-headed Gulls ringed in winter in south-east Britain (to the right of the thick black line) and recovered abroad in a subsequent breeding season. Note the single Iceland recovery. Reproduced from The Migration Atlas (Wernham et al. 2002), with permission from the BTO.

FIG 29. Recoveries in Britain and Ireland of Black-headed Gulls ringed in mainland Europe expressed as a percentage of the monthly recoveries between December and February. Note the high proportion of birds entering their second year of life (which moult early) reported in Britain in July, and the late departure of first-year birds in spring, with a few apparently remaining in Britain during the summer.

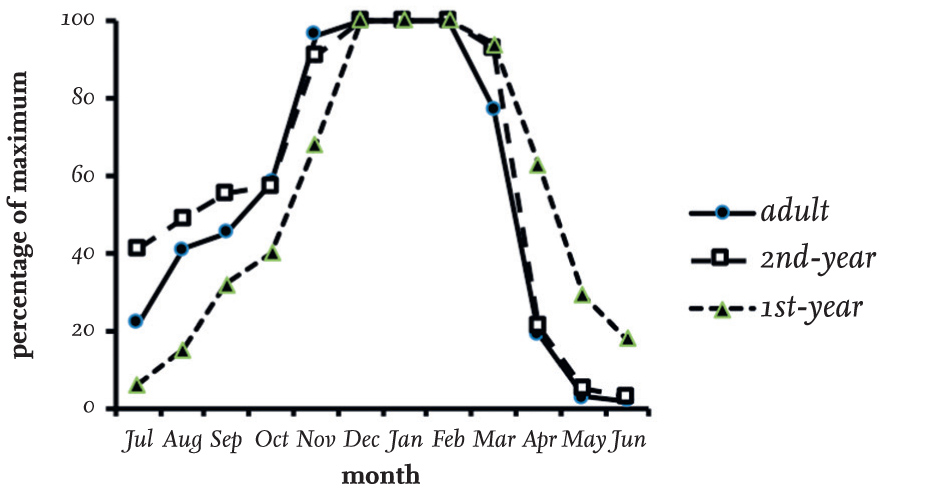

Numbers of all ages cross to Britain in August. By the end of that month, about half the adults that winter here have already arrived, but only 15 per cent of first-year birds have arrived. The early movement from countries bordering the Baltic Sea perhaps reflects the less favourable feeding conditions there. For example, the small tidal changes in the Baltic markedly restrict the extent of inter-tidal areas available for foraging, while the warmer and drier continental weather makes earthworms less available there in late summer.

There is evidence of a lag in new adult arrivals in Britain in September, probably because most adults are still completing their moult and growing their longest primaries. The lack of, or reduction of, these long feathers must impair their ability to make long flights. A second peak of arrival occurs in November, and by the end of that month most of the adults that winter here have arrived, apart from a few birds that possibly turn up in December. The maximum numbers of Black-headed Gulls are present in Britain for only three months, from December to late February.

