Полная версия:

Gulls

VOICE

Most gulls are vocal, particularly in the breeding season, and this plays a part in their breeding behaviour. Calls are usually harsh and loud, and are used in territorial defence, as an alarm when birds are disturbed by predators or in greeting a mate. Quieter calls are used during courtship, and specific calls are also uttered, such as the wack-wack call of the Kittiwake during breeding, which tells its mate that it is not moving locally but is leaving and will be away some time on a feeding trip. Other specific calls are used during copulation, to maintain contact in flocks in flight, and to indicate that a food source has been found and that the calling individual is about to feed.

Studies using sonographs to analyse calls for several gull species have shown that there is a wide range of variation in the same call made by different individuals. Playbacks of the calls indicate that birds can recognise the call of their own mate but fail to respond to the same call when it is made by other individuals, suggesting that voice plays a part in individual recognition in addition to visual cues. Chicks of many gull species are able to recognise their parents at a relatively young age, and likewise the parents can identify their own chicks, apparently by their calls and actions – they respond differently to strange individuals. This is particularly important in species where the young wander or group together in a crèche. The Kittiwake is the exception in that adults appear to be unable to recognise their own chicks, although the usual isolated position of the nest on a vertical cliff face forces most chicks to remain in the same nest until they fledge. Occasionally, when two nests are built side by side, a Kittiwake chick will move across to the neighbouring nest and join chicks already there. If the wandering chick is placed back in its own nest, it soon returns to the neighbouring nest again, but such moves seem to be accepted by both pairs of adults.

ROOSTING

Gulls are inactive in the darkness of the night, spending these hours passively, although some species feed locally where there is strong artificial illumination, such as around working trawlers and in town centres. Most gull species spend the night in large flocks, with many roosting on water in sheltered bays at the coast, on reservoirs and on lakes, or on land in places that are free of predators, such as small islands.

Gull roosts are composed of single or mixed species, and may number thousands of individuals. Roost sites are often used year after year if their position excludes mammalian predators. Most species avoid roosting on water exposed to severe wave action, presumably because they do not possess the behavioural adaptations needed to cope with resting and sleeping while sitting on rough or breaking water. Sabine’s Gull, Ross’s Gull and the Kittiwake are totally oceanic outside the breeding season and are the only gulls that regularly spend the night far from shore. Kittiwakes will also roost offshore during the breeding season if they are not incubating or protecting small young in the nest. Before egg-laying, they leave the colony at, or long after, sunset and fly many kilometres out to sea in the dark.

CHAPTER 2

Black-headed Gull

APPEARANCE

The Black-headed Gull (Chroicocephalus ridibundus) is a small gull with a wingspan of about 85 cm. It is common both on coasts and inland, and while it is less abundant than the Kittiwake (Rissa tridactyla), it is much more familiar to the public thanks to its dark head in summer (Fig. 15, left), which gives rise to its common name. The hood is actually dark brown, not black, and while the eye is also dark, the white semicircle around the back of it draws attention to it when the bird is seen at close range. The species is frequently attracted to food in towns and even large cities, both inland and on the coast, but for more than half of the year adults lack the dark hood and are more difficult to identify. At that time, the white head has only small, dark grey patches behind the eyes, but the red bill and legs, and the light leading edge to the wing when in flight, aid recognition (Fig. 15, right). The sexes are similar, with the male being only slightly larger than the female.

FIG 15. Adult Black-headed Gull in summer plumage (left) and winter plumage (right). (Left, Alan Dean, right, Nicholas Aebischer)

Juveniles differ markedly from the adults. They have brown feathers on the wings, on the back of the neck and on top of the head, and these form part of a cryptic patterning that helps to conceal them in vegetation before they fledge. During the first year of life, they lack the bright red legs and bill of the adults, and, although present, the white outer edges to the wings are less obvious. First-years have a black band to the tail, but as this is also present in several other species of small gulls in their first year of life, it is a useful characteristic to age but not to species identification. In the first summer after hatching, the immature birds develop a dark hood later than the adults; this is usually incomplete and mixed with some white feathers. They also retain most of the dark band to the tail. Following the autumn moult, immature individuals entering their second year of life assume the adult plumage, including an all-white tail, but many still have less intensely red legs at this stage.