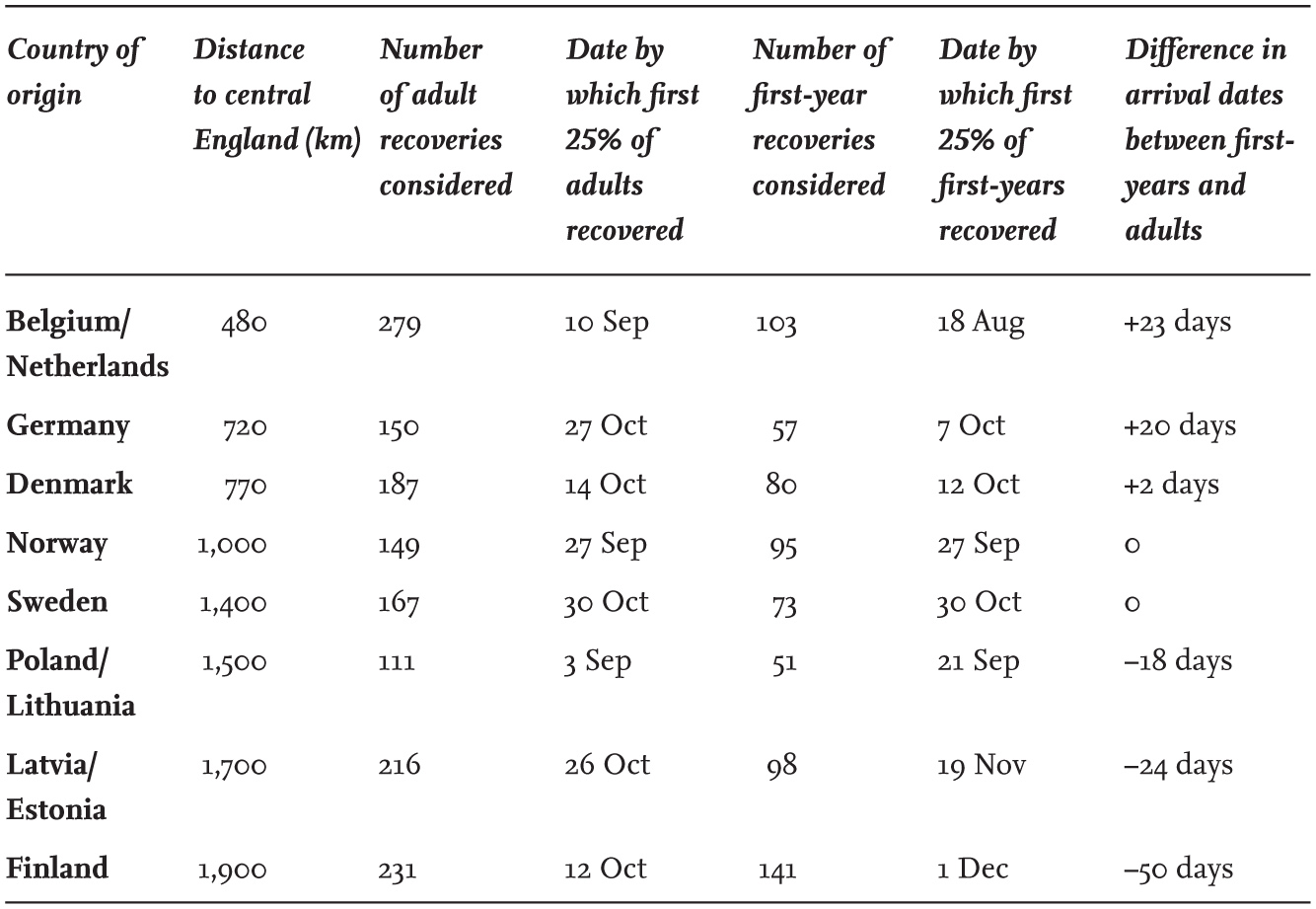

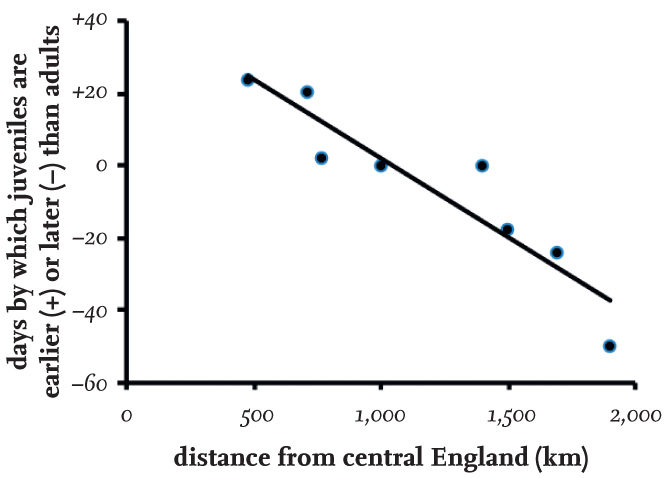

The timing of immigration of first-year and adult Black-headed Gulls in autumn to Britain depends on the country of origin. Dates after 1 July by which the first 25 per cent of recoveries of young birds and adults from abroad are recovered have been used as an index of the arrival times of first-year and adult Black-headed Gulls from different countries in Europe (Table 11). In general, adults and young birds arrive on different average dates, but this is not constant for each country of origin and varies by more than 60 days. Young birds arrive earlier than adults from countries closer to Britain, but the reverse applies for those from more distant countries. This suggests that first-year birds start their migration earlier than adults but move much slower, perhaps making a series of short journeys interspaced with stopovers at rest areas lasting a number of days. In contrast, adults appear to make much longer flights to their wintering area and arrive in Britain from European countries at less variable dates. The interpretation of the trend line in Fig. 30 suggests that first-year birds on migration take about 43 days longer than adults to travel 1,000 km.

TABLE 11. Date by which the first 25 per cent of adult and first-year Black-headed Gulls ringed abroad have been recovered in Britain in each 12-month period, starting 1 July. Based on MacKinnon and Coulson (1986).

FIG 30. Difference in the dates of the first 25 per cent of recoveries in Britain of first-year and adult Black-head Gulls of Continental origin (data from Table 8) in each 12 months from 1 July, plotted against the distance from country of origin to central England. Note that the first-year birds from countries close to England arrived earlier than the adults, but that the converse was true for those travelling further.

Faithfulness to wintering areas

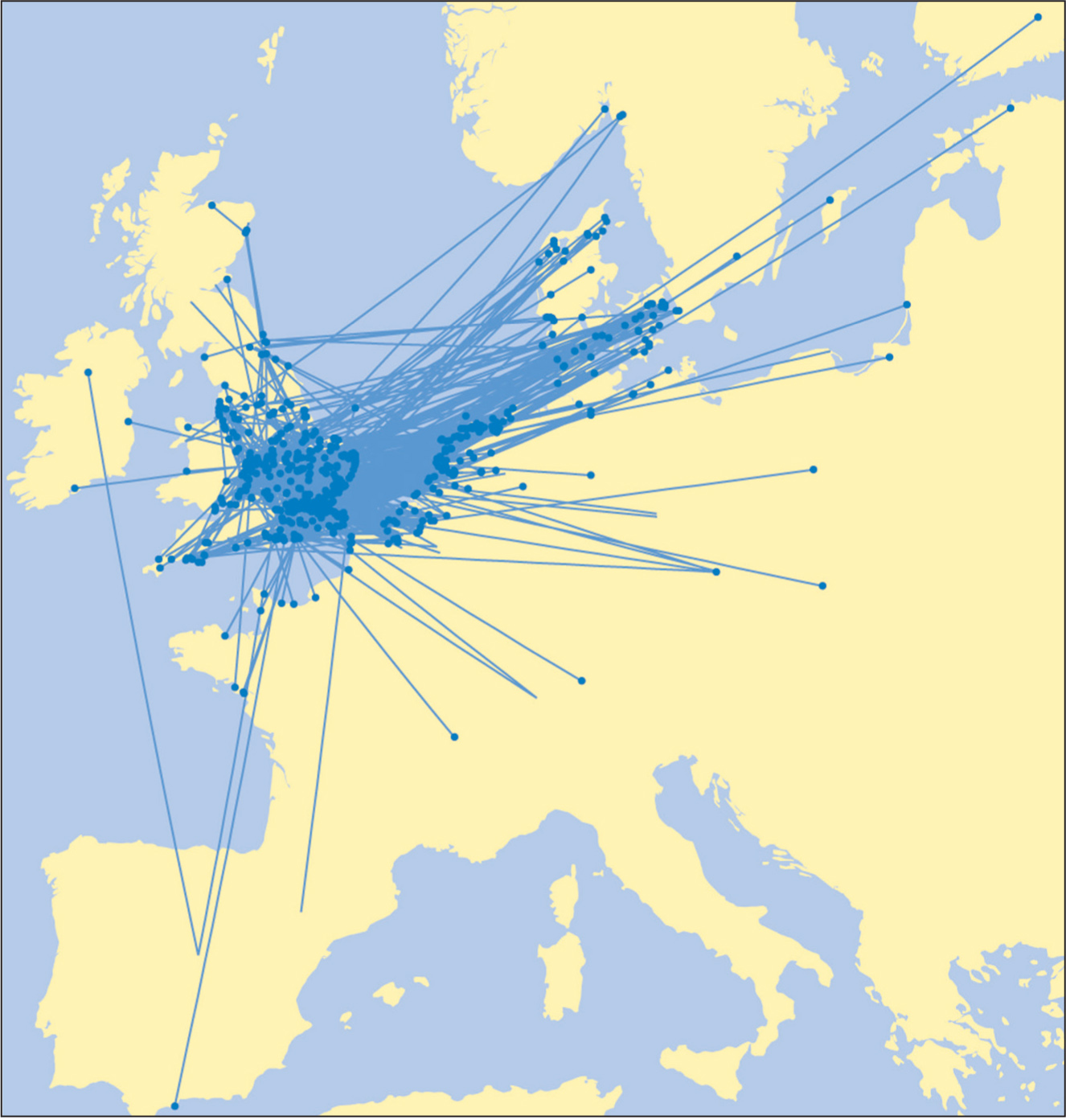

There is extensive and convincing evidence that some adult Black-headed Gulls from the Continent return to the same immediate wintering area year after year. The best example is a gull ringed in Poland, whose ring numbers were recorded in the same central London park over eight consecutive winters. However, such faithfulness to wintering areas is not absolute, as there are many instances of birds from the Continent wintering in Britain one year and then remaining in mainland Europe (usually in the Netherlands or Denmark) in the following winter (Fig. 31). It has been suggested, but not yet proven, that relatively mild conditions in western Europe in some recent winters have resulted in fewer Black-headed Gulls migrating here; this effect has also been reported for several species of waders and other waterbirds.

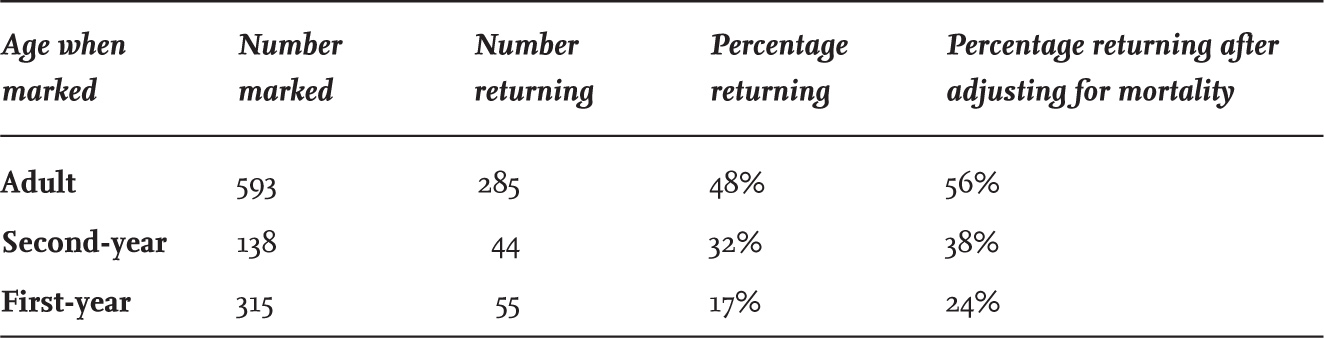

Evidence of the extent to which Black-headed Gulls use the same wintering area in successive years comes from individuals wing-tagged in north-east England, as these had a high probability of being seen if they returned in the following winter. Most tagged birds were breeding on the Continent, and so the annual return would involve many individuals migrating considerable distances. In the winter after tagging, those that returned were seen on an average of five different days, so it is unlikely that many others were missed. The study detected that 48 per cent of adults and 32 per cent of second-year birds, but only 17 per cent of first-year birds, returned to the same area in successive winters (Table 12). Allowing for mortality in the intervening year (estimated at about 15 per cent for adults and 30 per cent for first-year birds), 56 per cent of the surviving adults returned to the same wintering locality, with 38 per cent of those in their second winter when marked returning for a second time, but only 24 per cent of those marked in their first year.