DISTRIBUTION AND HABITATS

The Black-headed Gull is widely distributed in Europe and breeds across Asia, and there is no evidence of subspecies within this large range. The species extended its western range in the twentieth century, reaching the Faeroes early on at an unrecorded date, Iceland in 1910 (50,000 adults now breed there) and Greenland in 1969. Breeding in North America was suspected as early as 1963 but not proven until 1977, when nesting by 14 pairs was recorded in Newfoundland. More recently, breeding has been suspected at other sites in North America, with recently fledged young being reported at several locations from Labrador to Massachusetts. Several young birds ringed in Iceland have been recovered during winter in Newfoundland and Labrador, but only one ringed individual of this species is known to have crossed from the mainland of Europe to the New World. It was ringed in the Netherlands and recovered 200 km off the coast of Labrador, so it seems likely that those seen in North America are mainly individuals reared in Greenland and Iceland.

Movement to North America has progressed in a series of stages rather by a sudden irruptive transatlantic movement from Europe, with birds breeding or reared in the Faeroes, Iceland and Greenland gradually moving west. This spread, together with a northern movement in Norway, Sweden and Finland, has been interpreted as a response to climate change. However, this theory ignores the spread of breeding to Italy (1960) and Spain (1960), and the fact that the increase within the species’ core area in Europe during the twentieth century has probably been mainly responsible for the spread of the western limits of its breeding distribution.

Today, unknown numbers of Black-headed Gulls nest across Asia and some 4 million to 5 million adults breed in Europe, of which about 250,000 nest in Britain and Ireland. Those breeding here probably represent less than 5 per cent percent of the world population.

The Black-headed Gull is the commonest gull frequenting sports fields, landfill sites, harbours and areas around large shopping complexes, and the birds also seek food in urban streets, domestic gardens and even at bird tables during severe winter weather. In many areas, they are also the gull most likely to be seen following the plough in agricultural fields. The species achieved fame in literature as the character Kehaar in the well-known book Watership Down, written by Richard Adams (1972). Kehaar suffered a damaged wing and took refuge at Watership Down, eventually recovering and returning to his colony.

Numbers of Black-headed Gulls in and around towns and cities can be high, particularly in winter, but this has not always been the case. For example, until the end of the nineteenth century the species was considered scarce in central London, but the birds are now present here in their thousands in winter, where they are abundant in parks, sports fields, lakes and the river Thames, often seen competing vigorously for scraps of food.

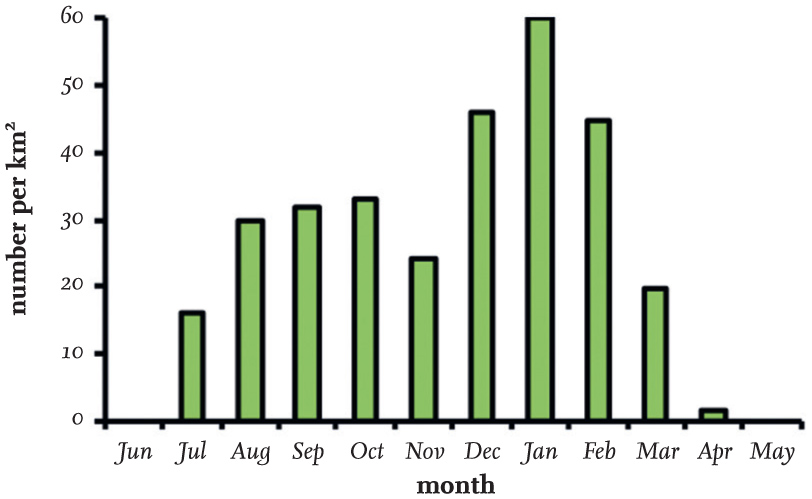

The gathering of flocks of Black-headed Gulls around towns and cities varies through the year. Fig. 16 shows their density month by month within a radius of 5 km of Durham, where many were recorded on sports fields, pastures and the river Wear running through the city centre, or patrolling streets and shopping centres in search of discarded food. The gulls retreated to their colonies in March, and since none of these was within 40 km of the city, only an occasional immature bird was recorded in April and none of any age in May and June. There are many accounts of Black-headed Gulls frequenting other areas in winter and being absent there in spring and summer. It is obvious that the distribution of the birds in Britain becomes much more clumped during the breeding season and is limited by feeding range from colonies. At most colonies, first-year (non-breeding) Black-headed Gulls are also infrequent and those that are encountered are seen feeding with adults well away from colonies, commonly on intertidal estuaries.

FIG 16. The seasonal variation in the numbers of Black-headed Gulls within a radius of 5 km of the city of Durham between 1982 and 1984, and in the absence of local breeding colonies. In each year, the gulls were absent in May and June, and the first individuals arrived in July, coinciding with the Durham Miners’ Gala, when a considerable amount of food was dropped by the large numbers of people attending the event. Based on data collected by MacKinnon (1986).

HISTORICAL BREEDING STATUS IN BRITAIN AND IRELAND

The status of the Black-headed Gull in Britain and Ireland in or before the twentieth century is not clear owing to a lack of detailed information. On its website, the British Trust for Ornithology (www.bto.org) says that the species was a rare breeding bird in Britain in the nineteenth century, and the statement made by John Gurney Jr in 1919 that the species was in danger of extinction here cannot be true. Both opinions lack supporting evidence and are contradicted by the extensive egg collecting that occurred at that time (here), and by the historical evidence accumulated by Michael Shrubb in his book Feasting, Fowling and Feathers – a History of the Exploitation of Wild Birds (2013). It is likely that the movement of colonies was misinterpreted as a decline in numbers, and that the ‘disappearances’ of the birds were probably movements of adults elsewhere and the establishment of new colonies in response to nest predation. Such movements of colonies are also frequent, and better known, in the Little Tern (Sternula albifrons), where they are closely related to poor breeding success induced by predators or by human disturbance.

There can be little doubt that the numbers of Black-headed Gulls breeding in Britain increased in the period between 1900 and 1973, as did those of many other gull species breeding here. However, Black-headed Gulls are not easy to count accurately. Colonies of very varying sizes occur both on coasts and inland, and the latter are often particularly difficult to count, with nesting taking place in marshes, on islands in lakes and tarns, and sometimes among tall or floating vegetation in boggy areas. In addition, colonies on moorland are often small and scattered, and new ones can remain overlooked for some time.

The first census of Black-headed Gulls in England and Wales was made in 1938, with further surveys in 1958 and 1973. The report of the census made in 1973 concluded that there were between 200,000 and 220,000 breeding adults, and that since 1938 there had been an increase of 177 per cent, while the number of colonies containing more than 2,000 adults had doubled since 1958. However, part of the reported increase might be attributed to a better coverage of colonies in 1973. In Scotland, a census made in 1958 suggested that there had been little recent change in abundance, but that numbers had continued to be influenced by uncontrolled egg collecting. The national censuses of Britain and Ireland in 1970 and 1985 counted only coastal-nesting Black-headed Gulls and did not consider the appreciable numbers nesting inland. The census in 2000 included inland colonies for the first time and resulted in an estimate of about 336,000 breeding adults in Britain and Ireland, of which 44 per cent were nesting inland.