FIG 31. Black-headed Gulls ringed in winter in Britain and recovered more than 20 km away in a subsequent winter. Many individuals returned to Britain, but note the appreciable number that failed to do so in a subsequent winter and were recovered on the Continent. Reproduced from The Migration Atlas (Wernham et al. 2002), with permission from the BTO.

TABLE 12. The proportions of marked Black-headed Gulls that returned to the same wintering area the following year.

A total of 38 marked individuals that did not return to the study areas were seen by other observers elsewhere in the winter following marking. These were reported mainly on the east coast of Britain, south of the study areas. Two extreme cases were recorded; one bird 450 km away on the south coast of England, and the other 300 km north at Aberdeen in Scotland. In addition, one remained in Denmark. It is evident from this that only a proportion of individuals of all age classes return to the same wintering area, but that faithfulness is stronger (although not complete) in adults. The reason why some birds return while others fail to do so remains unknown, but is not primarily related to their sex.

Return of birds to the Continent

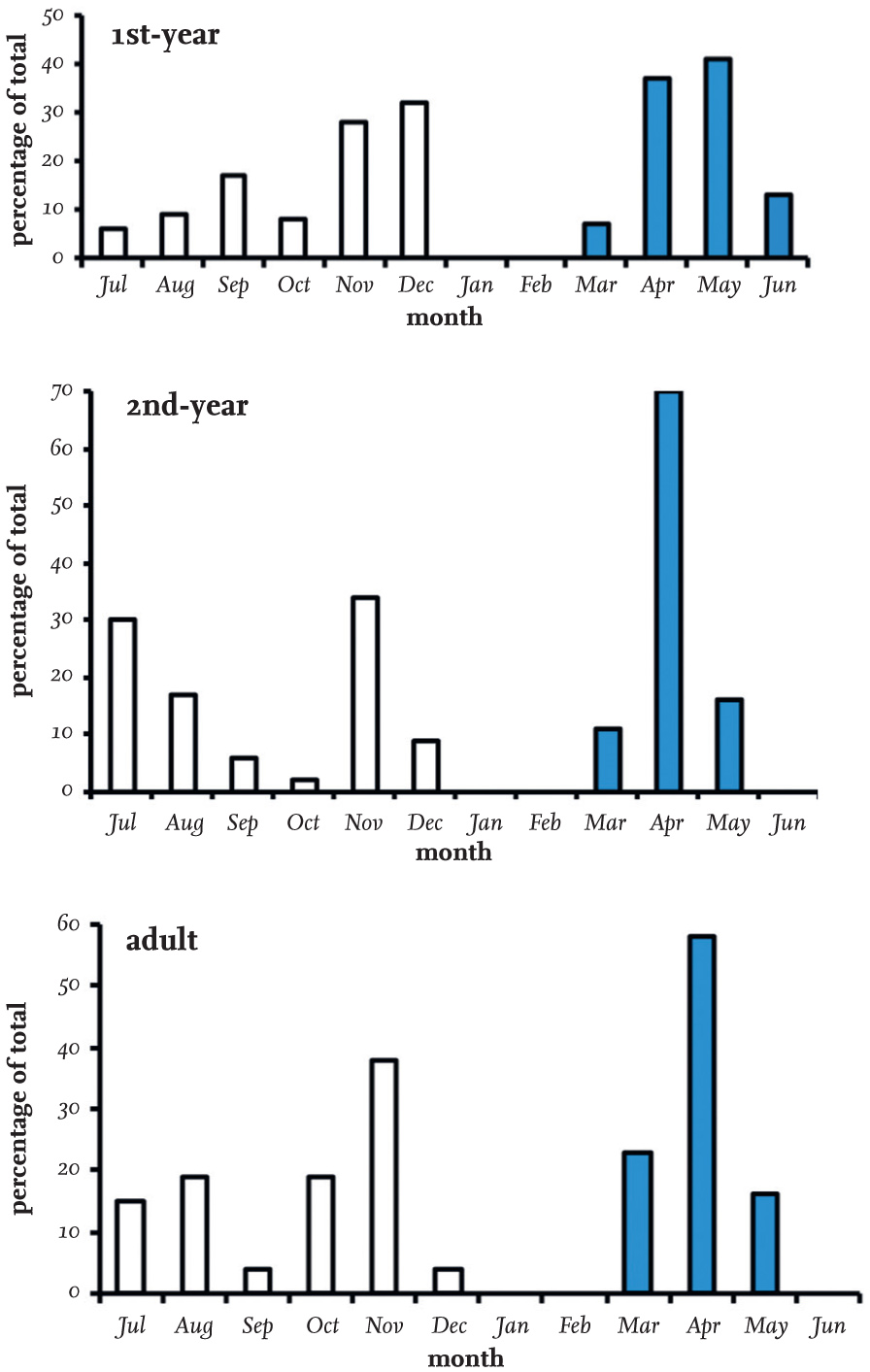

The return migration from Britain to the Continent is much more synchronised than the arrival and begins in late March, with most adults migrating in April (Fig. 32). First-year birds tend to depart later than adults and some do not leave until May, while others (perhaps 10 per cent of immature birds wintering here) remain throughout the summer. These birds join the feeding adults associated with colonies in Britain (since they leave their wintering feeding areas) and presumably do not return to the Continent until they have overwintered here for a second time.