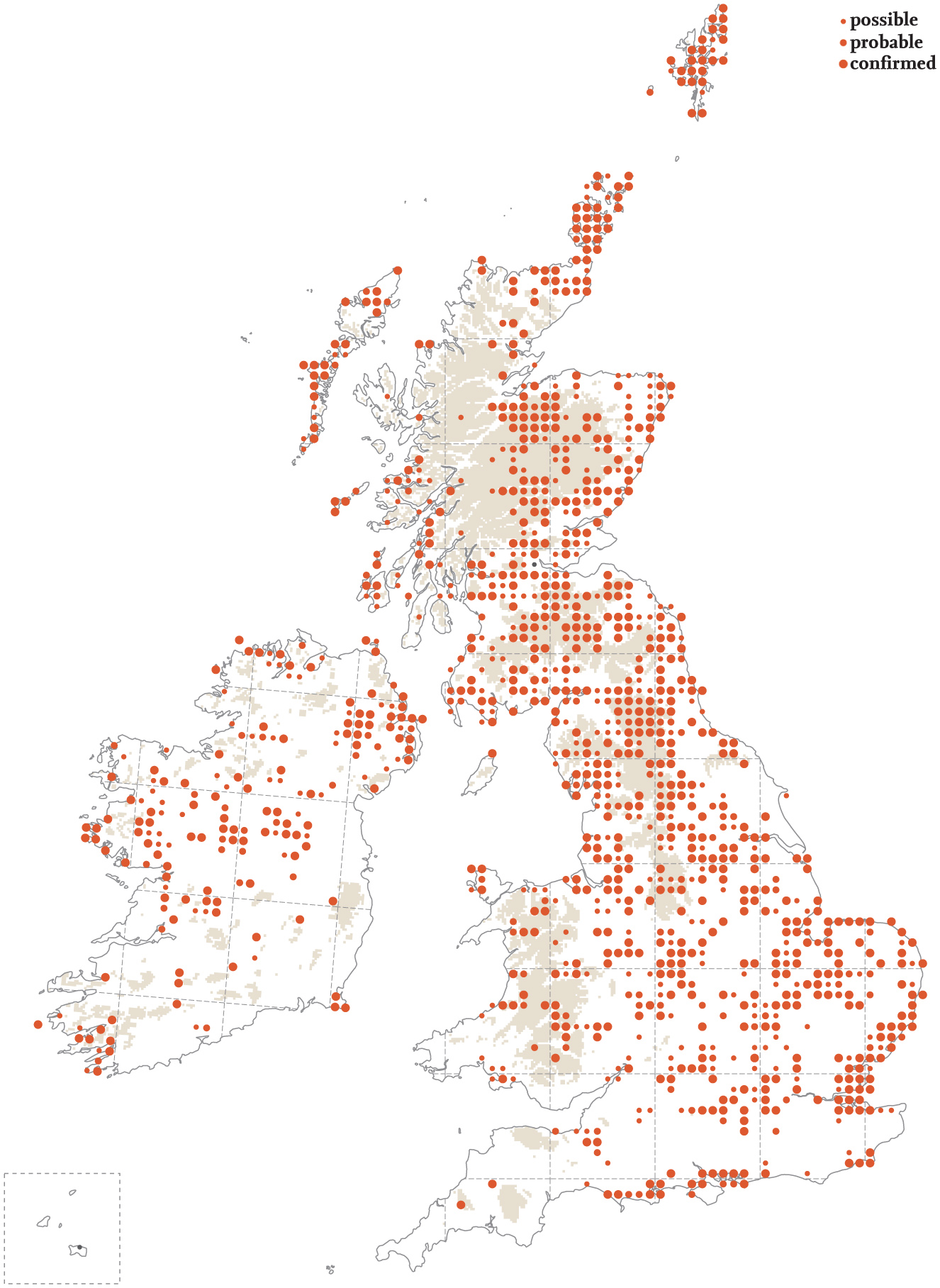

FIG 17. Map of the breeding distribution of the Black-headed Gull in Britain and Ireland in 2008–11. Reproduced from Bird Atlas 2007–11 (Balmer et al., 2013), which was a joint project between the British Trust for Ornithology, BirdWatch Ireland and the Scottish Ornithologists’ Club. Channel Islands are displaced to the bottom left corner. Map reproduced with permission from the British Trust for Ornithology.

Between 1970 and 1985, a 71 per cent decline in coastal-breeding Black-headed Gulls in the Republic of Ireland was reported, but the numbers there had recovered by the time of the 2000 census. It is possible that an appreciable proportion of the missing birds in 1985 had not, in fact, died, but had moved to new breeding sites not visited at that time.

The general impression from these censuses is that the numbers of breeding Black-headed Gulls in Britain and Ireland increased during most of the twentieth century, and then numbers showed little overall change in Britain between 1985 and 2000. The meagre and incomplete data available since then hints that numbers have been maintained.