FIG 32. The month of arrival of Black-headed Gulls entering Britain from the Continent in autumn (white bars) and leaving in spring (blue bars), based on monthly change in numbers of ringing recoveries of foreign birds in Britain. Note that for all age classes, the spring departure is much more synchronised than the autumn arrival dates.

By the end of July, numbers of second-years have arrived in Britain and joined the few that spent the summer here. These birds are not constrained by breeding and moult about four weeks earlier than adults, so this might explain their early crossing of the North Sea. More arrive in late October and early November, and many late arrivals originate from further away, east of the Baltic.

Distribution of Continental wintering birds

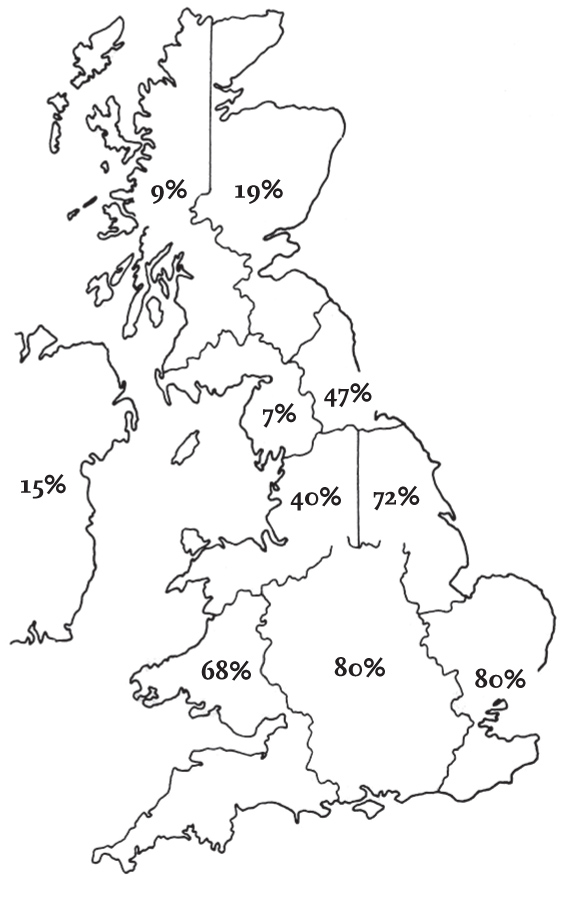

The Continental Black-headed Gulls that winter in Britain do not disperse randomly across the country, and are much more abundant in eastern and southern regions. The proportions of young gulls ringed in Britain or on the Continent and recovered from December to February in each of 10 regions of Britain and Ireland (4,267 recoveries in total) were used to produce an index of the proportions of geographical distribution in each area (Fig. 33). The percentages of Continental birds in these different regions ranged from 7 per cent to 80 per cent, based on at least 115 recoveries in each region and, in most cases, many more. The wide range of percentages obtained suggests that they are a close approximation to the actual proportions of birds of Continental origin. Ireland, Scotland and Cumbria had low proportions of Continental gulls, while the highest proportions occurred in south Wales, southern England, and eastern England from Yorkshire southwards. Overall, about 71 per cent of the wintering gulls in Britain and Ireland originated from the Continent – a high value, but consistent with the much higher overall numbers of Black-headed Gulls reported here compared with estimates in the breeding season.

FIG 33. Estimates of the percentage of Continental Black-headed Gulls present in 10 regions of Britain and Ireland in winter based on numbers of recoveries of British and Continental ringed birds in each region between early December and the end of February.

Sex ratio of wintering birds

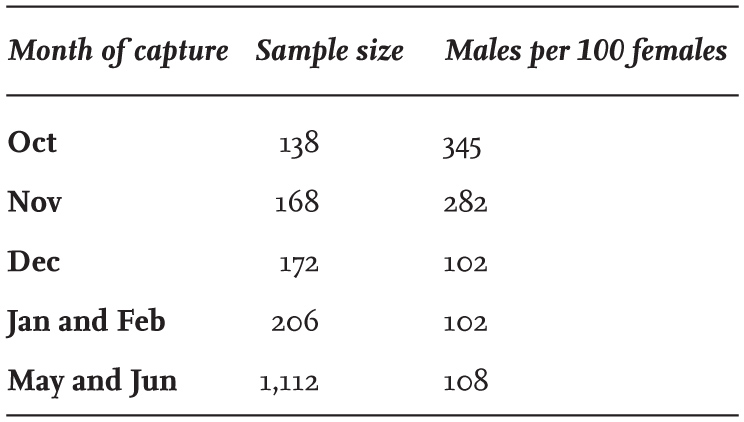

While the sex ratio of Herring Gulls and Great Black-backed Gulls (Larus marinus) captured in Britain during the winter approaches equality, that of wintering Black-headed Gulls shows a marked skew, with many more males being present. The data in Table 13 show that birds identified at breeding sites in northern England in May and June contained a minor excess of 108 males per 100 females. However, the sex ratio of wintering birds captured in England changed considerably, with a threefold excess of males in October and November, followed by the reversion of proportions to near equality between December to February. In the winter samples, most individuals were visitors from the Continent, and the skewed sex ratio in October and November suggests that either migrating males were arriving earlier than the females by an average of a month or more, or that males and females were feeding at different types of sites not sampled in those months, but were feeding at the same sites later in the winter. A total of 20 males and 11 females wing-tagged in the autumn were subsequently reported to have returned to the Continent, which gives some support for the suggestion that the bimodal pattern of the arrival time of Continental gulls (Fig. 32) represents males migrating earlier than females.