The BTO Bird Atlas 2007–11 data, collected between 1968–72 and 2007–11, reported a reduction of 55 per cent in the number of 10 km squares in Britain and Ireland containing breeding Black-headed Gulls. Whether this reflects a decline in overall numbers is uncertain, as it could be the result of a trend towards fewer, larger colonies. Sample counts made at some coastal sites by the Joint Nature Conservation Committee (JNCC) show little evidence of a national change in numbers between 1986 and 2015, and this is supported by the national censuses in 1985 and 2000, which (although the earlier census was incomplete) did not suggest any major overall numerical changes within Britain and Ireland.

There has been a trend over time towards decreasing numbers of Black-headed Gulls breeding at inland sites, while numbers nesting at coastal sites have increased in England and Wales. However, this change does not seem to have occurred in Scotland. This movement probably reflects that birds breeding on coastal islands are often better protected from both humans and Foxes (Vulpes vulpes) than those breeding inland. The impact of the dramatic increase of Fox numbers in Britain in recent years is not frequently appreciated. Stephen Tapper (1992) found that numbers of this predator had increased fourfold between 1961 and 1990, and suggested that the effect of Fox predation on Black-headed Gull colonies may be greater and more widespread than that caused by American Mink (Neovison vison).

COLONIES

Colony sizes

The Black-headed Gull is a colonial breeder, nesting on a wide range of sites, including lakes, reservoirs, small moorland pools and tarns, marshes, sewage farms, clay pits, dunes, saltmarshes and industrial ponds. While numbers of nests in some colonies are easily counted, others are difficult to measure as the nests can be concealed by vegetation or lie on boggy ground, making access difficult or risking damage to the vegetation. Good vantage points do not exist near many colonies, and different methods are therefore needed here to estimate their size.

The basic unit used to measure the size of a colony is the number of nests, applying the realistic assumption that two adult birds are associated with each nest. In very large colonies, sampling of nest density has been used and then extrapolated across the total area of the colony as delineated from aerial photographs or detailed large-scale maps. At some sites, pair and hence nest numbers have been estimated through the less reliable method of counting numbers of birds in the air when disturbed and then using a conversion factor, such as dividing by 1.55. Most Black-headed Gull census counts have errors, which should be considered when making interpretations of the national status of the species and possible changes in abundance over time.

FIG 18. Part of the colony of Black-headed Gulls nesting with Sandwich Terns (Thalasseus sandvicensis) on Coquet Island, Northumberland. (John Coulson)

Data for years since 1980 on Black-headed Gull colony size recorded in the UK Seabird Colony Register allows for an in-depth assessment. While the species is essentially a colonial breeder, solitary breeding pairs on the day of counting comprised 10 per cent of the sites in Scotland and 8 per cent in England. Whether many of these pairs had been solitary for the entire breeding season is uncertain, because most of the nesting sites were visited by counters only once. It is possible that some single pairs were the sole remainders of a group present earlier in the breeding season that had suffered predation or disturbance, and had deserted the site prior to the observer’s visit. Single pairs of Black-headed Gulls can probably breed without the need of stimulus of other pairs, although when they do so, they nest late and their breeding success is usually low.

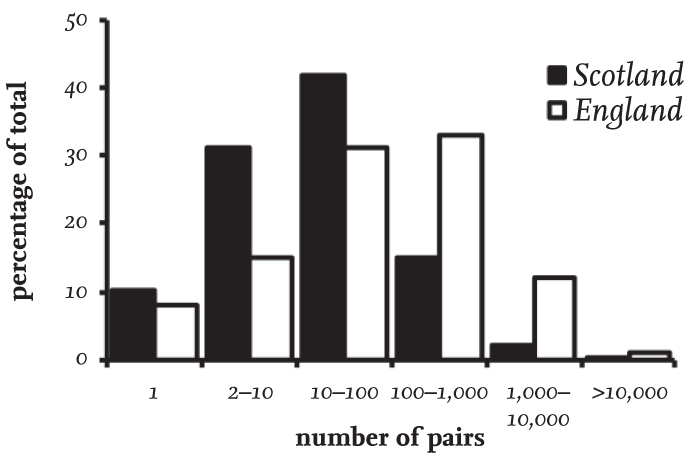

In Britain and Ireland, the numbers of pairs of Black-headed Gulls estimated at breeding sites (subsequently referred to as colonies for convenience, and including sites with single pairs) between 1980 and 2015 ranged from only one pair to more than 10,000 pairs. Overall, a third of colonies in Britain contained between 10 and 100 nesting pairs (Fig. 19).

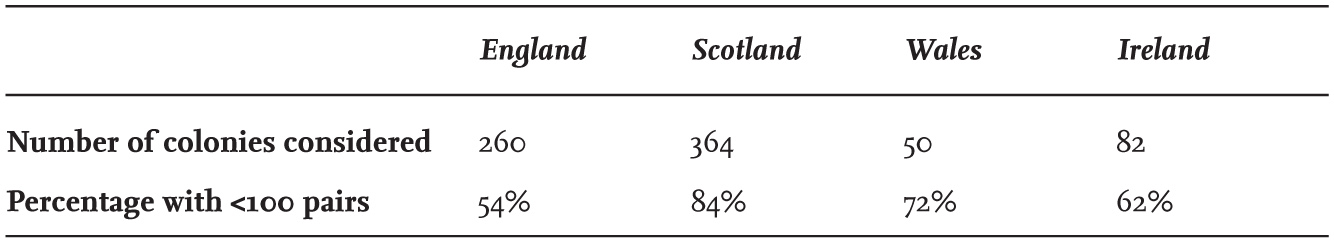

At the same time, the average size of colonies differed between Scotland and England, with 84 per cent in Scotland having fewer than 100 pairs (Table 8), while the comparable figure for England was a third lower, at 54 per cent. Colonies with 100 to 1,000 pairs were twice as frequent in England than in Scotland, while colonies of more than 1,000 pairs formed 13 per cent of all sites recorded in England, but only 2 per cent of those in Scotland.

These differences reflect the type of nesting sites used in the two regions, with the majority in Scotland being inland on upland sites and usually associated with relatively small waterbodies, while in England large coastal colonies were more frequent and were sometimes extremely large. The distributions of colony sizes in Wales and Ireland were intermediate between those in England and Scotland, with 72 per cent of colonies in Wales and 62 per cent in Ireland having fewer than 100 pairs (Table 8).

FIG 19. The size distribution of Black-headed Gull colonies (including sites with only one pair) in England and Scotland between 1980 and 2015, based on Seabird Colony Register data for 364 colonies surveyed in Scotland and 260 in England.

TABLE 8. The proportion of Black-headed Gull colonies in England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland with fewer than 100 breeding pairs, based on data from 1980–2015. Sites with a single pair present have been included.

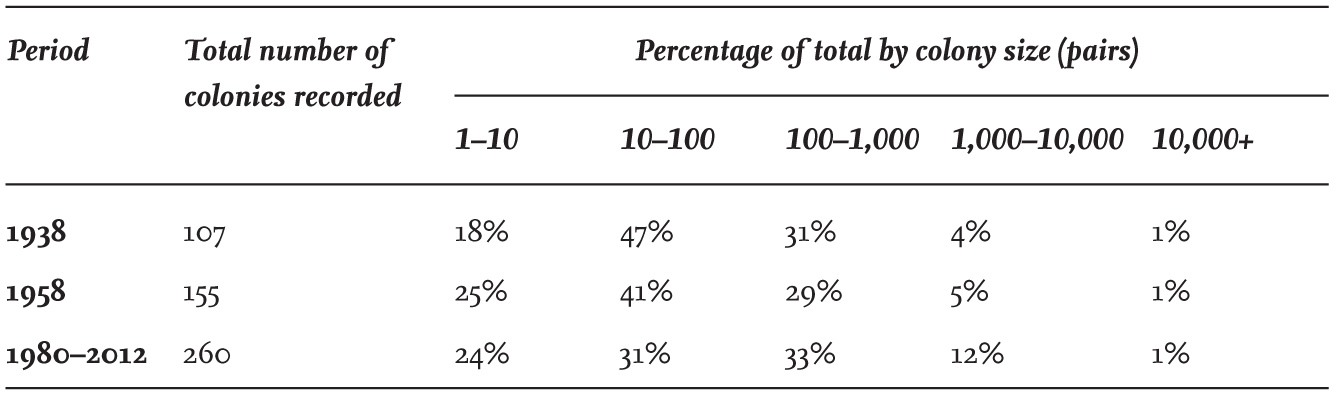

TABLE 9. The percentage of Black-headed Gull colonies of different sizes in England and Wales in 1938, 1958 and 1980–2012. Sites with only one pair are included.