TABLE 13. The sex ratio of adult Black-headed Gulls cannon netted at landfill sites between October and February in north-east England, and near large colonies in northern England in May and June. Males were identified by a head and bill measurement of 82 mm or longer.

BREEDING BIOLOGY

Black-headed Gulls build their nest on the ground in areas with low-growing vegetation of varying density, ranging from sand dunes with much bare ground, to taller and floating vegetation around tarns and lakes. However, a few exceptions have been reported. At Seamew Crag, a small islet on Lake Windermere, Clive Hartley and Robin Sellers recorded several of the 50 pairs in the colony there nesting on top of low bushes over several years following 2009 (pers. comm.). In East Anglia in 1947, an entire colony numbering more than 300 pairs switched to nesting 2–3 m above ground level in young spruce trees, apparently in response to the flooding of their usual nest sites on the ground (Vine & Sergeant, 1948). Unlike some other gull species, there is only one old record of Black-headed Gulls nesting on a building, but in 2015 Robin Sellers found three small groups doing so, two near Perth and the other at Montrose, both in Scotland (pers. comm.).

Philopatry and colony faithfulness

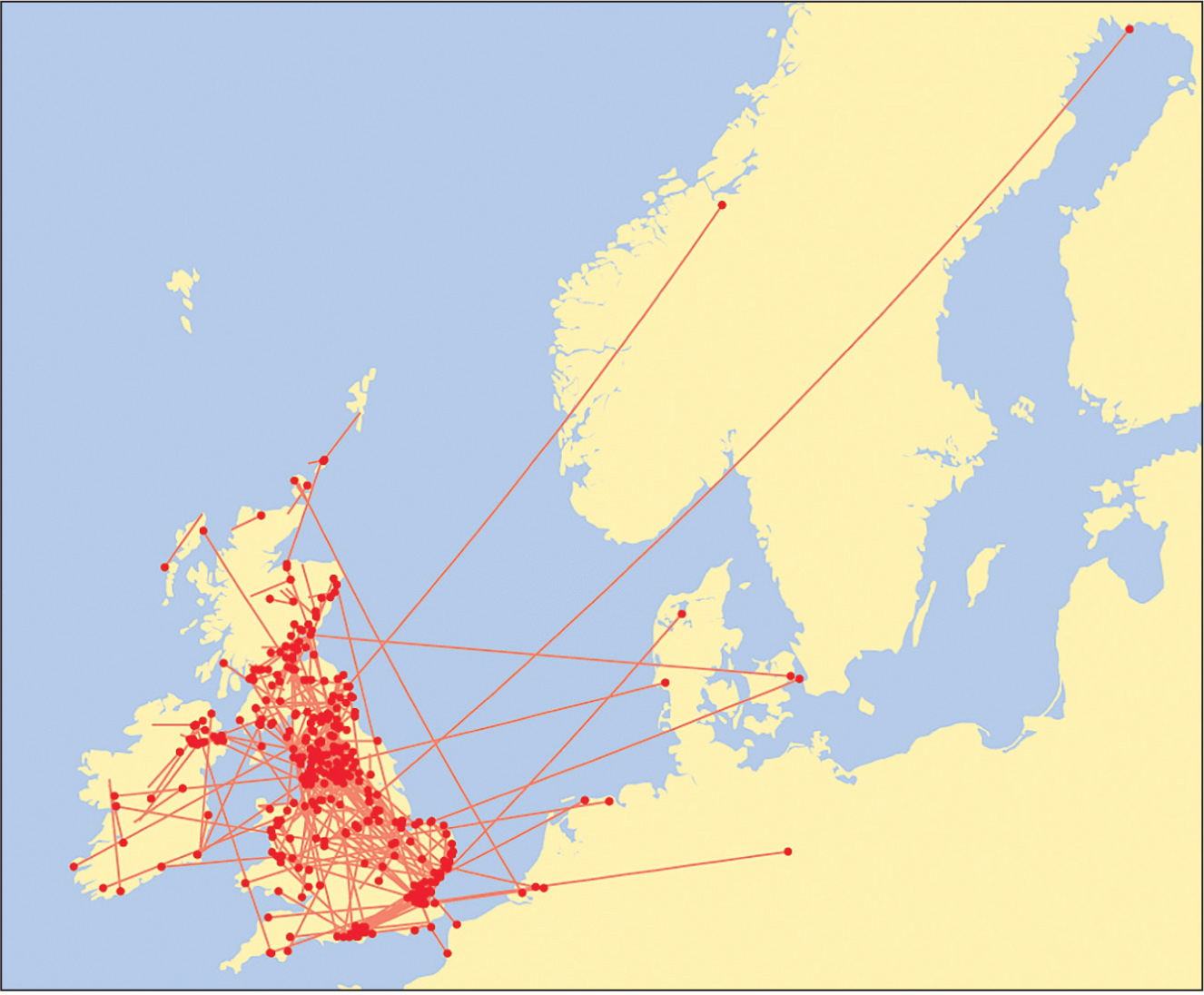

Most Black-headed Gulls are two years old before they breed for the first time and a minority are a year older before they breed. Exceptionally, one-year-old individuals attempt to breed, although their success is very low. Many of those that have survived to maturity return to breed in the colony in which they hatched as chicks (called philopatry), but others move to other colonies, often some distance away. The high proportion returning to the natal colony indicates that the young birds retain a good memory of where they were reared. However, it is easier to find marked individuals that have returned to their original colony than those that have moved elsewhere and consequently the extent of philopatry is often exaggerated. A realistic estimate of the extent of philopatry is obtained by measuring the proportion of those ringed as chicks and have reached adult age that were recovered during the breeding season less than 20 km from their natal site. In the case of the Black-headed Gull, about 60 per cent of the young that survive to breeding age are philopatric and the remaining 40 per cent move to other colonies and in a few cases, across the North Sea, to breed on the Continent. There have also been exchanges of individuals between Ireland and Britain (Fig. 34). Once adults have bred in a colony, their attachment to it becomes high, and at least 85 per cent of those surviving to the following year return to it to breed. The few adults that move elsewhere to breed are mainly from colonies that are in the process of being deserted, in some cases as a reaction to repeated nesting failure and the presence of mammalian predators.

FIG 34. Movements of more than 20 km of Black-headed Gulls ringed as chicks in Britain and Ireland and recovered in the breeding season when of breeding age. Many returned to breed at or near where they were reared, but a similar proportion apparently moved to other colonies. A few moved to the Continent to breed, mainly between northern France and Denmark, but one moved to Germany, another to Norway and a third to northern Sweden. Reproduced from The Migration Atlas (Wernham et al. 2002), with permission from the BTO.

Annual reoccupation of the colony

Black-headed Gull colonies are first visited by groups of adults in March each year. They arrive at irregular intervals during the morning, flying over the site without landing, and do not remain long at the colony or in the vicinity. Eventually, on one such visit some birds do land, but they exhibit a degree of nervousness and are easily disturbed. These visits become more frequent, but will be curtailed or prevented by cold and windy weather. As the days pass, the daily presence of the birds at the colony lasts much longer and spreads into the afternoon, but the colony is always vacated before sunset. The gulls usually leave by a synchronous ‘up’ or ‘panic’ flight, which sees them all suddenly rising high above the colony as if alarmed, yet without an obvious stimulus such as the appearance of a predator. As April progress, the amount of time the gulls spend at potential nest sites extends to the greater part of the day, but the colony is still deserted each night and reoccupied early in the morning, sometimes well before sunrise.

Pairs are formed early and courtship displays become common (Fig. 35). In the meantime, nesting material is collected locally and brought in to the colony. Birds nesting in some coastal colonies often collect substantial and untidy quantities of brown seaweed, while those at inland sites collect dry grass locally and carry it to the selected nest site to construct the nest. More material is usually added to the nest during incubation. Colonies and nesting sites are usually close to water, and nests are often substantial structures that raise the eggs above the local water levels.

FIG 35. Female Black-headed Gull (right) courtship-begging for food from a male. (Norman Deans van Swelm)

The density of nests varies according to the size of the colony and the nature of the nesting site. Nests are 1–2 m or more apart where plant growth is sparse, but only 50 cm apart in dense vegetation, presumably because this tends to conceal the neighbouring pair, moderating the extent of aggression between close neighbours.

Eggs and incubation

Black-headed Gull eggs are brown with spots of a darker colour. They are laid in mid- to late April (the date of the first egg laid in different years at Ravenglass ranged between 12 April and 26 April), but even at this time the colony is still often deserted at night, with the adults moving to night roosts and leaving the early eggs unprotected. As clutches are completed and incubation begins, increasing numbers of birds remain in the colony throughout the night; it is at this point that predation by Foxes on incubating adults may occur.