A comparison between the size of colonies reported in the 1938 and 1958 censuses made in England and Wales, and more recent data collated in the Seabird Colony Register, show progressive changes in colony sizes over time (Table 9). There has been an overall decrease in the proportion of colonies with fewer than 100 pairs since 1958, while the proportion and total numbers of large colonies with more than 1,000 pairs has more than doubled over the same period. Many colonies – particularly small ones in England and Wales – have disappeared for various reasons, including disturbance, predation and drainage, while others – particularly large ones – are now protected within nature reserves, although even a few of these have disappeared.

Persistence of colonies

While some Black-headed Gull colonies persist for many years, in general they are not as permanent as those of the Kittiwake or Herring Gull (Larus argentatus). Over the past hundred years, many Black-headed Gull colonies have disappeared while new ones have become established. Small colonies are particularly susceptible to decline, and this is especially true of those on upland moors, where the birds nest around small bog pools, reservoirs and lakes. A consequence of this is that some of these mobile groups can be missed during census work.

Various reasons have been suggested for the desertion of colonies. In some cases these are speculative, and include drainage, military activity, competition from increasing numbers of large gulls, aggression by Mute Swans (Cygnus olor) and Canada Geese (Branta canadensis), egg collecting, keepering, and predation by Foxes and American Mink. Rats and Foxes have been a persistent problem for Black-headed Gulls nesting at Blakeney Point in Norfolk, and no young were reared at the colony in 2000. In 2014, Fox predation at the same site resulted in very few chicks being reared by the 2,200 pairs present, while in 2016 an appreciable increase of rats caused the gulls to abandon the colony and, presumably, move elsewhere.

Ravenglass colony

The site of the very large Black-headed Gull colony on the coast of Cumbria at Ravenglass is owned by the Muncaster Estate. There has been continuous collection of eggs there since the seventeenth century, a practice that was recorded as being extensive in 1886. Del Hoyt has suggested the colony had an annual yield of 30,000 eggs over many years. Neither Michael Shrubb’s searches (2013) nor my own have uncovered documentation to confirm or contradict this statement, but the colony was certainly used consistently as a source of freshly laid eggs for much of the twentieth century by the estate, and workers also took some young from time to time. The collection of eggs was well organised and was stopped each year on an agreed date, which left time for successful breeding by birds laying late or with repeated clutches. David Bannerman recorded that the estate collected 72,398 eggs at Ravenglass in 1941 and 24,568 in 1951, when a further 6,000 eggs were taken (presumably illegally) by others.

In 1954, the site was leased to Cumberland County Council as a local nature reserve and egg collecting ceased. The gulls were protected and studied in the ensuing decade by Niko Tinbergen’s research group from Oxford University. During the period 1954–68, the colony size remained between 8,000 and 12,000 pairs, but during this time predation on eggs, chicks and adults occurred from time to time and breeding success was low. In 1968, a full-time warden was appointed, and he reported that 8,100 pairs nested. From then onwards, a marked decline continued each year; Neil Anderson’s study in 1984 found only 1,300 pairs nesting, and the colony was totally deserted in 1985 (Anderson, 1990). Five pairs nested there in 1988 and three pairs in 1989, but none since (Fig. 20). Predation by mammals over several years, particularly Foxes, was thought to be the cause of decline and ultimate desertion. The abandonment of the Ravenglass colony probably involved a movement of Black-headed Gulls to several other colonies, possibly those in the Ribble Estuary and Sunbiggin Tarn, because no new or established colonies were nearer.