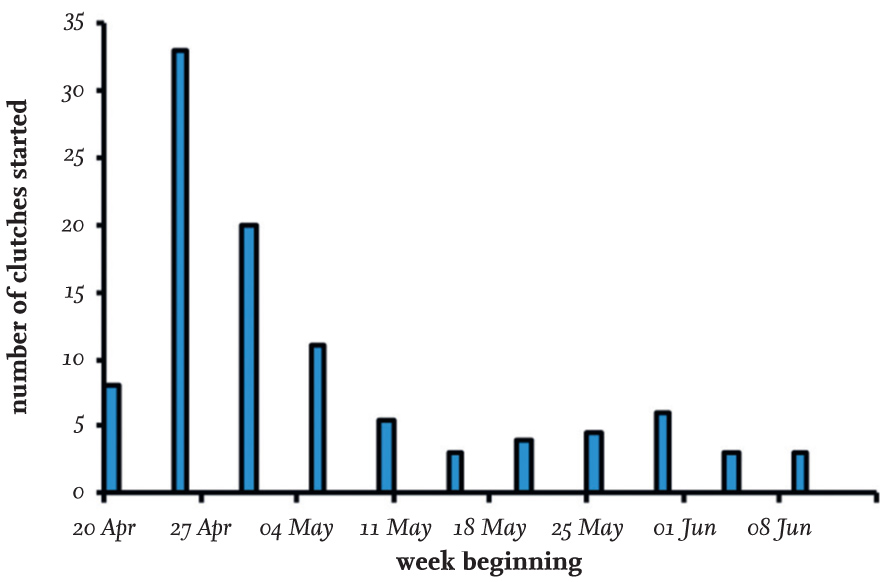

In Britain, the peak of laying in Black-headed Gulls is reached at the end of April or in early May, which is earlier than in other gull species breeding here. Fig. 36 shows the date distribution for the first eggs in each clutch recorded by Ian Patterson at Ravenglass (1965). There is considerable laying synchrony by the majority of pairs, but there is often a distinct tail or a secondary late peak of birds that re-lay after losing their first clutch or delay laying owing to inexperience.

The typical clutch comprises three eggs, although two-egg clutches are common. Occasionally, four-egg clutches occur, but whether these are laid by only one female has not been investigated. Late-laying birds produce clutches of just one or two eggs. Average clutch size within a colony varies considerably, from 2.3 to 2.8 eggs. Nils Ytreberg (1956) recorded a high average of 2.9 eggs from 411 nests in Norway, but in a later year reported a smaller average of 2.62 eggs based on a sample of 100 nests (Ytreberg 1960). The average clutch size tends to be lower in years when laying starts late, such as in small colonies and those further north and in the uplands. Eggs are laid at variable times throughout the day and the interval between eggs is usually about two days.

FIG 36. The spread of the laying season at Ravenglass, recorded by Ian Patterson in 1965. The secondary peak at the end of May/early June probably comprised repeat clutches produced by pairs that had lost their first clutch or by pairs of young, inexperienced birds.

Incubation of eggs and feeding of young is shared by both members of the pair. The eggs are covered by an adult irregularly while the clutch is still being laid, with the first egg probably protected rather than incubated. Obviously, incubation does not take place at night on occasions when the adults desert the colony in the evening. Intensive incubation starts at variable stages during laying of the clutch and often before the third egg is laid, but the brood patches of incubating birds are not fully vascularised for the first few days and initially the covered eggs may not reach a high enough temperature to facilitate development. This results in variable incubation periods, and the early start of incubation is sometimes enough to cause the third egg to hatch a day or so after the first two. Ivan Goodbody (1955) recorded incubation periods from the laying of the last egg of between 23 and 26 days at different nests.

Rearing young

A study by Roland Brandl and Ingrid Nelsen (1988) reported that Black-headed Gulls feed their chicks at intervals of about 45 minutes during daylight (but not at night), and that chicks receive at least 20 feeds each day. Each parent made five to six feeding trips per day, and obviously retained food from each trip for at least two feeding bouts. The authors found that this rate was mainly independent of the nestlings’ age or brood size. Adults regurgitate food onto the ground for the chicks and often re-swallow any surplus.

The newly hatched young have cryptically marked down, and as they grow, the feathers are patterned in shades of brown. The chicks remain in the nest for about a week if undisturbed and are brooded by their parents for a decreasing length of time each day as they grow older. Brooding at night often continues for a day or two longer after daytime brooding has ceased. Chicks eventually move a short distance away from the nest and shelter in nearby vegetation, where they receive some protection from both adverse weather and predators. One parent remains at the nest site most of the time, feeding the chicks by regurgitation and defending them against neighbouring adults and attacking wandering young from other pairs.

Once chicks reach 20 days old, they develop an interest in searching the ground for items they can pick up and swallow. Although they probably find little that is edible this way, the behaviour seems to develop their ability to search for food. Young birds can fly when they are about 34 days old and leave the colony area soon after fledging, often accumulating in small groups in open areas nearby. There, they search for food, later joining feeding flocks of adults in fields or on the shore. There is no evidence that the young are accompanied or fed by their parents once they leave the colony, nor do they return to the nest site to be fed after their first flight.

Breeding success

Breeding success in Black-headed Gulls is highly variable and depends on whether the colony is protected from predators, including humans. American Mink, rats, Badgers (Meles meles), hedgehogs, Foxes and herons are major predators at some sites, and are suspected to have caused the desertion of several colonies. Intensive predation can result in very few young fledging from a colony. For example, in a sample area at Ravenglass studied in detail by Ian Patterson, 2,213 pairs each fledged an average of only 0.06 young in 1961, while in 1963, 2,290 pairs each fledged an average of 0.10 chicks (Patterson, 1965). This poor breeding success was mainly caused by Fox predation on eggs, young and adults late in the breeding season.

At colonies where predation has been typically much lower than at Ravenglass, Black-headed Gulls probably fledge about 0.6–0.7 young per pair each breeding season. On its website, JNCC reports an average production of about 0.6 young per pair annually based on a few sample colonies studied between 1987 and 2015, but in the best year 1.2 chicks per pair fledged. Studies of several colonies over many years in France reported an average of 1.4 young fledged per pair (Péron et al., 2009). Once the last few young fledge, which is usually in late July or early August, colonies are rapidly deserted until the next breeding season.